Violence and Belonging

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dasu Hydropower Project

Public Disclosure Authorized PAKISTAN WATER AND POWER DEVELOPMENT AUTHORITY (WAPDA) Public Disclosure Authorized Dasu Hydropower Project ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL ASSESSMENT Public Disclosure Authorized EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Report by Independent Environment and Social Consultants Public Disclosure Authorized April 2014 Contents List of Acronyms .................................................................................................................iv 1. Introduction ...................................................................................................................1 1.1. Background ............................................................................................................. 1 1.2. The Proposed Project ............................................................................................... 1 1.3. The Environmental and Social Assessment ............................................................... 3 1.4. Composition of Study Team..................................................................................... 3 2. Policy, Legal and Administrative Framework ...............................................................4 2.1. Applicable Legislation and Policies in Pakistan ........................................................ 4 2.2. Environmental Procedures ....................................................................................... 5 2.3. World Bank Safeguard Policies................................................................................ 6 2.4. Compliance Status with -

Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Current Rain Spell (31082020 to 04092020 at 11:00 Pm)

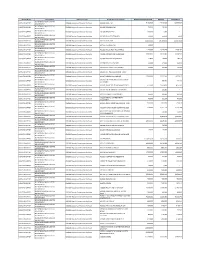

PDMA PROVINCIAL DISASTER MANAGEMENT AUTHORITY Provincial Emergency Operation Center Civil Secretariat, Peshawar, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Phone: (091) 9212059, 9213845, Fax: (091) 9214025 www.pdma.gov.pk No. PDMA/PEOC/SR/2020/SepM125 Date: 04/09/2020 KHYBER PAKHTUNKHWA CURRENT RAIN SPELL (31082020 TO 04092020 AT 11:00 PM) INFRA/ HUMAN INCIDENTS NATURE OF CAUSE OF CATTLE DISTRICT HUMAN LOSSES/ INJURIES INFRASTRUCTURE DAMAGES INCIDENT INCIDENT PERISHED DEATH INJURED HOUSES SCHOOLS OTHERS Male Female Child Total Male Female Child Total Fully Partially Total Fully Partially Total Fully Partially Total House Collapse/Room Mardan Heavy Rain 0 0 0 0 4 4 1 9 0 0 6 6 0 0 0 0 0 0 Collapse Boundry Wall Collapse/Cattle Swabi Heavy Rain Shed/House 0 1 4 5 4 1 3 8 1 1 9 10 0 0 0 0 0 0 Collapse/Room Burnt/Room Collapse House Collapse/Room Charsadda Heavy Rain 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 0 0 2 2 0 0 0 0 0 0 Collapse Nowshera Heavy Rain House Collapse 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 11 11 0 0 0 0 0 0 Boundry Wall Collapse/Cattle Shed/House Buner Heavy Rain 0 2 3 5 0 1 2 3 5 6 121 127 0 0 0 0 0 0 Collapse/Roof Collapse/Room Collapse House Collapse/Room UpperChitral Heavy Rain 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 2 0 2 0 0 0 0 5 5 Collapse Malakand Heavy Rain House Collapse 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 14 14 0 0 0 0 0 0 Lower Dir Heavy Rain House Collapse 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 8 8 0 0 0 0 0 0 Boundry Wall Collapse/House Shangla Heavy Rain Collapse/Roof 1 0 3 4 0 4 2 6 12 2 40 42 0 0 0 0 2 2 Collapse/Room Collapse Boundry Wall Collapse/Flash Heavy Rain/Land Flood/Heavy Swat 7 2 2 11 5 0 4 9 0 3 27 30 0 0 -

