Are Divergent Preferences Between Benefactors and Beneficiaries an Obstacle to Community-Based Conservation?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dasu Hydropower Project

Public Disclosure Authorized PAKISTAN WATER AND POWER DEVELOPMENT AUTHORITY (WAPDA) Public Disclosure Authorized Dasu Hydropower Project ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL ASSESSMENT Public Disclosure Authorized EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Report by Independent Environment and Social Consultants Public Disclosure Authorized April 2014 Contents List of Acronyms .................................................................................................................iv 1. Introduction ...................................................................................................................1 1.1. Background ............................................................................................................. 1 1.2. The Proposed Project ............................................................................................... 1 1.3. The Environmental and Social Assessment ............................................................... 3 1.4. Composition of Study Team..................................................................................... 3 2. Policy, Legal and Administrative Framework ...............................................................4 2.1. Applicable Legislation and Policies in Pakistan ........................................................ 4 2.2. Environmental Procedures ....................................................................................... 5 2.3. World Bank Safeguard Policies................................................................................ 6 2.4. Compliance Status with -

Languages of Kohistan. Sociolinguistic Survey of Northern

SOCIOLINGUISTIC SURVEY OF NORTHERN PAKISTAN VOLUME 1 LANGUAGES OF KOHISTAN Sociolinguistic Survey of Northern Pakistan Volume 1 Languages of Kohistan Volume 2 Languages of Northern Areas Volume 3 Hindko and Gujari Volume 4 Pashto, Waneci, Ormuri Volume 5 Languages of Chitral Series Editor Clare F. O’Leary, Ph.D. Sociolinguistic Survey of Northern Pakistan Volume 1 Languages of Kohistan Calvin R. Rensch Sandra J. Decker Daniel G. Hallberg National Institute of Summer Institute Pakistani Studies of Quaid-i-Azam University Linguistics Copyright © 1992 NIPS and SIL Published by National Institute of Pakistan Studies, Quaid-i-Azam University, Islamabad, Pakistan and Summer Institute of Linguistics, West Eurasia Office Horsleys Green, High Wycombe, BUCKS HP14 3XL United Kingdom First published 1992 Reprinted 2002 ISBN 969-8023-11-9 Price, this volume: Rs.300/- Price, 5-volume set: Rs.1500/- To obtain copies of these volumes within Pakistan, contact: National Institute of Pakistan Studies Quaid-i-Azam University, Islamabad, Pakistan Phone: 92-51-2230791 Fax: 92-51-2230960 To obtain copies of these volumes outside of Pakistan, contact: International Academic Bookstore 7500 West Camp Wisdom Road Dallas, TX 75236, USA Phone: 1-972-708-7404 Fax: 1-972-708-7433 Internet: http://www.sil.org Email: [email protected] REFORMATTING FOR REPRINT BY R. CANDLIN. CONTENTS Preface............................................................................................................viii Maps................................................................................................................. -

Their Uses and Degrees of Risk of Extinc

Saudi Journal of Biological Sciences 28 (2021) 3076–3093 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Saudi Journal of Biological Sciences journal homepage: www.sciencedirect.com Original article Medicinal plants resources of Western Himalayan Palas Valley, Indus Kohistan, Pakistan: Their uses and degrees of risk of extinction ⇑ Mohammad Islam a, , Inamullah a, Israr Ahmad b, Naveed Akhtar c, Jan Alam d, Abdul Razzaq c, Khushi Mohammad a, Tariq Mahmood e, Fahim Ullah Khan e, Wisal Muhammad Khan c, Ishtiaq Ahmad c, ⇑ Irfan Ullah a, Nosheen Shafaqat e, Samina Qamar f, a Department of Genetics, Hazara University, Mansehra 21300, KP, Pakistan b Department of Botany, Women University, AJK, Pakistan c Department of Botany, Islamia College University, 25120 KP, Peshawar, Pakistan d Department of Botany, Hazara University, Mansehra 21300, KP, Pakistan e Department of Agriculture, Hazara University, Mansehra, KP, Pakistan f Department of Zoology, Govt. College University, Faisalabad, Pakistan article info abstract Article history: Present study was intended with the aim to document the pre-existence traditional knowledge and eth- Received 29 December 2020 nomedicinal uses of plant species in the Palas valley. Data were collected during 2015–2016 to explore Revised 10 February 2021 plants resource, their utilization and documentation of the indigenous knowledge. The current study Accepted 14 February 2021 reported a total of 65 medicinal plant species of 57 genera belonging to 40 families. Among 65 species, Available online 22 February 2021 the leading parts were leaves (15) followed by fruits (12), stem (6) and berries (1), medicinally significant while, 13 plant species are medicinally important for rhizome, 4 for root, 4 for seed, 4 for bark and 1 each Keywords: for resin. -

