Proposal to Encode the Divehi Script in Unicode

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Dhivehi Language. a Descriptive and Historical Grammar of Maldivian and Its Dialects“ Von Sonja Fritz (2002)

Achtung! Dies ist eine Internet-Sonderausgabe des Buchs „The Dhivehi Language. A Descriptive and Historical Grammar of Maldivian and Its Dialects“ von Sonja Fritz (2002). Sie sollte nicht zitiert werden. Zitate sind der Originalausgabe zu entnehmen, die als Beiträge zur Südasienforschung, 191 erschienen ist (Würzburg: Ergon Verlag 2002 / Heidelberg: Südasien-Institut). Attention! This is a special internet edition of the book “ The Dhivehi Language. A Descriptive and Historical Grammar of Maldivian and Its Dialects ” by Sonja Fritz (2002). It should not be quoted as such. For quotations, please refer to the original edition which appeared as Beiträge zur Südasienforschung, 191 (Würzburg: Ergon Verlag 2002 / Heidelberg: Südasien-Institut). Alle Rechte vorbehalten / All rights reserved: Sonja Fritz, Frankfurt 2012 37 The Dhivehi Language A Descriptive and Historical Grammar of Maldivian and Its Dialects by Sonja Fritz Heidelberg 2002 For Jost in love Preface This book represents a revised and enlarged English version of my habilitation thesis “Deskriptive Grammatik des Maledivischen (Dhivehi) und seiner Dialekte unter Berücksichtigung der sprachhistorischen Entwicklung” which I delivered in Heidelberg, 1997. I started my work on Dhivehi (Maldivian) in 1988 when I had the opportunity to make some tape recordings with native speakers during a private stay in the Maldives. Shortly after, when I became aware of the fact that there were almost no preliminary studies of a scientific character on the Maldivian language and literature and, particularly, no systematic linguistic studies at all, I started to collect material for an extensive grammatical description of the Dhivehi language. In 1992, I went to the Maldives again in order to continue my work with informants and to make official contact with the corresponding institutions in M¯ale, whom I asked to help me in planning my future field research. -

International Relations and Organisations June 2017 to January 2018

Insights PT 2018 Exclusive International Relations and Organisations June 2017 to January 2018 WWW. INSIGHTSONINDIA . COM Insights PT 2018 Exclusive (International Relations) Table of Contents Bilateral Relations ............................................................................................................. 7 India – China ...................................................................................................................... 7 1. Doklam Dispute .............................................................................................................................. 7 2. India, China ‘clash’ near high-altitude Pangong Lake ........................................................................ 7 3. India – China Trade Deficit ............................................................................................................... 8 India – U.S ......................................................................................................................... 8 1. India major defence partner: U.S. .................................................................................................... 8 2. US House passes Bill for strengthening defence ties with India ........................................................ 9 3. US rolls out expedited entry for ‘low-risk’ Indian travellers .............................................................. 9 4. US- India Strategic Partnership Forum (USISPF) ............................................................................... 9 5. India, US -

*‡Table 5. Ethnic and National Groups

T5 Table[5.[Ethnic[and[National[Groups T5 T5 TableT5[5. [DeweyEthnici[Decimaand[NationalliClassification[Groups T5 *‡Table 5. Ethnic and National Groups The following numbers are never used alone, but may be used as required (either directly when so noted or through the interposition of notation 089 from Table 1) with any number from the schedules, e.g., civil and political rights (323.11) of Navajo Indians (—9726 in this table): 323.119726; ceramic arts (738) of Jews (—924 in this table): 738.089924. They may also be used when so noted with numbers from other tables, e.g., notation 174 from Table 2 In this table racial groups are mentioned in connection with a few broad ethnic groupings, e.g., a note to class Blacks of African origin at —96 Africans and people of African descent. Concepts of race vary. A work that emphasizes race should be classed with the ethnic group that most closely matches the concept of race described in the work Except where instructed otherwise, and unless it is redundant, add 0 to the number from this table and to the result add notation 1 or 3–9 from Table 2 for area in which a group is or was located, e.g., Germans in Brazil —31081, but Germans in Germany —31; Jews in Germany or Jews from Germany —924043. If notation from Table 2 is not added, use 00 for standard subdivisions; see below for complete instructions on using standard subdivisions Notation from Table 2 may be added if the number in Table 5 is limited to speakers of only one language even if the group discussed does not approximate the whole of the -

