Pak-Swiss INRMP (2010) Study on Timber Harvesting Ban in NWFP

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Floods in Pakistan Pakistan Health Cluster Bulletin No 13 21 August 2010

Floods in Pakistan Pakistan Health Cluster Bulletin No 13 21 August 2010 Vaccination campaign at an IDP camp at Government Girls High School in Taluka Sehwan, Jamshoro district, Sindh province. • Number of reporting disease cases is increasing. Until 18 August, 204 040 of acute diarrhoea, 263 356 cases of skin diseases and 204 647 of acute respiratory have been reported in flood-affected provinces. More than 1.5 million patient consultations have been conducted in flood-affected provinces since 29 July. • Daily number of reported acute diarrhoea cases, monitored since 31 July is rising, particularly in Charsadda, Nowshera and Peshawar. • From 16-18 August, 6 new suspected acute diarrhoea alerts reported from Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KPK). • WHO establishing diarrhoeal treatment centres in flood-affected districts with government and partner support. • Health Cluster to have access to UNHAS flights for delivery of medical items. • Health Cluster coordination active in 5 hubs - Islamabad, Peshawar, Multan, Sukkur, Quetta. • WHO delivers large shipment of medicines to Sukkur coordination hub on 20 August. • In first 3 days of emergency vaccination campaign launched in Peshawar and Charsadda on 16 August, 104 640 children under 5 years were vaccinated against polio. All aged over 6 months (92 269 children) also vaccinated against measles and received vitamin A capsules. • As of 21 August, 39% of the US$56.2 million requested to support the health response has been funded. • According to the National Disaster Management Authority (NDMA), more than 20 million people have been affected by the floods. Almost 1500 people have been reported killed and more than 2000 injured, while around 1 million are left homeless. -

Languages of Kohistan. Sociolinguistic Survey of Northern

SOCIOLINGUISTIC SURVEY OF NORTHERN PAKISTAN VOLUME 1 LANGUAGES OF KOHISTAN Sociolinguistic Survey of Northern Pakistan Volume 1 Languages of Kohistan Volume 2 Languages of Northern Areas Volume 3 Hindko and Gujari Volume 4 Pashto, Waneci, Ormuri Volume 5 Languages of Chitral Series Editor Clare F. O’Leary, Ph.D. Sociolinguistic Survey of Northern Pakistan Volume 1 Languages of Kohistan Calvin R. Rensch Sandra J. Decker Daniel G. Hallberg National Institute of Summer Institute Pakistani Studies of Quaid-i-Azam University Linguistics Copyright © 1992 NIPS and SIL Published by National Institute of Pakistan Studies, Quaid-i-Azam University, Islamabad, Pakistan and Summer Institute of Linguistics, West Eurasia Office Horsleys Green, High Wycombe, BUCKS HP14 3XL United Kingdom First published 1992 Reprinted 2002 ISBN 969-8023-11-9 Price, this volume: Rs.300/- Price, 5-volume set: Rs.1500/- To obtain copies of these volumes within Pakistan, contact: National Institute of Pakistan Studies Quaid-i-Azam University, Islamabad, Pakistan Phone: 92-51-2230791 Fax: 92-51-2230960 To obtain copies of these volumes outside of Pakistan, contact: International Academic Bookstore 7500 West Camp Wisdom Road Dallas, TX 75236, USA Phone: 1-972-708-7404 Fax: 1-972-708-7433 Internet: http://www.sil.org Email: [email protected] REFORMATTING FOR REPRINT BY R. CANDLIN. CONTENTS Preface............................................................................................................viii Maps................................................................................................................. -

