Hume-Arg Philosophers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Philosophisches Seminar Kommentiertes

Philosophisches Seminar Kommentiertes Vorlesungsverzeichnis Sommersemester 2013 Stand: 05.03.2013 Inhalt: Übersicht 6 Vorlesungen 6, 17 Hauptseminare 7, 22 Propädeutikum 6, 21 Proseminare 10, 36 Hauptseminare 7, 47 Kolloquien 14, 49 Fachdidaktik 14, 50 Ethisch-Philosophisches Grundlagenstudium – EPG 15, 51 Kommentare 17 Hinweise und Abkürzungen 5 Dozenten: Aleksan, Gilbert EPG I: Einführung in die antike Ethik 51 Aleksan, Gilbert EPG I: Kant, Kritik der praktischen Vernunft 52 Álvarez-Vázquez, Javier PS: Historisch-genetische Theorie der Kognition 36 Arnold, Florian EPG I: Fichtes Bestimmungen des Gelehrten 52 Arnold, Thomas PS: Edmund Husserl, Phänomenologische Psychologie 36 Corall, Niklas EPG I: Moralkritik von der Antike bis zur Neuzeit 53 Cürsgen, Dirk V: Kants praktische Philosophie 17 Dangel, Tobias HS: Phänomenologie des Geistes II 22 Dangel, Tobias PS: Platon, Sophistes 37 Diehl, Ulrich PS: Kants Konzeption der Würde. Interpretation und Dis- kussion 37 Dierig, Simon PS: Einführung in Descartes’ Philosophie 39 Dilcher, Roman EPG I: Platon, Gorgias 54 Dilcher, Roman PS: Aristoteles, Nikomachische Ethik 39 Enßlen, Michael EPG II: Das deutsche Atombombenprojekt 59 Flickinger, Brigitte EPG I: Soziale Gerechtigkeit – eine künstliche Tugend? 54 Franceschini, Stefano EPG II: Spinozas Reflexion über den Mensch 59 Freitag, Wolfgang HS: Grundlegende Texte zur philosophischen Semantik 40 Freitag, Wolfgang Kolloquium 49 Freitag, Wolfgang PS: Einführung in die (analytische) Philosophie der Zeit 22 Freitag, Wolfgang V: Sprachliche Bedeutung: -

Locke, God, and Materialism (Preprint)

Locke, God, and Materialism Stewart Duncan Forthcoming in Oxford Studies in Early Modern Philosophy 1. INTRODUCTION Early modern philosophers discussed several versions of materialism. One distinction among them is that of scope. Should one be a materialist about animal minds, human minds, the whole of nature, or God? Hobbes eventually said ‘yes’ to all four questions, and Spinoza seemed to several of his readers to have done the same. Locke, however, gave different answers to the different questions. Though there is some debate about these matters, it appears that he thought materialism about God was mistaken, was agnostic about whether human minds were material, and was inclined to think that animal minds were material.1 In giving those answers, Locke famously suggested the possibility that God might have ‘superadded’ thought to the matter of our bodies, giving us the power of thought without immaterial thinking minds. He thus opened up the possibility of materialism about human minds, without adopting the sort of general materialist metaphysics that Hobbes, for example, had proposed. This paper investigates Locke’s views about materialism, by looking at the discussion in Essay IV.x. There Locke—after giving a cosmological argument for the existence of God— argues that God could not be material, and that matter alone could never produce thought.2 In 1 On Locke on animals’ minds, see Lisa Downing, ‘Locke’s Choice Between Materialism and Dualism’ [‘Locke’s Choice’], in Paul Lodge and Tom Stoneham (ed.), Locke and Leibniz on Substance (New York: Routledge, 2015), 128-45; Nicholas Jolley, Locke’s Touchy Subjects (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015), 33-49; and Kathleen Squadrito, ‘Thoughtful Brutes: The Ascription of Mental Predicates to Animals in Locke’s Essay’, Diálogos 58 (1991), 63-73. -

