Fatima Al Qadiri

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

EDM (Dance Music): Disco, Techno, House, Raves… ANTHRO 106 2018

EDM (Dance Music): Disco, Techno, House, Raves… ANTHRO 106 2018 Rebellion, genre, drugs, freedom, unity, sex, technology, place, community …………………. Disco • Disco marked the dawn of dance-based popular music. • Growing out of the increasingly groove-oriented sound of early '70s and funk, disco emphasized the beat above anything else, even the singer and the song. • Disco was named after discotheques, clubs that played nothing but music for dancing. • Most of the discotheques were gay clubs in New York • The seventies witnessed the flowering of gay clubbing, especially in New York. For the gay community in this decade, clubbing became 'a religion, a release, a way of life'. The camp, glam impulses behind the upsurge in gay clubbing influenced the image of disco in the mid-Seventies so much that it was often perceived as the preserve of three constituencies - blacks, gays and working-class women - all of whom were even less well represented in the upper echelons of rock criticism than they were in society at large. • Before the word disco existed, the phrase discotheque records was used to denote music played in New York private rent or after hours parties like the Loft and Better Days. The records played there were a mixture of funk, soul and European imports. These "proto disco" records are the same kind of records that were played by Kool Herc on the early hip hop scene. - STARS and CLUBS • Larry Levan was the first DJ-star and stands at the crossroads of disco, house and garage. He was the legendary DJ who for more than 10 years held court at the New York night club Paradise Garage. -

Traditional Funk: an Ethnographic, Historical, and Practical Study of Funk Music in Dayton, Ohio

University of Dayton eCommons Honors Theses University Honors Program 4-26-2020 Traditional Funk: An Ethnographic, Historical, and Practical Study of Funk Music in Dayton, Ohio Caleb G. Vanden Eynden University of Dayton Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.udayton.edu/uhp_theses eCommons Citation Vanden Eynden, Caleb G., "Traditional Funk: An Ethnographic, Historical, and Practical Study of Funk Music in Dayton, Ohio" (2020). Honors Theses. 289. https://ecommons.udayton.edu/uhp_theses/289 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the University Honors Program at eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Traditional Funk: An Ethnographic, Historical, and Practical Study of Funk Music in Dayton, Ohio Honors Thesis Caleb G. Vanden Eynden Department: Music Advisor: Samuel N. Dorf, Ph.D. April 2020 Traditional Funk: An Ethnographic, Historical, and Practical Study of Funk Music in Dayton, Ohio Honors Thesis Caleb G. Vanden Eynden Department: Music Advisor: Samuel N. Dorf, Ph.D. April 2020 Abstract Recognized nationally as the funk capital of the world, Dayton, Ohio takes credit for birthing important funk groups (i.e. Ohio Players, Zapp, Heatwave, and Lakeside) during the 1970s and 80s. Through a combination of ethnographic and archival research, this paper offers a pedagogical approach to Dayton funk, rooted in the styles and works of the city’s funk legacy. Drawing from fieldwork with Dayton funk musicians completed over the summer of 2019 and pedagogical theories of including black music in the school curriculum, this paper presents a pedagogical model for funk instruction that introduces the ingredients of funk (instrumentation, form, groove, and vocals) in order to enable secondary school music programs to create their own funk rooted in local history. -

Garage House Music Whats up with That

Garage House Music whats up with that Future funk is a sample-based advancement of Nu-disco which formed out of the Vaporwave scene and genre in the early 2010s. It tends to be more energetic than vaporwave, including elements of French Home, Synth Funk, and making use of Vaporwave modifying techniques. A style coming from the mid- 2010s, often explained as a blend of UK garage and deep home with other elements and strategies from EDM, popularized in late 2014 into 2015, typically mixes deep/metallic/sax hooks with heavy drops somewhat like the ones discovered in future garage. One of the very first house categories with origins embeded in New York and New Jersey. It was named after the Paradise Garage bar in New york city that operated from 1977 to 1987 under the prominent resident DJ Larry Levan. Garage house established along with Chicago home and the outcome was home music sharing its resemblances, affecting each other. One contrast from Chicago house was that the vocals in garage house drew stronger impacts from gospel. Noteworthy examples consist of Adeva and Tony Humphries. Kristine W is an example of a musician involved with garage house outside the genre's origin of birth. Also understood as G-house, it includes very little 808 and 909 drum machine-driven tracks and often sexually explicit lyrics. See likewise: ghettotech, juke house, footwork. It integrates components of Chicago's ghetto house with electro, Detroit techno, Miami bass and UK garage. It includes four-on-the-floor rhythms and is normally faster than a lot of other dance music categories, at approximately 145 to 160 BPM. -