Unit–3 CLIMATE

B.S/B.Ed./MSC Level Geography of Pakistan-I CODE No: 4655 / 8663 / 9351 Department of Pakistan Studies Faculty of Social Sciences & Humanities ALLAMA IQBAL OPEN UNIVERSITY ISLAMABAD i (All rights Reserved with the Publisher) First Printing ................................ 2019 Quantity ....................................... 5000 Printer........................................... Allama Iqbal Open University, Islamabad Publisher ...................................... Allama Iqbal Open University, Islamabad ii COURSE TEAM Chairperson: Prof. Dr. Samina Awan Course Coordinator: Dr. Khalid Mahmood Writers: Mr. Muhammad Javed Mr. Arshad Iqbal Wani Mrs. Zunaira Majeed Mr. Muhammad Haroon Mrs. Iram Zaman Mrs. Seema Saleem Mr. Usman Latif Reviewer: Dr. Khalid Mahmood Editor: Fazal Karim Layout Design: Asrar ul Haque Malik iii FOREWORD Allama Iqbal Open University has the honour to present various programmes from Metric to PhD. level for those who are deprived from regular education due to their compulsions. It is obviously your own institution that provides you the education facility at your door step. Allama Iqbal Open University is the unique in Pakistan which provides education to all citizens; without any discrimination of age, gender, ethnicity, region or religion. It is no doubt that our beloved country had been facing numerous issues since its creation. The initial days were very tough for the newly state but with the blessings of Allah Almighty, it made progress day by day. However, due to conspiracy of external powers and some weaknesses of our leaders, the internal situation of East Pakistan rapidly changed and the end was painful as we lost not only the land but also our Bengali brothers. After the war of 1971, the people and leaders of Pakistan were forced to rethink the future of the remaining country. -

Tree Communities Analysis of Sheikh Buddin National Park, District Dera Ismail Khan, Pakistan

Science, Technology and Development 35 (2): 67-74, 2016 ISSN 0254-6418 / DOI: 10.3923/std.2016.67.74 © 2016 Pakistan Council for Science and Technology Tree Communities Analysis of Sheikh Buddin National Park, District Dera Ismail Khan, Pakistan Attaullah, Nasrullah Khan and Zahid Muhammad Laboratory of Plant Ecology, Department of Botany, University of Malakand, Pakistan Abstract: The present stduy is aimed to study the phytosociological attributes of the Sheikh Buddin National Park, situated in district Dera Ismail Khan. For this study, various field tours were conducted in March, 2013-August, 2015. A total of 26 plant species belonging to 22 generas and 19 families were identified. The data was collected, using quadrate method. The park was divided in 29 stands and 25 quadrates sized (10×10 m) were examined in each stand. Vegetation parameters such as Diameter at Breast Height (DBH), density, frequency and Important Value Index (IVI) of the woody species were recorded. The communities generated on the basis of IVI values resulted in the isolation of seven tree communities. Acacia modesta followed by Olea ferruginea were the dominant communities of the study area. Acacia modesta, Olea ferruginea, Acacia nilotiea, Caperis decidua, Tamarix aphylla, Prosopis cineraria and Ailanthus altissima were common species of the study area, while species such as Acacia nilotica, Tecomella undulate, Ziziphus jujube were randomly distributed. The results revealed that generally the park was dominated by small sized tree species indicating a secondary generation stage and it needs proper management, protection and care. Key words: Tree communities, sheikh buddin national park, Pakistan INTRODUCTION so as not to affect the primary objective of a national park’s establishment (IUCN., 1990). -