Assessment of Options for Handling Full Unicode Character Encodings in MARC21 a Study for the Library of Congress

1 Assessment of Options for Handling Full Unicode Character Encodings in MARC21 A Study for the Library of Congress Part 1: New Scripts Jack Cain Senior Consultant Trylus Computing, Toronto 1 Purpose This assessment intends to study the issues and make recommendations on the possible expansion of the character set repertoire for bibliographic records in MARC21 format. 1.1 “Encoding Scheme” vs. “Repertoire” An encoding scheme contains codes by which characters are represented in computer memory. These codes are organized according to a certain methodology called an encoding scheme. The list of all characters so encoded is referred to as the “repertoire” of characters in the given encoding schemes. For example, ASCII is one encoding scheme, perhaps the one best known to the average non-technical person in North America. “A”, “B”, & “C” are three characters in the repertoire of this encoding scheme. These three characters are assigned encodings 41, 42 & 43 in ASCII (expressed here in hexadecimal). 1.2 MARC8 "MARC8" is the term commonly used to refer both to the encoding scheme and its repertoire as used in MARC records up to 1998. The ‘8’ refers to the fact that, unlike Unicode which is a multi-byte per character code set, the MARC8 encoding scheme is principally made up of multiple one byte tables in which each character is encoded using a single 8 bit byte. (It also includes the EACC set which actually uses fixed length 3 bytes per character.) (For details on MARC8 and its specifications see: http://www.loc.gov/marc/.) MARC8 was introduced around 1968 and was initially limited to essentially Latin script only. -

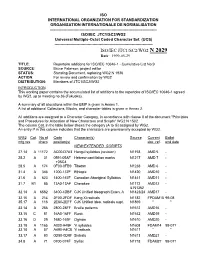

ISO/IEC JTC1/SC2/WG2 N 2029 Date: 1999-05-29

ISO INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATION FOR STANDARDIZATION ORGANISATION INTERNATIONALE DE NORMALISATION --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ISO/IEC JTC1/SC2/WG2 Universal Multiple-Octet Coded Character Set (UCS) -------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ISO/IEC JTC1/SC2/WG2 N 2029 Date: 1999-05-29 TITLE: Repertoire additions for ISO/IEC 10646-1 - Cumulative List No.9 SOURCE: Bruce Paterson, project editor STATUS: Standing Document, replacing WG2 N 1936 ACTION: For review and confirmation by WG2 DISTRIBUTION: Members of JTC1/SC2/WG2 INTRODUCTION This working paper contains the accumulated list of additions to the repertoire of ISO/IEC 10646-1 agreed by WG2, up to meeting no.36 (Fukuoka). A summary of all allocations within the BMP is given in Annex 1. A list of additional Collections, Blocks, and character tables is given in Annex 2. All additions are assigned to a Character Category, in accordance with clause II of the document "Principles and Procedures for Allocation of New Characters and Scripts" WG2 N 1502. The column Cat. in the table below shows the category (A to G) assigned by WG2. An entry P in this column indicates that the characters are provisionally accepted by WG2. WG2 Cat. No of Code Character(s) Source Current Ballot mtg.res chars position(s) doc. ref. end date NEW/EXTENDED SCRIPTS 27.14 A 11172 AC00-D7A3 Hangul syllables (revision) N1158 AMD 5 - 28.2 A 31 0591-05AF Hebrew cantillation marks N1217 AMD 7 - +05C4 28.5 A 174 0F00-0FB9 Tibetan N1238 AMD 6 - 31.4 A 346 1200-137F Ethiopic N1420 AMD10 - 31.6 A 623 1400-167F Canadian Aboriginal Syllabics N1441 AMD11 - 31.7 B1 85 13A0-13AF Cherokee N1172 AMD12 - & N1362 32.14 A 6582 3400-4DBF CJK Unified Ideograph Exten. -