Languages of Kohistan. Sociolinguistic Survey of Northern

SOCIOLINGUISTIC SURVEY OF NORTHERN PAKISTAN VOLUME 1 LANGUAGES OF KOHISTAN Sociolinguistic Survey of Northern Pakistan Volume 1 Languages of Kohistan Volume 2 Languages of Northern Areas Volume 3 Hindko and Gujari Volume 4 Pashto, Waneci, Ormuri Volume 5 Languages of Chitral Series Editor Clare F. O’Leary, Ph.D. Sociolinguistic Survey of Northern Pakistan Volume 1 Languages of Kohistan Calvin R. Rensch Sandra J. Decker Daniel G. Hallberg National Institute of Summer Institute Pakistani Studies of Quaid-i-Azam University Linguistics Copyright © 1992 NIPS and SIL Published by National Institute of Pakistan Studies, Quaid-i-Azam University, Islamabad, Pakistan and Summer Institute of Linguistics, West Eurasia Office Horsleys Green, High Wycombe, BUCKS HP14 3XL United Kingdom First published 1992 Reprinted 2002 ISBN 969-8023-11-9 Price, this volume: Rs.300/- Price, 5-volume set: Rs.1500/- To obtain copies of these volumes within Pakistan, contact: National Institute of Pakistan Studies Quaid-i-Azam University, Islamabad, Pakistan Phone: 92-51-2230791 Fax: 92-51-2230960 To obtain copies of these volumes outside of Pakistan, contact: International Academic Bookstore 7500 West Camp Wisdom Road Dallas, TX 75236, USA Phone: 1-972-708-7404 Fax: 1-972-708-7433 Internet: http://www.sil.org Email: [email protected] REFORMATTING FOR REPRINT BY R. CANDLIN. CONTENTS Preface............................................................................................................viii Maps................................................................................................................. -

Pakistan, Country Information

Pakistan, Country Information PAKISTAN ASSESSMENT April 2003 Country Information and Policy Unit I SCOPE OF DOCUMENT II GEOGRAPHY III ECONOMY IV HISTORY V STATE STRUCTURES VI HUMAN RIGHTS VIA. HUMAN RIGHTS ISSUES VIB. HUMAN RIGHTS - SPECIFIC GROUPS VIC. HUMAN RIGHTS - OTHER ISSUES ANNEX A: CHRONOLOGY OF MAJOR EVENTS ANNEX B: POLITICAL ORGANISATIONS AND OTHER GROUPS ANNEX C: PROMINENT PEOPLE ANNEX D: REFERENCES TO SOURCE MATERIAL 1. SCOPE OF DOCUMENT 1.1 This assessment has been produced by the Country Information and Policy Unit, Immigration and Nationality Directorate, Home Office, from information obtained from a wide variety of recognised sources. The document does not contain any Home Office opinion or policy. 1.2 The assessment has been prepared for background purposes for those involved in the asylum / human rights determination process. The information it contains is not exhaustive. It concentrates on the issues most commonly raised in asylum / human rights claims made in the United Kingdom. 1.3 The assessment is sourced throughout. It is intended to be used by caseworkers as a signpost to the source material, which has been made available to them. The vast majority of the source material is readily available in the public domain. These sources have been checked for currency, and as far as can be ascertained, remained relevant and up to date at the time the document was issued. 1.4 It is intended to revise the assessment on a six-monthly basis while the country remains within the top 35 asylum-seeker producing countries in the United Kingdom. 2. GEOGRAPHY file:///V|/vll/country/uk_cntry_assess/apr2003/0403_Pakistan.htm[10/21/2014 9:56:32 AM] Pakistan, Country Information General 2.1 The Islamic Republic of Pakistan lies in southern Asia, bordered by India to the east and Afghanistan and Iran to the west. -

Audit Report on the Accounts of Earthquake Reconstruction & Rehabilitation Authority Audit Year 2015-16