421 INDE X a Abakh Hoja Tomb 325 Abbottabad 245-9

© Lonely Planet Publications 421 Index A Saidu Sharif 209-12, 210 Barikot 213 Abakh Hoja Tomb 325 Taxila 88-90, 89 Barpu Glacier 353 Abbottabad 245-9, 246 architecture 53-4 Barsat 284 accommodation 364-6 area codes, see inside front cover Barsin 263 activities 366, see also individual army 34-6 Basant 110 activities arts 52-6, see also individual arts Basha Dam 265 acute mountain sickness (AMS) Artush 330 Basho 286 341, 400 Ashoka, Emperor 237, 249-50 Basho Valley 291-2 Afghan border 154 Ashoka Rocks 249-50 Batagram 256-7 INDEX Afghan refugees 46 Askur Das 306 bathrooms 377-8 Afiyatabad (New Sost) 314-15, 314 Astor Valley 268-70, 269 Batrik 232, 344 AIDS 398 Astor village 268 Battakundi 255 air pollution 70 Athmaqam 185 Batura Glacier 356-7, 7 air travel 382-3 ATMs 373 bazaars 376, 6 airlines 382-3 Avdegar 355-6, 355 Bazira 213 airports 382-3 Avgarch 313-14 begging 50 tickets 383 Awami League 32 Begum Shah Mosque 105 to/from Pakistan 383-5 Ayub National Park 80 Besham 258-9, 258 to/from the KKH 394 Azad Jammu & Kashmir 181-6, 182 Beyal 349 within Pakistan 388-9 earthquake 183 Bhitai, Shah Abdul Latif 52, 176 Akbar 27 Bhong Mosque 126-7 Akbari Mosque 179 B Bhurban 92-3 Alai Valley 259-61, 260 Baba Ghundi Ziarat 316 Bhutto, Benazir 35, 39, 51 alcohol 60 Baba Wali Kandahari 90 Bhutto family 38-9 Alexander the Great 26 Babur 27 Bhutto, Zulfiqar Ali 38, 39 Ali Masjid 200 Babusar Pass 255-6, 267 bicycle travel, see cycling Aliabad 298-9 Badshahi Mosque 103-5 bird-watching 66 All-India Muslim League 29-30 Bagh 186 Birir Valley 233 Allergological -

The Birds of Palas, North-West Frontier Province, Pakistan

FORKTAIL 15 (1999): 77-85 The birds of Palas, North-West Frontier Province, Pakistan N. A. RAJA, P. DAVIDSON, N. BEAN, R. DRIJVERS, D. A. SHOWLER AND C. BARKER The findings of seven ornithological surveys conducted in Palas, District Kohistan, NWFP, Pakistan, between May 1987 and December 1996 are documented. These surveys primarily concentrated on locating pheasants, principally the globally threatened Western Tragopan Tragopan melanocephalus, for which Palas is believed to support the largest single population in the world. A total of 157 species has been recorded in the area, eight of which have restricted-ranges (Stattersfield et al. 1998). An annotated checklist of all these species is presented, together with a summary of status, abundance and breeding biology, if known. Further notes on the omithologically more interesting and significant records are also detailed. LOCATION AND ORNITHOLOGICAL The area spans an altitudinal range of approximately IMPORTANCE 5 km, from the River Indus at 640 m up to the highest peak, Bahader Ser, at 5,151 m, and supports a wide Palas is situated immediately to the east of the River variety of habitats. The topography of Palas is Indus, adjacent to the town of Pattan in District characterized by deep, steep-sided valleys and Kohistan, North-West Frontier Province, between precipitous slopes. The major river traversing the area is 34°52'E to 35°16'E and 72°52'N to 73°35'N (Figure 1), the Musha’ga, which extends from the point where it and covers an area of 1,413 km² (Rafiq 1994). Lying at enters the Indus for about 75 km eastwards to its source. -

