Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Reconstruction Program: Mid-Term Performance Evaluation Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

HEALTH CLUSTER PAKISTAN Crisis in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Issue No 4

HEALTH CLUSTER PAKISTAN Crisis in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Issue No 4 20 March‐12 April, 2010 • As of 15 April, 300,468 individuals or 42 924 families are living with host communities in Hangu (15187 families,106 309 individuals) Peshawar(1910 families,13370 individuals) and Kohat(25827 families,180789 individuals) Districts, displaced from Orakzai and Kurram Agency, of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province formally known as North West Frontier Province (NWFP). • In addition to above there are 2 33 688 families or 1 404 241 people are living outside camps with host communities in Mardan, Swabi, Charssada, Pakistan IDPs living in camps and Host Nowshera,Kohat, Hangu Tank, communities DIKhan, Peshawar Abbotabad, Haripur, Mansehra and Battagram districts of NWFP. There are 23 784 families or 121 760 individuals living in camps of Charssada, Nowsehra, Lower Dir, Hangu and Malakand districts (Source: Commissionerate for Afghan Refugees and National Data Base Authority) • In order to cater for the health sector needs, identified through recent health assessment conducted by health cluster partners, in Kohat and Hangu districts due to ongoing military operation in Orakzai Agency, Health cluster partners ( 2 UN and 8 I/NGO’s have received 2.4 million dollars fund from Central Emergency Response Fund (CERF). This fund will shoulder the ongoing health response for the IDPs and host communities living in Kohat and Hangu Districts 499 DEWS health facilities reported 133 426 consultations from 20-26 March, of which 76 909 (58 %) were reported for female consultations and 56 517 (42%) for male. Children aged under 5 years represented 33 972 (25%) of all consultations. -

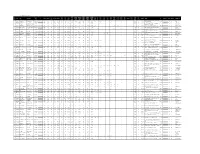

District Cadre SST Posts by Directorate of Elementary and Secondary Education, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Peshawar (Screening Test)

District Cadre SST Posts by Directorate of Elementary and Secondary Education, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Peshawar (Screening Test) Test held on 4th December 2016 Provisional Merit List For Interview Swat Male SST (General) SSC Sr RollNo Name NIC Gender Domicile Obt Name of school apply for 1 783001235 BARKAT ALI 15602-4130615-9 MALE SWAT 609.0 GHS SHINKOO 1 783001235 BARKAT ALI 15602-4130615-9 MALE SWAT 609.0 GHSS KALAM 1 783001235 BARKAT ALI 15602-4130615-9 MALE SWAT 609.0 GHSS MANKYAL 1 783001235 BARKAT ALI 15602-4130615-9 MALE SWAT 609.0 GHSS SAKHRA 1 783001235 BARKAT ALI 15602-4130615-9 MALE SWAT 609.0 GMS BASHIGRAM 1 783001083 USAMA AZEEM 15601-7397921-5 MALE SWAT 579.0 GHS GAT 2 783001083 USAMA AZEEM 15601-7397921-5 MALE SWAT 579.0 GHSS SAKHRA District Cadre SST Posts by Directorate of Elementary and Secondary Education, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Peshawar (Screening Test) Test held on 4th December 2016 Provisional Merit List For Interview Swat Male SST (General) SSC HSSC Bachelor BS Hons. Master 15 Total 20% (A) Obt Total 20% (B) Obt Total 20% (C) Obt Total 35% (C) Obt Total % (D) 900.0 13.53 780.0 1100.0 14.18 316.0 550.0 11.49 0.0 0.0 0.0 614.0 1100.0 8.37 900.0 13.53 780.0 1100.0 14.18 316.0 550.0 11.49 0.0 0.0 0.0 614.0 1100.0 8.37 900.0 13.53 780.0 1100.0 14.18 316.0 550.0 11.49 0.0 0.0 0.0 614.0 1100.0 8.37 900.0 13.53 780.0 1100.0 14.18 316.0 550.0 11.49 0.0 0.0 0.0 614.0 1100.0 8.37 900.0 13.53 780.0 1100.0 14.18 316.0 550.0 11.49 0.0 0.0 0.0 614.0 1100.0 8.37 850.0 13.62 867.0 1400.0 12.39 2370.0 3400.0 13.94 0.0 0.0 0.0 745.0 1000.0 -

