Not All Were Created Equal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ancient Sparta Was a Warrior Society in Ancient Greece That Reached

Ancient Sparta was a warrior society in ancient Greece that reached the height of its power after defeating rival city-state Athens in the Peloponnesian War (431-404 B.C.). Spartan culture was centered on loyalty to the state and military service. At age 7, Spartan boys entered a rigorous state-sponsored education, military training and socialization program. Known as the Agoge, the system emphasized duty, discipline and endurance. Although Spartan women were not active in the military, they were educated and enjoyed more status and freedom than other Greek women. Because Spartan men were professional soldiers, all manual labor was done by a slave class, the Helots. Despite their military prowess, the Spartans’ dominance was short-lived: In 371 B.C., they were defeated by Thebes at the Battle of Leuctra, and their empire went into a long period of decline. SPARTAN SOCIETY Sparta was an ancient Greek city-state located primarily in the present-day region of southern Greece called Laconia. The population of Sparta consisted of three main groups: the Spartans who were full citizens; the Helots, or serfs/slaves; and the Perioeci, who were neither slaves nor citizens. The Perioeci, whose name means “dwellers-around,” worked as craftsmen and traders, and built weapons for the Spartans. 3 Layers of ‘Social Stratification’ ← Top Tier: Spartan Male Warriors and Spartan Women ← Middle Tier: Non Warriors, not full citizens, considered to be outside of true Spartan society. These were artisans and merchants who made weapons and did business with the Spartans. (Perioeci) ← Helots or slaves. These were people who were conquered by the Spartans. -

The Effects of Mythos' on Plato's Educational Approach

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Elsevier - Publisher Connector Available online at www.sciencedirect.com Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences 55 ( 2012 ) 560 – 567 INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON NEW HORIZONS IN EDUCATION INTE2012 The Effects of Mythos’ on Plato's Educational Approach Derya Çığır Dikyola aIstanbul University Hasan Ali Yucel Education Faculty, Department of Social Science, Istanbul, Turkey. Abstract The purpose of this study, by examining the findings related to education in Greek mythos, is to reveal Plato's contributions to the educational approach. The similarities and differences between Plato’s educational approach and the education in Mythos are emphasized in this historical - comparison based study. The effect of mythos, which in fact give ideal education of the period, with the expressions they made about Gods’ and heroes’ education, on the educational approach of Plato, known to be intensely against the mythos, is rather surprising. ©© 20122012 Published Published by byElsevier Elsevier Ltd. SelectionLtd. Selection and/or peer-reviewand/or peer-review under responsibility under responsibility of The Association of The of Association Science, of EducationScience, Educationand Technology and TechnologyOpen access under CC BY-NC-ND license. Keywords: educational approach, educational history, mythology. 1. Introduction Plato is the first thinker of philosophy as well as of education. His ideas about education still have influence on schooling. Thus; Plato is a decent starting point in the studies over the meaning and the philosophy of education. Thinkers like Aristoteles, John Locke, J. J. Rousseau, and John Dewey, who produced education theories couldn’t help challenging Plato. -

Euboea and Athens

Euboea and Athens Proceedings of a Colloquium in Memory of Malcolm B. Wallace Athens 26-27 June 2009 2011 Publications of the Canadian Institute in Greece Publications de l’Institut canadien en Grèce No. 6 © The Canadian Institute in Greece / L’Institut canadien en Grèce 2011 Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication Euboea and Athens Colloquium in Memory of Malcolm B. Wallace (2009 : Athens, Greece) Euboea and Athens : proceedings of a colloquium in memory of Malcolm B. Wallace : Athens 26-27 June 2009 / David W. Rupp and Jonathan E. Tomlinson, editors. (Publications of the Canadian Institute in Greece = Publications de l'Institut canadien en Grèce ; no. 6) Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 978-0-9737979-1-6 1. Euboea Island (Greece)--Antiquities. 2. Euboea Island (Greece)--Civilization. 3. Euboea Island (Greece)--History. 4. Athens (Greece)--Antiquities. 5. Athens (Greece)--Civilization. 6. Athens (Greece)--History. I. Wallace, Malcolm B. (Malcolm Barton), 1942-2008 II. Rupp, David W. (David William), 1944- III. Tomlinson, Jonathan E. (Jonathan Edward), 1967- IV. Canadian Institute in Greece V. Title. VI. Series: Publications of the Canadian Institute in Greece ; no. 6. DF261.E9E93 2011 938 C2011-903495-6 The Canadian Institute in Greece Dionysiou Aiginitou 7 GR-115 28 Athens, Greece www.cig-icg.gr THOMAS G. PALAIMA Euboea, Athens, Thebes and Kadmos: The Implications of the Linear B References 1 The Linear B documents contain a good number of references to Thebes, and theories about the status of Thebes among Mycenaean centers have been prominent in Mycenological scholarship over the last twenty years.2 Assumptions about the hegemony of Thebes in the Mycenaean palatial period, whether just in central Greece or over a still wider area, are used as the starting point for interpreting references to: a) Athens: There is only one reference to Athens on a possibly early tablet (Knossos V 52) as a toponym a-ta-na = Ἀθήνη in the singular, as in Hom. -