Pakistan, 2001

Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized i Environmental Assessment and Review Framework (EARF) for Dasu-Islamabad TL Project TOC TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF ABBREVIATION ........................................................................................................ vii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ...................................................................................................... ES-1 CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION ...............................................................................................1-1 1.1 RATIONALE ..............................................................................................................1-1 1.2 AN OVERVIEW OF THE PROJECT .............................................................................1-1 1.3 NEED FOR PREPARATION OF ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT AND REVIEW FRAMEWORK (EARF) DOCUMENT ...........................................................................1-2 1.4 SCOPE OF SERVICES AND APPROACH TO CARRY OUT THE STUDY ..................1-2 1.4.1 Specific Tasks for the Study Team ....................................................................1-3 1.5 THE STUDY TEAM ......................................................................................................1-4 1.6 STRUCTURE OF THE REPORT ..................................................................................1-5 CHAPTER 2: POLICY, LEGAL AND ADMINISTRATIVE FRAMEWORK ...............................2-1 2.1 GENERAL ..............................................................................................................2-1 -

3 Table of Contents

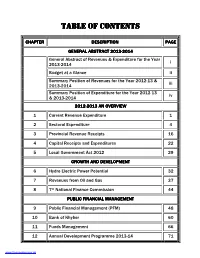

TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER DESCRIPTION PAGE GENERAL ABSTRACT 20132013----20142014 General Abstract of Revenue s & Expenditure for the Year i 2013-2014 Budget at a Glance ii Summary Position of Revenues for the Year 2012 -13 & iii 2013-2014 Summary Position of Expenditure for the Year 2012 -13 iv & 2013-2014 20122012----20132013 AN OVERVIEW 1 Current Revenue Expenditure 1 2 Sectoral Expenditure 4 3 Provincial Revenue Receipts 16 4 Capital Receipts and Expenditures 22 5 Local Government Act 2012 29 GROWTH AND DEVELOPDEVELOPMENTMENT 6 Hydro Electric Power Potential 32 7 Revenues from Oil and Gas 37 8 7th National Finance Commission 44 PUBLIC FINANCIAL MANAGEMENT 9 Public Financial Management (PFM) 48 10 Bank of Khyber 60 11 Funds Management 66 12 Annual Development Programme 2013-14 71 www.financekpp.gov.pk TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS ANNEXURES DESCRIPTION PAGE I CDL Liabilities as on 01-07-2013 109 II Detail of Premature Debt Retirement 110 III Foreign Exchange Loan Liabilities as on 01-07-2013 111 Disbursement of Loans in R/o of Ongoing Foreign IV 113 Projects Share as on 30-06-2013 V General Revenue Receipts 114 VI Current Revenue Expenditure 117 Development Budget by Sector for the Year 2012-13 VII 119 & 2013-14 Annual Development Programme Since 1971-72 on VIII 124 ward Growth in Current Revenue Budget & Revenue IX 125 Receipts Since 1974-75 on ward Grant Wise General Abstract of Current Budget for the X 127 Year 2013-14 www.financekpp.gov.pk FOREWORD White Paper reflects the Provincial Government’s policies and presents an overview of the financial position of the Provincial Government. -

Violence and Belonging

KNUDSEN Honour and violence is a major theme in the anthropology of the Middle East, yet – apart from political violence – most studies approach violence from the perspective of honour. By contrast, this important study examines the meanings of lethal conflict in a little studied tribal society in Pakistan’s unruly North-West Frontier Province (NWFP) and offers a new Violence and perspective on its causes. Based on an in-depth study of local conflicts, the book challenges stereotyped images of a region and people miscast as extremist and militant. VIOLENCEAND BELONGING elonging Being grounded in local ethnography enables the book to shed light B on the complexities of violence, not only at the structural or systemic level, but also as experienced by the men involved in lethal conflict. In this Land, Love way, the book provides a subjective and experiential approach to violence that is applicable beyond the field locality and relevant for advancing the and Lethal Conflict study of violence in the Middle East and South Asia. The book is the first ethnographic study of this region since renowned anthropologist Fredrik in the North-West Barth’s pioneering study in 1954. Frontier Province Are Knudsen is Research Director at the Chr. Michelsen Institute in of Pakistan Bergen, Norway. ‘The material itself is extremely interesting, dealing as it does with an exotic locale, and with an intractable problem of endemic violence. … Dr. Knudsen draws this conflictual situation very well, and adds a great deal to the present-day study of violence, putting what is often seen as primordial in the context of modern conditions.’ – Professor Charles Lindholm, Boston University We should make the best possible use of this analysis: for its daring perspectives, extreme empirical findings, and wide relevance. -

