Challenging Boundaries: the History and Reception of American Studio Glass 1960 to 1990

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

20Th Century Art & Design Auction September 9 • Sale Results

20th Century Art & Design Auction September 9 • Sale Results * The prices listed do not include the buyers premium. Results are subject to change. unsold $ Lot # Title high bid 088 Rookwood vase, incised and painted stylized floral 950 Darling 275 00 Gustav Stickley Morris chair, #336 0000 09 Hampshire bowl, organic green matt glaze 200 70 Frank J. Marshall box 200 002 Gustave Baumann woodblock, 5000 092 Pewabic vase, shouldered hand-thrown shape 850 7 Indiana Engraving Company print 600 004 Arts & Crafts tinder box, slanted lift top 650 093 Van Briggle vase, ca. 907-92, squat form 550 72 Hiroshige (Japanese 796-858), colorful woodblock print 005 Rookwood vase, geometric design 325 094 Hull House bowl, low form 200 600 006 Arts & Crafts graphic, 350 095 Rookwood vase, three-handled form 300 73 Arts & Crafts wall hanging, wood panel 400 007 Limbert bookcase, #358, two door form 2200 096 Gustav Stickley Chalet desk, #505 2200 74 Hiroshige (Japanese 796-858), colorful woodblockw/ 008 Gustav Stickley china cabinet 800 097 Gustav Stickley bookcase, #75 2600 Kunihisa Utagawa 450 009 Weller Coppertone vase, flaring form 250 098 Gustav Stickley china cabinet, #85 5500 75 Gustav Stickley desk, #720, two drawers 800 00 Armen Haireian vase, 275 00 Shreve blotter ends, attribution, hammered copper 400 76 Rookwood vase, bulbous shape covered in a green matt 011 Grueby vase, rare light blue suspended matt glaze 400 0 Arts & Crafts table runner, embroidered poppy designs 350 glaze 1100 02 Van Briggle tile, incised and painted landscape 200 02 Arts & Crafts blanket chest 950 77 Gustav Stickley sideboard, #89, three drawers 5000 03 Fulper vase, large tapering form 425 04 Heintz desk set, 325 78 Arts & Crafts tabouret, hexagonal top 400 04 Van Briggle tile, incised and painted landscape 2300 05 Navajo rug, stylized diamond design 450 79 Gustav Stickley Thornden side chair, #299 75 05 Newcomb College handled vessel, bulbous shape 300 06 L & JG Stickley dining chairs, #800, set of six 2000 80 Arts & Crafts tabouret, octagonal top 375 06 Van Briggle vase, ca. -

Graphic Recording by Terry Laban of the Global Health Matters Forum on March 25, 2020 Co-Hosted by Craftnow and the Foundation F

Graphic Recording by Terry LaBan of the Global Health Matters Forum on March 25, 2020 Co-Hosted by CraftNOW and the Foundation for Advancement of International Medical Education and Research With Gratitude to Our 2020 Contributors* $10,000 + Up to $500 Jane Davis Barbara Adams Drexel University Lenfest Center for Cultural Anonymous Partnerships Jeffrey Berger Patricia and Gordon Fowler Sally Bleznack Philadelphia Cultural Fund Barbara Boroff Poor Richard’s Charitable Trust William Burdick Lisa Roberts and David Seltzer Erik Calvo Fielding Rose Cheney and Howie Wiener $5,000 - $9,999 Rachel Davey Richard Goldberg Clara and Ben Hollander Barbara Harberger Nancy Hays $2,500 - $4,999 Thora Jacobson Brucie and Ed Baumstein Sarah Kaizar Joseph Robert Foundation Beth and Bill Landman Techné of the Philadelphia Museum of Art Tina and Albert Lecoff Ami Lonner $1,000 - $2,499 Brenton McCloskey Josephine Burri Frances Metzman The Center for Art in Wood Jennifer-Navva Milliken and Ron Gardi City of Philadelphia Office of Arts, Culture, and Angela Nadeau the Creative Economy, Greater Philadelphia Karen Peckham Cultural Alliance and Philadelphia Cultural Fund Pentimenti Gallery The Clay Studio Jane Pepper Christina and Craig Copeland Caroline Wishmann and David Rasner James Renwick Alliance Natalia Reyes Jacqueline Lewis Carol Saline and Paul Rathblatt Suzanne Perrault and David Rago Judith Schaechter Rago Auction Ruth and Rick Snyderman Nicholas Selch Carol Klein and Larry Spitz James Terrani Paul Stark Elissa Topol and Lee Osterman Jeffrey Sugerman -