Conflicts Between Science and Religion: Epistemology to the Rescue

Conflicts Between Science and Religion: Epistemology to the Rescue Moorad Alexanian Department of Physics and Physical Oceanography University of North Carolina Wilmington Wilmington, NC 28403-5606 (Dated: April 23, 2021) Both Albert Einstein and Erwin Schr¨odinger have defined what science is. Einstein includes not only physics, but also all natural sciences dealing with both organic and inorganic processes in his definition of science. According to Schr¨odinger, the present scientific worldview is based on the two basic attitudes of comprehensibility and objectivation. On the other hand, the notion of religion is quite equivocal and unless clearly defined will easily lead to all sorts of misunderstandings. Does science, as defined, encompass the whole of reality? More importantly, what is the whole of reality and how do we obtain data for it? The Christian worldview considers a human as body, mind, and spirit (soul), which is consistent with Cartesian ontology of only three elements: matter, mind, and God. Therefore, is it possible to give a precise definition of science showing that the conflicts are actually apparent and not real? I. INTRODUCTION In 1950, Albert Einstein gave a remarkable lecture to the International Congress of Surgeons in Cleveland, Ohio. Einstein argued that the 19th-century physicists’ simplistic view of Nature gave biologists the confidence to treat life as a purely physical phenomenon. This mechanistic picture of Nature was based on the casual laws of Newtonian mechanics and the Faraday-Maxwell theory of electromagnetism. These causal laws proved to be wanting, especially in atomistic phenomena, which brought about the advent of quantum mechanics in the 20th-century. -

Conciencia Y Paralelismo En Spinoza

Discusión Conciencia y paralelismo en Spinoza Luis Ángel García Muñoz Departamento de Filosofía Universidad Autónoma de Aguascalientes [email protected] En su obra más representativa, la Ethica ordine geometrico demostrata (específi camente en su segunda parte), Spinoza sugiere que todo individuo, sea humano, animal o un objeto extenso cualquiera, está animado en cierto grado (E IIP13s). Y por si fuera poco, que los indi- viduos inferiores como animales u objetos extensos tienen mente. Este asunto, potencialmente agresivo para el sentido común, es tratado por Edwin Curley, quien trata de ofrecer una distinción entre los hombres y los demás individuos con la fi nalidad de expli- car el sistema de Spinoza sin caer en sugerencias tan problemáticas. Esta distinción se encuentra en su libro Spinoza’s Metaphysics: An Essay in Interpretation publicado en 1969, en el que defi ende que, en Spinoza, todos los individuos que están en Dios tienen mente. Pero los hombres se distinguen de los demás individuos (rocas, animales, etc.) porque sólo los primeros, además de tener mente, tienen conciencia. Lo que caracteriza a la conciencia en Spinoza, se- gún Curley, es la posesión de ideas de ideas o bien de proposiciones de proposiciones.1 Así, aunque todos los individuos, en Spinoza tengan mente, los hombres se distinguen de los demás individuos porque sólo ellos poseen ideas de ideas o proposiciones de proposiciones. 1 Esta caracterización de la conciencia es adoptada por Curley al haber reinterpretado la teoría de las ideas en Spinoza y al haber encontrado en ellas ‘un elemento de afi rmación’ que permite equipararlas con las proposiciones. -

Quantum Computing: Progress and Prospects (2018)

THE NATIONAL ACADEMIES PRESS This PDF is available at http://nap.edu/25196 SHARE Quantum Computing: Progress and Prospects (2018) DETAILS 202 pages | 6 x 9 | PAPERBACK ISBN 978-0-309-47969-1 | DOI 10.17226/25196 CONTRIBUTORS GET THIS BOOK Emily Grumbling and Mark Horowitz, Editors; Committee on Technical Assessment of the Feasibility and Implications of Quantum Computing; Computer Science and Telecommunications Board; Intelligence Community Studies Board; Division on FIND RELATED TITLES Engineering and Physical Sciences; National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine SUGGESTED CITATION National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine 2018. Quantum Computing: Progress and Prospects. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/25196. Visit the National Academies Press at NAP.edu and login or register to get: – Access to free PDF downloads of thousands of scientific reports – 10% off the price of print titles – Email or social media notifications of new titles related to your interests – Special offers and discounts Distribution, posting, or copying of this PDF is strictly prohibited without written permission of the National Academies Press. (Request Permission) Unless otherwise indicated, all materials in this PDF are copyrighted by the National Academy of Sciences. Copyright © National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved. Quantum Computing: Progress and Prospects PREPUBLICATION COPY – SUBJECT TO FURTHER EDITORIAL CORRECTION Quantum Computing: Progress and Prospects Emily Grumbling and Mark Horowitz, Editors Committee on Technical Assessment of the Feasibility and Implications of Quantum Computing Computer Science and Telecommunications Board Intelligence Community Studies Board Division on Engineering and Physical Sciences A Consensus Study Report of PREPUBLICATION COPY – SUBJECT TO FURTHER EDITORIAL CORRECTION Copyright National Academy of Sciences. -