(I) Kabal BAR ABA KHEL 2 78320

Appointment of Teachers (Adhoc School Based) in Elementary & Secondary Education department, Khyber Pakhutunkhwa (Recruitment Test)) Page No.1 Test held on 20th, 26th & 27th November 2016 Final Merit List (PST-Male) Swat NTS Acad:Ma Marks SSC HSSC Bachelor BS Hons. Master M.Phill Diploma M.Ed/MA.Ed rks [out of 100] [Out of 100] Total (H=A+B+ Candidate RollN Date Of 20% 35% 15% 5% 15% Marks [Out Father Name Total 20% (A) Obt Total 20% (B) Obt Total Obt Total Obt Total Obt Total Obt Total Obt Total 5% (G) C+D+E+ Mobile Union Address REMARKS Tehsil Sr Name School Name Obt (I) of 200] o Birth (C) (C) (D) (E) (F) F+G) Name U.C Name apply for J=H+I Council GPS 78320 0347975 BAR ABA VILLAGE AND POST OFFICE SIR SINAI BAR ABA 2 CHINDAKHW AHMAD ALI 1993-5-8 792.0 1050.015.09 795.0 1100.014.45 0.0 0.0 0.0 3409.04300.027.75 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 644.0 900.0 10.73 0.0 0.0 0.0 68.02 63.0 131.02 TAHIR ALI 9647 KHEL TEHSIL KABAL SWAT Kabal KHEL 01098 ARA 78320 0347975 BAR ABA VILLAGE AND POST OFFICE SIR SINAI BAR ABA 3 GPS DERO AHMAD ALI 1993-5-8 792.0 1050.015.09 795.0 1100.014.45 0.0 0.0 0.0 3409.04300.027.75 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 644.0 900.0 10.73 0.0 0.0 0.0 68.02 63.0 131.02 TAHIR ALI 9647 KHEL TEHSIL KABAL SWAT Kabal KHEL 01098 CHUM 78320 0347975 BAR ABA VILLAGE AND POST OFFICE SIR SINAI BAR ABA 3 AHMAD ALI 1993-5-8 792.0 1050.015.09 795.0 1100.014.45 0.0 0.0 0.0 3409.04300.027.75 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 644.0 900.0 10.73 0.0 0.0 0.0 68.02 63.0 131.02 TAHIR ALI 9647 KHEL TEHSIL KABAL SWAT Kabal KHEL 01098 GPS KABAL 78320 0347975 BAR ABA VILLAGE -

Genetic Analysis of the Major Tribes of Buner and Swabi Areas Through Dental Morphology and Dna Analysis

GENETIC ANALYSIS OF THE MAJOR TRIBES OF BUNER AND SWABI AREAS THROUGH DENTAL MORPHOLOGY AND DNA ANALYSIS MUHAMMAD TARIQ DEPARTMENT OF GENETICS HAZARA UNIVERSITY MANSEHRA 2017 I HAZARA UNIVERSITY MANSEHRA Department of Genetics GENETIC ANALYSIS OF THE MAJOR TRIBES OF BUNER AND SWABI AREAS THROUGH DENTAL MORPHOLOGY AND DNA ANALYSIS By Muhammad Tariq This research study has been conducted and reported as partial fulfillment of the requirements of PhD degree in Genetics awarded by Hazara University Mansehra, Pakistan Mansehra The Friday 17, February 2017 I ABSTRACT This dissertation is part of the Higher Education Commission of Pakistan (HEC) funded project, “Enthnogenetic elaboration of KP through Dental Morphology and DNA analysis”. This study focused on five major ethnic groups (Gujars, Jadoons, Syeds, Tanolis, and Yousafzais) of Buner and Swabi Districts, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Province, Pakistan, through investigations of variations in morphological traits of the permanent tooth crown, and by molecular anthropology based on mitochondrial and Y-chromosome DNA analyses. The frequencies of seven dental traits, of the Arizona State University Dental Anthropology System (ASUDAS) were scored as 17 tooth- trait combinations for each sample, encompassing a total sample size of 688 individuals. These data were compared to data collected in an identical fashion among samples of prehistoric inhabitants of the Indus Valley, southern Central Asia, and west-central peninsular India, as well as to samples of living members of ethnic groups from Abbottabad, Chitral, Haripur, and Mansehra Districts, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and to samples of living members of ethnic groups residing in Gilgit-Baltistan. Similarities in dental trait frequencies were assessed with C.A.B. -

