The Effects of Mythos' on Plato's Educational Approach

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ancient Sparta Was a Warrior Society in Ancient Greece That Reached

Ancient Sparta was a warrior society in ancient Greece that reached the height of its power after defeating rival city-state Athens in the Peloponnesian War (431-404 B.C.). Spartan culture was centered on loyalty to the state and military service. At age 7, Spartan boys entered a rigorous state-sponsored education, military training and socialization program. Known as the Agoge, the system emphasized duty, discipline and endurance. Although Spartan women were not active in the military, they were educated and enjoyed more status and freedom than other Greek women. Because Spartan men were professional soldiers, all manual labor was done by a slave class, the Helots. Despite their military prowess, the Spartans’ dominance was short-lived: In 371 B.C., they were defeated by Thebes at the Battle of Leuctra, and their empire went into a long period of decline. SPARTAN SOCIETY Sparta was an ancient Greek city-state located primarily in the present-day region of southern Greece called Laconia. The population of Sparta consisted of three main groups: the Spartans who were full citizens; the Helots, or serfs/slaves; and the Perioeci, who were neither slaves nor citizens. The Perioeci, whose name means “dwellers-around,” worked as craftsmen and traders, and built weapons for the Spartans. 3 Layers of ‘Social Stratification’ ← Top Tier: Spartan Male Warriors and Spartan Women ← Middle Tier: Non Warriors, not full citizens, considered to be outside of true Spartan society. These were artisans and merchants who made weapons and did business with the Spartans. (Perioeci) ← Helots or slaves. These were people who were conquered by the Spartans. -

Continuity in Color: the Persistence of Symbolic Meaning in Myths, Tales, and Tropes

Georgia Southern University Digital Commons@Georgia Southern University Honors Program Theses 2016 Continuity in Color: The eP rsistence of Symbolic Meaning in Myths, Tales, and Tropes McKinley May Georgia Southern University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/honors-theses Part of the Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons Recommended Citation May, McKinley, "Continuity in Color: The eP rsistence of Symbolic Meaning in Myths, Tales, and Tropes" (2016). University Honors Program Theses. 170. https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/honors-theses/170 This thesis (open access) is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. It has been accepted for inclusion in University Honors Program Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Continuity in Color: The Persistence of Symbolic Meaning in Myths, Tales, and Tropes An Honors Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Honors in the Department of Literature and Philosophy. By McKinley May Under the mentorship of Joe Pellegrino ABSTRACT This paper examines the symbolism of the colors black, white, and red from ancient times to modern. It explores ancient myths, the Grimm canon of fairy tales, and modern film and television tropes in order to establish the continuity of certain symbolisms through time. In regards to the fairy tales, the examination focuses solely on the lesser-known stories, due to the large amounts of scholarship surrounding the “popular” tales. The continuity of interpretation of these three major colors (black, white, and red) establishes the link between the past and the present and demonstrates the influence of older myths and beliefs on modern understandings of the colors. -

Phd Thesis Chapter 1

The Regulation of Stress-Induced Proanthocyanidin Metabolism in Poplar by Robin D. Mellway B. Sc., University of Victoria, 2003 A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in the Department of Biology Robin D. Mellway, 2009 University of Victoria All rights reserved. This thesis may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without the permission of the author. Library and Archives Bibliothèque et Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de l’édition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-66841-2 Our file Notre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-66841-2 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non- L’auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant à la Bibliothèque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par télécommunication ou par l’Internet, prêter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des thèses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, à des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non- support microforme, papier, électronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L’auteur conserve la propriété du droit d’auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protège cette thèse. Ni thesis. -

Dictynna, 16 | 2019 the Shade of Orpheus : Ambiguity and the Poetics of Vmbra in Metamorphoses 10 2

