PROJECT PERFORMANCE ASSESSMENT Kingdom of Lesotho

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lesotho Vulnerability Assessment Committee

2016 Lesotho Government Lesotho VAC Table of Contents List of Tables ................................LESOTHO................................................................ VULNERABILITY.............................................................................. 0 List of Maps ................................................................................................................................................................................ 0 Acknowledgments ................................ASSESSMENT................................................................ COMMITTEE................................................................ ... 3 Key Findings .............................................................................................................................................................................. 4 Executive Summary ................................................................................................................................................................ 5 INTERVENTION MODALITY SELECTION Section 1: Objectives, methodology and limitations ................................................................................................. 7 1.1 Objectives ................................In light ................................of the findings................................ from the LVAC................................ Market Assessment................................ that assessed....... 9 the functionality and performance of Lesotho’s food markets, LVAC proceeded to 1.2 Methodology -

Social Fences M ... Sotho and Eastern Cape.Pdf

Extensive livestock production remains a significant part of livelihoods in many parts of southern Africa where land is not held in freehold, including Lesotho and the former 'homeland' of Transkei, now part of the Eastern Cape province of South Africa. In such areas, sustainable livestock production requires some form of community based range management. Based on field research and project support work in the Maluti District of the former Transkei and the Mohale's Hoek and Quthing Districts of southern Lesotho, this paper explores the contrasting views of community based range management that prevail in the two countries. It aims to reveal the social and economic tensions that exist between social fencing approaches and metal fencing approaches, and to highlight the different perceptions of governance and institutional roles that result from the two countries' political experiences over the 20* century. This comparative discussion should yield policy lessons for both countries, and the wider region. The Drakensberg escarpment separates two very different experiences of governance and resource management in these two areas. In southern Lesotho, chiefs continue to play a strong role in local government and natural resource management. Cattle, sheep and goats still play an important role in local livelihoods. Livestock are herded by boys and young men. Grazing areas, demarcated by natural features or beacons, are unfenced. They are opened and closed by the chiefs sitting in council with senior men of the community, who also punish infringements of local range management rules. Like their Xhosa-speaking neighbours in the former Transkei homeland area of the Eastern Cape, Basotho have suffered heavily from stock theft over the past decade. -

Information Sheet on Ramsar Wetlands (RIS) Categories Approved by Recommendation 4.7, As Amended by Resolution VIII.13 of the Conference of the Contracting Parties

Information Sheet on Ramsar Wetlands (RIS) Categories approved by Recommendation 4.7, as amended by Resolution VIII.13 of the Conference of the Contracting Parties. Note for compilers: 1. The RIS should be completed in accordance with the attached Explanatory Notes and Guidelines for completing the Information Sheet on Ramsar Wetlands. Compilers are strongly advised to read this guidance before filling in the RIS. 2. Once completed, the RIS (and accompanying map(s)) should be submitted to the Ramsar Bureau. Compilers are strongly urged to provide an electronic (MS Word) copy of the RIS and, where possible, digital copies of maps. 1. Name and address of the compiler of this form: FOR OFFICE USE ONLY. DD MM YY Ms Limpho Motanya, Department of Water Affairs. Ministry of Natural Resources, P O Box 772, Maseru, LESOTHO. Designation date Site Reference Number 2. Date this sheet was completed/updated: October 2003 3. Country: LESOTHO 4. Name of the Ramsar site: Lets`eng - la – Letsie 5. Map of site included: Refer to Annex III of the Explanatory Note and Guidelines, for detailed guidance on provision of suitable maps. a) hard copy (required for inclusion of site in the Ramsar List): yes (X) -or- no b) digital (electronic) format (optional): yes (X) -or- no 6. Geographical coordinates (latitude/longitude): The area lies between 30º 17´ 02´´ S and 30º 21´ 53´´ S; 28º 08´ 53´´ E and 28º 15´ 30´´ E xx 7. General location: Include in which part of the country and which large administrative region(s), and the location of the nearest large town. -