Download Press

LA PINCE RECORDS RELEASES ARTISTS PUBLIC RELATIONS CONTACT # PRESS KIT PRESS L A PINCE RECORDS THE GENESIS HOUSE OF THE CREW TECHNO reated in 2016 by the collective dj’s03 DUB CREATORS (DJD2B, Steve Ko & Lucho Misterhands), La Pince Records stand out by Creleasing its records in vinyl & digital. Rocked since the 90’s by the sounds of Detroit & Berlin, has bring to the collective on subtle blend to them music. Definitely dedicated to the dance floor, all tracks can be classified in the Techno / House categories. EP RELEASE VINYLS P LA PINCE RECORDS / PRESS KIT / 03 RELEASES LPR001 DJ D2B - MONGOLISTIC EP irst EP, DJ D2B deliver to you 3 unique & exclusive directed pieces House/Techno influenced by the minimal trends. FAlong with deep beats05 & shaman inspiration vocals, hypnotic melodies with sensual tones, “Which promise you a nice trip into the clouds”. A1 - MONGOLISTIC (Original Mix) A2 - SENSUAL EMOTION (Original Mix) B1 - FLOAT IN THE CLOUD (Original Mix) Released on: June 2016. AVAILABLE ON CLICK HERE TO LISTEN Syncrophone Records shop, Techno Import, House Monkey Records. decks.de, deejay.de, juno.co.uk, hhv.de, technique.co.jp, redeyerecords. co.uk. Beatport, JunoDownload, TrackSource, Apple Music, Spotifiy, Youtube P RELEASES / PRESS KIT / 05 LPR002 DUB CREATORS - KANPEKINA EP or the LPR002 DUB CREATORS release on their own imprint La Pince Records. This trio deliver to us their KANPEKINA EP. 06FMade up with 4 strong-deep bassline tracks the original mix & 3 dance-floor remix witch goes from House to Tech-House. A1 - KANPEKINA (Original Mix) A2 - KANPEKINA (Lucho Misterhands Remix) B1 - KANPEKINA (DJ D2B Remix) B2 - KANPEKINA (Steve Ko Remix) Supported by DJ Handmade (Tresor Berlin) . -

Discourse on Disco

Chapter 1: Introduction to the cultural context of electronic dance music The rhythmic structures of dance music arise primarily from the genre’s focus on moving dancers, but they reveal other influences as well. The poumtchak pattern has strong associations with both disco music and various genres of electronic dance music, and these associations affect the pattern’s presence in popular music in general. Its status and musical role there has varied according to the reputation of these genres. In the following introduction I will not present a complete history of related contributors, places, or events but rather examine those developments that shaped prevailing opinions and fields of tension within electronic dance music culture in particular. This culture in turn affects the choices that must be made in dance music production, for example involving the poumtchak pattern. My historical overview extends from the 1970s to the 1990s and covers predominantly the disco era, the Chicago house scene, the acid house/rave era, and the post-rave club-oriented house scene in England.5 The disco era of the 1970s DISCOURSE ON DISCO The image of John Travolta in his disco suit from the 1977 motion picture Saturday Night Fever has become an icon of the disco era and its popularity. Like Blackboard Jungle and Rock Around the Clock two decades earlier, this movie was an important vehicle for the distribution of a new dance music culture to America and the entire Western world, and the impact of its construction of disco was gigantic.6 It became a model for local disco cultures around the world and comprised the core of a common understanding of disco in mainstream popular music culture. -