A Brief History of Classical Education

A Brief History of Classical Lesson 4: The History of Ancient Education Education Dr. Matthew Post Outline: Ancient Education and Its Questions Ancient Education is all about character formation. The question is “What sort of character?” What are the morals towards which to form students? Scholé presents another issue. Ancients had less time to devote to proper scholé. The presence of corporeal punishment was questioned by many because it seemed to treat students as slaves (coercing them to do their work through physical pain). The “intellectual life” caused controversy because it often raised questions that unsettled the normal order. (i.e. Cicero held that the ideas of the Stoics made people complacent in the face of evil and some held that Plato’s ideas inspired people to go and assassinate the ruler of their town) Roman Education Three outcomes: Philosopher, Statesman, and Soldier Discussion of Liberal Arts originates in Rome especially with Cicero (without formalization of Medieval period) Education connected to the idea of pietas (from which we get the English words “piety” and “pity”). Pietas does not mean “piety,” it means “loyalty.” o Pietas is loyalty to one’s family, people, city, and the gods. Loyalty to the gods is what the English notion of piety refers to, but pietas encompasses more. Traditional Roman education is dictated by the paterfamilias (the head of the family – a father with power over all and everything in the family). “Aeneas & Anchises” by Pierre Lepautre (a famous show of pietas) o The paterfamilias often educated the children himself. (Famously Cato the Elder educated his children.) Education in the Roman family was for both men and women though they were educated differently. -

Ancient Sparta Ancient Athens

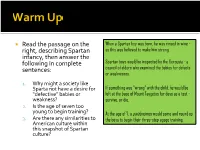

Read the passage on the When a Spartan boy was born, he was rinsed in wine - right, describing Spartan as this was believed to make him strong. infancy, then answer the following in complete Spartan boys would be inspected by the Gerousia - a sentences: council of elders who examined the babies for defects or weaknesses. 1. Why might a society like Sparta not have a desire for If something was “wrong” with the child, he would be “defective” babies or left at the base of Mount Taygetus for days as a test - weakness? survive, or die. 2. Is the age of seven too young to begin training? At the age of 7, a paidonómos would come and round up 3. Are there any similarities to the boys to begin their three-step agoge training. American culture within this snapshot of Spartan culture? Title: Comparative Study; Eastern Bloc and Worldly Civilizations Date: Know: I will be able to identify, describe, and analyze the similarities and differences of political involvement in livelihood across millennia. Relevance: Today we are learning about this because it is imperative to build knowledge in a pragmatic way – understanding that the real world and real life are connected to history is very important. Coming to this understanding is powerful! Do: I will write and discuss comparative issues between Ancient Greek city-states Do: I will write and discuss comparative issues between Medieval nations Do: I will write and discuss comparative issues between modern countries Write down the Essential Question: EQ: which child-rearing system had the greatest impact on population regulation? Warm Up Cornell Notes . -

VALOUR, DUTY, SACRIFICE: SPARTA ‘In Sparta Are to Be Found Those Who Are Most Enslaved and Those Who Are the Most Free.’