Audit Report on the Accounts of Assistant Director

AUDIT REPORT ON THE ACCOUNTS OF ASSISTANT DIRECTOR LOCAL GOVERNMENT ELECTIONS & RURAL DEVELOPMENT DEPARTMENT AND SELECTED VILLAGE COUNCILS / NEIGHBORHOOD COUNCILS DISTRICT SWAT KHYBER PAKHTUNKHWA AUDIT YEAR 2016-17 AUDITOR GENERAL OF PAKISTAN TABLE OF CONTENTS ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS ......................................................................... i Preface .............................................................................................................................. ii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................. iii SUMMARY TABLES AND CHARTS ......................................................................... vii I: Audit Work Statistics ........................................................................................... vii II: Audit observations classified by Categories ........................................................ vii III: Outcome Statistics .............................................................................................viii IV: Irregularities pointed out ..................................................................................... ix V: Cost-Benefit ........................................................................................................ ix CHAPTER-1 .................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Assistant Director LGE&RDD and NCs/VCs District Swat ..................................... 1 1.1.1 Introduction -

HEALTH CLUSTER PAKISTAN Crisis in NWFP WEEKLY BULLETIN No

HEALTH CLUSTER PAKISTAN Crisis in NWFP WEEKLY BULLETIN No 12 9 September 2009 HIGHLIGHTS • The IDP return process continues. Health Cluster partners are moving forward with health interventions in the districts of Swat, Buner, Lower Dir and Upper Dir while continuing to support IDPs who remain in the camps. To date, a total of 235 159 families have returned to their respective districts. (Source: PDMA/PaRRSA.) • The latest data from the National Database Registration Authority (NADRA) show there has been an influx of returnees in Waziristan. A total of 17 375 families, including 8281 in D.I. Khan District and 2756 in Tank District, have registered. Maternal, neonatal and and child health remains a priority among health interventions in NWFP • An assessment of health facilities in D.I. Khan was completed on 28 August. The report is being finalized and will be shared shortly. An assessment of health facilities in Swat district will begin on 13 September. • Between 22 and 28 August, a total of 69 892 consultations were reported from 226 disease surveillance sentinel sites in NWFP. This represents a 7% decrease compared to the number of consultations registered the previous week. • Seventeen DEWS sites reported 546 antenatal visits between 22 and 28 August. Data from UNFPA’s seven maternal, neonatal and child health (MNCH) care service delivery points in Lower Dir, Nowshera, Charsadda and Mardan districts showed an overall 16% increase in patient consultations in government and in-camp health facilities. However, postnatal consultations decreased from 48 to 35, and deliveries dropped from 18 to 10 at MNCH clinics. -

FATA and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa

Nutrition Presence of Partners - F.A.T.A. and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 29 November 2010 Legend CHITRAL Provincial Boundar Kalam Utror District Boundary Number of Implementing Partners KOHISTAN Balakot 1 2 SWAT Mankyal UPPER DIR Bahrain 3 Gowalairaj Madyan PESHAWAR Beshigram Beha Sakhra Bar Thana Fatehpur Gail Maidan Zaimdara Asharay Darangal Baidara Bishgram ShawarChuprial Miskana Shalpin Urban-4 Lal Qila Tall Arkot Shahpur Usterzai Samar Bagh Lijbook Jano/chamtalai Muhammad Zai Mayar Kala Kalay Alpuri Kuz Kana Urban-3 Koto Pir Kalay Munjai Shah DehraiDewlai Urban-5 Mian Kili Balambat Bara Bandai SHANGLADherai Opal Rabat Totano Bandai Kech Banda Togh Bala Munda QalaKhazanaBandagai HazaraKanaju Malik Khel Chakesar Urban-6 Kotigram Asbanr Puran Ganjiano Kalli Raisan Shah Pur Bahadar Kot 1 LOWER DIRMc Timargara Koz Abakhel Kabal BATAGRAM Khanpur Billitang Ziarat Talash Aloch HANGU Ouch Kokarai Kharmatu Bagh Dush Khel Chakdara Islampur Kotki KOHAT Khadagzai AbazaiBadwan Sori Chagharzai Gul BandaiBehlool Khail Kota Dhoda Daggar Batara MALAKAND Pandher Rega MANSEHRA BUNER Krapa Gagra Norezai KARAK MARDAN CHARSADDA Kangra Rajjar IiShakho KYBER PAKHTUNKHWA Hisar Yasinzai Dosahra Nisatta Dheri Zardad SWABI ABBOTTABAD Mohib Banda ChowkaiAman Kot M.c Pabbi HARIPUR PESHAWAR NOWSHERA Shah Kot Usterzai Urban-4 Kech Banda Urban-6Togh Bala Raisan Khan Bari Shah Pur Kotki KharmatuBillitang KOHAT HANGU Dhoda Muhammad Khawja This map illustrates the presence of organisations working in the sector of Nutrition in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and FATA as reported by relief -