Consciousness, Ideas of Ideas and Animation in Spinoza's Ethics

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Groningen University of Groningen Consciousness, ideas of ideas and animation in Spinoza’s Ethics Marrama, Oberto Published in: British Journal for the History of Philosophy DOI: 10.1080/09608788.2017.1322038 IMPORTANT NOTE: You are advised to consult the publisher's version (publisher's PDF) if you wish to cite from it. Please check the document version below. Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Publication date: 2017 Link to publication in University of Groningen/UMCG research database Citation for published version (APA): Marrama, O. (2017). Consciousness, ideas of ideas and animation in Spinoza’s Ethics. British Journal for the History of Philosophy, 25(3), 506-525. https://doi.org/10.1080/09608788.2017.1322038 Copyright Other than for strictly personal use, it is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Take-down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Downloaded from the University of Groningen/UMCG research database (Pure): http://www.rug.nl/research/portal. For technical reasons the number of authors shown on this cover page is limited to 10 maximum. Download date: 12-11-2019 British Journal for the History of Philosophy ISSN: 0960-8788 (Print) 1469-3526 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rbjh20 Consciousness, ideas of ideas and animation in Spinoza’s Ethics Oberto Marrama To cite this article: Oberto Marrama (2017) Consciousness, ideas of ideas and animation in Spinoza’s Ethics, British Journal for the History of Philosophy, 25:3, 506-525, DOI: 10.1080/09608788.2017.1322038 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09608788.2017.1322038 © 2017 The Author(s). -

Curriculum Vitae

October 2016 Matthew F. Stuart Curriculum Vitae Department of Philosophy 8400 College Station Bowdoin College Brunswick, Maine 04011 Education: Cornell University, Ph.D. in Philosophy, 1994. Cornell University, M.A. in Philosophy, 1991. University of Vermont, B.A. in Philosophy, 1988. Area of Specialization: Early Modern Philosophy Areas of Competence: Metaphysics, Epistemology, Ethics Teaching Positions: 2012- present Professor, Bowdoin College 1999 - 2012 Associate Professor, Bowdoin College 1994 - 1999 Assistant Professor, Bowdoin College 1993 Instructor, Bowdoin College Publications: BOOKS A Companion to Locke (Editor). Oxford: Wily-Blackwell Publishing Co., 2016. Locke’s Metaphysics. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 2013. Reviewed by Benjamin Hill in Notre Dame Philosophical Reviews (2014); Victor Nuovo in Locke Studies 14 (2014), 263-271; Michael Jacovides in Philosophical Review 124 (2015), 153-155; G. A. J. Rogers in British Journal for the History of Philosophy 23 (2015), 199-202. ARTICLES AND CHAPTERS “Locke’s Succeeding Ideas,” Oxford Studies in Early Modern Philosophy VIII, D. Garber and D. Rutherford, eds., forthcoming. ARTICLES AND CHAPTERS (CONT.) “Locke on Attention,” British Journal for the History of Philosophy, special issue: “Mental Powers in Early Modern Philosophy,” forthcoming. “John Locke and the Problem of Consciousness,” in Consciousness and the Great Philosophers, S. Leach and J. Tartaglia, eds., London: Routledge, 2017, 73-81. “The Correspondence with Stillingfleet,” in A Companion to Locke, M. Stuart ed., London: Wily-Blackwell Publishing Co., 2016, 354-369. “Revisiting People and Substances,” in The Key Debates of Modern Philosophy, S. Duncan and A. LoLordo, eds., Routledge, 2013, 186-196. “Locke,” in A Companion to the Philosophy of Action, T. O’Connor & C. -