CHAPTER 2 VALOUR, DUTY, SACRIFICE: SPARTA ‘In Sparta are to be found those who are most enslaved and those who are the most free.’ CRITIAS OF ATHENS sample pages Spartan infantry in a formation called a phalanx. 38 39 CHAPTER 2 VALOUR, DUTY, SACRIFICE: SPARTA KEY POINTS KEY CONCEPTS OVERVIEW • At the end of the Dark Age, the Spartan polis emerged DEMOCRACY OLIGARCHY TYRANNY MONARCHY from the union of a few small villages in the Eurotas valley. Power vested in the hands Power vested in the hands A system under the control A system under the control • Owing to a shortage of land for its citizens, Sparta waged of all citizens of the polis of a few individuals of a non-hereditary ruler of a king war on its neighbour Messenia to expand its territory. unrestricted by any laws • The suppression of the Messenians led to a volatile slave or constitution population that threatened Sparta’s way of life, making the DEFINITION need for reform urgent. KEY EVENTS • A new constitution was put in place to ensure Sparta could protect itself from this new threat, as well as from tyranny. Citizens of the polis all A small, powerful and One individual exercises Hereditary rule passing 800 BCE • Sweeping reforms were made that transformed Sparta share equal rights in the wealthy aristocratic class complete authority over from father to son political sphere all aspects of everyday life Sparta emerges from the into a powerful military state that soon came to dominate Most citizens barred from Family dynasties claim without constraint Greek Dark Age the Peloponnese. -

University College London Department of Mtcient History a Thesis

MYCENAEAN AND NEAR EASTERN ECONOMIC ARCHIVES by ALEXMDER 1JCHITEL University College london Department of Mtcient History A thesis submitted in accordance with regulations for degree of Doctor of Phi]osophy in the University of London 1985 Moe uaepz Paxce AneKceee Ko3JIo3oI nocBaeTca 0NTEN page Acknowledgments j Summary ii List of Abbreviations I Principles of Comparison i 1. The reasons for comparison i 2. The type of archives ("chancellery" and "economic" archives) 3 3. The types of the texts 6 4. The arrangement of the texts (colophons and headings) 9 5. The dating systems 6. The "emergency situation" 16 Note5 18 II Lists of Personnel 24 1. Women with children 24 2. Lists of men (classification) 3. Lists of men (discussion) 59 a. Records of work-teams 59 b. Quotas of conscripts 84 o. Personnel of the "households" 89 4. Conclusions 92 Notes 94 III Cultic Personnel (ration lists) 107 Notes 122 IV Assignment of Manpower 124. l.An&)7 124 2. An 1281 128 3. Tn 316 132 4.. Conclusions 137 Notes 139 V Agricultural Manpower (land-surveys) 141 Notes 162 page VI DA-MO and IX)-E-R0 (wnclusions) 167 1. cia-mo 167 2. do-e-io 173 3. Conclusions 181 No tes 187 Indices 193 1. Lexical index 194 2. Index of texts 202 Appendix 210 1. Texts 211 2. Plates 226 -I - Acknowledgments I thank all my teachers in London and Jerusalem . Particularly, I am grateful to Dadid Ashen to whom I owe the very idea to initiate this research, to Amlie Kuhrt and James T. -

Cv Palaimathomascola20199

01_26_2019 Palaima p. 1 Thomas G. PALAIMA red indicates activities & publications 09012018 – 10282019 green 09012016 – 08312018 Robert M. Armstrong Centennial Professor of Classics BIRTH: October 6, 1951 Cleveland, Ohio Director, Program in Aegean Scripts and Prehistory TEL: (512) 471-8837 or 471-5742 CLASSICS E-MAIL: [email protected] University of Texas at Austin FAX: 512 471-4111 WEB: https://sites.utexas.edu/scripts/ 2210 Speedway C3400 profile: http://www.utexas.edu/cola/depts/classics/faculty/palaimat Austin, TX 78712-1738 war and violence Dylanology: https://sites.utexas.edu/tpalaima/ Education/Degrees: University of Uppsala, Ph.D. honoris causa 1994 University of Wisconsin, Ph.D. (Classics) 1980 American School of Classical Studies at Athens, 1976-77, 1979-80 ASCSA Excavation at Ancient Corinth April-July 1977 Boston College, B.A. (Mathematics and Classics) 1973 Goethe Institute, W. Germany 1973 POSITIONS: Raymond F. Dickson Centennial Professor of Classics, UT Austin, 1991-2011 Robert M. Armstrong Centennial Professor of Classics, UT Austin, 2011- Director PASP 1986- Chair, Dept. of Classics, UT Austin, 1994-1998 2017-2018 Cooperating Faculty Center for Middle Eastern Studies Thomas Jefferson Center for the Study of Core Texts and Ideas Center for European Studies Fulbright Professorship, Universidad Autonoma de Barcelona, February-June 2007 Visiting Professor, University of Uppsala April-May 1992, May 1998 visitor 1994, 1999, 2004 Fulbright Gastprofessor, Institut für alte Geschichte, University of Salzburg 1992-93 -