Smuggling Anti-Apartheid Refugees in Rural Lesotho in the 1960S and 1970S

Smuggling Anti-Apartheid Refugees in Rural Lesotho in the 1960s and 1970s EIGHT HOMEMAKERS, COMMUNISTS AND REFUGEES: SMUGGLING ANTI-APARTHEID REFUGEES IN RURAL LESOTHO IN THE 1960s AND 1970si John Aerni-Flessner Michigan State University Abstract This article tells the story of Maleseka Kena, a woman born in South Africa but who lived most of her adult life in rural Lesotho. It narrates how her story of helping apartheid refugees cross the border and move onward complicates understandings of what the international border, belonging, and citizenship meant for individuals living near it. By interweaving her story with larger narratives about the changing political, social, and economic climate of the southern African region, it also highlights the spaces that women had for making an impact politically despite facing structural obstacles both in the regional economy and in the villages where they were living. This article relies heavily on the oral testimony of Maleseka herself as told to the author, but also makes use of press sources from Lesotho, and archival material from the United States and the United Kingdom. Keywords: Lesotho, Refugees, Apartheid, Gender, Borderlands Maleseka Kena lives in the small village of Tsoelike, Auplas, a mountain community of no more than four-hundred people in the Qacha’s Nek District deep in the southern mountains of Lesotho.ii When I first met her, 76-year old ‘Me Kena was wearing a pink bathrobe over her clothes on a cool fall morning, cooking a pot of moroho, the spinach dish that is a staple of Basotho cooking.iii I had come to Auplas on the encouragement of a friend who had tipped me © Wagadu 2015 ISSN: 1545-6196 184 Wagadu Volume 13 Summer 2015 off that her husband, Jacob Kena, an influential member of the Communist Party of Lesotho, would make a great interview for my research on independence-era Lesotho. -

Restricted Not for Publication Oversea,$ Geoi

/ /. .. I / • RESTRICTED NOT FOR PUBLICATION OVERSEA,$ GEOI.DGICAL SURVEYS M I N E R A L R E S 0 U R C E S p I VIS I 0 N SOURCES OF INFORMATION (SERIES B: REFERENCES) PRELIMINARY NOTE N0.43 "Annotated Bibliography on the Geology-, Mineral and Water Resources o~ Basutoland (Revised)" Reference · M 6562/96 October. 1963 64-78 GRAY'S INN ROAD . I.DNDON, w.c.1. Tel.ephone: CHAncery 4531 OVERSEAS GEOLOGICAL SURVEYS MINERAL RESOURCES DIVISION ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY ON THE GEOLOGY, MINERAL AND WATER RESOURCES OF BASUTOLA.i'fD, (REVISED) Draft - October 1963 M<t References .W..rd'rked (a) are available in OGS Reference Library, those marked {c) have been consulted in other libraries. Important references have been marked with an asterisk. REFERENCES (BY AUTHOR) (a) l. ANON. 1952. "An Economic Survey of the Colonial Territories, 1951; Volume I, The Central Af'rican and High Commission Territories, Northern Rhodesia, Nyasaland, Basutoland, Bechuanaland and Swaziland." Colon.No. 281(1), 105 pp., tables, maps. (London: H.M. Stationery Office.) [Bauutoland (pp. 65-74): l{inerals (p. 70) "A geologi cal Survey carried out in 1938-39 failed to reveal minerals of any value to the Territory. Coal is found in thin seams in the Mohales Hoek district but does not occur 1n paying quantities." DSP.] (a} 2. ANON. 1955. "Colonial Reports, Annual Report on Basutoland for the .year 1954." 96 pp., refs., map. (London: H.M. Stationery Office.) · [Soil conservation (pp. 37-38) Peasant agricultural practice has included monoculture, with little return of animal manure to the soil and overstocking of grazing areas which have resulted in large areas i becoming infertile and eroded. -

