Minimally Invasive Transhiatal Esophagectomy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Management of Specific Wounds

7 Management of Specific Wounds Bite Wounds 174 Hygroma 234 Burns 183 Snakebite 239 Inhalation Injuries 195 Brown Recluse Spider Bites 240 Chemical Burns 196 Porcupine Quills 240 Electrical Injuries 197 Lower Extremity Shearing Wounds 243 Radiation Injuries 201 Plate 10: Pipe Insulation Protective Frostbite 204 Device: Elbow 248 Projectile Injuries 205 Plate 11: Pipe Insulation to Protect Explosive Munitions: Ballistic, the Greater Trochanter 250 Blast, and Thermal Injuries 227 Plate 12: Vacuum Drain Impalement Injuries 227 Management of Elbow Pressure Ulcers 228 Hygromas 252 Atlas of Small Animal Wound Management and Reconstructive Surgery, Fourth Edition. Michael M. Pavletic. © 2018 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Published 2018 by John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Companion website: www.wiley.com/go/pavletic/atlas 173 174 Atlas of Small Animal Wound Management and Reconstructive Surgery BITE WOUNDS to the skin. Wounds may be covered by a thick hair coat and go unrecognized. The skin and underlying Introduction issues can be lacerated, stretched, crushed, and avulsed. Circulatory compromise from the division of vessels and compromise to collateral vascular channels can result in Bite wounds are among the most serious injuries seen in massive tissue necrosis. It may take several days before small animal practice, and can account for 10–15% of all the severity of tissue loss becomes evident. All bites veterinary trauma cases. The canine teeth are designed are considered contaminated wounds: the presence of for tissue penetration, the incisors for grasping, and the bacteria in the face of vascular compromise can precipi- molars/premolars for shearing tissue. The curved canine tate massive infection. teeth of large dogs are capable of deep penetration, whereas the smaller, straighter canine teeth of domestic cats can penetrate directly into tissues, leaving a rela- tively small cutaneous hole. -

Reconstructive

RECONSTRUCTIVE Muscle versus Nonmuscle Flaps in the Reconstruction of Chronic Osteomyelitis Defects Christopher J. Salgado, Background: Surgical treatment of chronic osteomyelitis requires aggressive M.D. debridement followed by wound coverage and obliteration of dead space with Samir Mardini, M.D. vascularized tissue. Controversy remains as to the effectiveness of different tissue Amir A. Jamali, M.D. types in achieving these goals and in the eradication of disease. Juan Ortiz, M.D. Methods: Chronic osteomyelitis was induced in 26 goat tibias using Staphylo- Raoul Gonzales, D.V.M., coccus aureus as an infecting inoculum. In a single stage, debridement followed Ph.D. by reconstruction using either a muscle flap (n ϭ 13) or a fasciocutaneous flap Hung-Chi Chen, M.D. (n ϭ 13) was performed. Flap donor sites were closed primarily and antibiotics El Paso, Texas; Kaohsiung, Taiwan; were given for 5 days postoperatively. Daily clinical evaluation for 1 year was and Sacramento, Calif. performed and monthly radiographs were obtained for 9 months and 1 year after the reconstruction. Results: Twenty-five flaps survived completely, and one nonmuscle flap under- went partial flap loss following a period of venous congestion. There were no postoperative complications in the muscle flap group. Two goats (15 percent) in the nonmuscle group developed superficial wounds in the immediate post- operative period that resolved with conservative management. No limbs had recurrent osteomyelitis wounds at 1 year of clinical follow-up examination. Radiographic evidence of osteomyelitis was present in two goats (15 percent) in the muscle group and one goat (8 percent) in the nonmuscle group. -

(TECA) Surgery

Audit of Total Ear Canal Ablation-Lateral Bulla Osteotomy Procedures Performed by One Surgeon Audit project lead: D G Bentley Subject/area of practice: Surgery/Dermatology Date: January 2nd 2018 Reasons for Audit: To determine how complication rate of this procedure, both short and long term, compare with that in recently published literature and to be sure this procedure should be still be offered in-house rather than being referred to a surgical specialist. Background Total Ear Canal Ablation-Lateral Bulla Osteotomy (TECA-LBO) procedures on dogs (and cats) have been performed by this surgeon since 1991 and since that time over 260 procedures have been performed. The surgeon also runs a dermatology service with special interest in ear disease and wishes to provide a complete service whereby cases that are beyond medical treatment can go to surgery without being referred to a specialist surgeon. Indications for TECA-LBO are “end stage otitis”, where there is chronic irreversible change to the ear canal, intractable ear infections particularly as a result of middle ear infection and changes in the vicinity of the tympanic membrane/lower horizontal ear canal, and tumours in the ear canal which cannot be dealt with either by Lateral Wall Resection or Vertical Canal Ablation. Also sometimes, due to financial reasons, a client may prefer surgery to lengthy courses of treatment, requiring several anaesthetics and ear flushings, with no guarantee of success at the outset. The surgeon first learnt the technique that was published in video format in the “In Practice” series around 1991. This involved the use of an osteotome to separate the ear canal from the bulla and also looking for the facial nerve and pulling it out of the way using penrose drain material. -