AUDIT REPORT ON THE ACCOUNTS OF EARTHQUAKE RECONSTRUCTION & REHABILITATION AUTHORITY AUDIT YEAR 2015-16 AUDITOR GENERAL OF PAKISTAN TABLE OF CONTENTS ABBREVIATIONS & ACRONYMS ........................................................................... i PREFACE .............................................................................................................. vi EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................................ vii SUMMARY TABLES & CHARTS ..............................................................................1 I Audit Work Statistics ..............................................................................1 II Audit observations regarding Financial Management ...........1 III Outcome Statistics ............................................................................2 IV Table of Irregularities pointed out ..............................................3 V Cost-Benefit ........................................................................................3 CHAPTER-1 Public Financial Management Issues (Earthquake Reconstruction & Rehabilitation Authority 1.1 Audit Paras .............................................................................................4 CHAPTER-2 Earthquake Reconstruction & Rehabilitation Authority (ERRA) 2.1 Introduction of Authority .....................................................................18 2.2 Comments on Budget & Accounts (Variance Analysis) .....................18 2.3 Brief comments on the status of compliance -

Contesting Candidates NA-1 Peshawar-I

Form-V: List of Contesting Candidates NA-1 Peshawar-I Serial No Name of contestng candidate in Address of contesting candidate Symbol Urdu Alphbeticl order Allotted 1 Sahibzada PO Ashrafia Colony, Mohala Afghan Cow Colony, Peshawar Akram Khan 2 H # 3/2, Mohala Raza Shah Shaheed Road, Lantern Bilour House, Peshawar Alhaj Ghulam Ahmad Bilour 3 Shangar PO Bara, Tehsil Bara, Khyber Agency, Kite Presented at Moh. Gul Abad, Bazid Khel, PO Bashir Ahmad Afridi Badh Ber, Distt Peshawar 4 Shaheen Muslim Town, Peshawar Suitcase Pir Abdur Rehman 5 Karim Pura, H # 282-B/20, St 2, Sheikhabad 2, Chiragh Peshawar (Lamp) Jan Alam Khan Paracha 6 H # 1960, Mohala Usman Street Warsak Road, Book Peshawar Haji Shah Nawaz 7 Fazal Haq Baba Yakatoot, PO Chowk Yadgar, H Ladder !"#$%&'() # 1413, Peshawar Hazrat Muhammad alias Babo Maavia 8 Outside Lahore Gate PO Karim Pura, Peshawar BUS *!+,.-/01!234 Khalid Tanveer Rohela Advocate 9 Inside Yakatoot, PO Chowk Yadgar, H # 1371, Key 5 67'8 Peshawar Syed Muhammad Sibtain Taj Agha 10 H # 070, Mohala Afghan Colony, Peshawar Scale 9 Shabir Ahmad Khan 11 Chamkani, Gulbahar Colony 2, Peshawar Umbrella :;< Tariq Saeed 12 Rehman Housing Society, Warsak Road, Fist 8= Kababiyan, Peshawar Amir Syed Monday, April 22, 2013 6:00:18 PM Contesting candidates Page 1 of 176 13 Outside Lahori Gate, Gulbahar Road, H # 245, Tap >?@A= Mohala Sheikh Abad 1, Peshawar Aamir Shehzad Hashmi 14 2 Zaman Park Zaman, Lahore Bat B Imran Khan 15 Shadman Colony # 3, Panal House, PO Warsad Tiger CDE' Road, Peshawar Muhammad Afzal Khan Panyala 16 House # 70/B, Street 2,Gulbahar#1,PO Arrow FGH!I' Gulbahar, Peshawar Muhammad Zulfiqar Afghani 17 Inside Asiya Gate, Moh. -