The Factory of Visual

ì I PICTURE THE MOST COMPREHENSIVE LINE OF PRODUCTS AND SERVICES "bey FOR THE JEWELRY CRAFTS Carrying IN THE UNITED STATES A Torch For You AND YOU HAVE A GOOD PICTURE OF It's the "Little Torch", featuring the new controllable, méf » SINCE 1923 needle point flame. The Little Torch is a preci- sion engineered, highly versatile instrument capa- devest inc. * ble of doing seemingly impossible tasks with ease. This accurate performer welds an unlimited range of materials (from less than .001" copper to 16 gauge steel, to plastics and ceramics and glass) with incomparable precision. It solders (hard or soft) with amazing versatility, maneuvering easily in the tightest places. The Little Torch brazes even the tiniest components with unsurpassed accuracy, making it ideal for pre- cision bonding of high temp, alloys. It heats any mate- rial to extraordinary temperatures (up to 6300° F.*) and offers an unlimited array of flame settings and sizes. And the Little Torch is safe to use. It's the big answer to any small job. As specialists in the soldering field, Abbey Materials also carries a full line of the most popular hard and soft solders and fluxes. Available to the consumer at manufacturers' low prices. Like we said, Abbey's carrying a torch for you. Little Torch in HANDY KIT - —STARTER SET—$59.95 7 « '.JBv STARTER SET WITH Swest, Inc. (Formerly Southwest Smelting & Refining REGULATORS—$149.95 " | jfc, Co., Inc.) is a major supplier to the jewelry and jewelry PRECISION REGULATORS: crafts fields of tools, supplies and equipment for casting, OXYGEN — $49.50 ^J¡¡r »Br GAS — $49.50 electroplating, soldering, grinding, polishing, cleaning, Complete melting and engraving. -

Glass Pavilion Floorplan

MyGuide A Monroe Street Lobbey Dale Chihuly, Chandelier: Campiello del Remer #2, 1996/2006 Dale Chihuly’s “chandelier” greets visitors at the Monroe Street entrance. Chihuly’s team installed the 1300-pound hanging sculpture so that its 243 components complement the arcs of the curved walls and the Crystal Corridor that bisects the Glass Pavilion floorplan. B Gallery 5 Roman, Jar with Basket Handle, late 4th–5th century Glass The most elaborate jar of its type known from the late Eastern Roman world, this is one of thousands “As physical borders blur and of glass objects given by glass industrialist and TMA founder/benefactor Edward Drummond Libbey blend, so do notions such as Pavilion (1854–1925) of the Libbey Glass Company. He wanted the Museum to display a comprehensive program and context. This fits Since opening in August 2006, the history of glass art for the education and enjoyment the dynamic environment at the Toledo Museum of Art Glass Pavilion of the community. The Museum continues to build on has attracted a lot of attention from his vision today. Toledo Museum of Art, where around the world. This guide sheds a a wide range of collections little light on this architectural marvel are allowed to interact in new and the stellar collection it houses. C The Glass Study Gallery The Glass Study Gallery provides open storage of constellations, where workshop works not on display in the exhibition galleries. interacts with collection…and Divided into cases featuring ancient, European, American, and contemporary glass, the Study Gallery where the Museum campus allows visitors to compare many examples of similar objects, to contrast different techniques, and to enjoy interacts with neighborhood and the full range of the Museum’s varied collection. -

Newsletter Fall 2011 DATED Decorative Arts Society Arts Decorative Secretary C/O Lindsy R

newsletter fall 2011 Volume 19, Number 2 Decorative Arts Society DAS Newsletter Volume 19 Editor Gerald W.R. Ward Number 2 Katharine Lane Weems Senior Curator Fall 2011 of American Decorative Arts and Sculpture The DAS Museum of Fine Arts, Boston The DAS Newsletter is a publication of Boston, MA the Decorative Arts Society, Inc. The pur- pose of the DAS Newsletter is to serve as a The Decorative Arts Society, Inc., is a not- forum for communication about research, Coordinator exhibitions, publications, conferences and Ruth E. Thaler-Carter in 1990 for the encouragement of interest other activities pertinent to the serious Freelance Writer/Editor in,for-profit the appreciation New York of,corporation and the exchange founded of study of international and American deco- Rochester, NY information about the decorative arts. To rative arts. Listings are selected from press pursue its purposes, the Society sponsors releases and notices posted or received Advisory Board meetings, programs, seminars, and a news- from institutions, and from notices submit- Michael Conforti letter on the decorative arts. Its supporters ted by individuals. We reserve the right to Director include museum curators, academics, col- reject material and to edit materials for Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute lectors and dealers. length or clarity. Williamstown, MA The DAS Newsletter welcomes submis- Officers sions, preferably in digital format, submit- Wendy Kaplan President ted by e-mail in Plain Text or as Word Department Head and Curator, David L. Barquist attachments, or on a CD and accompanied Decorative Arts H. Richard Dietrich, Jr., Curator by a paper copy. -