228 April 2003 Category 1

Laparoscopica cantireflux Edward T Chory, MD Tracey A Ross, CST, MEd surgery astroesophageal Reflux The number of undiagnosed cases Disease (GERD) is a com- promises to be much higher based mon condition with a on the millions of heartburn suf- heavy economic impact. In ferers who take over-the- G a study published in the counter medications to treat May 2002 issue of Gastroenterol- their symptoms. GERD is also the ogy, researchers calculated that most expensive of the digestive GERD is one of the most preva- conditions with annual direct lent digestive diseases in America costs at $9.3 billion.1 with 19 million diagnosed cases.1 APRIL 2003 The Surgical Technologist 13 228 APRIL 2003 CATEGORY 1 Indirect costs, such as missed work and lower (painful swallowing), esophageal spasm, and productivity, would be almost impossible to more rarely GI bleeding (hematemesis or mele- measure accurately. However, companies and na). Tertiary symptoms are unrelated to the individuals are likely to feel the financial impact esophagus, such as reflux-induced asthma, in increased insurance premiums. For example, hoarseness and pharyngitis. Tertiary symptoms in 2002, the Wall Street Journal reported that the have increasingly been considered indications cost of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) increased for antireflux surgery, and recent reports have General Motors’ health care budget for employ- documented excellent results, particularly for ees and retirees more than $55 million.2 reflux-induced asthma.11 With increasing experience in laparoscopic Traditionally, antireflux surgery was reserved antireflux surgery over the last 10 years, mor- for patients who did not respond to medical bidity has decreased, outcomes have improved therapy. -

Answer Key Chapter 1

Instructor's Guide AC210610: Basic CPT/HCPCS Exercises Page 1 of 101 Answer Key Chapter 1 Introduction to Clinical Coding 1.1: Self-Assessment Exercise 1. The patient is seen as an outpatient for a bilateral mammogram. CPT Code: 77055-50 Note that the description for code 77055 is for a unilateral (one side) mammogram. 77056 is the correct code for a bilateral mammogram. Use of modifier -50 for bilateral is not appropriate when CPT code descriptions differentiate between unilateral and bilateral. 2. Physician performs a closed manipulation of a medial malleolus fracture—left ankle. CPT Code: 27766-LT The code represents an open treatment of the fracture, but the physician performed a closed manipulation. Correct code: 27762-LT 3. Surgeon performs a cystourethroscopy with dilation of a urethral stricture. CPT Code: 52341 The documentation states that it was a urethral stricture, but the CPT code identifies treatment of ureteral stricture. Correct code: 52281 4. The operative report states that the physician performed Strabismus surgery, requiring resection of the medial rectus muscle. CPT Code: 67314 The CPT code selection is for resection of one vertical muscle, but the medial rectus muscle is horizontal. Correct code: 67311 5. The chiropractor documents that he performed osteopathic manipulation on the neck and back (lumbar/thoracic). CPT Code: 98925 Note in the paragraph before code 98925, the body regions are identified. The neck would be the cervical region; the thoracic and lumbar regions are identified separately. Therefore, three body regions are identified. Correct code: 98926 Instructor's Guide AC210610: Basic CPT/HCPCS Exercises Page 2 of 101 6. -