Dictynna Revue de poétique latine 16 | 2019 Varia The Shade of Orpheus : Ambiguity and the Poetics of Vmbra in Metamorphoses 10 Celia Campbell Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/dictynna/1814 DOI: 10.4000/dictynna.1814 ISSN: 1765-3142 Electronic reference Celia Campbell, « The Shade of Orpheus : Ambiguity and the Poetics of Vmbra in Metamorphoses 10 », Dictynna [Online], 16 | 2019, Online since 19 December 2019, connection on 11 September 2020. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/dictynna/1814 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/dictynna.1814 This text was automatically generated on 11 September 2020. Les contenus des la revue Dictynna sont mis à disposition selon les termes de la Licence Creative Commons Attribution - Pas d'Utilisation Commerciale - Pas de Modification 4.0 International. The Shade of Orpheus : Ambiguity and the Poetics of Vmbra in Metamorphoses 10 1 The Shade of Orpheus : Ambiguity and the Poetics of Vmbra in Metamorphoses 10 Celia Campbell 1 In Book 10, the narrative reins of Ovid’s Metamorphoses are ceded to the constructed whims of a notable internal poet-singer : the mythical bard Orpheus. In this way, Orpheus follows in the footsteps of his mother, the Muse Calliope, who is granted a large portion of narrative space within Book 5, similarly occupying a pentadic structural point within the epic. These acts of internal narration are, however, not just linked structurally, nor by the loosely imposed idea of a continuity established through generational descent, but are affiliated through the circumstance of their staging. The communication of Calliope’s narrative is predicated on a poetic covenant familiarised by the pastoral tradition : the Muse asks her audience, the goddess Minerva, if she has sufficient leisure (otia, Met. -

Robert Graves the White Goddess

ROBERT GRAVES THE WHITE GODDESS IN DEDICATION All saints revile her, and all sober men Ruled by the God Apollo's golden mean— In scorn of which I sailed to find her In distant regions likeliest to hold her Whom I desired above all things to know, Sister of the mirage and echo. It was a virtue not to stay, To go my headstrong and heroic way Seeking her out at the volcano's head, Among pack ice, or where the track had faded Beyond the cavern of the seven sleepers: Whose broad high brow was white as any leper's, Whose eyes were blue, with rowan-berry lips, With hair curled honey-coloured to white hips. Green sap of Spring in the young wood a-stir Will celebrate the Mountain Mother, And every song-bird shout awhile for her; But I am gifted, even in November Rawest of seasons, with so huge a sense Of her nakedly worn magnificence I forget cruelty and past betrayal, Careless of where the next bright bolt may fall. FOREWORD am grateful to Philip and Sally Graves, Christopher Hawkes, John Knittel, Valentin Iremonger, Max Mallowan, E. M. Parr, Joshua IPodro, Lynette Roberts, Martin Seymour-Smith, John Heath-Stubbs and numerous correspondents, who have supplied me with source- material for this book: and to Kenneth Gay who has helped me to arrange it. Yet since the first edition appeared in 1946, no expert in ancient Irish or Welsh has offered me the least help in refining my argument, or pointed out any of the errors which are bound to have crept into the text, or even acknowledged my letters. -

Not All Were Created Equal

Portland State University PDXScholar Young Historians Conference 2010-2011 Past Young Historians Conference Winners May 1st, 9:00 AM - 10:00 AM Not All Were Created Equal Sarah Cox Clackamas High School Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/younghistorians Part of the Ancient History, Greek and Roman through Late Antiquity Commons, History of Gender Commons, and the Women's History Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Cox, Sarah, "Not All Were Created Equal" (2011). Young Historians Conference. 3. https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/younghistorians/2010-2011/oralpres/3 This Event is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Young Historians Conference by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. Cox 1 Sarah Cox LPB Western Civilization: Fall Paper 9 December 2010 Not All Were Created Equal “The man’s role requires him to be outside – men who stay at home during the day are considered womanish – the woman’s requires her to work at home” (McAuslan 137). In the time-period between 700 and 300 BCE, this was often true for the women of the world, but there was one major exception: Spartan women. In most other parts of ancient Greece, women were expected to be seen and not heard. Spartan women, however, were allowed much more freedom than their contemporaries. They were allowed to own property, could live independently, and were not forced into marriage and motherhood at a young age. -