1 Working Draft for Supporting Blueberry Revision of XML

Working Draft for Supporting Blueberry Revision of XML Recommendation (1.0) with Particular Emphasis on Ethiopic Script and Writing System November 2001 This Version: http://www.digitaladdis.com/sk/ Ethiopics XML_Proposal_Version1.pdf Latest Ver.: http://www.digitaladdis.com/sk/ Ethiopics XML_Proposal_Version1.pdf Authors/Editors: Samuel Kinde Kassegne (Nanogen, UC San Diego, Engg Ext.) <[email protected]> Bibi Ephraim (Hewlett Packard) <[email protected]> Copyright ©2001, SKK, BE. Working Draft for Supporting Blueberry Revision of XML - Ethiopics Script 1 Abstract This document contains XML example codes, surveys and recommendations that support the need for Ethiopic script-based XML element type and attribute names in Amharic, Afaan Oromo, Tigrigna, Agewgna, Guragina, Hadiya, Harari, Sidama, Kembatigna and other Ethiopian languages that use Ethiopic script. Status of this Document This document is an initial working draft that is to be widely circulated for comment from the Ethiopic XML Interest Group and the wider public. The document is a work in progress. Table of Contents 1. Scope 2. Introduction 3. Objective 4. Review of Status of Native HTML and XML Applications in Ethiopic 4.1. Evolution of Ethiopic Content in HTML 4.2. Ethiopic and XML 5. Hybrid XML Document Markups in Ethiopic 5.1. Examples 5.2. Discussions 6. Fully-Native XML Document Markups in Ethiopic 6.1. Examples 6.2. Discussions 7. Conclusions and Recommendations 8. Appendix 9. References Working Draft for Supporting Blueberry Revision of XML - Ethiopics Script 2 1. Scope The work reported in this document contains XML example codes, surveys and recommendations that support the need for a revision of current XML standards to allow Ethiopic-based XML element type and attribute names in Amharic, Afaan Oromo, Tigrigna, Agewgna, Guragina, Hadiya, Harari, Sidama, Kembatigna and other Ethiopian languages that use Ethiopic script. -

Pronunciation

PRONUNCIATION Guide to the Romanized version of quotations from the Guru Granth Saheb. A. Consonants Gurmukhi letter Roman Word in Roman Word in Gurmukhi Meaning Letter letters using the letters using the relevant letter relevant letter from from the second the first column column S s Sabh sB All H h Het ihq Affection K k Krodh kroD Anger K kh Khayl Kyl Play G g Guru gurU Teacher G gh Ghar Gr House | ng Ngyani / gyani i|AwnI / igAwnI Possessing divine knowledge C c Cor cor Thief C ch Chaata Cwqw Umbrella j j Jahaaj jhwj Ship J jh Jhaaroo JwVU Broom \ ny Sunyi su\I Quiet t t Tap t`p Jump T th Thag Tg Robber f d Dar fr Fear F dh Dholak Folk Drum x n Hun hux Now q t Tan qn Body Q th Thuk Quk Sputum d d Den idn Day D dh Dhan Dn Wealth n n Net inq Everyday p p Peta ipqw Father P f Fal Pl Fruit b b Ben ibn Without B bh Bhagat Bgq Saint m m Man mn Mind X y Yam Xm Messenger of death r r Roti rotI Bread l l Loha lohw Iron v v Vasai vsY Dwell V r Koora kUVw Rubbish (n) in brackets, and (g) in brackets after the consonant 'n' both indicate a nasalised sound - Eg. 'Tu(n)' meaning 'you'; 'saibhan(g)' meaning 'by himself'. All consonants in Punjabi / Gurmukhi are sounded - Eg. 'pai-r' meaning 'foot' where the final 'r' is sounded. 3 Copyright Material: Gurmukh Singh of Raub, Pahang, Malaysia B. -