Their Uses and Degrees of Risk of Extinc

Saudi Journal of Biological Sciences 28 (2021) 3076–3093 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Saudi Journal of Biological Sciences journal homepage: www.sciencedirect.com Original article Medicinal plants resources of Western Himalayan Palas Valley, Indus Kohistan, Pakistan: Their uses and degrees of risk of extinction ⇑ Mohammad Islam a, , Inamullah a, Israr Ahmad b, Naveed Akhtar c, Jan Alam d, Abdul Razzaq c, Khushi Mohammad a, Tariq Mahmood e, Fahim Ullah Khan e, Wisal Muhammad Khan c, Ishtiaq Ahmad c, ⇑ Irfan Ullah a, Nosheen Shafaqat e, Samina Qamar f, a Department of Genetics, Hazara University, Mansehra 21300, KP, Pakistan b Department of Botany, Women University, AJK, Pakistan c Department of Botany, Islamia College University, 25120 KP, Peshawar, Pakistan d Department of Botany, Hazara University, Mansehra 21300, KP, Pakistan e Department of Agriculture, Hazara University, Mansehra, KP, Pakistan f Department of Zoology, Govt. College University, Faisalabad, Pakistan article info abstract Article history: Present study was intended with the aim to document the pre-existence traditional knowledge and eth- Received 29 December 2020 nomedicinal uses of plant species in the Palas valley. Data were collected during 2015–2016 to explore Revised 10 February 2021 plants resource, their utilization and documentation of the indigenous knowledge. The current study Accepted 14 February 2021 reported a total of 65 medicinal plant species of 57 genera belonging to 40 families. Among 65 species, Available online 22 February 2021 the leading parts were leaves (15) followed by fruits (12), stem (6) and berries (1), medicinally significant while, 13 plant species are medicinally important for rhizome, 4 for root, 4 for seed, 4 for bark and 1 each Keywords: for resin. -

Pak-Swiss INRMP (2010) Study on Timber Harvesting Ban in NWFP

2 Study on timber harvesting ban in NWFP, Pakistan Disclaimer This study was conducted in an independent manner. The views expressed in this study do not present the official position of the NWFP Forest Department and the funding agency (SDC) but those of the Study Team ISBN: 969-9082-02-x Parts of this publication may be copied with proper citation in favour of the Authors and the publishing organization Integrated Natural Resource Management Project 3 This publication is based on 15 months continuous engagement of the team in collecting data, analyses and documentation by the study team. Initiated by: Pak-Swiss Integrated Natural Resource Management Project (INRMP) on request of the NWFP Forest Department in the first yearly planning workshop of the project, to conduct an independent study The Study Team and Authors: Dr. Knut M. Fischer (Team Leader) Muhammad Hanif Khan Alamgir Khan Gandapur Abdul Latif Rao Raja Muhammad Zarif Hamid Marwat Publication editing: Arjumand Nizami Syed Nadeem Bukhari Fatima Daud Kamal Layout: Salman Beenish Printing: PanGraphics (Pvt) Ltd., Islamabad Available from: Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC) Intercooperation Delegation Office Pakistan INRMP / NWFP Forest Department, Planning, Monitoring and Evaluation Circle, Peshawar Cover photographs: Aamir Rana Amina Ijaz Arjumand Nizami Irshad Ali Mian Roshan Ara Tahir Saleem Technical cooperation: Intercooperation Head Office Berne, Switzerland and Pakistan Pak-Swiss Integrated Natural Resource Management Project (INRMP) GIS lab of Forest Planning and Monitoring Circle, NWFP Forest Department Published by Intercooperation Pakistan through Pak-Swiss Integrated Natural Resource Management Project (INRMP). INRMP is funded by Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC) 4 Study on timber harvesting ban in NWFP, Pakistan About Intercooperation Intercooperation (IC) in Pakistan and worldwide has been actively engaged in forestry sector right from its inception in 1982. -