GENDER and CRISIS in GREECE Author(S)

Th e ‘Aft erlife’ of Cheap Labour: Bangalore Garment Female Employment & FEDI Dynamics of Inequality Research Network Workers from Factories to the Informal Economy FEDI Female Employment & Dynamics of Inequality Research Network GENDER AND CRISIS IN GREECE Author(s): Antigone Lyberaki and Platon Tinios Country Briefing Paper No: 06.17.9 1 GENDER AND CRISIS IN GREECE Antigone Lyberaki and Platon Tinios Prepared for the Project Dynamics of Gender Inequality in the Middle East, North Africa and South Asia (ESRC Global Challenges Research Fund) London Conference, 9-10 June 2017 Background: As in other southern European economies, women’s employment rates in Greece started from a very low point but did a lot of catching up until the of the financial crisis after 2008. Indeed, there has been explicit and vocal policy activism since the end of the dictatorship in the mid-1970s to redress some of the most salient aspects of gender discrimination in the legal framework and gender gaps in economic outcomes, with a focus on employment. It is useful to situate the gender trends in the context of three distinct periods. In the first phase, from WW2 to 1980, Greece was a more-or-less successful developing economy, trying to qualify for what was then the European Community. This was the time of the explicit “male-breadwinner model”. Very few women were in employment – just three out of ten – and of those who were working, one out of three had the status of “unpaid family member”. The context was one of fast growth, a large primary sector, big and closely knit families, urbanization and fluid borders between the family firm/farm and the family. -

This Pdf of Your Paper in Aegean Scripts, Proceedings of the 14Th International Colloquium on Mycenaean Studies Belongs to the P

This pdf of your paper in Aegean Scripts, Proceedings of the 14th International Colloquium on Mycenaean Studies belongs to the publisher Istituto di Studi sul Mediterraneo Antico (Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche) and it is its copyright. As author you are licensed to make up to 50 offprints from it, but beyond that you may not make it available on the Internet until two years from publication (December 2017). I CNR ISTITUTO DI STUDI SUL MEDITERRANEO ANTICO II INCUNABULA GRAECA VOL. CV, 1 DIRETTORI MARCO BETTELLI · MAURIZIO DEL FREO COMITATO SCIENTIFICO AEGEAN SCRIPTS JOHN BENNET (Sheffield) · ELISABETTA BORGNA (Udine) Proceedings of the 14th International Colloquium on Mycenaean Studies ANDREA CARDARELLI (Roma) · ANNA LUCIA D’AGATA (Roma) Copenhagen, 2-5 September 2015 PIA DE FIDIO (Napoli) · JAN DRIESSEN (Louvain-la-Neuve) BIRGITTA EDER (Wien) · ARTEMIS KARNAVA (Berlin) Volume I JOHN T. KILLEN (Cambridge) · JOSEPH MARAN (Heidelberg) PIETRO MILITELLO (Catania) · MASSIMO PERNA (Napoli) FRANÇOISE ROUGEMONT (Paris) · JEREMY B. RUTTER (Dartmouth) GERT JAN VAN WIJNGAARDEN (Amsterdam) · CARLOS VARIAS GARCÍA (Barcelona) JÖRG WEILHARTNER (Salzburg) · JULIEN ZURBACH (Paris) PUBBLICAZIONI DELL'ISTITUTO DI STUDI SUL MEDITERRANEO ANTICO DEL CONSIGLIO NAZIONALE DELLE RICERCHE DIRETTORE DELL'ISTITUTO: ALESSANDRO NASO III INCUNABULA GRAECA VOL. CV, 1 DIRETTORI MARCO BETTELLI · MAURIZIO DEL FREO COMITATO SCIENTIFICO AEGEAN SCRIPTS JOHN BENNET (Sheffield) · ELISABETTA BORGNA (Udine) Proceedings of the 14th International Colloquium on Mycenaean Studies ANDREA CARDARELLI (Roma) · ANNA LUCIA D’AGATA (Roma) Copenhagen, 2-5 September 2015 PIA DE FIDIO (Napoli) · JAN DRIESSEN (Louvain-la-Neuve) BIRGITTA EDER (Wien) · ARTEMIS KARNAVA (Berlin) Volume I JOHN T. KILLEN (Cambridge) · JOSEPH MARAN (Heidelberg) PIETRO MILITELLO (Catania) · MASSIMO PERNA (Napoli) FRANÇOISE ROUGEMONT (Paris) · JEREMY B. -