Maldives 2018.Pdf 3 Ibid

Diaspora engagement mapping MALDIVES Facts & figures Emigration Top countries of destination % of emigrants in % of which Sri Lanka 1,409 total population in the EU Australia 645 United Kingdom 402 India 194 South Africa 95 0.6% 16.5% 3,053 503 Political rights Dual citizenship1 53.5% 43.5% 46.5% 53.6% Right to vote in national elections for citizens residing abroad2 3 Remittances as a share of GDP: 0.1% Voting from abroad : Remittances inflow (USD billion): 4 At embassies/consulates REPUBLIC OF THE MALDIVES Terminology: In the 2014 census, the government referred to their diaspora as ‘non-resident’ Maldivians. The Maldives does not have a diaspora engagement policy.4 1 Maldivian Citizenship Act Law No. 1/95, https://www.refworld.org/pdfid/58d3c59b4.pdf 2 https://www.ifes.org/sites/default/files/ifes_maldives_parliamentary_elections_faqs_april_2019.pdf 3 Ibid. 4 https://publications.iom.int/system/files/pdf/mp_maldives_2018.pdf Overview of the policy and legislative framework 2006 Seventh National Development Plan included a policy on boosting the training of the labour force 2010 • through education and training for sectoral development. The first strategy under this policy was to maximise the utilisation of overseas fellowships for education and training. The Ministry of Higher Education has since listed a range of scholarships and loans on their website to encourage students to go abroad for either undergraduate or postgraduate studies, and 85 of these have been taken up. This shows the government encouraging its students to study abroad.5 Trends Given the relatively low number of Maldivians living abroad, engaging them is a challenge and therefore diaspora engagement has not been a priority for the Maldivian government. -

Maldives, Concealing an Enormity: the Media Blackout on the Destruction at the National Museum by Xavier Romero-Frias

Maldives, Concealing an Enormity: The media blackout on the destruction at the National Museum By Xavier Romero-Frias News items or papers documenting the planned and methodical destruction of the archaeological remains of Maldivian ancient history in 2012 are very rare. The irreplaceable antique coral stone pieces, remnants of the Buddhist period were kept at the National Museum of the Maldives in Male’, the capital. The collection, gathered from archaeological sites in different islands since HCP Bell’s excavations in the early 20th century, and carefully preserved, was systematically vandalized on 9 February 2012. The pieces of the Maldivian Buddhist past were displayed in the showcases of one of the new halls of the Museum that had been built by the government of China. Previously these invaluable artifacts had been kept on the floor in a room at the ground level. A leaflet had previously been issued by the Islamic Foundation of Maldives, a parastatal organization that had a pivotal role in the affair.1 Prior to the systematic vandalizing of the valuable museum pieces, the foundation distributed pamphlets calling for the destruction of the Maldivian archaeological patrimony. In defiance of all International laws and conventions, this shadowy, but influential body issued recommendations to the government that amounted to commands. In its pamphlets the Islamic Foundation of Maldives barefacedly demanded the immediate and thorough annihilation of the Maldivian archaeological heritage, including ancient Buddhist sculptures, temple and stupa structures, as well as their foundations, throughout the archipelago. Its unconcealed aim was the obliteration of all remains witnessing to ancient Maldivian Buddhist history, and even some remains of more recent times, such as the shrines of Muslim saints. -

Inventory of Romanization Tools

Inventory of Romanization Tools Standards Intellectual Management Office Library and Archives Canad Ottawa 2006 Inventory of Romanization Tools page 1 Language Script Romanization system for an English Romanization system for a French Alternate Romanization system catalogue catalogue Amharic Ethiopic ALA-LC 1997 BGN/PCGN 1967 UNGEGN 1967 (I/17). http://www.eki.ee/wgrs/rom1_am.pdf Arabic Arabic ALA-LC 1997 ISO 233:1984.Transliteration of Arabic BGN/PCGN 1956 characters into Latin characters NLC COPIES: BS 4280:1968. Transliteration of Arabic characters NL Stacks - TA368 I58 fol. no. 00233 1984 E DMG 1936 NL Stacks - TA368 I58 fol. no. DIN-31635, 1982 00233 1984 E - Copy 2 I.G.N. System 1973 (also called Variant B of the Amended Beirut System) ISO 233-2:1993. Transliteration of Arabic characters into Latin characters -- Part 2: Lebanon national system 1963 Arabic language -- Simplified transliteration Morocco national system 1932 Royal Jordanian Geographic Centre (RJGC) System Survey of Egypt System (SES) UNGEGN 1972 (II/8). http://www.eki.ee/wgrs/rom1_ar.pdf Update, April 2004: http://www.eki.ee/wgrs/ung22str.pdf Armenian Armenian ALA-LC 1997 ISO 9985:1996. Transliteration of BGN/PCGN 1981 Armenian characters into Latin characters Hübschmann-Meillet. Assamese Bengali ALA-LC 1997 ISO 15919:2001. Transliteration of Hunterian System Devanagari and related Indic scripts into Latin characters UNGEGN 1977 (III/12). http://www.eki.ee/wgrs/rom1_as.pdf 14/08/2006 Inventory of Romanization Tools page 2 Language Script Romanization system for an English Romanization system for a French Alternate Romanization system catalogue catalogue Azerbaijani Arabic, Cyrillic ALA-LC 1997 ISO 233:1984.Transliteration of Arabic characters into Latin characters. -