Download New Glass Review 15

eview 15 The Corning Museum of Glass NewGlass Review 15 The Corning Museum of Glass Corning, New York 1994 Objects reproduced in this annual review Objekte, die in dieser jahrlich erscheinenden were chosen with the understanding Zeitschrift veroffentlicht werden, wurden unter that they were designed and made within der Voraussetzung ausgewahlt, daB sie inner- the 1993 calendar year. halb des Kalenderjahres 1993 entworfen und gefertigt wurden. For additional copies of New Glass Review, Zusatzliche Exemplare der New Glass Review please contact: konnen angefordert werden bei: The Corning Museum of Glass Sales Department One Museum Way Corning, New York 14830-2253 Telephone: (607) 937-5371 Fax: (607) 937-3352 All rights reserved, 1994 Alle Rechte vorbehalten, 1994 The Corning Museum of Glass The Corning Museum of Glass Corning, New York 14830-2253 Corning, New York 14830-2253 Printed in Frechen, Germany Gedruckt in Frechen, Bundesrepublik Deutschland Standard Book Number 0-87290-133-5 ISSN: 0275-469X Library of Congress Catalog Card Number Aufgefuhrt im Katalog der Library of Congress 81-641214 unter der Nummer 81 -641214 Table of Contents/lnhalt Page/Seite Jury Statements/Statements der Jury 4 Artists and Objects/Kunstlerlnnen und Objekte 10 Bibliography/Bibliographie 30 A Selective Index of Proper Names and Places/ Ausgewahltes Register von Eigennamen und Orten 58 etztes Jahr an dieser Stelle beklagte ich, daB sehr viele Glaskunst- Jury Statements Ller aufgehort haben, uns Dias zu schicken - odervon vorneherein nie Zeit gefunden haben, welche zu schicken. Ich erklarte, daB auch wenn die Juroren ein bestimmtes Dia nicht fur die Veroffentlichung auswahlen, alle Dias sorgfaltig katalogisiert werden und ihnen ein fester Platz in der Forschungsbibliothek des Museums zugewiesen ast year in this space, I complained that a large number of glass wird. -

Press Release for Editing

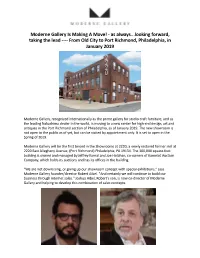

Moderne Gallery Is Making A Move! - as always...looking forward, taking the lead ---- From Old City to Port Richmond, Philadelphia, in January 2019 Moderne Gallery, recognized internationally as the prime gallery for studio craft furniture, and as the leading Nakashima dealer in the world, is moving to a new center for high end design, art and antiques in the Port Richmond section of Philadelphia, as of January 2019. The new showroom is not open to the public as of yet, but can be visited by appointment only. It is set to open in the Spring of 2019. Moderne Gallery will be the first tenant in the Showrooms at 2220, a newly restored former mill at 2220 East Allegheny Avenue, (Port Richmond) Philadelphia, PA 19134. The 100,000 square-foot building is owned and managed by Jeffrey Kamal and Joe Holahan, co-owners of Kamelot Auction Company, which holds its auctions and has its offices in the building. "We are not downsizing, or giving up our showroom concept with special exhibitions," says Moderne Gallery founder/director Robert Aibel. "And certainly we will continue to build our business through internet sales." Joshua Aibel, Robert's son, is now co-director of Moderne Gallery and helping to develop this combination of sales concepts. "We see this as an opportunity to move to a setting that presents a comprehensive, easily accessible major art, antiques and design center for our region, just off I-95," says Josh Aibel. "The Showrooms at 2220 offer an attractive new venue with great showroom spaces and many advantages for our storage and shipping requirements." Moderne Gallery's new showrooms are being designed by the gallery's longtime interior designer Michael Gruber of Philadelphia. -

![Ceramics Monthly / \ Pottery \ MAKER MONTHLY ~ ] Power Driven \~ Variable Speed Volume 19, Number 3 March 1971 $595O Letters to the Editor](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1414/ceramics-monthly-pottery-maker-monthly-power-driven-variable-speed-volume-19-number-3-march-1971-595o-letters-to-the-editor-821414.webp)

