Shanzhai Style in Artistic Practice

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Australia Day and Citizenship Ceremony 2020

MAYOR ROBERT BRIA AUSTRALIA DAY CELEBRATION & CITIZENSHIP CEREMONY 9:30am – 11am Sunday, 26 January 2020 St Peters Street, St Peters RUN ORDER 9.30am Mayor’s Welcome Speech 9.40am Australia Day Awards 9.55am Australia Day Ambassador Speech 10.00am Australian Girl’s Choir 10.10am commence Citizenship Ceremony 10.12am Speeches from MPs 10.20am Oath and Affirmation of Citizenship 10.45am National Anthem 10.50am Closing remarks 1 Good morning and welcome to the City of Norwood Payneham & St Peters Australia Day Celebration and Citizenship Ceremony. My name is Robert Bria. I am the Mayor of the City of Norwood Payneham & St Peters and it is my very great pleasure to welcome you all here this morning to celebrate our national holiday. I would firstly like to acknowledge this land that we meet on today is the traditional land of the Kaurna people and that we respect their spiritual connection with their country. We also acknowledge the Kaurna People as the custodians of the greater Adelaide region and that their cultural and heritage beliefs are still important to the living Kaurna people today. 2 I am delighted to welcome our distinguished guests: Hon Steven Marshall MP, Premier of South Australia. Hon Vickie Chapman MP, Deputy Premier of South Australia Michele Lally, Australia Day Ambassador Michelle from the Australian Electoral Commission Welcome to my fellow Elected Members: Carlo Dottore Kevin Duke Kester Moorhouse Garry Knoblauch John Callisto John Minney Evonne Moore Christel Mex Scott Sims 3 Sue Whitington Fay Patterson, and their partners. A warm welcome also to council staff here this morning, in particular he Council’s Chief Executive Officer, Mr Mario Barone PSM. -

Armen Avanessian Hat Ein Neues Buch. Es Heißt Ethnofuturismen

Jan-Martin Zollitsch 20.9.18 Armen Avanessian / Mahan Moalemi (Hg.), Ethnofuturismen. Aus dem Englischen von Ronald Voullié. Merve Verlag. Leipzig 2018. ETHNO*FUTURISMEN [Armen Avanessian hat ein neues Buch. Es heißt Ethnofuturismen. Er hat es am 13. September im Roten Salon der Volksbühne vorgestellt. (Ich war da.) Der andere Herausgeber des Buches, Mahan Moalemi, war nicht da. Weil er kein Visum bekommen hat, sagt Avanessian. Deswegen hat Avanessian den Vortrag, den Moalemi halten wollte, dann selbst vorgetragen.] Demnach geht es in Ethnofuturismen um die Dimension des »Chronopolitischen«. Diese zeichnet sich aus durch eine Ungleichverteilung der Zukunft. Ethnofuturismen können diesem Ungleichgewicht entgegenwirken. Die (Wieder-)Entdeckung von Zukünften als Ethnofuturismen sei in ihrer ›chronopolitischen‹ Wirkung vergleichbar mit der ulterioren Beförderung eines sich quer durch die »Chronosphäre« fortsetzenden »Butterfly-Effekts«. Ein solcher Effekt sei zu verstehen als eine fortwachsende Abweichung, sich »exponentiell« steigernde »Divergenz«. Auch der lineare Zeitstrahl müsse »sideways« ausgedehnt, in die Räume entlang der »timelines« verzerrt und erweitert werden. Dahinter stünden »Verschiebungen des Zeitbewusstseins«, Mobilitäts- und Vertreibungserfahrungen des ›Globalen Südens‹ und der Versuch in der »Sackgasse« der »identity politics« auszuparken. (Das sind die notierten Stichwörter, aber angereichert; auch denke ich über die Emergenz von Bedeutung nach.) Schon im Juli – im Deutschlandfunk [1] – hatte Avanessian von ›Zeit‹ und ›Zukunft‹ -