Eugene Marshall

Eugene Marshall Contact Department of Philosophy Office: (781) 283-3476 Information Florida International University Department: (781) 283-2620 DM 347 E-mail: [email protected] Miami, FL 33199 WWW: Website Specialty The History of Modern Philosophy Competences Ancient Philosophy, 19th Century German Philosophy, Metaphysics, Moral Psy- chology, Feminist History of Philosophy Education The University of Wisconsin, Madison, WI USA Ph.D., Department of Philosophy, December 2006 Thesis: Akrasia in Spinoza's Ethics, Adviser: Professor Steven Nadler The University of Missouri{St. Louis St. Louis, MO USA B.A., Departments of Philosophy and Psychology, May 2000. Publications Marshall, Eugene. The Spiritual Automaton: Spinoza's Science of the Mind, Oxford University Press, 2013. Marshall, Eugene. How To Teach Modern Philosophy. Teaching Philosophy, Volume 37, Issue 1, March 2014. Marshall, Eugene. Spinoza on Evil. The History of Evil. Volume III: The History of Evil in the Early Modern Age (1450-1700), Acumen Press, forth- coming. Marshall, Eugene. Man is a God to man: How Human Beings Can be Adequate Causes. Essays on Spinoza's Ethical Theory, Matthew Kisner and Andre Youpa, eds., Oxford University Press, 2014. Marshall, Eugene. Spinoza on the Problem of Akrasia. European Journal of Philosophy. 18(1):p 41-59, 2010. Marshall, Eugene. Adequacy and Innateness in Spinoza. Oxford Studies in Early Modern Philosophy, 4: 51-88, 2008. Marshall, Eugene. Spinoza's Cognitive Affects and their Feel. British Journal for the History of Philosophy 16(1): 1-23, 2008. 1 of 4 Book Reviews Review of Susan James, Spinoza on Philosophy, Religion, and Politics: The Theological-Political Treatise, in Journal of the History of Philosophy, 2013. -

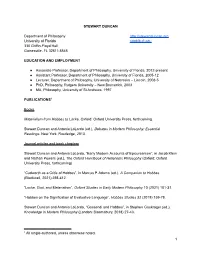

Cv for Stewart Duncan

STEWART DUNCAN Department of Philosophy http://stewartduncan.org University of Florida [email protected] 330 Griffin-Floyd Hall Gainesville, FL 32611-8545 EDUCATION AND EMPLOYMENT ● Associate Professor, Department of Philosophy, University of Florida, 2012-present ● Assistant Professor, Department of Philosophy, University of Florida, 2005-12 ● Lecturer, Department of Philosophy, University of Nebraska – Lincoln, 2003-5 ● PhD, Philosophy, Rutgers University – New Brunswick, 2003 ● MA, Philosophy, University of St Andrews, 1997 PUBLICATIONS1 Books Materialism from Hobbes to Locke. Oxford: Oxford University Press, forthcoming. Stewart Duncan and Antonia LoLordo (ed.), Debates in Modern Philosophy: Essential Readings. New York: Routledge, 2013. Journal articles and book chapters Stewart Duncan and Antonia LoLordo, “Early Modern Accounts of Epicureanism”, in Jacob Klein and Nathan Powers (ed.), The Oxford Handbook of Hellenistic Philosophy (Oxford: Oxford University Press, forthcoming). “Cudworth as a Critic of Hobbes”, in Marcus P. Adams (ed.), A Companion to Hobbes (Blackwell, 2021) 398-412. “Locke, God, and Materialism”, Oxford Studies in Early Modern Philosophy 10 (2021) 101-31. “Hobbes on the Signification of Evaluative Language”, Hobbes Studies 32 (2019) 159-78. Stewart Duncan and Antonia LoLordo, “Gassendi and Hobbes”, in Stephen Gaukroger (ed.), Knowledge in Modern Philosophy (London: Bloomsbury, 2018) 27-43. 1 All single-authored, unless otherwise noted. 1 “Hobbes, Universal Names, and Nominalism”, in Stefano Di Bella and Tad Schmaltz (ed.), The Problem of Universals in Early Modern Philosophy (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017) 41-61. “Toland and Locke in the Leibniz-Burnett Correspondence”, Locke Studies 17 (2017) 117-41. “Hobbes on Language: Propositions, Truth, and Absurdity”, in A.P. Martinich and Kinch Hoekstra (ed.), Oxford Handbook of Hobbes (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016) 57-72. -