Cardinal Health™ Jackson-Pratt® Wound Drain Offerings

Cardinal Health™ Jackson-Pratt® Wound drain offerings Delivering confidence in product performance, with a commitment to patient comfort and safety. Cardinal Health™ Jackson-Pratt® The name you trust for wound drainage products. Nearly 50 A standardized years of A commitment portfolio to product legacy, to patient safety accommodate credibility and and comfort every need innovation What’s inside Introduction _____________________________ 3 Jackson-Pratt® Perforated Drains _________ 4-5 Jackson-Pratt® Channel Drains ____________ 6-7 Jackson-Pratt® Hemaduct® Wound Drains __________________________ 8-9 Cardinal Health™ Penrose Drains _________10 -11 Jackson-Pratt® Bulb Reservoirs and Accessories________________________12-13 Jackson-Pratt® 3-Spring Reservoirs and Accessories__________________________ 14 Argyle® Saratoga Drains __________________ 15 2 Cardinal Health™ Jackson-Pratt® Wound Drain catalog To order call: 800.227.3462 Cardinal Health™ Jackson-Pratt® Wound Drains Providing products to help improve patient safety and comfort is at the heart of what we do. For years, our quality, clinically designed Jackson-Pratt® Wound Drains have been supported with best practice guidance to help ensure that clinicians, too, feel comfortable and ultimately more confident in what they do. Our Jackson-Pratt® Wound Drain line, trusted amongst the clinical community since 1971 and a pillar of our extensive drainage offerings, represents our long- standing experience in the industry. You will find comfort in knowing that we provide a full assortment of wound drains and drainage systems, with an opportunity to standardize, ensuring that your wound drain portfolio will effectively meet the needs of a variety of situations and procedures. The Cardinal Health Wound Drain team is committed to helping provide solutions for more positive patient outcomes. -

Atlas of Surgical Techniques for the Upper Gastrointestinal Tract and Small Bowel

Atlas of Surgical Techniques for the Upper Gastrointestinal Tract and Small Bowel A Volume in the Surgical Techniques Atlas Series Michael J. Rosen, MD Chief, Division of Gastrointestinal and General Surgery Director, Case Comprehensive Hernia Center Assistant Professor, Case Medical Center, University Hospitals of Cleveland, Cleveland, Ohio Jeffrey R. Ponsky, MD Chairman, Department of Surgery, Case Medical Center, University Hospitals of Cleveland, Cleveland, Ohio Series Editors: Courtney M. Townsend Jr., MD Professor and John Woods Harris Distinguished Chairman, Department of Surgery, The University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston, Texas B. Mark Evers, MD Director, Lucille P. Markey Cancer Center Professor and Vice-Chair for Research, UK Department of Surgery, Markey Cancer Center Director Chair, Physician-in-Chief, Oncology Service Line, University of Kentucky, Markey Cancer Center, Lexington, Kentucky Copyright © 2010 by Saunders, an imprint of Elsevier Inc. Atlas of Surgical Techniques for the Upper GI Tract and Small Bowel - A Volume in the Surgical Techniques Atlas Series By Jeffrey Ponsky, MD and Michael Rosen, MD Key Features x Provides step-by-step guidance on a wide range of procedures, both open and interventional, giving you multiple options for approaching any challenge. x Examines the hottest topics in upper gastrointestinal and small bowel surgery. x Discusses pearls and pitfalls to help you avoid complications. x Presents more than 300 full-color illustrations and step-by-step intraoperative photographs for expert visual guidance. x Offers pre- and postoperative imaging studies that show the outcomes of various conditions following surgery. x Uses a consistent, easy-to-follow chapter format that includes clinical anatomy, pre-operative considerations, operative steps, post-operative care, and pearls and pitfalls to make reference easy. -