1951-81 Population Administrative . Units

1951- 81 POPULATION OF ADMINISTRATIVE . UNITS (AS ON 4th FEBRUARY. 1986 ) - POPULATION CENSUS ORGANISATION ST ATIS TICS DIVISION GOVERNMENT OF PAKISTAN PREFACE The census data is presented in publica tions of each census according to the boundaries of districts, sub-divisions and tehsils/talukas at the t ime of the respective census. But when the data over a period of time is to be examined and analysed it requires to be adjusted fo r the present boundaries, in case of changes in these. It ha s been observed that over the period of last censuses there have been certain c hanges in the boundaries of so me administrative units. It was, therefore, considered advisable that the ce nsus data may be presented according to the boundary position of these areas of some recent date. The census data of all the four censuses of Pakistan have, therefore, been adjusted according to the administ rative units as on 4th February, 1986. The details of these changes have been given at Annexu re- A. Though it would have been preferable to tabulate the whole census data, i.e., population by age , sex, etc., accordingly, yet in view of the very huge work involved even for the 1981 Census and in the absence of availability of source data from the previous three ce nsuses, only population figures have been adjusted. 2. The population of some of the district s and tehsils could no t be worked out clue to non-availability of comparable data of mauzas/dehs/villages comprising these areas. Consequently, their population has been shown against t he district out of which new districts or rehsils were created. -

District Name Department DDO Description Detail Object

District Name Department DDO Description Detail Object Description Budget Estimates 2017-18 Releases Expenditure KD21C09 REVENUE & ESTATE KOHISTAN UPPER KD6108 Deputy Commisioner Kohistan A01101 BASIC PAY 9,184,500 12,316,580 10,833,687 DEPARTMENT KD21C09 REVENUE & ESTATE KOHISTAN UPPER KD6108 Deputy Commisioner Kohistan A01102 PERSONAL PAY 50,000 50,000 - DEPARTMENT KD21C09 REVENUE & ESTATE KOHISTAN UPPER KD6108 Deputy Commisioner Kohistan A01103 SPECIAL PAY 100,000 5,000 - DEPARTMENT KD21C09 REVENUE & ESTATE KOHISTAN UPPER KD6108 Deputy Commisioner Kohistan A01105 QUALIFICATION PAY 50,000 22,250 2,250 DEPARTMENT KD21C09 REVENUE & ESTATE KOHISTAN UPPER KD6108 Deputy Commisioner Kohistan A01151 BASIC PAY 15,629,500 16,706,650 15,067,318 DEPARTMENT KD21C09 REVENUE & ESTATE KOHISTAN UPPER KD6108 Deputy Commisioner Kohistan A01152 PERSONAL PAY 15,000 - - DEPARTMENT KD21C09 REVENUE & ESTATE KOHISTAN UPPER KD6108 Deputy Commisioner Kohistan A01202 HOUSE RENT ALLOWANCE 1,475,000 1,618,520 1,269,132 DEPARTMENT KD21C09 REVENUE & ESTATE KOHISTAN UPPER KD6108 Deputy Commisioner Kohistan A01203 CONVEYANCE ALLOWANCE 3,382,000 3,813,790 3,058,502 DEPARTMENT KD21C09 REVENUE & ESTATE KOHISTAN UPPER KD6108 Deputy Commisioner Kohistan A01207 WASHING ALLOWANCE 19,800 70,800 18,450 DEPARTMENT KD21C09 REVENUE & ESTATE KOHISTAN UPPER KD6108 Deputy Commisioner Kohistan A01208 DRESS ALLOWANCE 12,000 19,600 12,150 DEPARTMENT KD21C09 REVENUE & ESTATE KOHISTAN UPPER KD6108 Deputy Commisioner Kohistan A0120D INTEGRATED ALLOWANCE 92,000 92,000 70,200 DEPARTMENT -

Swat District !