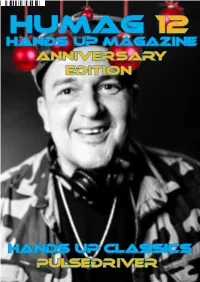

Hands up Classics Pulsedriver Hands up Magazine Anniversary Edition

HUMAG 12 Hands up Magazine anniversary Edition hANDS Up cLASSICS Pulsedriver Page 1 Welcome, The time has finally come, the 12th edition of the magazine has appeared, it took a long time and a lot has happened, but it is done. There are again specials, including an article about pulsedriver, three pages on which you can read everything that has changed at HUMAG over time and how the de- sign has changed, one page about one of the biggest hands up fans, namely Gabriel Chai from Singapo- re, who also works as a DJ, an exclusive interview with Nick Unique and at the locations an article about Der Gelber Elefant discotheque in Mühlheim an der Ruhr. For the first time, this magazine is also available for download in English from our website for our friends from Poland and Singapore and from many other countries. We keep our fingers crossed Richard Gollnik that the events will continue in 2021 and hopefully [email protected] the Easter Rave and the TechnoBase birthday will take place. Since I was really getting started again professionally and was also ill, there were unfortu- nately long delays in the publication of the magazi- ne. I apologize for this. I wish you happy reading, Have a nice Christmas and a happy new year. Your Richard Gollnik Something Christmas by Marious The new Song Christmas Time by Mariousis now available on all download portals Page 2 content Crossword puzzle What is hands up? A crossword puzzle about the An explanation from Hands hands up scene with the chan- Up. -

Armen Avanessian Hat Ein Neues Buch. Es Heißt Ethnofuturismen

Jan-Martin Zollitsch 20.9.18 Armen Avanessian / Mahan Moalemi (Hg.), Ethnofuturismen. Aus dem Englischen von Ronald Voullié. Merve Verlag. Leipzig 2018. ETHNO*FUTURISMEN [Armen Avanessian hat ein neues Buch. Es heißt Ethnofuturismen. Er hat es am 13. September im Roten Salon der Volksbühne vorgestellt. (Ich war da.) Der andere Herausgeber des Buches, Mahan Moalemi, war nicht da. Weil er kein Visum bekommen hat, sagt Avanessian. Deswegen hat Avanessian den Vortrag, den Moalemi halten wollte, dann selbst vorgetragen.] Demnach geht es in Ethnofuturismen um die Dimension des »Chronopolitischen«. Diese zeichnet sich aus durch eine Ungleichverteilung der Zukunft. Ethnofuturismen können diesem Ungleichgewicht entgegenwirken. Die (Wieder-)Entdeckung von Zukünften als Ethnofuturismen sei in ihrer ›chronopolitischen‹ Wirkung vergleichbar mit der ulterioren Beförderung eines sich quer durch die »Chronosphäre« fortsetzenden »Butterfly-Effekts«. Ein solcher Effekt sei zu verstehen als eine fortwachsende Abweichung, sich »exponentiell« steigernde »Divergenz«. Auch der lineare Zeitstrahl müsse »sideways« ausgedehnt, in die Räume entlang der »timelines« verzerrt und erweitert werden. Dahinter stünden »Verschiebungen des Zeitbewusstseins«, Mobilitäts- und Vertreibungserfahrungen des ›Globalen Südens‹ und der Versuch in der »Sackgasse« der »identity politics« auszuparken. (Das sind die notierten Stichwörter, aber angereichert; auch denke ich über die Emergenz von Bedeutung nach.) Schon im Juli – im Deutschlandfunk [1] – hatte Avanessian von ›Zeit‹ und ›Zukunft‹ -

