A Revised Taxonomy of the Iguanodont Dinosaur Genera and Species

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

JVP 26(3) September 2006—ABSTRACTS

Neoceti Symposium, Saturday 8:45 acid-prepared osteolepiforms Medoevia and Gogonasus has offered strong support for BODY SIZE AND CRYPTIC TROPHIC SEPARATION OF GENERALIZED Jarvik’s interpretation, but Eusthenopteron itself has not been reexamined in detail. PIERCE-FEEDING CETACEANS: THE ROLE OF FEEDING DIVERSITY DUR- Uncertainty has persisted about the relationship between the large endoskeletal “fenestra ING THE RISE OF THE NEOCETI endochoanalis” and the apparently much smaller choana, and about the occlusion of upper ADAM, Peter, Univ. of California, Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA; JETT, Kristin, Univ. of and lower jaw fangs relative to the choana. California, Davis, Davis, CA; OLSON, Joshua, Univ. of California, Los Angeles, Los A CT scan investigation of a large skull of Eusthenopteron, carried out in collaboration Angeles, CA with University of Texas and Parc de Miguasha, offers an opportunity to image and digital- Marine mammals with homodont dentition and relatively little specialization of the feeding ly “dissect” a complete three-dimensional snout region. We find that a choana is indeed apparatus are often categorized as generalist eaters of squid and fish. However, analyses of present, somewhat narrower but otherwise similar to that described by Jarvik. It does not many modern ecosystems reveal the importance of body size in determining trophic parti- receive the anterior coronoid fang, which bites mesial to the edge of the dermopalatine and tioning and diversity among predators. We established relationships between body sizes of is received by a pit in that bone. The fenestra endochoanalis is partly floored by the vomer extant cetaceans and their prey in order to infer prey size and potential trophic separation of and the dermopalatine, restricting the choana to the lateral part of the fenestra. -

And the Origin and Evolution of the Ankylosaur Pelvis

Pelvis of Gargoyleosaurus (Dinosauria: Ankylosauria) and the Origin and Evolution of the Ankylosaur Pelvis Kenneth Carpenter1,2*, Tony DiCroce3, Billy Kinneer3, Robert Simon4 1 Prehistoric Museum, Utah State University – Eastern, Price, Utah, United States of America, 2 Geology Section, University of Colorado Museum, Boulder, Colorado, United States of America, 3 Denver Museum of Nature and Science, Denver, Colorado, United States of America, 4 Dinosaur Safaris Inc., Ashland, Virginia, United States of America Abstract Discovery of a pelvis attributed to the Late Jurassic armor-plated dinosaur Gargoyleosaurus sheds new light on the origin of the peculiar non-vertical, broad, flaring pelvis of ankylosaurs. It further substantiates separation of the two ankylosaurs from the Morrison Formation of the western United States, Gargoyleosaurus and Mymoorapelta. Although horizontally oriented and lacking the medial curve of the preacetabular process seen in Mymoorapelta, the new ilium shows little of the lateral flaring seen in the pelvis of Cretaceous ankylosaurs. Comparison with the basal thyreophoran Scelidosaurus demonstrates that the ilium in ankylosaurs did not develop entirely by lateral rotation as is commonly believed. Rather, the preacetabular process rotated medially and ventrally and the postacetabular process rotated in opposition, i.e., lateral and ventrally. Thus, the dorsal surfaces of the preacetabular and postacetabular processes are not homologous. In contrast, a series of juvenile Stegosaurus ilia show that the postacetabular process rotated dorsally ontogenetically. Thus, the pelvis of the two major types of Thyreophora most likely developed independently. Examination of other ornithischians show that a non-vertical ilium had developed independently in several different lineages, including ceratopsids, pachycephalosaurs, and iguanodonts. -