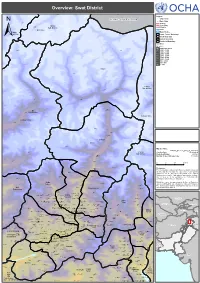

! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Overview: Swat District ! ! ! ! SerkiSerki Chikard Legend ! J A M M U A N D K A S H M I R Citiy / Town ! Main Cities Lohigal Ghari ! Tertiary Secondary Goki Goki Mastuj Shahi!Shahi Sub-division Primary CHITRAL River Chitral Water Bodies Sub-division Union Council Boundary ± Tehsil Boundary District Boundary ! Provincial Boundary Elevation ! In meters ! ! 5,000 and above Paspat !Paspat Kalam 4,000 - 5,000 3,000 - 4,000 ! ! 2,500 - 3,000 ! 2,000 - 2,500 1,500 - 2,000 1,000 - 1,500 800 - 1,000 600 - 800 0 - 600 Kalam ! ! Utror ! ! Dassu Kalam Ushu Sub-division ! Usho ! Kalam Tal ! Utrot!Utrot ! Lamutai Lamutai ! Peshmal!Harianai Dir HarianaiPashmal Kalkot ! ! Sub-division ! KOHISTAN ! ! UPPER DIR ! Biar!Biar ! Balakot Mankial ! Chodgram !Chodgram ! ! Bahrain Mankyal ! ! ! SWAT ! Bahrain ! ! Map Doc Name: PAK078_Overview_Swat_a0_14012010 Jabai ! Pattan Creation Date: 14 Jan 2010 ! ! Sub-division Projection/Datum: Baranial WGS84 !Bahrain BahrainBarania Nominal Scale at A0 paper size: 1:135,000 Ushiri ! Ushiri Madyan ! 0 5 10 15 kms ! ! ! Beshigram Churrai Churarai! Disclaimers: Charri The designations employed and the presentation of material Tirat Sakhra on this map do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Beha ! Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, Bar Thana Darmai Fatehpur city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the Kwana !Kwana delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Kalakot Matta ! Dotted line represents a!pproximately the Line of Control in Miandam Jammu and Kashmir agreed upon by India and Pakistan. Sebujni Patai Olandar Paiti! Olandai! The final status of Jammu and Kashmir has not yet been Gowalairaj Asharay ! Wari Bilkanai agreed upon by the parties. -

Ehsaas Emergency Cash Payments

Consolidated List of Campsites and Bank Branches for Ehsaas Emergency Cash Payments Campsites Ehsaas Emergency Cash List of campsites for biometrically enabled payments in all 4 provinces including GB, AJK and Islamabad AZAD JAMMU & KASHMIR SR# District Name Tehsil Campsite 1 Bagh Bagh Boys High School Bagh 2 Bagh Bagh Boys High School Bagh 3 Bagh Bagh Boys inter college Rera Dhulli Bagh 4 Bagh Harighal BISP Tehsil Office Harigal 5 Bagh Dhirkot Boys Degree College Dhirkot 6 Bagh Dhirkot Boys Degree College Dhirkot 7 Hattain Hattian Girls Degree Collage Hattain 8 Hattain Hattian Boys High School Chakothi 9 Hattain Chakar Boys Middle School Chakar 10 Hattain Leepa Girls Degree Collage Leepa (Nakot) 11 Haveli Kahuta Boys Degree Collage Kahutta 12 Haveli Kahuta Boys Degree Collage Kahutta 13 Haveli Khurshidabad Boys Inter Collage Khurshidabad 14 Kotli Kotli Govt. Boys Post Graduate College Kotli 15 Kotli Kotli Inter Science College Gulhar 16 Kotli Kotli Govt. Girls High School No. 02 Kotli 17 Kotli Kotli Boys Pilot High School Kotli 18 Kotli Kotli Govt. Boys Middle School Tatta Pani 19 Kotli Sehnsa Govt. Girls High School Sehnsa 20 Kotli Sehnsa Govt. Boys High School Sehnsa 21 Kotli Fatehpur Thakyala Govt. Boys Degree College Fatehpur Thakyala 22 Kotli Fatehpur Thakyala Local Govt. Office 23 Kotli Charhoi Govt. Boys High School Charhoi 24 Kotli Charhoi Govt. Boys Middle School Gulpur 25 Kotli Charhoi Govt. Boys Higher Secondary School Rajdhani 26 Kotli Charhoi Govt. Boys High School Naar 27 Kotli Khuiratta Govt. Boys High School Khuiratta 28 Kotli Khuiratta Govt. Girls High School Khuiratta 29 Bhimber Bhimber Govt.