Musik Und Macht

# 2016/07 dschungel https://jungle.world/artikel/2016/07/musik-und-macht Das Konzeptalbum »Brute« der Musikerin Fatima Al Qadiri Musik und Macht Von thomas vorreyer Die aus Kuwait stammende Musikerin und Künstlerin Fatima Al Qadiri lebt mittlerweile in Berlin. Nun legt sie mit »Brute« ein Konzeptalbum über Polizeigewalt und Versammlungsfreiheit vor. New York, Montag, 26. September 2011. Der MSNBC-Moderator Lawrence O’Donnell schaut mit ernster Miene in die Kamera: »Am Wochenende haben ein paar Störenfriede einen friedlichen Protest gegen die Gier der Wall Street in einen Ausbruch des Chaos verwandelt. Sie trugen Pfefferspray, Waffen und Abzeichen.« Die folgenden Bilder zeigen, wie Beamte des NYPD eine kleine Gruppe von Demonstranten in eine Seitenstraße abdrängen und nacheinander zu Boden ringen. Verglichen mit dem, was sich kurze Zeit später in der US-amerikanischen Kleinstadt Ferguson ereignen wird, mögen die Aktionen der Ordnungshüter geradezu harmlos erscheinen – den Eindruck unangemessenen Handelns, von polizeilicher Willkür, bestärken sie dennoch. Mit »Brute« legt die Produzentin Fatima Al Qadiri nun ein Album vor, das Wut und Verzweifelung in den Mittelpunkt stellt. »Wut treibt dich hinaus auf die Straße, Verzweiflung bringt dich wieder hinein«, erklärt sie. Die Stimmung der Bewohner der westlichen Welt will sie mit ihrem Werk eingefangen haben. Sound-Samples wie jenes von Lawrence O’Donnell sind die akustischen Eckpfeiler. Doch die Perspektive der Kuwaiterin Al Qadiri ist vor allem die einer desillusionierten Außenseiterin. Zum Gespräch bittet sie kurzfristig in ein Café in Berlin-Mitte. Draußen Baustellenlärm, drinnen Al Qadiri unter Strom. Sie wohnt ums Eck. Bis morgen will sie eine kurzfristig angenommene Auftragsarbeit fertigstellen. Dennoch nimmt sie sich mehr als eine Stunde Zeit. -

Performance in EDM - a Study and Analysis of Djing and Live Performance Artists

California State University, Monterey Bay Digital Commons @ CSUMB Capstone Projects and Master's Theses Capstone Projects and Master's Theses 12-2018 Performance in EDM - A Study and Analysis of DJing and Live Performance Artists Jose Alejandro Magana California State University, Monterey Bay Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.csumb.edu/caps_thes_all Part of the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation Magana, Jose Alejandro, "Performance in EDM - A Study and Analysis of DJing and Live Performance Artists" (2018). Capstone Projects and Master's Theses. 364. https://digitalcommons.csumb.edu/caps_thes_all/364 This Capstone Project (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by the Capstone Projects and Master's Theses at Digital Commons @ CSUMB. It has been accepted for inclusion in Capstone Projects and Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ CSUMB. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Magaña 1 Jose Alejandro Magaña Senior Capstone Professor Sammons Performance in EDM - A Study and Analysis of DJing and Live Performance Artists 1. Introduction Electronic Dance Music (EDM) culture today is often times associated with top mainstream DJs and producers such as Deadmau5, Daft Punk, Calvin Harris, and David Guetta. These are artists who have established their career around DJing and/or producing electronic music albums or remixes and have gone on to headline world-renowned music festivals such as Ultra Music Festival, Electric Daisy Carnival, and Coachella. The problem is that the term “DJ” can be mistakenly used interchangeably between someone who mixes between pre-recorded pieces of music at a venue with a set of turntables and a mixer and an artist who manipulates or creates music or audio live using a combination of computers, hardware, and/or controllers. -

S New Albums Reviewed

A Different Kind Of Racket: June/July’s New Albums Reviewed Music | Bittles’ Magazine: The music column from the end of the world I was watching Wimbledon the other day when I came to the startling realisation that tennis is boring. Hoping that all it might need was a good soundtrack, I reduced the volume on the telly, replacing it with the morose musings of Darklands by The Jesus And Mary Chain. Much Better! Experiencing yet another epiphany I turned the TV off altogether, allowing the Reid brothers the attention they fully deserve. By JOHN BITTLES The following albums may not reach the hallowed heights of The JAMC, but they will entertain you a lot more than a couple of posh boys hitting a ball really hard ever could. So, get yourself some Pimms, a bowl of strawberries and cream, and let us begin. To prove my point we’ll start with the rich, woozy pop experiments of Helsinki-based singer/producer Jaakko Eino Kalevi and his rather wonderful self-titled debut LP. Taking the fuggy haze of modern psychedelia and injecting it with a generous helping of pop hooks and a sensuous sense of groove helps create one of the outstanding albums of the summer. Laid-back, dreamy and always charming, the record’s ten tracks touch on funk, electronica, chill-wave, indie, rock and more. Deeper Shadows contains a loose bassline to die for, Jek is a slow, languid jam, while Don’t Ask Me Why should be in the dictionary under the definition of cool. With Jaakko’s treated falsetto quite low in the mix, the record hits the listener like an aural wave, seducing them quietly but surely until all resistance is swept away. -