Mast@CHS – Fall Seminar 2020 (Friday, November 6): Summaries of Presentations and Discussion

Classical Inquiries About Us Bibliographies The CI Poetry Project MASt@CHS – Fall Seminar 2020 (Friday, November 6): Summaries of Presentations and Discussion Rachele Pierini DECEMBER 23, 2020 | Guest Post $ # ! & ﹽ 2020.12.23. | By Rachele Pierini and Tom Palaima YOU MAY ALSO LIKE §0.1. Rachele Pierini opened the November session of MASt@CHS, which was the sixth Welcome! in the series and marked one year of MASt seminars—you can read here further details NEWS 9 FEBRUARY 2015 about the MASt project. Pierini also introduced the presenters for this meeting: Anne Chapin, who joined the team for the first time, and the regular members Vassilis Petrakis God-Hero Antagonism in the and Tom Palaima. Finally, Pierini welcomed the rest of the participants: Gregory Nagy, Hippolytus of Euripides Roger Woodard, Leonard Muellner, Hedvig Landenius Enegren, and Georgia Flouda. BY GREGORY NAGY H24H 14 FEBRUARY 2015 §0.2. Anne Chapin delivered a presentation about the visual impact of textile patterns in The Barley Cakes of Sosipolis and Aegean Bronze Age painting, focusing on the exploitation of artistic elements and design Eileithuia principles by Aegean artists. Vassilis Petrakis presented some implications that the study BY GREGORY NAGY H24H of stirrup jars and their trade provides for the reconstruction of Mycenaean societies, both 20 FEBRUARY 2015 in mainland Greece and Crete. Finally, Tom Palaima prepared the ground for the opening discussion of the next MASt session, presenting the controversial figure of the *a-mo-te-u on Pylos tablets through his appearance on PY Ta 711. In the next meeting, Palaima will lead us in a survey of Greek literary and linguistic material to reconstruct the functions and prerogatives of this Mycenaean ofcial. -

Monday 16 June 2014 – Afternoon

F Monday 16 June 2014 – Afternoon GCSE CLASSICAL CIVILISATION A353/01 Community Life in the Classical World (Foundation Tier) *1238732213* Candidates answer on the Question Paper. OCR supplied materials: Duration: 1 hour None Other materials required: None *A35301* INSTRUCTIONS TO CANDIDATES • Write your name, centre number and candidate number in the boxes above. Please write clearly and in capital letters. • Use black ink. HB pencil may be used for graphs and diagrams only. • There are two options in this paper: Option 1: Sparta, with questions starting on page 2. Option 2: Pompeii, with questions starting on page 16. • Answer questions from either Option 1 or Option 2. • Answer all questions from Section A and two questions from Section B of the option that you have studied. • Read each question carefully. Make sure you know what you have to do before starting your answer. • Write your answer to each question in the space provided. If additional space is required, you should use the lined pages at the end of this booklet. The question number(s) must be clearly shown. • Do not write in the bar codes. INFORMATION FOR CANDIDATES • The number of marks is given in brackets [ ] at the end of each question or part question. • The total number of marks for this paper is 60. • This document consists of 32 pages. Any blank pages are indicated. © OCR 2014 [A/501/5549] OCR is an exempt Charity DC (DTC 00708 10/12) 71715/3 Turn over 2 Option 1: Sparta Answer all of Section A and two questions from Section B.