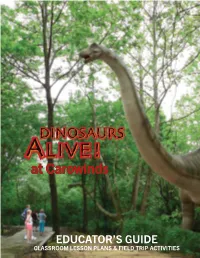

At Carowinds

at Carowinds EDUCATOR’S GUIDE CLASSROOM LESSON PLANS & FIELD TRIP ACTIVITIES Table of Contents at Carowinds Introduction The Field Trip ................................... 2 The Educator’s Guide ....................... 3 Field Trip Activity .................................. 4 Lesson Plans Lesson 1: Form and Function ........... 6 Lesson 2: Dinosaur Detectives ....... 10 Lesson 3: Mesozoic Math .............. 14 Lesson 4: Fossil Stories.................. 22 Games & Puzzles Crossword Puzzles ......................... 29 Logic Puzzles ................................. 32 Word Searches ............................... 37 Answer Keys ...................................... 39 Additional Resources © 2012 Dinosaurs Unearthed Recommended Reading ................. 44 All rights reserved. Except for educational fair use, no portion of this guide may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any Dinosaur Data ................................ 45 means—electronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, or any other without Discovering Dinosaurs .................... 52 explicit prior permission from Dinosaurs Unearthed. Multiple copies may only be made by or for the teacher for class use. Glossary .............................................. 54 Content co-created by TurnKey Education, Inc. and Dinosaurs Unearthed, 2012 Standards www.turnkeyeducation.net www.dinosaursunearthed.com Curriculum Standards .................... 59 Introduction The Field Trip From the time of the first exhibition unveiled in 1854 at the Crystal -

Diagnosis and Differentiation of the Order Primates

YEARBOOK OF PHYSICAL ANTHROPOLOGY 30:75-105 (1987) Diagnosis and Differentiation of the Order Primates FREDERICK S. SZALAY, ALFRED L. ROSENBERGER, AND MARIAN DAGOSTO Department of Anthropolog* Hunter College, City University of New York, New York, New York 10021 (F.S.S.); University of Illinois, Urbanq Illinois 61801 (A.L. R.1; School of Medicine, Johns Hopkins University/ Baltimore, h4D 21218 (M.B.) KEY WORDS Semiorders Paromomyiformes and Euprimates, Suborders Strepsirhini and Haplorhini, Semisuborder Anthropoidea, Cranioskeletal morphology, Adapidae, Omomyidae, Grades vs. monophyletic (paraphyletic or holophyletic) taxa ABSTRACT We contrast our approach to a phylogenetic diagnosis of the order Primates, and its various supraspecific taxa, with definitional proce- dures. The order, which we divide into the semiorders Paromomyiformes and Euprimates, is clearly diagnosable on the basis of well-corroborated informa- tion from the fossil record. Lists of derived features which we hypothesize to have been fixed in the first representative species of the Primates, Eupri- mates, Strepsirhini, Haplorhini, and Anthropoidea, are presented. Our clas- sification of the order includes both holophyletic and paraphyletic groups, depending on the nature of the available evidence. We discuss in detail the problematic evidence of the basicranium in Paleo- gene primates and present new evidence for the resolution of previously controversial interpretations. We renew and expand our emphasis on postcra- nial analysis of fossil and living primates to show the importance of under- standing their evolutionary morphology and subsequent to this their use for understanding taxon phylogeny. We reject the much advocated %ladograms first, phylogeny next, and scenario third” approach which maintains that biologically founded character analysis, i.e., functional-adaptive analysis and paleontology, is irrelevant to genealogy hypotheses. -

Camptosaurus Dispar Legs; Although, the Smaller Juveniles Might Have Been Able to Do So

Camptosaurus was too front heavy to walk on hind Camptosaurus dispar legs; although, the smaller juveniles might have been able to do so. e skull of Camptosaurus is about 15 inches long. It has no teeth at the front of the beak and broad crushing teeth in the cheeks. ese teeth are made stronger by ridges on the outer surface. Chewing causes these teeth to have a at, grinding surface. Unlike Allosaurus, these teeth cannot slice through esh, but they can pulverize vegetation. Our skeleton of Camptosaurus went on display Scienti c Name: Camptosaurus dispar at the museum around 1965 and was the Muse- Pronounced: KAMP-toe-SOR-us um’s second dinosaur skeleton. Originally, it was Name Meaning: Flexible lizard mounted in the kangaroo pose on its hind legs and Time Period: 147 Million Years Ago (MYA) Late using its tail as a prop. It was remounted into a new Jurassic four-legged pose in 2013 . e skeleton is 17¾ feet Length:16-23 feet (5-7 m) long long and 5 feet tall at the hips. It is a plaster of Paris Height: 3-4 feet (1 m) high at the hips cast of bones collected from the Cleveland Lloyd Weight: 2,200 pounds (1000 kg). Dinosaur Quarry, about 30 miles south of Price. Diet: Herbivore (plant eater) e pelvis is rather broad for its length and the Places Found: Camptosaurus was a distant relative of Iguanodon, upper bone, called the ilium, bows outwards. Discoverer: Marsh (1885) the dinosaur with the thumb-spike. In fact, the thumb (digit I) of Camptosaurus had little move- e hand of Camptosaurus has ve digits, but only ment and the claw was almost like a spike . -