Exploring Patterns of Phytodiversity, Ethnobotany, Plant Geography and Vegetation in the Mountains of Miandam, Swat, Northern Pakistan

EXPLORING PATTERNS OF PHYTODIVERSITY, ETHNOBOTANY, PLANT GEOGRAPHY AND VEGETATION IN THE MOUNTAINS OF MIANDAM, SWAT, NORTHERN PAKISTAN BY Naveed Akhtar M. Phil. Born in Swat, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Academic Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) in the Georg-August-University School of Science (GAUSS) under Faculty of Biology Program Biodiversity and Ecology Georg-August-University of Göttingen Göttingen, 2014 ZENTRUM FÜR BIODIVERSITÄT UND NACHHALTIGE LANDNUTZUNG SEKTION BIODIVERSITÄT, ÖKOLOGIE UND NATURSCHUTZ EXPLORING PATTERNS OF PHYTODIVERSITY, ETHNOBOTANY, PLANT GEOGRAPHY AND VEGETATION IN THE MOUNTAINS OF MIANDAM, SWAT, NORTHERN PAKISTAN Dissertation zur Erlangung des Doktorgrades der Mathematisch-Naturwissenschaftlichen Fakultäten der Georg-August-Universität Göttingen Vorgelegt von M.Phil. Naveed Akhtar aus Swat, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan Göttingen, 2014 WHEN WE ARE FIVE AND THE APPLES ARE FOUR MY MOTHER SAYS “I DO NOT LIKE APPLES” DEDICATED TO My Mother Supervisor: Prof. Dr. Erwin Bergmeier Albrecht-von-Haller-Institute ofPlant Sciences Department of Vegetation & Phytodiversity Analysis Georg-August-University of Göttingen Untere Karspüle 2 37073, Göttingen, Germany Co-supervisor: Prof. Dr. Dirk Hölscher Department of Tropical Silviculture & Forest Ecology Georg-August-University of Göttingen Büsgenweg 1 37077, Göttingen, Germany Table of Contents Acknowledgements ........................................................................................................................................ -

Kp Power Sector Business Plan

KP POWER SECTOR BUSINESS PLAN March 2021 DISCLAIMER This KP Power Sector Business Plan (the “Business Plan”) has been prepared by Adam Smith International and Bridge Factor in association with Axis Law Chambers, TEAM Consultants and Power Planners International on behalf of the SEED Program (Collectively referred as “Consultants”). This business plan is prepared for Pakhtunkhwa Energy Development Organization “PEDO” and Government of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa “GoKP for documenting existing and future power sector plans in the province. This Business Plan has been prepared to assist PEDO and GoKP in making their own evaluation of the existing and future activities within KP Power Sector and does not purport to contain all the information which PEDO and GoKP may desire. In all cases, readers and decision makers should conduct their own due diligence and analysis of the plans and schemes set forth in this Business Plan. The contents of this Business Plan are not to be construed as legal, financial or tax advice. The Consultants do not make any representation or warranty as to the accuracy or completeness of the information contained in this Business Plan and neither shall have any liability for any representations, expressed or implied, contained in, or omitted from, this Business Plan. It is clarified that Consultants did not audit, compile, or apply agreed-upon procedures to any financial information provided by PEDO for this Business Plan. The Consultants, and their affiliated partnerships or bodies corporate, the partners, directors, principals, managers, employees or agents of any of them (the “Parties”) have not independently verified or validated the information and therefore do not make any undertaking, representation or provide any warranty, expressed or implied, as to the accuracy, reasonableness or completeness of the information contained in this Business Plan.