A Brief History of Classical Education

A Brief History of Classical Lesson 4: The History of Ancient Education Education Dr. Matthew Post Outline: Ancient Education and Its Questions Ancient Education is all about character formation. The question is “What sort of character?” What are the morals towards which to form students? Scholé presents another issue. Ancients had less time to devote to proper scholé. The presence of corporeal punishment was questioned by many because it seemed to treat students as slaves (coercing them to do their work through physical pain). The “intellectual life” caused controversy because it often raised questions that unsettled the normal order. (i.e. Cicero held that the ideas of the Stoics made people complacent in the face of evil and some held that Plato’s ideas inspired people to go and assassinate the ruler of their town) Roman Education Three outcomes: Philosopher, Statesman, and Soldier Discussion of Liberal Arts originates in Rome especially with Cicero (without formalization of Medieval period) Education connected to the idea of pietas (from which we get the English words “piety” and “pity”). Pietas does not mean “piety,” it means “loyalty.” o Pietas is loyalty to one’s family, people, city, and the gods. Loyalty to the gods is what the English notion of piety refers to, but pietas encompasses more. Traditional Roman education is dictated by the paterfamilias (the head of the family – a father with power over all and everything in the family). “Aeneas & Anchises” by Pierre Lepautre (a famous show of pietas) o The paterfamilias often educated the children himself. (Famously Cato the Elder educated his children.) Education in the Roman family was for both men and women though they were educated differently. -

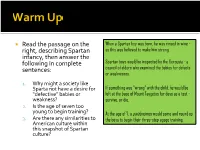

Ancient Sparta Ancient Athens

Read the passage on the When a Spartan boy was born, he was rinsed in wine - right, describing Spartan as this was believed to make him strong. infancy, then answer the following in complete Spartan boys would be inspected by the Gerousia - a sentences: council of elders who examined the babies for defects or weaknesses. 1. Why might a society like Sparta not have a desire for If something was “wrong” with the child, he would be “defective” babies or left at the base of Mount Taygetus for days as a test - weakness? survive, or die. 2. Is the age of seven too young to begin training? At the age of 7, a paidonómos would come and round up 3. Are there any similarities to the boys to begin their three-step agoge training. American culture within this snapshot of Spartan culture? Title: Comparative Study; Eastern Bloc and Worldly Civilizations Date: Know: I will be able to identify, describe, and analyze the similarities and differences of political involvement in livelihood across millennia. Relevance: Today we are learning about this because it is imperative to build knowledge in a pragmatic way – understanding that the real world and real life are connected to history is very important. Coming to this understanding is powerful! Do: I will write and discuss comparative issues between Ancient Greek city-states Do: I will write and discuss comparative issues between Medieval nations Do: I will write and discuss comparative issues between modern countries Write down the Essential Question: EQ: which child-rearing system had the greatest impact on population regulation? Warm Up Cornell Notes . -

VALOUR, DUTY, SACRIFICE: SPARTA ‘In Sparta Are to Be Found Those Who Are Most Enslaved and Those Who Are the Most Free.’

CHAPTER 2 VALOUR, DUTY, SACRIFICE: SPARTA ‘In Sparta are to be found those who are most enslaved and those who are the most free.’ CRITIAS OF ATHENS sample pages Spartan infantry in a formation called a phalanx. 38 39 CHAPTER 2 VALOUR, DUTY, SACRIFICE: SPARTA KEY POINTS KEY CONCEPTS OVERVIEW • At the end of the Dark Age, the Spartan polis emerged DEMOCRACY OLIGARCHY TYRANNY MONARCHY from the union of a few small villages in the Eurotas valley. Power vested in the hands Power vested in the hands A system under the control A system under the control • Owing to a shortage of land for its citizens, Sparta waged of all citizens of the polis of a few individuals of a non-hereditary ruler of a king war on its neighbour Messenia to expand its territory. unrestricted by any laws • The suppression of the Messenians led to a volatile slave or constitution population that threatened Sparta’s way of life, making the DEFINITION need for reform urgent. KEY EVENTS • A new constitution was put in place to ensure Sparta could protect itself from this new threat, as well as from tyranny. Citizens of the polis all A small, powerful and One individual exercises Hereditary rule passing 800 BCE • Sweeping reforms were made that transformed Sparta share equal rights in the wealthy aristocratic class complete authority over from father to son political sphere all aspects of everyday life Sparta emerges from the into a powerful military state that soon came to dominate Most citizens barred from Family dynasties claim without constraint Greek Dark Age the Peloponnese. -