With One Voice Community Choir Program

WITH ONE VOICE COMMUNITY CHOIR PROGRAM We hope being part of this choir program will bring you great joy, new connections, friendships, opportunities, new skills and an improved sense of wellbeing and even a job if you need one! You will also feel the creative satisfaction of performing at some wonderful festivals and events. If you have any friends, family or colleagues who would also like to get involved, please give them Creativity Australia’s details, which can be found on the inside of the front cover of this booklet. We hope the choir will grow to be a part of your life for many years. Also, do let us know of any performance or event opportunities for the choir so we can help them come to fruition. We would like to thank all our partners and supporters and ask that you will consider supporting the participation of others in your choir. Published by Creativity Australia. Please give us your email address and we will send you regular choir updates. Prepared by: Shaun Islip – With One Voice Conductor In the meantime, don’t forget to check out our website: www. Kym Dillon – With One Voice Conductor creativityaustralia.org.au Bridget a’Beckett – With One Voice Conductor Andrea Khoza – With One Voice Conductor Thank you for your participation and we are looking forward to a very Marianne Black – With One Voice Conductor exciting and rewarding creative journey together! Tania de Jong – Creativity Australia, Founder & Chair Ewan McEoin – Creativity Australia, General Manager Yours in song, Amy Scott – Creativity Australia, Program Coordinator -

Musik Und Macht

# 2016/07 dschungel https://jungle.world/artikel/2016/07/musik-und-macht Das Konzeptalbum »Brute« der Musikerin Fatima Al Qadiri Musik und Macht Von thomas vorreyer Die aus Kuwait stammende Musikerin und Künstlerin Fatima Al Qadiri lebt mittlerweile in Berlin. Nun legt sie mit »Brute« ein Konzeptalbum über Polizeigewalt und Versammlungsfreiheit vor. New York, Montag, 26. September 2011. Der MSNBC-Moderator Lawrence O’Donnell schaut mit ernster Miene in die Kamera: »Am Wochenende haben ein paar Störenfriede einen friedlichen Protest gegen die Gier der Wall Street in einen Ausbruch des Chaos verwandelt. Sie trugen Pfefferspray, Waffen und Abzeichen.« Die folgenden Bilder zeigen, wie Beamte des NYPD eine kleine Gruppe von Demonstranten in eine Seitenstraße abdrängen und nacheinander zu Boden ringen. Verglichen mit dem, was sich kurze Zeit später in der US-amerikanischen Kleinstadt Ferguson ereignen wird, mögen die Aktionen der Ordnungshüter geradezu harmlos erscheinen – den Eindruck unangemessenen Handelns, von polizeilicher Willkür, bestärken sie dennoch. Mit »Brute« legt die Produzentin Fatima Al Qadiri nun ein Album vor, das Wut und Verzweifelung in den Mittelpunkt stellt. »Wut treibt dich hinaus auf die Straße, Verzweiflung bringt dich wieder hinein«, erklärt sie. Die Stimmung der Bewohner der westlichen Welt will sie mit ihrem Werk eingefangen haben. Sound-Samples wie jenes von Lawrence O’Donnell sind die akustischen Eckpfeiler. Doch die Perspektive der Kuwaiterin Al Qadiri ist vor allem die einer desillusionierten Außenseiterin. Zum Gespräch bittet sie kurzfristig in ein Café in Berlin-Mitte. Draußen Baustellenlärm, drinnen Al Qadiri unter Strom. Sie wohnt ums Eck. Bis morgen will sie eine kurzfristig angenommene Auftragsarbeit fertigstellen. Dennoch nimmt sie sich mehr als eine Stunde Zeit. -

AUSTRALIAN BUSH SONGS Newport Convention Bush Band Songbook

AUSTRALIAN BUSH SONGS Newport Convention Bush Band Songbook Friday, 11 July 2003 Song 1 All for Me GrOG...........................................................................................................................................................................2 SONG 2 Billy of tea.................................................................................................................................................................................. 3 Song 3 BLACK VELVET BAND............................................................................................................................................................ 4 Song 4 BOTANTY BAY.......................................................................................................................................................................... 5 Song 5 Click Go the Shears.......................................................................................................................................................................7 Song 6 Dennis O'Reilly............................................................................................................................................................................. 8 Song 7 Drovers Dream..............................................................................................................................................................................9 Song 8 Dying Stockman..........................................................................................................................................................................10 -