A Phylogenetic Analysis of the Basal Ornithischia (Reptilia, Dinosauria)

A PHYLOGENETIC ANALYSIS OF THE BASAL ORNITHISCHIA (REPTILIA, DINOSAURIA) Marc Richard Spencer A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE December 2007 Committee: Margaret M. Yacobucci, Advisor Don C. Steinker Daniel M. Pavuk © 2007 Marc Richard Spencer All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Margaret M. Yacobucci, Advisor The placement of Lesothosaurus diagnosticus and the Heterodontosauridae within the Ornithischia has been problematic. Historically, Lesothosaurus has been regarded as a basal ornithischian dinosaur, the sister taxon to the Genasauria. Recent phylogenetic analyses, however, have placed Lesothosaurus as a more derived ornithischian within the Genasauria. The Fabrosauridae, of which Lesothosaurus was considered a member, has never been phylogenetically corroborated and has been considered a paraphyletic assemblage. Prior to recent phylogenetic analyses, the problematic Heterodontosauridae was placed within the Ornithopoda as the sister taxon to the Euornithopoda. The heterodontosaurids have also been considered as the basal member of the Cerapoda (Ornithopoda + Marginocephalia), the sister taxon to the Marginocephalia, and as the sister taxon to the Genasauria. To reevaluate the placement of these taxa, along with other basal ornithischians and more derived subclades, a phylogenetic analysis of 19 taxonomic units, including two outgroup taxa, was performed. Analysis of 97 characters and their associated character states culled, modified, and/or rescored from published literature based on published descriptions, produced four most parsimonious trees. Consistency and retention indices were calculated and a bootstrap analysis was performed to determine the relative support for the resultant phylogeny. The Ornithischia was recovered with Pisanosaurus as its basalmost member. -

Rule Booklet

Dig for fossils, build skeletons, and attract the most visitors to your museum! TM SCAN FOR VIDEO RULES AND MORE! FOSSILCANYON.COM Dinosaurs of North America edimentary rock formations of western North America are famous for the fossilized remains of dinosaurs The rules are simple enough for young players, but and other animals from the Triassic, Jurassic, and serious players can benefit Cretaceous periods of the Mesozoic Era. Your objective from keeping track of the cards that is to dig up fossils, build complete skeletons, and display have appeared, reasoning about them in your museum to attract as many visitors as possible. probabilities and expected returns, and choosing between aggressive Watch your museum’s popularity grow using jigsaw-puzzle and conservative plays. scoring that turns the competition into a race! GAME CONTENTS TM 200,000300,000 160,000 VISITORS VISITORS PER YEAR 140,000 VISITORS PER YEAR 180,000 VISITORS PER YEAR 400,000 VISITORS PER YEAR Dig for fossils, build skeletons, and 340,000 VISITORS PER YEAR RD COLOR ELETONS CA GENUS PERIODDIET SK FOSSIL VISITORSPARTS 360,000 VISITORS PER YEAR PER YEAR attract the most visitors to your museum! VISITORS PER YEAR PER YEAR Tyrannosaurus K C 1 4 500,000 Brachiosaurus J H 1 3 400,000 ON YOUR TURN: TM SCAN FOR VIDEO Triceratops K H 1 3 380,000 RULES AND MORE! Allosaurus J C 2 Dig3 a first360,000 card. If it is a fossil, keep it hidden. FOSSILCANYON.COM Ankylosaurus K H 2 If it3 is an340,000 action card, perform the action. -