DETAILS of Npos, SOCIAL WELFARE DEPARTMENT KHYBER PAKHTUNKHWA (Final Copy)

DETAILS OF NPOs, SOCIAL WELFARE DEPARTMENT KHYBER PAKHTUNKHWA (Final copy) (i) (ii) (iii) (iv) (v) (vi) (vii) (viii) (ix) (x) (xi) (xii) (xiii) (xiv) (xv) (xvi) (xvii) Name, Address & Contact No. Registration No. Sectors/ Target Size Latest Key Functionaries Persons in Effective Name & Value of Associate Bank Donor Means Mode Cross- Recruitme Detail of of NPO with Registering Function Area and Audited Control Moveable & d Entities Account Base of of Fund border nt Criminal Authority s Communit Accounts Immovable (if any) Details Paymen Payme Activiti Capabilitie /Administrati y available Assets (Bank, t nt es s ve Action (Yes /No) Branch & against NPO Account No.) (if any) 1 AAGHOSH WELFARE DSW/NWFP/254 Educatio Peshawar Mediu Yes Education Naseer Ahmad 01 Lack No;. Nil No. NA N.A N.A 07 Nil ORGANIZATION , ISLAMIA 9 n and m 03009399085 PUBLIC SCHOOL 09-03-2006 General aaghosh_2549@yahoo. BHATYAN CHARSADA Welfare com.com ROAD PESHAWAR 2 ABASEEN FOUNDATION DSW/NWFP/169 Educatio Peshawar mediu 2018 Education Dr. Mukhtiar Zaman 80 lac Nil --------- Both Bank Chequ Nil 20 Nil PAK, 3rd Floor, 272 Deans 9 n & m Tel: 0092 91 5603064 e Trade Centre, Peshawar 09.09.2000 health [email protected] Cantonment, Peshawar, . KPK, Pakistan. 3 Ahbab Welfare Organization, DSW/KPK/3490 Health Peshwar Small 2018 Dr. Habib Ullah 06 lac Nil ---------- Self Cash Cash Nil 08 Nil Sikandarpura G.t Rd 16.03.2011 educatio 0334-9099199 help Cheque Chequ n e 4 AIMS PAKISTAN DSW/NWFP/228 Patient’s KPK Mediu 2018 Patient’s Dr. Zia ul hasan 50 Lacs Nil 1721001193 Local Throug Bank Nil Nil 6-A B-3 OPP:Edhi home 9 Diabetic m Diabetic Welfare 0332 5892728, 690001 h Phase #05 Hayatabad 24,03.04 Welfare /Awareness 091-5892728 MIB Cheque Peshawar. -

Contesting Candidates NA-1 Peshawar-I

Form-V: List of Contesting Candidates NA-1 Peshawar-I Serial No Name of contestng candidate in Address of contesting candidate Symbol Urdu Alphbeticl order Allotted 1 Sahibzada PO Ashrafia Colony, Mohala Afghan Cow Colony, Peshawar Akram Khan 2 H # 3/2, Mohala Raza Shah Shaheed Road, Lantern Bilour House, Peshawar Alhaj Ghulam Ahmad Bilour 3 Shangar PO Bara, Tehsil Bara, Khyber Agency, Kite Presented at Moh. Gul Abad, Bazid Khel, PO Bashir Ahmad Afridi Badh Ber, Distt Peshawar 4 Shaheen Muslim Town, Peshawar Suitcase Pir Abdur Rehman 5 Karim Pura, H # 282-B/20, St 2, Sheikhabad 2, Chiragh Peshawar (Lamp) Jan Alam Khan Paracha 6 H # 1960, Mohala Usman Street Warsak Road, Book Peshawar Haji Shah Nawaz 7 Fazal Haq Baba Yakatoot, PO Chowk Yadgar, H Ladder !"#$%&'() # 1413, Peshawar Hazrat Muhammad alias Babo Maavia 8 Outside Lahore Gate PO Karim Pura, Peshawar BUS *!+,.-/01!234 Khalid Tanveer Rohela Advocate 9 Inside Yakatoot, PO Chowk Yadgar, H # 1371, Key 5 67'8 Peshawar Syed Muhammad Sibtain Taj Agha 10 H # 070, Mohala Afghan Colony, Peshawar Scale 9 Shabir Ahmad Khan 11 Chamkani, Gulbahar Colony 2, Peshawar Umbrella :;< Tariq Saeed 12 Rehman Housing Society, Warsak Road, Fist 8= Kababiyan, Peshawar Amir Syed Monday, April 22, 2013 6:00:18 PM Contesting candidates Page 1 of 176 13 Outside Lahori Gate, Gulbahar Road, H # 245, Tap >?@A= Mohala Sheikh Abad 1, Peshawar Aamir Shehzad Hashmi 14 2 Zaman Park Zaman, Lahore Bat B Imran Khan 15 Shadman Colony # 3, Panal House, PO Warsad Tiger CDE' Road, Peshawar Muhammad Afzal Khan Panyala 16 House # 70/B, Street 2,Gulbahar#1,PO Arrow FGH!I' Gulbahar, Peshawar Muhammad Zulfiqar Afghani 17 Inside Asiya Gate, Moh. -