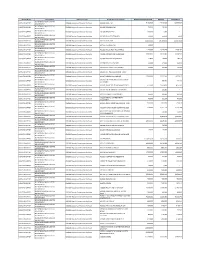

(I) Kabal BAR ABA KHEL 2 78320

Appointment of Teachers (Adhoc School Based) in Elementary & Secondary Education department, Khyber Pakhutunkhwa (Recruitment Test)) Page No.1 Test held on 20th, 26th & 27th November 2016 Final Merit List (PST-Male) Swat NTS Acad:Ma Marks SSC HSSC Bachelor BS Hons. Master M.Phill Diploma M.Ed/MA.Ed rks [out of 100] [Out of 100] Total (H=A+B+ Candidate RollN Date Of 20% 35% 15% 5% 15% Marks [Out Father Name Total 20% (A) Obt Total 20% (B) Obt Total Obt Total Obt Total Obt Total Obt Total Obt Total 5% (G) C+D+E+ Mobile Union Address REMARKS Tehsil Sr Name School Name Obt (I) of 200] o Birth (C) (C) (D) (E) (F) F+G) Name U.C Name apply for J=H+I Council GPS 78320 0347975 BAR ABA VILLAGE AND POST OFFICE SIR SINAI BAR ABA 2 CHINDAKHW AHMAD ALI 1993-5-8 792.0 1050.015.09 795.0 1100.014.45 0.0 0.0 0.0 3409.04300.027.75 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 644.0 900.0 10.73 0.0 0.0 0.0 68.02 63.0 131.02 TAHIR ALI 9647 KHEL TEHSIL KABAL SWAT Kabal KHEL 01098 ARA 78320 0347975 BAR ABA VILLAGE AND POST OFFICE SIR SINAI BAR ABA 3 GPS DERO AHMAD ALI 1993-5-8 792.0 1050.015.09 795.0 1100.014.45 0.0 0.0 0.0 3409.04300.027.75 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 644.0 900.0 10.73 0.0 0.0 0.0 68.02 63.0 131.02 TAHIR ALI 9647 KHEL TEHSIL KABAL SWAT Kabal KHEL 01098 CHUM 78320 0347975 BAR ABA VILLAGE AND POST OFFICE SIR SINAI BAR ABA 3 AHMAD ALI 1993-5-8 792.0 1050.015.09 795.0 1100.014.45 0.0 0.0 0.0 3409.04300.027.75 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 644.0 900.0 10.73 0.0 0.0 0.0 68.02 63.0 131.02 TAHIR ALI 9647 KHEL TEHSIL KABAL SWAT Kabal KHEL 01098 GPS KABAL 78320 0347975 BAR ABA VILLAGE -

Pakistan Water and Power Development Authority

PAKISTAN WATER AND POWER DEVELOPMENT AUTHORITY Public Disclosure Authorized DASU HYDROPOWER PROJECT Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized SOCIAL AND RESETTLEMENT MANAGEMENT PLAN VOLUME 7: PUBLIC HEALTH ACTION PLAN Public Disclosure Authorized General Manager (Hydro) Planning WAPDA, Sunny view, Lahore, Pakistan Final Version 08 March 2014 Social and Resettlement Management Plan Vol. 7 Public Health Action Plan i Dasu Hydropower Project Social and Resettlement Management Plan Vol. 7 Public Health Action Plan SOCIAL AND RESETTLEMENT MANAGEMENT PLAN INDEX OF VOLUMES Volume 1 Executive Summary Volume 2 Socioeconomic Baseline and Impact Assessments Volume 3 Public Consultation and Participation Plan Volume 4 Resettlement Framework Volume 5 Resettlement Action Plan Volume 6 Gender Action Plan Volume 7 Public Health Action Plan Volume 8 Management Plan for Construction-related Impacts Volume 9 Grievances Redress Plan Volume 10 Communications Plan Volume 11 Downstream Fishing Communities: Baseline and Impact Assessments Volume 12 Area Development and Community Support Programs Volume 13 Costs and Budgetary Plan Volume 14 Safeguards Implementation and Monitoring Plan ii Dasu Hydropower Project Social and Resettlement Management Plan Vol. 7 Public Health Action Plan ABBREVIATIONS AFB Acid Fast Bacilli AIDS Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome ANC Antenatal Care ARI Acute Respiratory Tract Infection asl Above Sea Level AWD Acute Watery Diarrhoea BHU Basic Health Unit COI Corridor of Impact CPR Contraceptive Prevalence Rate CSC -