Ceramics Monthly / \ Pottery \ MAKER MONTHLY ~ ] Power Driven \~ Variable Speed Volume 19, Number 3 March 1971 $595O Letters to the Editor

f i! li I /i /! .>, / /I I /i i II ...j • I ~i ~ ~ L =~ ,~ ~ ~ ~i!~=i~ ~V~ ~ i~~ ~ i~i ¸¸¸¸¸'I~!i!ii ¸ • ~i ~ ~L ~ ~,~:~i!ii~iL~!~i~ii~!::~~ ~ :~ !~!~ ~L~I~I ~ ~ ~!i~ ::i, i~::~i:~ i:~i~iiiiii~i!~ ;~i~i,~i~i~i~i~ii~i~m~ For Hobbyists • Schools • Art & Craft Centers * Institutions Manufactured by GILMOUR CAMPBELL 14258 Maiden - Detroit, Michigan 48213 KINGSPIN Electric Banding Wheel KINGSPIN Wheel • Heavy Kinalloy 7-inch table NEW with Wagon Wheel Base • Top and base are cast Kinalloy • New m with height trimmer • Top measures 61/4', • Shipping weight 3 Ibs. • Solid cast aluminum case • 110 volt motor, 35 RPM Model W-6 only .......... $4.25 • On & Off switch, g-ft. cord • One-year service guarantee With 7 inch table • For light throwing Model W-7 ................. $5.25 Model E-2 .............. $21.95 With 8 inch table E-2T with trimmer ........... $23.95 Model W-8 ................. $7.25 Model E-3T................ $27.50 (More power for light throwing) With 10 inch table E-3 less trimmer ........... $25.50 Model W-10 ................ $9.50 KINGSPIN Kinolite Turntable KINGSPIN Kinalloy Turntable New 12-1nch model with many uses • A 12-inch wheel for the price • 10" model of an g-inch • Made of KINOLITE m latest slnktop material used • Heavy KINALLOY Table in newest homes • Heavy Kinalloy round base • Just the thing to use on those lace dolls. • Heavy Kinalloy round base • Easy Spinning With Wagon Wheel Base Model W-12 ................ $6.25 Model KR-7 .............. $6.25 With 7" Table With 12-inch Aluminum Table ~ Model KR-8 ................ -

Antonio Prieto; » Julio Aè Pared 30 a Craftsman5 Ipko^Otonmh^

Until you see and feel Troy Weaving Yarns . you'll find it hard to believe you can buy such quality, beauty and variety at such low prices. So please send for your sample collection today. and Textile Company $ 1.00 brings you a generous selection of the latest and loveliest Troy quality controlled yarns. You'll find new 603 Mineral Spring Avenue, Pawtucket, R. I. 02860 pleasure and achieve more beautiful results when you weave with Troy yarns. »««Él Mm m^mmrn IS Dialogue .n a « 23 Antonio Prieto; » Julio Aè Pared 30 A Craftsman5 ipKO^OtONMH^ IS«« MI 5-up^jf à^stoneware "iactogram" vv.i is a pòìnt of discussion in Fred-Schwartz's &. Countercues A SHOPPING CENTER FOR JEWELRY CRAFTSMEN at your fingertips! complete catalog of... TOOLS AND SUPPLIES We've spent one year working, compiling and publishing our new 244-page Catalog 1065 ... now it is available. In the fall of 1965, the Poor People's Corporation, a project of the We're mighty proud of this new one... because we've incor- SNCC (Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee), sought skilled porated brand new never-before sections on casting equipment, volunteer craftsmen for training programs in the South. At that electroplating equipment and precious metals... time, the idea behind the program was to train local people so that they could organize cooperative workshops or industries that We spent literally months redesigning the metals section . would help give them economic self-sufficiency. giving it clarity ... yet making it concise and with lots of Today, PPC provides financial and technical assistance to fifteen information.. -