Titanosauriform Teeth from the Cretaceous of Japan

“main” — 2011/2/10 — 15:59 — page 247 — #1 Anais da Academia Brasileira de Ciências (2011) 83(1): 247-265 (Annals of the Brazilian Academy of Sciences) Printed version ISSN 0001-3765 / Online version ISSN 1678-2690 www.scielo.br/aabc Titanosauriform teeth from the Cretaceous of Japan HARUO SAEGUSA1 and YUKIMITSU TOMIDA2 1Museum of Nature and Human Activities, Hyogo, Yayoigaoka 6, Sanda, 669-1546, Japan 2National Museum of Nature and Science, 3-23-1 Hyakunin-cho, Shinjuku-ku, Tokyo 169-0073, Japan Manuscript received on October 25, 2010; accepted for publication on January 7, 2011 ABSTRACT Sauropod teeth from six localities in Japan were reexamined. Basal titanosauriforms were present in Japan during the Early Cretaceous before Aptian, and there is the possibility that the Brachiosauridae may have been included. Basal titanosauriforms with peg-like teeth were present during the “mid” Cretaceous, while the Titanosauria with peg-like teeth was present during the middle of Late Cretaceous. Recent excavations of Cretaceous sauropods in Asia showed that multiple lineages of sauropods lived throughout the Cretaceous in Asia. Japanese fossil records of sauropods are conformable with this hypothesis. Key words: Sauropod, Titanosauriforms, tooth, Cretaceous, Japan. INTRODUCTION humerus from the Upper Cretaceous Miyako Group at Moshi, Iwaizumi Town, Iwate Pref. (Hasegawa et al. Although more than twenty four dinosaur fossil local- 1991), all other localities provided fossil teeth (Tomida ities have been known in Japan (Azuma and Tomida et al. 2001, Tomida and Tsumura 2006, Saegusa et al. 1998, Kobayashi et al. 2006, Saegusa et al. 2008, Ohara 2008, Azuma and Shibata 2010). -

A Juvenile Cf. Edmontosaurus Annectens (Ornithischia, Hadrosauridae) Femur Documents a Previously Unreported Intermediate Growth Stage for This Taxon Andrew A

Vertebrate Anatomy Morphology Palaeontology 7:59–67 59 ISSN 2292-1389 A juvenile cf. Edmontosaurus annectens (Ornithischia, Hadrosauridae) femur documents a previously unreported intermediate growth stage for this taxon Andrew A. Farke1,2,3,* and Eunice Yip2 1Raymond M. Alf Museum of Paleontology, 1175 West Baseline Road, Claremont, CA, 91711, USA 2The Webb Schools, 1175 West Baseline Road, Claremont, CA, 91711, USA 3Dinosaur Institute, Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, 900 Exposition Blvd. Los Angeles, CA, 90007, USA; [email protected] Abstract: A nearly complete, but isolated, femur of a small hadrosaurid from the Hell Creek Formation of Montana is tentatively referred to Edmontosaurus annectens. At 28 cm long, the element can be classified as likely that from an ‘early juvenile’ individual, approximately 24% of the maximum known femur length for this species. Specimens from this size range and age class have not been described previously for E. annectens. Notable trends with increasing body size include increasingly distinct separation of the femoral head and greater trochanter, relative increase in the size of the cranial trochanter, a slight reduction in the relative breadth of the fourth trochanter, and a relative increase in the prominence of the cranial intercondylar groove. The gross profile of the femoral shaft is fairly consistent between the smallest and largest individuals. Although an ontogenetic change from relatively symmetrical to an asymmetrical shape in the fourth trochanter has been suggested previously, the new juvenile specimen shows an asymmetric fourth tro- chanter. Thus, there may not be a consistent ontogenetic pattern in trochanteric morphology. An isometric relationship between femoral circumference and femoral length is confirmed for Edmontosaurus. -

Implications for Predatory Dinosaur Macroecology and Ontogeny in Later Late Cretaceous Asiamerica

Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences Theropod Guild Structure and the Tyrannosaurid Niche Assimilation Hypothesis: Implications for Predatory Dinosaur Macroecology and Ontogeny in later Late Cretaceous Asiamerica Journal: Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences Manuscript ID cjes-2020-0174.R1 Manuscript Type: Article Date Submitted by the 04-Jan-2021 Author: Complete List of Authors: Holtz, Thomas; University of Maryland at College Park, Department of Geology; NationalDraft Museum of Natural History, Department of Geology Keyword: Dinosaur, Ontogeny, Theropod, Paleocology, Mesozoic, Tyrannosauridae Is the invited manuscript for consideration in a Special Tribute to Dale Russell Issue? : © The Author(s) or their Institution(s) Page 1 of 91 Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences 1 Theropod Guild Structure and the Tyrannosaurid Niche Assimilation Hypothesis: 2 Implications for Predatory Dinosaur Macroecology and Ontogeny in later Late Cretaceous 3 Asiamerica 4 5 6 Thomas R. Holtz, Jr. 7 8 Department of Geology, University of Maryland, College Park, MD 20742 USA 9 Department of Paleobiology, National Museum of Natural History, Washington, DC 20013 USA 10 Email address: [email protected] 11 ORCID: 0000-0002-2906-4900 Draft 12 13 Thomas R. Holtz, Jr. 14 Department of Geology 15 8000 Regents Drive 16 University of Maryland 17 College Park, MD 20742 18 USA 19 Phone: 1-301-405-4084 20 Fax: 1-301-314-9661 21 Email address: [email protected] 22 23 1 © The Author(s) or their Institution(s) Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences Page 2 of 91 24 ABSTRACT 25 Well-sampled dinosaur communities from the Jurassic through the early Late Cretaceous show 26 greater taxonomic diversity among larger (>50kg) theropod taxa than communities of the 27 Campano-Maastrichtian, particularly to those of eastern/central Asia and Laramidia. -

Discovering Paleontology: Dinosaurs, Ice Age Mammals, Fossils & More Hints for Teachers Upper Elementary

Amherst College Discovering Paleontology: Dinosaurs, Ice Age Mammals, Fossils & More Hints for Teachers Upper Elementary MUSEUM INFORMATION: The “Discovering Paleontology” activity guide is designed for students to practice scientific inquiry to be used in the Beneski Museum of Natural History in conjunction with the classroom curriculum; however, it can also be used independently. • The Beneski Museum of Natural History displays the fossil remains of many different creatures throughout different periods of time. • While exploring the exhibition, encourage your students to look above their heads to see specimens displayed at different levels of the museum. • The Beneski Museum of Natural History can accommodate up to 45 children and chaperones at a time. Please consider splitting into smaller sub-groups when completing the activity. • When your students arrive at the museum, they will be given a brief greeting by a museum staff member. After this greeting is a good time for you to talk to your students and chaperones about the “Discovering Paleontology” activity. PREPARING AN ACTIVITY: • The museum does NOT provide copies of the “Discovering Paleontology” activity guide. Please prepare copies for your students. • The “Discovering Paleontology” activity guide asks students to look critically at specimens and use their skills in scientific inquiry to hypothesize and visualize extinct creatures of different time periods of Earth’s past. Students will learn about vertebrates, classifications, extinction, and physical characteristics as well as hypothesize how Ice age mammals evolved into the animals they are today. Students will examine fossilized evidence of these creatures, and learn about the many different minerals that make up our world today. -

Phylogeny and Biogeography of Iguanodontian Dinosaurs, with Implications from Ontogeny and an Examination of the Function of the Fused Carpal-Digit I Complex

Phylogeny and Biogeography of Iguanodontian Dinosaurs, with Implications from Ontogeny and an Examination of the Function of the Fused Carpal-Digit I Complex By Karen E. Poole B.A. in Geology, May 2004, University of Pennsylvania M.A. in Earth and Planetary Sciences, August 2008, Washington University in St. Louis A Dissertation submitted to The Faculty of The Columbian College of Arts and Sciences of The George Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 31, 2015 Dissertation Directed by Catherine Forster Professor of Biology The Columbian College of Arts and Sciences of The George Washington University certifies that Karen Poole has passed the Final Examination for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy as of August 10th, 2015. This is the final and approved form of the dissertation. Phylogeny and Biogeography of Iguanodontian Dinosaurs, with Implications from Ontogeny and an Examination of the Function of the Fused Carpal-Digit I Complex Karen E. Poole Dissertation Research Committee: Catherine A. Forster, Professor of Biology, Dissertation Director James M. Clark, Ronald Weintraub Professor of Biology, Committee Member R. Alexander Pyron, Robert F. Griggs Assistant Professor of Biology, Committee Member ii © Copyright 2015 by Karen Poole All rights reserved iii Dedication To Joseph Theis, for his unending support, and for always reminding me what matters most in life. To my parents, who have always encouraged me to pursue my dreams, even those they didn’t understand. iv Acknowledgements First, a heartfelt thank you is due to my advisor, Cathy Forster, for giving me free reign in this dissertation, but always providing valuable commentary on any piece of writing I sent her, no matter how messy.