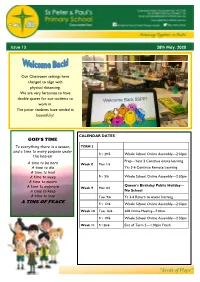

Newsletter 13. 28-05-2020.Pub

Issue 13 28th May, 2020 Our Classroom settings have changed to align with physical distancing. We are very fortunate to have double spaces for our students to work in. The junior students have settled in beautifully! CALENDAR DATES GOD’S TIME To everything there is a season, TERM 2 and a time to every purpose under Fri 29/5 Whole School Online Assembly—2:30pm the heaven: Prep—Year 2 Continue onsite learning A time to be born Week 8 Mon 1/6 A time to die Yrs 3-6 Continue Remote Learning A time to heal A time to weep Fri 5/6 Whole School Online Assembly—2:30pm A time to mourn Queen’s Birthday Public Holiday— A time to embrace Week 9 Mon 8/6 A time to keep No School A time to love Tues 9/6 Yr 3-6 Return to onsite learning A TIME OF PEACE Fri 12/6 Whole School Online Assembly—2:30pm Week 10 Tues 16/6 SAB Online Meeting—7:00am Fri 19/6 Whole School Online Assembly—2:30pm Week 11 Fri 26/6 End of Term 2—1:00pm Finish “Seeds of Hope” PRINCIPAL’S MESSAGE Dear Families, Seeds of Hope Welcome back to the beautiful smiling faces of our Preps, Year 1s and Year 2s. We have missed you terribly and we are so glad you have returned. Congratulations to you all for being so independent and managing all your bags and belongings all by yourselves. We are so very proud of you all! Our transition back to onsite learning has been exceptionally smooth and the children have been fantastic in adjusting to the changes that have taken place; coming in to school, in their classrooms, in the playground and around the buildings. -

December 2006

December 2006 Issue 3 ISSN 1553-3069 Table of Contents Editorial Continued Growth: Further Expansion for Integral Review .... 1 Jonathan Reams Short Works Toward Integral Dialog: Provisional Guidelines for Online Forums ...... 4 Tom Murray and Sara Ross Tomorrow’s Sunrise – A Plea for the Future You, Me and We ............ 14 Barbara Nussbaum Four Days in France: An Integral Interlude ........................................... 16 Tam Lundy Rationale for an Integral Theory of Everything ..................................... 20 Ervin Laszlo Book Review Clearings in the Forest: On the Study of Leadership ....... 23 Jonathan Reams The Map, the Gap, and the Territory ..................................................... 25 Bonnitta Roy cont'd next page ISSN 1553-3069 The Dance Integral ................................................................................. 29 Andrew Campbell Articles Essay (with abstract in English) Drei Avantgarde-Strömungen des heutigen US-Geisteslebens – und ihre Beziehung zu Europa ................ 39 Roland Benedikter Of Syntheses and Surprises: Toward a Critical Integral Theory ........... 62 Daniel Gustav Anderson Measuring an Approximate g in Animals and People ........................... 82 Michael Lamport Commons The Centrality of Human Development in International Development Programs: An Interview with Courtney Nelson................................... 100 Russ Volckmann A Process Model of Integral Theory .................................................... 118 Bonnitta Roy ISSN 1553-3069 Editorial Continued Growth: Further Expansion for Integral Review Welcome to the third issue of Integral Review. With this issue, we accomplish our goal of producing issues on a semiannual basis, and continue to expand the community of authors, reviewers and readers of IR. With the publication of this issue, we also announce some exciting new additions to IR that we believe will support this community even further. First, we are pleased to announce the formation of the Integral Review Editorial Advisory Board. -