Download New Glass Review 11

The Corning Museum of Glass NewGlass Review 11 The Corning Museum of Glass Corning, New York 1990 Objects reproduced in this annual review Objekte, die in dieser jahrlich erscheinenden were chosen with the understanding Zeitschrift veroffentlicht werden, wurden unter that they were designed and made within derVoraussetzung ausgewahlt, da(3 sie the 1989 calendar year. innerhalb des Kalenderjahres 1989 entworfen und gefertigt wurden. For additional copies of New Glass Review, Zusatzliche Exemplare des New Glass Review please contact: konnen angefordert werden bei: The Corning Museum of Glass Sales Department One Museum Way Corning, New York 14830-2253 (607) 937-5371 All rights reserved, 1990 Alle Rechte vorbehalten, 1990 The Corning Museum of Glass The Corning Museum of Glass Corning, New York 14830-2253 Corning, New York 14830-2253 Printed in Dusseldorf FRG Gedruckt in Dusseldorf, Bundesrepublik Deutschland Standard Book Number 0-87290-122-X ISSN: 0275-469X Library of Congress Catalog Number Aufgefuhrt im Katalog der KongreB-Bucherei 81-641214 unter der Nummer 81-641214 Table of Contents/lnhalt Page/Seite Jury Statements/Statements der Jury 4 Artists and Objects/Kunstler und Objekte 9 Bibliography/Bibliographie 30 A Selective Index of Proper Names and Places/ Verzeichnis der Eigennamen und Orte 53 Is das Jury-Mitglied, das seit dem Beginn der New Glass Review Jury Statements A1976 kein Jahr verpaBt hat, fuhle ich mich immer dazu verpflichtet, neueTrends und Richtungen zu suchen und daruber zu berichten, wel- chen Weg Glas meiner Meinung nach einschlagt. Es scheint mir zum Beispiele, daB es immer mehr Frauen in der Review gibt und daB ihre Arbeiten zu den Besten gehoren. -

Over-The-Summer Issue JUNE, 1963 50C It's in the National

Over-the-Summer Issue JUNE, 1963 50c It's in the national g spotlight! The New CM Handbook on Ceramic Pro _< 64 Pages of Instruction * Over 200 Illustrations * 3-Color Cover * 81kxll Format From the wealth of material presented in CERAMICS Here's A Partial List of the Projects Included MONTHLY during the past decade, the editors have se- CLAY TOYS THAT MOVE ...... by Earl Hassenpflug lected an outstanding collection of articles by recognized COIL BUILDING VASE .......... by Richard Peeler authorities in the ceramic world. Each of these articles CLAY WHISTLES .................. by Helen Young has been carefully edited for presentation in book form HAND-FORMING USING A PADDLE ___ by Don Wood and is complete with large, clear photographs and step- LEAF-PRESSED POTTERY ........ by-step text. by Edris Eckhardt BUILT-IN SLAB HANDLES ........ by Irene Priced at only two dollars per copy, this stimulating Kettner compilation will find wide circulation among hobbyists, CERAMIC SCREENS ............ by F. Carlton Ball craft groups and schools. BOTTLE INTO A TEAPOT ....... by Tom Spencer AN INDOOR FOUNTAIN ............ by John Kenny z ~ HANGING PLANTERS .............. by Alice Lasher SAND BAG MOLDS .............. by Louise Griffiths CERAMICS MONTHLY BOOK DEPT. -mEt USE A STONE FOUNDATION .... by Lucia B. Comins 4175 N. HIGH ST., COLUMBUS, OHIO SEVEN DECORATING TECHNIQUES ___by Karl Martz DECORATION ON GLYCERIN ....... by Marc Bellaire Please send me ...... copies of the CERAMIC PROJECTS BALLOONS AS MOLDS --- by Reinhold P. Marxhausen Handbook @ $2 per copy. (CM pays postage.) CARVED GREENWARE MASKS .... by Phyllis Cusick ROLLING PIN "- ~ME SCULPTURE .......... by John Kenny KACHINA DOLL JEW-ELRY ......... by Peg Townsend ADDR~q~ CHILDREN OBSERVED ............. -

Research Resources at the Smithsonian American Art Museum Amelia A

From La Farge to Paik Research Resources at the Smithsonian American Art Museum Amelia A. Goerlitz A wealth of materials related to artistic interchange between the United States and Asia await scholarly attention at the Smithsonian Institution.1 The Smithsonian American Art Museum in particular owns a remarkable number of artworks that speak to the continuous exchange between East and West. Many of these demonstrate U.S. fascination with Asia and its cultures: prints and paintings of America’s Chinatowns; late-nineteenth- century examples of Orientalism and Japonisme; Asian decorative arts and artifacts donated by an American collector; works by Anglo artists who trav- eled to Asia and India to depict their landscapes and peoples or to study traditional printmaking techniques; and post-war paintings that engage with Asian spirituality and calligraphic traditions. The museum also owns hundreds of works by artists of Asian descent, some well known, but many whose careers are just now being rediscovered. This essay offers a selected overview of related objects in the collection. West Looks East American artists have long looked eastward—not only to Europe but also to Asia and India—for subject matter and aesthetic inspiration. They did not al- ways have to look far. In fact, the earliest of such works in the American Art Mu- seum’s collection consider with curiosity, and sometimes animosity, the presence of Asians in the United States. An example is Winslow Homer’s engraving enti- tled The Chinese in New York—Scene in a Baxter Street Club-House, which was produced for Harper’s Weekly in 1874.