Spinoza's Theory of the Human Mind

SPINOZA’S THEORY OF THE HUMAN MIND: CONSCIOUSNESS, MEMORY, AND REASON 1A_BW_Marrama .job © Oberto Marrama, 2019. All rights reserved. ISBN 978-94-034-1568-0 (printed version) ISBN 978-94-034-1569-7 (electronic version) 1B_BW_Marrama .job Spinoza’s Theory of the Human Mind: Consciousness, Memory, and Reason PhD thesis to obtain the degree of PhD at the University of Groningen on the authority of the Rector Magnificus Prof. E. Sterken and in accordance with the decision by the College of Deans; and submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements to obtain the degree of PhD in Philosophy at the Université du Québec à Trois-Rivières. Double PhD degree This thesis will be defended in public on Thursday 16 May 2019 at 11.00 hours by Oberto Marrama born on 27 April 1984 in Arzignano (VI), Italy 2A_BW_Marrama .job Supervisors: Prof. M. Lenz Prof. S. Malinowski-Charles Assessment Committee: Prof. M. Della Rocca Prof. S. James Prof. C. Jaquet Prof. D. H. K. Pätzold 2B_BW_Marrama .job Table of Contents Table of Abbreviations 7 Editorial Note 9 Acknowledgments 11 Introduction 13 Methodological Note 15 Outline of the Chapters 16 Chapter 1: Consciousness, Ideas of Ideas, and Animation in Spinoza’s Ethics 19 1. Introduction 19 2. Two issues concerning Spinoza’s panpsychism 21 3. The current debate 27 4. The terminological gap: conscientia as “consciousness” 31 5. The illusion of free will and the theory of the “ideas of ideas” 35 6. Animation, eternity, and the “third kind of knowledge” 43 7. Two issues concerning Spinoza’s panpsychism solved 54 8. -

Spinoza's Causal Axiom a Defense

Spinoza's Causal Axiom A Defense by Torin Doppelt A thesis submitted to the Department of Philosophy in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Queen's University Kingston, Ontario, Canada September 2010 Copyright c Torin Doppelt, 2010 Library and Archives Bibliothèque et Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de l’édition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-70250-5 Our file Notre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-70250-5 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non- L’auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant à la Bibliothèque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par télécommunication ou par l’Internet, prêter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des thèses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, à des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non- support microforme, papier, électronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L’auteur conserve la propriété du droit d’auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protège cette thèse. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la thèse ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent être imprimés ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. -

Curriculum Vitae

Kurt Smith, Ph.D. CURRICULUM VITAE 218 Bakeless Center for the Humanities Department of Philosophy Bloomsburg University of Pennsylvania Bloomsburg, PA 17815 (570) 389-4331 (Office) [email protected] Degrees Ph.D. in philosophy, 1998, Claremont Graduate University, Claremont, CA M.A. in philosophy, 1993, Claremont Graduate University B.A. in philosophy, 1991, University of California, Irvine, CA Area of Specialization History of Early Modern Philosophy Areas of Competence Philosophy of Mathematics (early modern), Philosophy of Mind (early modern), Ancient Philosophy, Medieval Philosophy, Nineteenth- and Twentieth-Century Analytic Philosophy, Philosophy of Religion, and Philosophy of Social Science Appointments Professor, Bloomsburg University, 2013-present Associate Professor, Bloomsburg University, 2005-2013 Assistant Professor, Bloomsburg University, 1999-2005 Visiting Assistant Professor, Claremont McKenna College, 1998-99 ____________ • Visiting Fellow, Princeton University, Fall 2014 • Visiting Fellow, Princeton University, Spring 2007 Research Books (1) Matter Matters: Metaphysics and Methodology in the Early Modern Period. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010, Paperback 2012. (2) The Descartes Dictionary. London: Bloomsbury Press, 2015. (3) This is Modern Philosophy: An Introduction. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell Publishing, forthcoming 2018. (4) Simply Descartes. New York: Simply Charly Press, forthcoming 2018. Articles and Book Chapters (5) “Meditations by René Descartes” in Arc Digital’s Medium series: The Greatest Works in Philosophy, November 2, 2017 (online). URL = https://arcdigital.media/meditations-by-rene-descartes-5cfee16db7d9 (6) “Descartes on Ideas,” in The Cartesian Mind, Jorge Secada and Cecelia Wee (eds), London: Routledge, forthcoming 2018. (7) “Leibniz on Order, Harmony, and the Notion of Substance: Mathematizing the Sciences of Metaphysics and Physics,” in The Language of Nature: Reconsidering the Mathematization of Science (Chapter 9), Kenneth Waters, Geoffery Gorham, Edward Slowik, Benjamin Hill (eds).