ATLAS of CLASSICAL HISTORY

ATLAS of CLASSICAL HISTORY EDITED BY RICHARD J.A.TALBERT London and New York First published 1985 by Croom Helm Ltd Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2003. © 1985 Richard J.A.Talbert and contributors All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Atlas of classical history. 1. History, Ancient—Maps I. Talbert, Richard J.A. 911.3 G3201.S2 ISBN 0-203-40535-8 Master e-book ISBN ISBN 0-203-71359-1 (Adobe eReader Format) ISBN 0-415-03463-9 (pbk) Library of Congress Cataloguing in Publication Data Also available CONTENTS Preface v Northern Greece, Macedonia and Thrace 32 Contributors vi The Eastern Aegean and the Asia Minor Equivalent Measurements vi Hinterland 33 Attica 34–5, 181 Maps: map and text page reference placed first, Classical Athens 35–6, 181 further reading reference second Roman Athens 35–6, 181 Halicarnassus 36, 181 The Mediterranean World: Physical 1 Miletus 37, 181 The Aegean in the Bronze Age 2–5, 179 Priene 37, 181 Troy 3, 179 Greek Sicily 38–9, 181 Knossos 3, 179 Syracuse 39, 181 Minoan Crete 4–5, 179 Akragas 40, 181 Mycenae 5, 179 Cyrene 40, 182 Mycenaean Greece 4–6, 179 Olympia 41, 182 Mainland Greece in the Homeric Poems 7–8, Greek Dialects c. -

Divine Riddles: a Sourcebook for Greek and Roman Mythology March, 2014

Divine Riddles: A Sourcebook for Greek and Roman Mythology March, 2014 E. Edward Garvin, Editor What follows is a collection of excerpts from Greek literary sources in translation. The intent is to give students an overview of Greek mythology as expressed by the Greeks themselves. But any such collection is inherently flawed: the process of selection and abridgement produces a falsehood because both the narrative and meta-narrative are destroyed when the continuity of the composition is interrupted. Nevertheless, this seems the most expedient way to expose students to a wide range of primary source information. I have tried to keep my voice out of it as much as possible and will intervene as editor (in this Times New Roman font) only to give background or exegesis to the text. All of the texts in Goudy Old Style are excerpts from Greek or Latin texts (primary sources) that have been translated into English. Ancient Texts In the field of Classics, we refer to texts by Author, name of the book, book number, chapter number and line number.1 Every text, regardless of language, uses the same numbering system. Homer’s Iliad, for example, is divided into 24 books and the lines in each book are numbered. Hesiod’s Theogony is much shorter so no book divisions are necessary but the lines are numbered. Below is an example from Homer’s Iliad, Book One, showing the English translation on the left and the Greek original on the right. When citing this text we might say that Achilles is first mentioned by Homer in Iliad 1.7 (i.7 is also acceptable). -

Monday 16 June 2014 – Afternoon

F Monday 16 June 2014 – Afternoon GCSE CLASSICAL CIVILISATION A353/01 Community Life in the Classical World (Foundation Tier) *1238732213* Candidates answer on the Question Paper. OCR supplied materials: Duration: 1 hour None Other materials required: None *A35301* INSTRUCTIONS TO CANDIDATES • Write your name, centre number and candidate number in the boxes above. Please write clearly and in capital letters. • Use black ink. HB pencil may be used for graphs and diagrams only. • There are two options in this paper: Option 1: Sparta, with questions starting on page 2. Option 2: Pompeii, with questions starting on page 16. • Answer questions from either Option 1 or Option 2. • Answer all questions from Section A and two questions from Section B of the option that you have studied. • Read each question carefully. Make sure you know what you have to do before starting your answer. • Write your answer to each question in the space provided. If additional space is required, you should use the lined pages at the end of this booklet. The question number(s) must be clearly shown. • Do not write in the bar codes. INFORMATION FOR CANDIDATES • The number of marks is given in brackets [ ] at the end of each question or part question. • The total number of marks for this paper is 60. • This document consists of 32 pages. Any blank pages are indicated. © OCR 2014 [A/501/5549] OCR is an exempt Charity DC (DTC 00708 10/12) 71715/3 Turn over 2 Option 1: Sparta Answer all of Section A and two questions from Section B.