Revision of Election Electoral Rolls

Changes involved (if DISTRICT TEHSIL QH PC VILLAGE CRCODE NAME DESG PHONE ADDRESS any) i.e. Retirement, Transfer etc 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 SWAT BABUZAI BABUZAI QH QAMBAR PC 0070101 ANWAR ALI SST 03025740801 GHS GOGDARA SWAT BABUZAI BABUZAI QH MINGORA PC 0070102 HAZRAT HUSSAIN CT 03349321527 GHS NO,4 MINGORA SWAT BABUZAI BABUZAI QH SAIDU SHARIF PC 0070103 MUZAFAR HUSSAIN SCT 03449895384 GHS BANR MINGORA SWAT BABUZAI BABUZAI QH MARGHAZAR PC 0070104 SHAMROZ KHAN SST,3 03345652060 GHS CHITOR SWAT BABUZAI BABUZAI QH JAMBIL PC 0070105 ANWAR ULLAH SST 03429209704 GHS KOKARAI SWAT BABUZAI BABUZAI QH KOKARAI PC 0070106 MINHAJ PSHT 03149707774 GPS KOKARAI SWAT BABUZAI BABUZAI QH MANGLAWAR PC 0070107 SAID AKRAM SHAH NULL 03459526902 GPS TOTKAI SWAT BABUZAI BABUZAI QH BISHBANR PC 0070108 ABDUL QAYUM PSHT 03459522939 GPS WARA SAR SWAT BABUZAI BABUZAI QH SARSARDARAY PC 0070109 M. KHALIQ PSHT 03449892194 GPS DIWAN BAT SWAT BABUZAI BABUZAI QH ODIGRAM PC 0070110 ASGHAR KHAN PET 03469411106 GHS TINDODOG SWAT BABUZAI BABUZAI QH ODIGRAM PC 0070110 PARVANAT KHAN HM 03450384634 GHS GOGDARA SWAT BABUZAI MINGORA M.C. CHARGE NO 02 CIRCLE NO 01 0070201 SHER AFZAL KHAN SST NULL GHS NO.1 SWAT BABUZAI MINGORA M.C. CHARGE NO 02 CIRCLE NO 02 0070202 AMIR MOHAMMAD SCT NULL GHSS HAJI BABA SWAT BABUZAI MINGORA M.C. CHARGE NO 02 CIRCLE NO 03 0070203 ZAHID KHAN SCT NULL GHSS HAJI BABA SWAT BABUZAI MINGORA M.C. CHARGE NO 02 CIRCLE NO 04 0070204 MUHAMMAD RAHIM SST NULL GHS NO.1 MINGORA SWAT BABUZAI MINGORA M.C. -