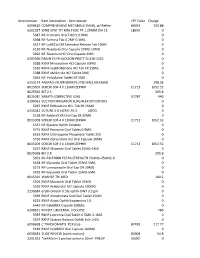

Item Master CPT Code Charge 6090610 COMPREHENSIVE

Item Number Item Description - Item Master CPT Code Charge 6090610 COMPREHENSIVE METABOLIC PANEL w/ Reflex- 80053 103.88 6202327 WIRE SYNT TIT KIRS TROC PT 1.25MM DIA 15 L8699 0 5387 NF-Premarin Oral Tablet 0.9MG 0 5398 NF-Falmina Tab 0.2MF-0.1MG 0 5517 NF-LaMICtal XR Extended Release Tab 100M 0 6130 NF-Nuedexta Oral Capsule 20MG-10MG 0 5992 NF-Terazosin HCl Oral Capsule 2MG 0 6203390 DRAIN 19 FR JACKSON-PRATT SU130-1325 0 5288 RXNF Minocycline HCl Capsule 50MG 0 5310 RXNF oxyMORphone HCl Tab ER 15MG 0 5388 RXNF aMILoride HCl Tablet 5MG 0 5564 NF- Felodipine Tablet ER 5MG 0 6213174 ANSPACH BURR 6MM FLUTED BALL MIA166B 298.36 8015007 SCREW SOF 4 X 11MM ZEPHIR C1713 1052.52 8025916 BIT 2.3 205.8 8026081 SA6AT5 CORRECTIVE LENS V2787 440 6200062 SUCTION IRRIGATOR SURGIFLEX 007200-903 0 5287 RXNF PARoxetine HCL Tab ER 25MG 0 6215042 SUTURE 3-0 VICRYL PS-2 J497G 0 6138 NF-Adderall XR Oral Cap ER 30MG 0 8015008 SCREW SOF 4 X 13MM ZEPHIR C1713 1052.52 5337 NF-Systane Ophth Solution 0 3774 RXNF Premarin Oral Tablet 0.9MG 0 6162 RXNF Chloroquine Phosphate Tablet 250 0 5756 RXNF Ziprasidone HCl Oral Capsule 20MG 0 8015009 SCREW SOF 4 X 15MM ZEPHIR C1713 1052.52 5427 RXNF Glyxambi Oral Tablet 25MG-5MG 0 8025918 BIT 2.5 205.8 5959 NF-EXCEDRIN EXTRA STRENGTH 250MG-250MG-6 0 5428 NF-Glyxambi Oral Tablet 25MG-5MG 0 5273 NF-Lansoprazole Oral Cap DR 30MG 0 5429 NF-Glyxambi Oral Tablet 25MG-5MG 0 8015391 WASHER TRI MED 180.2 5504 RXNF Movantik Oral Tablet 25MG 0 5336 RXNF Acebutolol HCl Capsule 200MG 0 2290384 erythromycin 0.5% ophth OINT 3.5 gm 0 5399 RXNF -

Browne Deltoid Retractor

Introduction Since 1826, physicians and Statement of Policy surgeons have depended on George Tiemann & Co., has manufactured fine surgical instruments since 1826. Since then, we have supplied the George Tiemann & Co. medical profession with high quality, correctly styled products. In addition to our own products, we represent other manufacturers and importers, and therefore welcome inquiries concerning instruments not shown in our catalog. While we feel that the patterns shown are the most widely used and accepted, occasionally another sytle may be preferred. In this event, we can usually supply the instrument if either a catalog number, sample or description can be provided. Returns for credit can be made without permission. However, this must be done within 30 days from date of billing. Items are subject to a restocking fee if they are not in original packaging material, or, have been autoclaved/sterilized. Instruments older than 30 days require approval and are also subject to restocking charges. When returning items, please provide the original invoice number, your order number (if any) and other pertinent information. Claims for shortages must be made within 5 days of package New surgical procedures, improved techniques, receipt. To avoid short shipments, all orders are computer refinements in tooling skills and advancements weighed and double checked for accuracy by two separate in metallurgy, emphasize the continuing need individuals. for change. We reserve the right to ship the most current models, which will always Ordering Information reflect the wishes of the medical profession. 1) Please use catalog number and supply size, style and quantity. Some catalog numbers cover more than one size or style. -

ASAIO 2018 Annual Meeting Abstracts. Washington, DC

May-June 2018 • Volume 64 • Supplement 1 www.asaiojournal.com ISSN 1058-2916 05/21/2018 on BhDMf5ePHKav1zEoum1tQfN4a+kJLhEZgbsIHo4XMi0hCywCX1AWnYQp/IlQrHD3be73+7zLk/Sq+y6koaZl6Ep8oGuop87+8AoBvh7J400mYizg71tReg== by https://journals.lww.com/asaiojournal from Downloaded Downloaded from https://journals.lww.com/asaiojournal by BhDMf5ePHKav1zEoum1tQfN4a+kJLhEZgbsIHo4XMi0hCywCX1AWnYQp/IlQrHD3be73+7zLk/Sq+y6koaZl6Ep8oGuop87+8AoBvh7J400mYizg71tReg== The Official Publication of the American Society for Artificial Internal Organs ASAIO Promotes the Development, Application, and Awareness of Organ Technologies that Enhance Quality and Duration of Life Washington, DC ASAIO 64th Annual Conference June 13-16, 2018 on 05/21/2018 ASAIO 2018 Annual Meeting Abstracts. Published for the Society by May/June 2018 Volume 64 • Supplement 1 ISSN 1058-2916 Bioengineering Abstracts .....................................................................................Pages 1-39 Cardiac Abstracts ............................................................................................Pages 40-101 Nursing Circ-Support Abstracts .....................................................................Pages 102-113 Pediatric Abstracts ........................................................................................Pages 114-122 Pulmonary Abstracts .....................................................................................Pages 123-130 Renal Abstracts .............................................................................................Pages 131-134 -