Audit Report on the Accounts of Earthquake Reconstruction & Rehabilitation Authority Audit Year 2015-16

AUDIT REPORT ON THE ACCOUNTS OF EARTHQUAKE RECONSTRUCTION & REHABILITATION AUTHORITY AUDIT YEAR 2015-16 AUDITOR GENERAL OF PAKISTAN TABLE OF CONTENTS ABBREVIATIONS & ACRONYMS ........................................................................... i PREFACE .............................................................................................................. vi EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................................ vii SUMMARY TABLES & CHARTS ..............................................................................1 I Audit Work Statistics ..............................................................................1 II Audit observations regarding Financial Management ...........1 III Outcome Statistics ............................................................................2 IV Table of Irregularities pointed out ..............................................3 V Cost-Benefit ........................................................................................3 CHAPTER-1 Public Financial Management Issues (Earthquake Reconstruction & Rehabilitation Authority 1.1 Audit Paras .............................................................................................4 CHAPTER-2 Earthquake Reconstruction & Rehabilitation Authority (ERRA) 2.1 Introduction of Authority .....................................................................18 2.2 Comments on Budget & Accounts (Variance Analysis) .....................18 2.3 Brief comments on the status of compliance -

DETAILS of Npos, SOCIAL WELFARE DEPARTMENT KHYBER PAKHTUNKHWA (Final Copy)

DETAILS OF NPOs, SOCIAL WELFARE DEPARTMENT KHYBER PAKHTUNKHWA (Final copy) (i) (ii) (iii) (iv) (v) (vi) (vii) (viii) (ix) (x) (xi) (xii) (xiii) (xiv) (xv) (xvi) (xvii) Name, Address & Contact No. Registration No. Sectors/ Target Size Latest Key Functionaries Persons in Effective Name & Value of Associate Bank Donor Means Mode Cross- Recruitme Detail of of NPO with Registering Function Area and Audited Control Moveable & d Entities Account Base of of Fund border nt Criminal Authority s Communit Accounts Immovable (if any) Details Paymen Payme Activiti Capabilitie /Administrati y available Assets (Bank, t nt es s ve Action (Yes /No) Branch & against NPO Account No.) (if any) 1 AAGHOSH WELFARE DSW/NWFP/254 Educatio Peshawar Mediu Yes Education Naseer Ahmad 01 Lack No;. Nil No. NA N.A N.A 07 Nil ORGANIZATION , ISLAMIA 9 n and m 03009399085 PUBLIC SCHOOL 09-03-2006 General aaghosh_2549@yahoo. BHATYAN CHARSADA Welfare com.com ROAD PESHAWAR 2 ABASEEN FOUNDATION DSW/NWFP/169 Educatio Peshawar mediu 2018 Education Dr. Mukhtiar Zaman 80 lac Nil --------- Both Bank Chequ Nil 20 Nil PAK, 3rd Floor, 272 Deans 9 n & m Tel: 0092 91 5603064 e Trade Centre, Peshawar 09.09.2000 health [email protected] Cantonment, Peshawar, . KPK, Pakistan. 3 Ahbab Welfare Organization, DSW/KPK/3490 Health Peshwar Small 2018 Dr. Habib Ullah 06 lac Nil ---------- Self Cash Cash Nil 08 Nil Sikandarpura G.t Rd 16.03.2011 educatio 0334-9099199 help Cheque Chequ n e 4 AIMS PAKISTAN DSW/NWFP/228 Patient’s KPK Mediu 2018 Patient’s Dr. Zia ul hasan 50 Lacs Nil 1721001193 Local Throug Bank Nil Nil 6-A B-3 OPP:Edhi home 9 Diabetic m Diabetic Welfare 0332 5892728, 690001 h Phase #05 Hayatabad 24,03.04 Welfare /Awareness 091-5892728 MIB Cheque Peshawar. -