Map by Steve Huffman; Data from World Language Mapping System

Svalbard Greenland Jan Mayen Norwegian Norwegian Icelandic Iceland Finland Norway Swedish Sweden Swedish Faroese FaroeseFaroese Faroese Faroese Norwegian Russia Swedish Swedish Swedish Estonia Scottish Gaelic Russian Scottish Gaelic Scottish Gaelic Latvia Latvian Scots Denmark Scottish Gaelic Danish Scottish Gaelic Scottish Gaelic Danish Danish Lithuania Lithuanian Standard German Swedish Irish Gaelic Northern Frisian English Danish Isle of Man Northern FrisianNorthern Frisian Irish Gaelic English United Kingdom Kashubian Irish Gaelic English Belarusan Irish Gaelic Belarus Welsh English Western FrisianGronings Ireland DrentsEastern Frisian Dutch Sallands Irish Gaelic VeluwsTwents Poland Polish Irish Gaelic Welsh Achterhoeks Irish Gaelic Zeeuws Dutch Upper Sorbian Russian Zeeuws Netherlands Vlaams Upper Sorbian Vlaams Dutch Germany Standard German Vlaams Limburgish Limburgish PicardBelgium Standard German Standard German WalloonFrench Standard German Picard Picard Polish FrenchLuxembourgeois Russian French Czech Republic Czech Ukrainian Polish French Luxembourgeois Polish Polish Luxembourgeois Polish Ukrainian French Rusyn Ukraine Swiss German Czech Slovakia Slovak Ukrainian Slovak Rusyn Breton Croatian Romanian Carpathian Romani Kazakhstan Balkan Romani Ukrainian Croatian Moldova Standard German Hungary Switzerland Standard German Romanian Austria Greek Swiss GermanWalser CroatianStandard German Mongolia RomanschWalser Standard German Bulgarian Russian France French Slovene Bulgarian Russian French LombardRomansch Ladin Slovene Standard -

History of Giraavrau Island

History of Giraavrau Island According to tradition and the claims of the Giraavaru people, they were the ancient owners and rulers of the Maldives. Then a visiting foreign prince (Koimala Kalo) and his entourage asked for and were given their permission to settle on the neighboring island of Male''. Giraavaru island was much bigger, housing magnificent buildings and temples in those days, as the surrounding lagoon still testifies. Changing weather patterns gradually eroded the bulk of the island, which was once the capital of a proud and civilized people. Giraavaru island is on the western side of the lagoon of North Male' Atoll. It is not clear whether or not Giraavaru was its original name. Giraa means 'eroding' in the Maldivian language. It was thought that the island was called Giraavaru because it was gradually being eroded away into the sea. It is quite possible that the name proceeded the word. Indeed the word 'giraa' may have been coined as a result of the natural calamity that was claiming an important island. Giraavaru woman Overtaken by Immigrants The descendants of the foreign settlers soon took advantage of the environmental plight of the Giraavaru people and subjected them to their rule. Until the twentieth century, the Giraavaru people displayed recognisable physical, linguistic and cultural differences to the rest of the Maldive islanders. Social Differences The most celebrated difference was that while the rest of the Maldive islanders were polygamous according to Islamic custom, and boasted the highest divorce rate in the world, the Giraavaru people were strictly monogamous and did not permit divorce.