The World Bank for Official Use Only

Document of The World Bank For Official Use Only Public Disclosure Authorized Report No: 75232-LS PROJECT APPRAISAL DOCUMENT ON A PROPOSED CREDIT FROM THE INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT ASSOCIATION IN THE AMOUNT OF SDR 7.8 MILLION (US$12 MILLION EQUIVALENT) Public Disclosure Authorized AND PROPOSED GRANT IN THE AMOUNT OF US$4 MILLION FROM THE HEALTH RESULTS INNOVATION TRUST FUND TO THE KINGDOM OF LESOTHO FOR A Public Disclosure Authorized MATERNAL AND NEWBORN HEALTH PERFORMANCE-BASED FINANCING PROJECT March 15, 2013 Health, Nutrition and Population, Eastern and Southern Africa Country Department AFCS1 Africa Region Public Disclosure Authorized This document is being made publicly available prior to Board consideration. This does not imply a presumed outcome. This document may be updated following Board consideration and the updated document will be made publicly available in accordance with the Bank’s policy on Access to Information. CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (Exchange Rate Effective January 31, 2013) Currency Unit = LSL LSL 8.97 = US$ 1 US$ 1.5413403 = SDR 1 FISCAL YEAR April 1 – March 31 ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS ADF Africa Development Fund AFTME Africa Region Financial Management - East unit AFTHE Africa Health, Nutrition & Population East/South unit AFTSG Africa Region Safeguards Group AIDS Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome AJR Annual Joint Review ANC Antenatal Care ARV Antiretroviral Drugs BCG Bacillus Calmette Guerin BOS Bureau of Statistics CAS Country Assistance Strategy CBA Cost Benefit Analysis CBO Community-Based Organization CHAL -

Internal Ex-Post Evaluation for Grant Aid Project Conducted By

) Internal Ex-Post Evaluation for Grant Aid Project Conducted by South Africa Office: December, 2014 Country Name Project for Constriction of Secondary Schools in the Kingdom of Lesotho Kingdom of Lesotho I. Project Outline Secondary education in Lesotho was a five-year educational course for students aged 13 to 18 years who have completed primary education. As of 2005, the net enrollment ratios (NER) in secondary education remained low at 25.4%. While the introduction of Free Primary Education (FPE) in 2000 raised NER in primary education to 83.2%. In this circumstance, it was expected that NER in the secondary education would be increased, and accordingly the demands for development of school Background infrastructures for secondary education would be significantly increased. In this respect, the Ministry of Education and Training estimated the shortage of 3,622 class rooms in 2015, and put a priority on the improvement of accessibility to the secondary education service by constructing new school facilities equipped with dormitories, kitchens and canteens combined with multi-purpose halls in the remote areas and highly populated areas. To improve the accessibility of secondary education service by constructing school facilities for Objectives of the secondary education and procuring school furniture in seven project sites/districts*. Project *The target seven district: Leribe, Maseru, Berea, Quthing, Butha-Buthe, Mokhotlong, Mafeteng 1. Project sites: Hlotse (Leribe district), Maseru (Maseru district), Teyateyaneng (Berea district), -

Notes and References

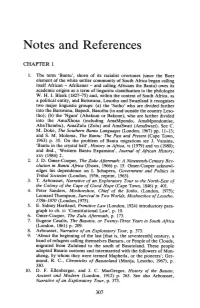

Notes and References CHAPTER 1 1. The term 'Bantu', shorn of its racialist overtones (since the Boer element of the white settler community of South Africa began calling itself African- Afrikaner- and calling Africans the Bantu) owes its academic origins as a term of linguistic classification to the philologist W. H. I. Bleek (1827-75) and, within the context of South Africa, as a political entity, and Botswana, Lesotho and Swaziland it recognises two major linguistic groups: (a) the 'Sotho' who are divided further into the Batswana, Bapedi, Basotho (in and outside the country Leso tho); (b) the 'Nguni' (Abakuni or Bakone), who are further divided into the AmaXhosa (including AmaMpondo, AmaMpondomise, AbaThembu), AmaZulu (Zulu) and AmaSwati (AmaSwazi). See C. M. Doke, The Southern Bantu Languages (London, 1967) pp. 11-13; and S. M. Molema, The Bantu: The Past and Present (Cape Town, 1963) p. 35. On the problem of Bantu migrations see J. Vansina, 'Bantu in the crystal ball', History in Africa, VI (1979) and VII (1980); and ibid., 'Western Bantu Expansion', Journal of African History, XXV (1984) 2. 2. J.D. Omer-Cooper, The Zulu Aftermath: A Nineteenth-Century Rev olution in Bantu Africa (Essex, 1966) p. 15. Omer-Cooper acknowl edges his dependence on I. Schapera, Government and Politics in Tribal Societies (London, 1956, reprint, 1963). 3. T. Arbousset, Narrative of an Exploratory Tour to the North-East of the Colony of the Cape of Good Hope (Cape Town, 1846) p. 401. 4. Peter Sanders, Moshoeshoe, Chief of the Sotho, (London, 1975); Leonard Thompson, Survival in Two Worlds, Moshoeshoe of Lesotho, 178(r..J870 (London,1975). -