Revision of Election Electoral Rolls

Changes involved (if DISTRICT TEHSIL QH PC VILLAGE CRCODE NAME DESG PHONE ADDRESS any) i.e. Retirement, Transfer etc 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 SWAT BABUZAI BABUZAI QH QAMBAR PC 0070101 ANWAR ALI SST 03025740801 GHS GOGDARA SWAT BABUZAI BABUZAI QH MINGORA PC 0070102 HAZRAT HUSSAIN CT 03349321527 GHS NO,4 MINGORA SWAT BABUZAI BABUZAI QH SAIDU SHARIF PC 0070103 MUZAFAR HUSSAIN SCT 03449895384 GHS BANR MINGORA SWAT BABUZAI BABUZAI QH MARGHAZAR PC 0070104 SHAMROZ KHAN SST,3 03345652060 GHS CHITOR SWAT BABUZAI BABUZAI QH JAMBIL PC 0070105 ANWAR ULLAH SST 03429209704 GHS KOKARAI SWAT BABUZAI BABUZAI QH KOKARAI PC 0070106 MINHAJ PSHT 03149707774 GPS KOKARAI SWAT BABUZAI BABUZAI QH MANGLAWAR PC 0070107 SAID AKRAM SHAH NULL 03459526902 GPS TOTKAI SWAT BABUZAI BABUZAI QH BISHBANR PC 0070108 ABDUL QAYUM PSHT 03459522939 GPS WARA SAR SWAT BABUZAI BABUZAI QH SARSARDARAY PC 0070109 M. KHALIQ PSHT 03449892194 GPS DIWAN BAT SWAT BABUZAI BABUZAI QH ODIGRAM PC 0070110 ASGHAR KHAN PET 03469411106 GHS TINDODOG SWAT BABUZAI BABUZAI QH ODIGRAM PC 0070110 PARVANAT KHAN HM 03450384634 GHS GOGDARA SWAT BABUZAI MINGORA M.C. CHARGE NO 02 CIRCLE NO 01 0070201 SHER AFZAL KHAN SST NULL GHS NO.1 SWAT BABUZAI MINGORA M.C. CHARGE NO 02 CIRCLE NO 02 0070202 AMIR MOHAMMAD SCT NULL GHSS HAJI BABA SWAT BABUZAI MINGORA M.C. CHARGE NO 02 CIRCLE NO 03 0070203 ZAHID KHAN SCT NULL GHSS HAJI BABA SWAT BABUZAI MINGORA M.C. CHARGE NO 02 CIRCLE NO 04 0070204 MUHAMMAD RAHIM SST NULL GHS NO.1 MINGORA SWAT BABUZAI MINGORA M.C. -

765Kv Dasu Transmission Line Project Resettlement Action Plan (Rap)

GOVERNMENT OF PAKISTAN MINISTRY OF ENERGY (POWER DIVISION) NATIONAL TRANSMISSION & DISPATCH COMPANY (NTDC) 765KV DASU TRANSMISSION LINE PROJECT RESETTLEMENT ACTION PLAN (RAP) November 2019 National Transmission & Despatch Company Ministry of Energy (Power Division) Government of Pakistan National Transmission & Despatch Company TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 BACKGROUND ........................................................................................................................................... 1 1.2 PROJECT DESCRIPTION AND COMPONENTS ...................................................................................................... 1 1.2.1 Project Description and Components ................................................................................................ 1 1.2.2 Access Tracks and Roads ................................................................................................................... 3 1.2.3 Construction Methodology ............................................................................................................... 4 1.2.4 Project Cost and Construction Time .................................................................................................. 6 1.3 THE PROJECT AREA .................................................................................................................................... 6 1.4 PROJECT BENEFITS AND IMPACTS -