Surgery and Healing in the Developing World

Surgery and Healing in the Developing World Glenn W. Geelhoed, M.D., FACS Professor of Surgery Professor of International Medical Education Professor of Microbiology and Tropical Medicine George Washington University Medical Center Washington, D.C., U.S.A. L A N D E S B I O S C I E N C E GEORGETOWN, TEXAS U.S.A. Surgery and Healing in the Developing World LANDES BIOSCIENCE Georgetown, Texas U.S.A. 2005 Landes Bioscience Printed in the U.S.A. Please address all inquiries to the Publisher: Landes Bioscience, 810 S. Church Street, Georgetown, Texas, U.S.A. 78626 Phone: 512/ 863 7762; FAX: 512/ 863 0081 While the authors, editors, sponsor and publisher believe that drug selection and dosage and the specifications and usage of equipment and devices, as set forth in this book, are in accord with current recommendations and practice at the time of publication, they make no warranty, expressed or implied, with respect to material described in this book. In view of the ongoing research, equipment development, changes in governmental regulations and the rapid accumulation of information relating to the biomedical sciences, the reader is urged to carefully review and evaluate the information provided herein. Contents Foreword .......................................................................... ix Preface.............................................................................. xi 1. Preparation Time .............................................................. 1 Harvey Bratt 2. Surgery in Developing Countries ...................................... 6 John E. Woods 3. A Commitment to Voluntary Health Care Service .......... 13 Donald C. Mullen 4. International Surgical Education: The Perspective from Several Continents ........................ 18 Glenn W. Geelhoed 5. Medicine Writ Large in the Raw, without Power or Plumbing ............................................ 25 Glenn W. -

Abo Grouping 60 (P) Abslut Cd4 & Cd8 Ct W/Rato

Procedure description Charge (P) METHODONE 80 (P) ABO 60 (P) ABO GROUPING 60 (P) ABSLUT CD4 & CD8 CT W/RATO 140 (P) ACHR BINDING AB 148 (P) ACHR BLOCKING AB 148 (P) ADH 131 (P) AEROBIC CULTURE 132 (P) ALBUMIN, SERUM 56 (P) AMPHETAMINES 8 (P) AMPHETAMINES 80 (P) ANA 36 (P) ANTI - SSA 143 (P) ANTI - SSB 143 (P) ANTI CENTROMERE B 39 (P) ANTI CHROMATIN AB 35 (P) ANTI DS DNA 41 (P) ANTI HISTONE 39 (P) ANTI Jo-1 39 (P) ANTI RNP 39 (P) ANTI RNP SLP AB 39 (P) ANTI Scl-70 39 (P) ANTI SM 39 (P) ANTI SM SLP AB 39 (P) ANTI-DNA (DS) Ab Qn 41 (P) ANTI-GROUP B STREPTOCOCCUS 104 (P) ANTI-H INFLUENZA TYPE B 104 (P) ANTI-N MENINGITIS A/Y 104 (P) ANTI-N MENINGITIS C/W 135 104 (P) ANTI-STREP PNEUMONIA 104 (P) ANTI-THYROGLOBULIN AB 194 (P) ANTI-THYROID MICROSOMAL AB 192 (P) ANTIBODY SCREEN 109 (P) ANTICARDIOLYPIN AB IGA 58 (P) ANTICARDIOLYPIN AB IGG 58 (P) ANTICARDIOLYPIN AB IGM 58 (P) ANTIGEN TYPING,C 74 (P) ANTIGEN TYPING,c 74 (P) ANTIGEN TYPING,E 74 (P) ANTIGEN TYPING,e 74 (P) ANTIGEN TYPING,M 74 (P) ANTIGEN TYPING,N 74 (P) ANTIGEN TYPING,S 74 (P) ANTIGEN TYPING,s 74 (P) ARSENIC, BLOOD 87 (P) ARSENIC, URINE 90 (P) B. HENSELAE IGG 55 (P) B. HENSELAE IGM 55 (P) B. QUINTANA IGG 55 (P) B. QUINTANA IGM 55 (P) BARBITURATES 8 (P) BARBITURATES 80 (P) BEEF 52 (P) BENZODIAZEPINES 8 (P) BENZODIAZEPINES 80 (P) BETA 2 GLYCO IGA 65 (P) BETA 2 GLYCO IGG 65 (P) BETA 2 GLYCO IGM 65 (P) BLEEDING TIME, IVY 52 (P) BLOOD GASES 158 (P) BONE MARROW/BLOOD CULTURE 480 (P) Bordetella pertussis DNA 90 (P) BRUCELLA ABORTUS 70 (P) BRUCELLA IGG 39 (P) BRUCELLA IGM 39 (P) BUFFY COAT PREP 70 (P) BV A.