District Buner Adp 2020-21

Project Description Budget BD15D00166-check 10 BD15D00370-Pipe Water Channel UC Gulbandi 330,000 BD15D00371-WSS at UC Gulbandai 635,358 BD15D00389-Pressure Pump/Hand pump Nawagai-1 Hujra 111Akazai 213,032 BD15D00390-Pressure Pump/Hand pump Nawagai-2Bolagat 118,078 BD15D00391-Pressure Pump/Hand pump Nawagai-2 RahmatSaid 284,885 BD15D00392-Pressure Pump/Hand pump Nawagai-1 380,724 BD15D00393-Pressure Pump/Hand pump Makhranai Dandmaira Nasib 215,937 BD15D00394-Pressure Pump/Hand pump sora 257,749 BD15D00407-RAHIM PATAY ROAD 0 BD15D00409-"PRESSURE PUMP/HAND PUMP,WASH ROOM &REPAIR OF ROAD IN DISPENSORY AT CHANGLAI" 0 BD15D00430-WSS AT SOLAI CHUM & SANITATION AT KANDAWMASJED & RAHMAT KOROONA VC ELAI-1 173,000 BD15D00436-REPAIR OF BHU GAGRA 0 BD15D00469-CONSTRUCTION OF BOUNDRY WALL AT TOTYANOKALAY JANAZGAH 100,000 BD15D00472-INTEZARGAH AT NOREZE (AZMAT BIBI) 670,000 BD15D00474-INSTALLATION OF SOLAR ENRGY SYSTEM ANDHAND PUMP AT GMS SHARGHASHI BATAI 163,227 BD15D00475-INSTALLATION OF SOLAR ENRGY SYSTEM ANDHAND PUMP AT GHS BATAI 0 BD15D00477-REPAIR AND MAINTENANCE OF TEHSIL HEADQUARTER HOSPITAL 1,710,928 BD15D00486-INSTALLATION OF SOLAR SYSTEM IN GHSSAWARAI 0 BD15D00496-PCC PATHWAY ROAD GHS INZAR MIRA 140,712 BD15D00505-"HAND PUMPS AT MOHALLA SARGANTAL,MUGHALBARKHAN & MOMIN USTAD WARD TORWARSAK" 49,596 BD15D00513-REPAIR AND MAINTANANCE/ SOLAR SYSTEMGGmS GADEZI 894,157 BD15D00520-Pressure Pump at GHS Khanano Dherai 127,636 BD15D00521-Hand Pump at GHS Jangai & GGHS Kadal 500,000 BD15D00541-Protection Wall Khananu Dherai Wand UCMakhranai 330,000 BD16D00030-WSS -

FTS at Merit List Male Swat Serial No Roll No Name Father Name Date Of

FTS AT Merit list Male Swat Bachelor Bachelor Bachelor Bachelor Bachelor Bachelor M.Phil/ Total Serial Date of SSC HSSC HSSC HSSC (14 (16 Years) / (16 Years) / (16 Years) / B.Ed B.Ed B.Ed M.Ed M.Ed M.Ed M.Phil/ M.Phil/ PhD PhD FTS Roll No Name Father Name NIC Gender Domicile SSC Total SSC Score (14 Years) (14 Years) MS PhD Total ACAD TotalScore Address City Mobile No Religion Disability Candidate UC No Birth Obtain Obtain Total Score Years) Master Master Master Obtain Total Score Obtain Total Score MS Total MS Score Obtain Score Marks Total Score Obtain Score Obtain Obtain Total Score PLOT NO 106/07 SEC 6 E LERP HAWKS BOY SCHEME 1 40465823 HAFIZ AIJAZ ALI MUHAMMAD ALI 11/18/1986 ############## Male Swat 524 850 12.329 701 1100 12.745 662 1000 13.24 695 1000 13.9 600 900 3.333 3.4 4 4.25 304 400 3.8 0 63.597 68 131.597 KARACHI ############# Muslim No KOTA 42 MUSHARRAF COLONY 2 40465697 SAEED UR REHMAN ABDUL WAHAR 2/20/1990 ############## Male Swat 529 800 13.225 521 1100 9.473 279 550 10.145 631 1100 11.473 0 0 0 0 44.316 86 130.316 VILLAGE AND PO SAKHRA MATTA Swat ############# N/A No SAKHRA MATTA TEHSIL TAKHT BHAI P/O LUND KHWAR JAMMIA 3 40125383 DAWOOD ALI MOHAMMAD RASHAD 3/1/1990 ############## Male Swat 830 1050 15.81 794 1100 14.436 344 550 12.509 481 600 16.033 599 900 3.328 0 0 0 62.116 68 130.116 Mardan ############# Muslim No KOZ ABA KHEL ISLAMIA MOHALA HOTI KHER MUHALLA MAZID KHEL NEAR SUNEHRI MASJID 4 40465683 FARHAD KHAN HABIB ULLAH KHAN 5/25/1993 ############## Male Swat 742 1050 14.133 739 1100 13.436 640 1000 12.8 1081