PAK102 Revision 2 for Approval 16September 2010

SECRETARIAT 150 route de Ferney, P.O. Box 2100, 1211 Geneva 2, Switzerland TEL: +41 22 791 6033 FAX: +41 22 791 6506 www .actalliance.org Appeal Pakistan Pakistan Floods Emergency (PAK102) – Rev. 2 Appeal Target: US$ 12,441,347 Balance Requested: US$ 6,478,821 Geneva, 17 September 2010 Dear colleagues, Since 21 July 2010, heavy monsoon rains have led to the worst flooding in Pakistan’s history. Please see the ACT website ( www.actalliance.org/resources/alertsandsitreps ) for the latest ACT Situation Reports from Pakistan on this fast changing emergency. The members of the ACT Pakistan Forum, Church World Service- Pakistan/Afghanistan (CWS-P/A), Norwegian Church Aid (NCA), and Diakonie Katastrophenhilfe (DKH) continue to distribute urgent relief assistance to the flood-affected communities with the financial, material aid and personnel support of many international ACT members, their national constituencies and institutional donors, as well as other supporters from around the world. This ACT appeal was first issued on 4 August and then replaced by a revised version issued on 11 August to include the proposed responses of DKH and NCA, as well as a scaled-up version of the CWS-P/A programme. This second revision of the appeal significantly scales-up the entire proposed programme from a previous funding target of US $4,101,731 to US$ 12,441,347. CWS P/A is increasing the number of operational areas to include Sukkur and Thatta Districts in Sindh Province and Muzaffargarh District in Punjab Province. CWS P/A is now working with an additional partner – the Church of Pakistan (CoP) Diocese of Raiwind. -

Forestry in the Princely State of Swat and Kalam (North-West Pakistan)

Forestry in the Princely State of Swat and Kalam (North-West Pakistan) A Historical Perspective on Norms and Practices IP6 Working Paper No.6 Sultan-i-Rome, Ph.D. 2005 Forestry in the Princely State of Swat and Kalam (North-West Pakistan) A Historical Perspective on Norms and Practices IP6 Working Paper No.6 Sultan-i-Rome, Ph.D. 2005 The Swiss National Centre of Competence in Research (NCCR) North-South is based on a network of partnerships with research institutions in the South and East, focusing on the analysis and mitigation of syndromes of global change and globalisation. Its sub-group named IP6 focuses on institutional change and livelihood strategies: State policies as well as other regional and international institutions – which are exposed to and embedded in national economies and processes of globalisation and global change – have an impact on local people's livelihood practices and strategies as well as on institutions developed by the people themselves. On the other hand, these institutionally shaped livelihood activities have an impact on livelihood outcomes and the sustainability of resource use. Understanding how the micro- and macro-levels of this institutional context interact is of vital importance for developing sustainable local natural resource management as well as supporting local livelihoods. For an update of IP6 activities see http://www.nccr-north-south.unibe.ch (>Individual Projects > IP6) The IP6 Working Paper Series presents preliminary research emerging from IP6 for discussion and critical comment. Author Sultan-i-Rome, Ph.D. Village & Post Office Hazara, Tahsil Kabal, Swat–19201, Pakistan e-mail: [email protected] Distribution A Downloadable pdf version is availale at www.nccr- north-south.unibe.ch (-> publications) Cover Photo The Swat Valley with Mingawara, and Upper Swat in the background (photo Urs Geiser) All rights reserved with the author. -