Cross-Border Raiding and Community Conflict in the Lesotho-South African Border Zone

THE SOUTHERN AFRICAN MIGRATION PROJECT CROSS-BORDER RAIDING AND COMMUNITY CONFLICT IN THE LESOTHO-SOUTH AFRICAN BORDER ZONE MIGRATION POLICY SERIES NO. 21 CROSS-BORDER RAIDING AND COMMUNITY CONFLICT IN THE LESOTHO-SOUTH AFRICAN BORDER ZONE GARY KYNOCH AND THERESA ULICKI WITH TSEPANG CEKWANE, BOOI MOHAPI, MAMPOLOKENG MOHAPI, NTSOAKI PHAKISI AND PALESA SEITHLEKO Published by Idasa, 6 Spin Street, Church Square, Cape Town, 8001, and Queen’s University, Canada. Copyright Southern African Migration Project (SAMP) 2001 ISBN 1-919798-16-1 First published 2001 Design by Bronwen Dachs Müller Typeset in Goudy All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without prior permission from the publishers. Bound and printed by Logo Print Print consultants Mega Digital, Cape Town CROSS-BORDER RAIDING AND COMMUNITY CONFLICT IN THE LESOTHO-SOUTH AFRICAN BORDER ZONE GARY KYNOCH AND THERESA ULICKI WITH TSEPANG CEKWANE, BOOI MOHAPI, MAMPOLOKENG MOHAPI, NTSOAKI PHAKISI AND PALESA SEITHLEKO SERIES EDITOR: JONATHAN CRUSH SOUTHERN AFRICAN MIGRATION PROJECT 2001 CONTENTS PAGE EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1 INTRODUCTION 5 RESEARCH METHODOLOGY 6 THE DIMENSIONS OF STOCK THEFT 7 CAUSES OF STOCK THEFT 11 THE ECONOMIC IMPACTS OF STOCK RAIDING 12 THE SOCIAL IMPACTS OF RAIDING 16 THE DECLINE OF CROSS-BORDER CO-OPERATION 21 POLICING THE CRISIS 25 THE POLITICS OF STOCK THEFT 30 CONCLUSION AND POLICY RECOMMENDATIONS 33 APPENDIX 36 ENDNOTES 39 MIGRATION POLICY SERIES 44 MIGRATION POLICY SERIES NO. 21 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ovement backwards and forwards across borders for work is often considered to be the primary form of unauthorized movement in Southern Africa. -

The Basuto Rebellion, Civil War and Reconstruction, 1880-1884

University of Nebraska at Omaha DigitalCommons@UNO Student Work 7-1-1973 The Basuto rebellion, civil war and reconstruction, 1880-1884 Douglas Gene Kagan University of Nebraska at Omaha Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/studentwork Recommended Citation Kagan, Douglas Gene, "The Basuto rebellion, civil war and reconstruction, 1880-1884" (1973). Student Work. 441. https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/studentwork/441 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Student Work by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE BA5UT0 REBELLION, CIVIL WAR, AND RECONSTRUCTION, 1B8O-1804 A Thesis Presented to the Dapartment of History and the Faculty of the Graduate College ‘University of Nebraska at Omaha In Partial Fulfillment if the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts by Douglas Gene Kagan July 1973 UMI Number: EP73079 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI EP73079 Published by ProQuest LLC (2015). Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 t Accepted for the faculty of The Graduate College of the University of Nebraska at Omaha, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Art3. -