Migration of Mexicans to Australia

Migration of Mexicans to Australia MONICA LAURA VAZQUEZ MAGGIO Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Social Sciences, University of New South Wales September 2013 Acknowledgements I would like to express my profound gratitude to a number of people who provided me with invaluable support throughout this entire PhD journey. I have been privileged to have two marvellous and supportive PhD supervisors. I am immensely grateful to my Social Sciences supervisor, Dr. Alan Morris, who guided me with his constant encouragement, valuable advice and enormous generosity. As a fresh new PhD student, full of excitement on my first days after I arrived in Australia, I remember encountering a recently graduated PhD student who, after I told her that my supervisor was Alan Morris, assured me I was in good hands. At that time, I had no idea of the magnitude of what she meant. Alan has truly gone above and beyond the role of a supervisor to guide me so brilliantly through this doctorate. He gracefully accepted the challenge of leading me in an entirely new discipline, as well as through the very challenging process of writing in a second language. Despite his vast commitments and enormous workload, Alan read my various manuscripts many times. I am also deeply thankful to my Economics supervisor, Dr. Peter Kriesler, for whom without his warm welcome, I would have not come to this country. I am extremely indebted to Peter for having put his trust in me before arriving in Australia and for giving me the opportunity to be part of this University. -

Copyrighted Material

Index 3rd Plenary of the 17th Party Congress All-China Federation of Industry and 147, 163 Commerce (ACFIC) 256, 257, 258 3rd Plenary Session of the 11th CPC [or All-China Youth Federation 58, 444, 460 Party] National Congress xvi, 53, 62, 263 America 5, 6, 9, 12, 16, 17, 25, 32, 33, 38, 4th National Conference of the 70, 75, 102, 106, 136, 138–139, 140, 141, Representatives of Literary and Art 157, 162, 190, 194, 202, 235, 237, 241, Workers 336 243, 254, 261, 270, 279, 288, 290, 297, 9th National People’s Congress 102, 105 310, 326, 336, 352, 354, 357, 365, 377, 11th Five-Year Plan 146, 157, 230 379, 380, 382–389, 391, 407, 413, 416, 14th Party Congress (14th National Party 426, 446, 464, 469, 494, 498, 503, 509, Congress) 80, 84, 97 510, 514, 515, 516, 517 15th Party Congress (15th National Party American media xviii, 32, 313, 315, 319, Congress) 95, 96, 97, 98 331, 407 16th Party Congress (16th National Party Anhui 54, 254, 312, 424, 426 Congress) 114, 119 Anshan 214 17th Party Congress (17th National Party Anti-Japanese War 39, 40, 54, 352, 354 Congress) xiv, xvi, 19, 131, 163, 179, 188, Anti-Rightist Campaign 42, 437, 501 333, 493. APEC (Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation) 30th anniversary (of reform and opening-up) 139, 223, 378 ix, xv, xvii, 143 artists 238, 316, 333, 336, 338, 342, 345, 60 Minutes 412, 415, 445 346, 355, 356, 484, 500 60th anniversary of the People’s Republic of Asian Financial Crisis 91, 185, 265 China xiii, xvi, 40, 532 Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) 80th anniversary (CPC) 109, 112 139, 223, 378 863 -

Fatima Al Qadiri

FATIMA AL QADIRI: CHINAS OF THE MIND Elena Harvey Collins, independent curator | September 25, 2015 — January 10, 2016 Fatima Al Qadiri’s music articulates the disconnect upon historical sites and museums in Iraq and Syria. The between what is experienced and what is imagined, how fact that many works of art, such as the Assyrian statuary places are distorted and romanticized in our collective recently attacked in Mosul, Iraq, are in fact plaster replicas memory, and how they can endure as a feeling or a mood. of originals held in European museums adds to the layers Pulling from multiple cultural references, Al Qadiri builds of confusion and to the sense of things not being where sonic architectures that spatialize both past and future. A they belong, or where we left them. However, there is a particular hook pulls me into her music: the icy, skittering plastic quality to the melodies of Al Qadiri’s album, a sounds of Grime, a genre of music originating in London distancing that comes from the way that the artist’s raw during the early 2000s. Grime was a very specific sound memories are overlaid with removed experience, including that could only have sprung from London’s hybridized, sounds sampled from the video game Desert Strike: Return bustling, DIY music scene, coming by way of jungle, UK to the Gulf, based on the US military’s response to Iraq’s Garage, 2-Step, dancehall, and rap. It was music made 1991 invasion of Kuwait. Al Qadiri evokes the strangeness by teenage musicians on computers in housing estate and alienation of re-experiencing a war as entertainment, bedrooms, music for dancefloors, characterized by a conveying a sense of cultural slippage—how sounds, moody scene and raves that got shut down early by the places, and events are mediated by distance, politics, and police. -