District Name Department DDO Description Detail Object

District Name Department DDO Description Detail Object Description Budget Estimates 2017-18 Releases Expenditure KD21C09 REVENUE & ESTATE KOHISTAN UPPER KD6108 Deputy Commisioner Kohistan A01101 BASIC PAY 9,184,500 12,316,580 10,833,687 DEPARTMENT KD21C09 REVENUE & ESTATE KOHISTAN UPPER KD6108 Deputy Commisioner Kohistan A01102 PERSONAL PAY 50,000 50,000 - DEPARTMENT KD21C09 REVENUE & ESTATE KOHISTAN UPPER KD6108 Deputy Commisioner Kohistan A01103 SPECIAL PAY 100,000 5,000 - DEPARTMENT KD21C09 REVENUE & ESTATE KOHISTAN UPPER KD6108 Deputy Commisioner Kohistan A01105 QUALIFICATION PAY 50,000 22,250 2,250 DEPARTMENT KD21C09 REVENUE & ESTATE KOHISTAN UPPER KD6108 Deputy Commisioner Kohistan A01151 BASIC PAY 15,629,500 16,706,650 15,067,318 DEPARTMENT KD21C09 REVENUE & ESTATE KOHISTAN UPPER KD6108 Deputy Commisioner Kohistan A01152 PERSONAL PAY 15,000 - - DEPARTMENT KD21C09 REVENUE & ESTATE KOHISTAN UPPER KD6108 Deputy Commisioner Kohistan A01202 HOUSE RENT ALLOWANCE 1,475,000 1,618,520 1,269,132 DEPARTMENT KD21C09 REVENUE & ESTATE KOHISTAN UPPER KD6108 Deputy Commisioner Kohistan A01203 CONVEYANCE ALLOWANCE 3,382,000 3,813,790 3,058,502 DEPARTMENT KD21C09 REVENUE & ESTATE KOHISTAN UPPER KD6108 Deputy Commisioner Kohistan A01207 WASHING ALLOWANCE 19,800 70,800 18,450 DEPARTMENT KD21C09 REVENUE & ESTATE KOHISTAN UPPER KD6108 Deputy Commisioner Kohistan A01208 DRESS ALLOWANCE 12,000 19,600 12,150 DEPARTMENT KD21C09 REVENUE & ESTATE KOHISTAN UPPER KD6108 Deputy Commisioner Kohistan A0120D INTEGRATED ALLOWANCE 92,000 92,000 70,200 DEPARTMENT -

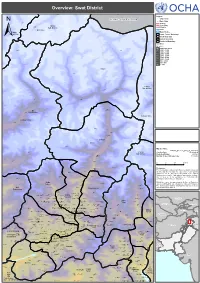

Swat District !

! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Overview: Swat District ! ! ! ! SerkiSerki Chikard Legend ! J A M M U A N D K A S H M I R Citiy / Town ! Main Cities Lohigal Ghari ! Tertiary Secondary Goki Goki Mastuj Shahi!Shahi Sub-division Primary CHITRAL River Chitral Water Bodies Sub-division Union Council Boundary ± Tehsil Boundary District Boundary ! Provincial Boundary Elevation ! In meters ! ! 5,000 and above Paspat !Paspat Kalam 4,000 - 5,000 3,000 - 4,000 ! ! 2,500 - 3,000 ! 2,000 - 2,500 1,500 - 2,000 1,000 - 1,500 800 - 1,000 600 - 800 0 - 600 Kalam ! ! Utror ! ! Dassu Kalam Ushu Sub-division ! Usho ! Kalam Tal ! Utrot!Utrot ! Lamutai Lamutai ! Peshmal!Harianai Dir HarianaiPashmal Kalkot ! ! Sub-division ! KOHISTAN ! ! UPPER DIR ! Biar!Biar ! Balakot Mankial ! Chodgram !Chodgram ! ! Bahrain Mankyal ! ! ! SWAT ! Bahrain ! ! Map Doc Name: PAK078_Overview_Swat_a0_14012010 Jabai ! Pattan Creation Date: 14 Jan 2010 ! ! Sub-division Projection/Datum: Baranial WGS84 !Bahrain BahrainBarania Nominal Scale at A0 paper size: 1:135,000 Ushiri ! Ushiri Madyan ! 0 5 10 15 kms ! ! ! Beshigram Churrai Churarai! Disclaimers: Charri The designations employed and the presentation of material Tirat Sakhra on this map do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Beha ! Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, Bar Thana Darmai Fatehpur city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the Kwana !Kwana delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Kalakot Matta ! Dotted line represents a!pproximately the Line of Control in Miandam Jammu and Kashmir agreed upon by India and Pakistan. Sebujni Patai Olandar Paiti! Olandai! The final status of Jammu and Kashmir has not yet been Gowalairaj Asharay ! Wari Bilkanai agreed upon by the parties.