Lebohang Nts'inyi

LEGAL NOTICE NO. 81 OF 2006 Proclamation of Monuments, Relics, Fa una and Flora (Amend ment) Notice, 2006 Pursuant to section 8 of the Historical, Monuments, Relics, Fauna and Bora Act 19671, I, LEBO HANG NTS'INYI Minister of Tourism, Environment and Culture amend the Proclamation of Monuments, Relics, Fauna and B ora, 19692 by inserting the following ; (a) Under protected Monuments _ 10. Botha-Bothe Plateau (Borha-Bothe District) 11. Sekubu Cave (Borha-Bothe District) 12. Liphofung Cultural and Heritage site (Botha-Bothe District) 13. Khalo-la-Lithunya (Borha-Bothe District) 14. Menkhoaneng Cultural Heritage Site (Botha-Bothe District) 15. Matita grave ((Berea District) 16. Ha Kome cave dwellings (Berea District) 17. Malimong Heritage Site (Berea District) 18. Khalo-la-Lithethana (Berea District) 19. Bokhopa Peak (Berea District) 20. St.Saviours Church Mission (ACL) (Leribe District) 21. Litemekoaneng (Leribe District) 22. Fika-le-Mohala (Maseru District) 23. Makoanyane Square (Old Post Office) (Maseru District) 24. 'Maletsunyane Falls (Maseru District) 25. All old churches/all Gov. buildings [I 00yrs old] (Maseru District) 26. Old graves of national heroes (Maseru District) 27. Mafeteng cemetery /Lichaba graveyard (Mafeteng District) 28. Qalabane Mountain (Mafeteng District) 29. Lets' a-la-luma (Mafeteng District) 30. Lets' a-la-Letsie (Quthing District) 31. Old bridge (Alwyn's Kop)(Quthing District) 32. Khubelu Hot SpringslMineral (Mokhotlong District) 33. Molumong Church Mission (LEC) (Mokhotlong District) 34. Thaban a-Ntlenyana (Mokhotlong District) 35. Mount-aux-Sources/ Senqu source (wetland)(Mokhotlong District) 36. Tsoelike Mission/suspended bridge (Qacha 's Nek District) 37. Siloe Mission (LEC) (Mohale's Hoek District) - (b) Under Protected Flora 14.Boophane disticha (Leshoma) IS. -

Community and Household Surveillance (Chs) Findings

Disaster Management Authority World Food Programme COMMUNITY AND HOUSEHOLD SURVEILLANCE (CHS) FINDINGS October/November 2008 (Round 11) Community & Household Surveillance Round Eight Findings Draft Report January, 2009 Acknowledgements The Disaster Management Authority (DMA) and WFP wishes to thank the households interviewed for their invaluable time and contribution, without which the Community and Household Surveillance would not have been possible. DMA and WFP also wish to acknowledge the significant contribution that the Disaster Management District Taskforce (DDMTs) made to the enumeration of this round of CHS. All the DDMTs that released staff to participate in the CHS exercise as follows: 1. Malisemelo Tsekoa-DMA Berea 16. Ntsepiseng Seeqela-DMA Mohale's Hoek 2. Josephina Ramasala-DMA Berea 17. Matokelo Chaka-DMA Mohale's Hoek 3. Mojabeng Tsepe-FNCO Berea 18. Maphakisi Sekese-DMA Mohale's Hoek 4. Malitlhaku Lipholo-DMA Butha-Buthe 19. Disebo Sutha-DMA Mokhotlong 5. Beketsane Ntsebeng-DMA Butha-Buthe 20. Ntsiuoa Sello-DMA Mokhotlong 6. Maphomolo Tsekoa-FNCO Butha Buthe 21. Maleshoane Nkhabu-DMA Mokhotlong 7. Maboitelo Maputla-DMA Leribe 22. Mathabo Mohlekoa-DMA Qachas' Nek 8. Roma Neko-DMA Leribe 23. Moliehi Mabula-DMA Qachas' Nek 9. Mammopa Likotsi-FNCO Leribe 24. Puseletso Tlali-DMA Qachas' Nek 10. Lefulesele Mojakisane-DMA Mafeteng 25. Mamoipone Letsie-DMA Quthing 11. Halimmoho Pitikoe-DMA Mafeteng 26. Thato Mahasela-DMA Quthing 12. Nteboheleng Mothae-FNCO Mafeteng 27. Maneo Motanya-FNCO Quthing 13. Sello Phate-DMA Maseru 28. Mako Rametse-DMA Thaba-Tseka 14. Mamoorosi Sekhonyana-FNCO Maseru 29. Nonkosi Tshabalala-DMA Thaba-Tseka 15. Mathabang Kalaka-DMA Maseru 30. Tsoana M Pebane-DMA Thaba-Tseka DMA also expresses gratitude to WFP Johannesburg Regional Bureau for funding this round of CHS, and also to Eric Kenefick-WFP Regional VAM and M&E advisor who provided technical assistance of data and reporting.