December 2006

December 2006 Issue 3 ISSN 1553-3069 Table of Contents Editorial Continued Growth: Further Expansion for Integral Review .... 1 Jonathan Reams Short Works Toward Integral Dialog: Provisional Guidelines for Online Forums ...... 4 Tom Murray and Sara Ross Tomorrow’s Sunrise – A Plea for the Future You, Me and We ............ 14 Barbara Nussbaum Four Days in France: An Integral Interlude ........................................... 16 Tam Lundy Rationale for an Integral Theory of Everything ..................................... 20 Ervin Laszlo Book Review Clearings in the Forest: On the Study of Leadership ....... 23 Jonathan Reams The Map, the Gap, and the Territory ..................................................... 25 Bonnitta Roy cont'd next page ISSN 1553-3069 The Dance Integral ................................................................................. 29 Andrew Campbell Articles Essay (with abstract in English) Drei Avantgarde-Strömungen des heutigen US-Geisteslebens – und ihre Beziehung zu Europa ................ 39 Roland Benedikter Of Syntheses and Surprises: Toward a Critical Integral Theory ........... 62 Daniel Gustav Anderson Measuring an Approximate g in Animals and People ........................... 82 Michael Lamport Commons The Centrality of Human Development in International Development Programs: An Interview with Courtney Nelson................................... 100 Russ Volckmann A Process Model of Integral Theory .................................................... 118 Bonnitta Roy ISSN 1553-3069 Editorial Continued Growth: Further Expansion for Integral Review Welcome to the third issue of Integral Review. With this issue, we accomplish our goal of producing issues on a semiannual basis, and continue to expand the community of authors, reviewers and readers of IR. With the publication of this issue, we also announce some exciting new additions to IR that we believe will support this community even further. First, we are pleased to announce the formation of the Integral Review Editorial Advisory Board. -

Beatport Launches New Melodic House & Techno Genre Category

BEATPORT LAUNCHES NEW MELODIC HOUSE & TECHNO GENRE CATEGORY BERLIN, DE - MARCH 20, 2018 - Reflecting one of the dominant sounds on global dancefloors, BEATPORT, a division of LiveStyle, today announced the addition of its new Melodic House & Techno genre. In 2018, Beatport's House and Techno charts are swelling with a style frequently heard in the sets of scene-leading DJs like Dixon, Tale Of Us and Solomun. It's a heady, melodic, arpeggiator-heavy sound that's both brooding and built for clubs. With artists including Stephan Bodzin, Patrice Bäumel, Oliver Koletzki, Mind Against, Matador, Finnebassen and Bedouin leading the charge, this strain of house and techno is thriving on labels like Afterlife, Diynamic, Innervisions and Stil Vor Talent. Previously, this content has been dispersed amongst Beatport's Techno, Deep House, Tech House and Electronica genres, making it increasingly difficult to know where to find the most up-to-date releases in this style. Our dedicated team will now curate the best Melodic House & Techno tracks each week in one place, with regularly rotating content from the labels and artists at the forefront of the melodic takeover. "While Beatport's main House and Techno categories represent the biggest floor-filling tracks across the genres, Melodic House & Techno brings together a thriving sound that has not been easy to categorise as the lines blur between sounds and styles,” commented Beatport Label & Artist Relations Director, Jack Bridges. "Combining genres in this way under a new specialised category follows the successful launch of Leftfield House & Techno on the store in 2017, which caters for the underground DJ while recognising that blurring of genre lines.