Manifesto Per Una Politica Accelerazionista P. 20

P. 4 – MANIFESTO PER UNA POLITICA ACCELERAZIONISTA P. 20 – INVENTING THE FUTURE - CONCLUSIONS Alex Williams e Nick Srnicek P. 32 – RED STACK ATTACK! ALGORITMI, CAPITALE E AUTOMAZIONE DEL COMUNE Tiziana Terranova P. 46 – ABNORMAL ENCEPHALIZATION IN THE AGE OF MACHINE LEARNING Matteo Pasquinelli P. 62 – APPUNTI PER UNA DISCOGRAFIA ACCELERAZIONISTA October 2016 Valerio Mattioli L’invito a partecipare a DAMA ci ha posti di fronte alla Published by necessità di sviluppare un dispositivo che approfondisse un KABUL magazine preciso argomento, quello dell’Accelerazionismo e dei suoi www.kabulmagazine.com sviluppi teorici ed estetici, al di là del testo scritto. Per questo Edition of 25 motivo, la raccolta di testi qui presentata e una serie di video Turin, November 2016 proiettati sabato 5 novembre a Palazzo Saluzzo di Paesana Design and print by riusciranno forse, se non certamente a esaurire la notevole Fabrizio Cosenza portata dell’argomento, quantomeno a documentare parte delle maggiori riflessioni scaturite negli ultimi anni del dibattito Texts by Alex Williams e Nick Srnicek contemporaneo. Tiziana Terranova Teorizzato nel 2013 da Nick Srnicek e Alex Williams, Matteo Pasquinelli l’Accelerazionismo è stato immediatamente accolto dal Valerio Mattioli sentire comune non solo per le idee esposte nel suo Manifesto, ma soprattutto per la riconsiderazione del futuro, messo da parte negli ultimi da una spinta di diffusa Retromania. Criticando l’atteggiamento intellettuale di passiva analisi critica dell’accademismo odierno, tale pensiero ha spinto all’esigenza di ripensare, con una prospettiva rivolta al nuovo, alla possibilità di cambiare ciò che Adam Curtis ha chiamato hyper normalization. Ancor prima di parlare di tecnologia, l’Accelerazionismo apre gli occhi sull’attività che scandisce e definisce la nostra quotidianità: il lavoro. -

Bringing Down the System One Song at a Time

Bringing down the System one song at a time Music | Bittles’ Magazine: The music column from the end of the world: March New Album Reviews. After the colossal disappointment of Anti, together with the bloated arrogance of Life Of Pablo you could be forgiven for coming to the conclusion that these are dark times for music. I mean, Ed Sheeran’s X has just spent over 80 consecutive weeks in the official charts for fucks sake! And there does seem to be a dearth of great albums in the charts right now. Adele, Justin Bieber, Ronan Keating or Little Mix are hardly names to get your aural sense tingling with delight. By JOHN BITTLES Yet, as always, there are still a few musical nuggets to be found. For instance, this week we review an electric riposte to modern society by Fatima Al Qadiri, Prins Thomas‘ kosmische meanderings, the rock dynamism of Heron Oblivion, Andrew Weatherall’s cocky swagger, the trip hop flavoured jazz of Submotion Orchestra, and lots more. So, pop on your spectacles, open your ears, and let us begin… This month we’ll start with Fatima Al Qadiri’s second album Brute. While last year’s Asiatisch was inspired largely by ideas of a future China, for her sophomore LP the artist explores »the theme of authority, the relationship between police, citizens and protest worldwide, particularly of her adopted home in the United States«. The result is a deeply immersive electronic odyssey which, thankfully, is filled with as many moments of glacial beauty as righteous rage. Containing sampled dialogue from urban protests, Brute is a chilling portrayal of a modern society which has sleepwalked into a police state.