Jaghori and Malistan Districts, Ghazni Province

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fråga-Svar Afghanistan. Resväg Mellan Kabul Och Ghazni

2015-09-03 Fråga-svar Afghanistan. Resväg mellan Kabul och Ghazni Fråga - Går det flyg mellan Kabul och Ghazni? - Är resvägen mellan Kabul och Ghazni säker för hazarer? - Finns det några organisationer i landet som kan bistå andra med t.ex. eskort för att göra resan säker? - Hur kan underåriga ta sig fram? Svar Nedan följer en sammanställning av information från olika källor. Sammanställningen gör inte anspråk på att vara uttömmande. Refererade dokument bör alltid läsas i sitt sammanhang. Vad gäller säkra resvägar så kan läget snabbt förändras. Vad som gällde då nedanstående dokument skrevs gäller kanske inte idag! Austalia Refugee Review Tribunal (May 2015): Domen handlar om en hazar från Ghazni som under lång tid levt som flykting i Iran. Underlaget till beslutet beskriver situationen angående resvägar i Afghanistan speciellt i provinsen Ghazni. Se utdrag nedan: 33. DFAT’s 2014 Report statcontains the following in relation to road security in Afghanistan: Insecurity compounds the poor condition of Afghanistan’s limited road network, particularly those roads that pass through areas contested by insurgents. Taliban and criminal elements target the national highway and secondary roads, setting up arbitrary armed checkpoints. Sida 1 av 8 Official ANP and ANA checkpoints designed to secure the road are sometimes operated by poorly-trained officers known to use violence to extort bribes. More broadly, criminals and insurgents on roads target all ethnic groups, sometimes including kidnapping for ransom. It is often difficult to separate criminality (such as extortion) from insurgent activity. Individuals working for, supporting or associated with the Government and the international community are at high risk of violence perpetrated by insurgents on roads in Afghanistan. -

Afghanistan State Structure and Security Forces

European Asylum Support Office Afghanistan State Structure and Security Forces Country of Origin Information Report August 2020 SUPPORT IS OUR MISSION European Asylum Support Office Afghanistan State Structure and Security Forces Country of Origin Information Report August 2020 More information on the European Union is available on the Internet (http://europa.eu). ISBN: 978-92-9485-650-0 doi: 10.2847/115002 BZ-02-20-565-EN-N © European Asylum Support Office (EASO) 2020 Reproduction is authorised, provided the source is acknowledged, unless otherwise stated. For third-party materials reproduced in this publication, reference is made to the copyrights statements of the respective third parties. Cover photo: © Al Jazeera English, Helmand, Afghanistan 3 November 2012, url CC BY-SA 2.0 Taliban On the Doorstep: Afghan soldiers from 215 Corps take aim at Taliban insurgents. 4 — AFGHANISTAN: STATE STRUCTURE AND SECURITY FORCES - EASO COUNTRY OF ORIGIN INFORMATION REPORT Acknowledgements This report was drafted by the European Asylum Support Office COI Sector. The following national asylum and migration department contributed by reviewing this report: The Netherlands, Office for Country Information and Language Analysis, Ministry of Justice It must be noted that the review carried out by the mentioned departments, experts or organisations contributes to the overall quality of the report, it but does not necessarily imply their formal endorsement of the final report, which is the full responsibility of EASO. AFGHANISTAN: STATE STRUCTURE AND SECURITY -

The Kingdom of Afghanistan: a Historical Sketch George Passman Tate

University of Nebraska Omaha DigitalCommons@UNO Books in English Digitized Books 1-1-1911 The kingdom of Afghanistan: a historical sketch George Passman Tate Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/afghanuno Part of the History Commons, and the International and Area Studies Commons Recommended Citation Tate, George Passman The kingdom of Afghanistan: a historical sketch, with an introductory note by Sir Henry Mortimer Durand. Bombay: "Times of India" Offices, 1911. 224 p., maps This Monograph is brought to you for free and open access by the Digitized Books at DigitalCommons@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Books in English by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Tate, G,P. The kfn&ean sf Af&mistan, DATE DUE I Mil 7 (7'8 DEDICATED, BY PERMISSION, HIS EXCELLENCY BARON HARDINGE OF PENSHURST. VICEROY AND GOVERNOR-GENERAL OF INDIA, .a- . (/. BY m HIS OBEDIENT, SERVANT THE AUTHOR. il.IEmtev 01 the Asiniic Society, Be?zg-nl, S?~rueyof I~din. dafhor of 'I Seisinqz : A Menzoir on the FJisio~y,Topo~rcrphj~, A7zliquiiies, (112d Peo$Ie of the Cozi?zt~y''; The F/.o?zlic7,.~ of Baluchisia'nn : Travels on ihe Border.? of Pe~szk n?zd Akhnnistnn " ; " ICalnf : A lMe??zoir on t7ze Cozl7~try and Fnrrzily of the Ahntadsai Khn7zs of Iinlnt" ; 4 ec. \ViTkI AN INrPR<dl>kJCTOl2Y NO'FE PRINTED BY BENNETT COLEMAN & Co., Xc. PUBLISHED AT THE " TIMES OF INDIA" OFFTCES, BOMBAY & C.1LCUTT-4, LONDON AGENCY : gg, SI-IOE LANE, E.C. -

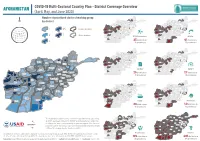

AFGHANISTAN COVID-19 Multi-Sectoral Country Plan - District Coverage Overview (April, May, and June 2020) Number of Prioritized Clusters/Working Group

AFGHANISTAN COVID-19 Multi-Sectoral Country Plan - District Coverage Overview (April, May, and June 2020) Number of prioritized clusters/working group Badakhshan Badakhshan Jawzjan Kunduz Jawzjan Kunduz Balkh Balkh N by district Takhar Takhar Faryab Faryab Samangan Samangan Sar-e-Pul Baghlan Sar-e-Pul Baghlan Panjsher Nuristan Panjsher Nuristan Badghis Parwan Badghis Parwan Bamyan Kapisa Kunar Bamyan Kapisa Kunar Laghman Laghman Kabul Kabul Maidan Wardak Maidan Wardak Ghor Nangarhar Ghor Nangarhar 1 4-5 province boundary Logar Logar Hirat Daykundi Hirat Daykundi Paktya Paktya Ghazni Khost Ghazni Khost Uruzgan Uruzgan Farah Farah Paktika Paktika 2 7 district boundary Zabul Zabul DTM Prioritized: WASH: Hilmand Hilmand Kandahar Kandahar Nimroz Nimroz 25 districts in 41 districts in 3 10 provinces 13 provinces Badakhshan Badakhshan Jawzjan Kunduz Jawzjan Kunduz Balkh Balkh Takhar Takhar Faryab Faryab Samangan Samangan Sar-e-Pul Baghlan Sar-e-Pul Baghlan Panjsher Nuristan Panjsher Nuristan Badghis Parwan Badghis Parwan Bamyan Kapisa Kunar Bamyan Kapisa Kunar Laghman Laghman Kabul Kabul Maidan Wardak Maidan Wardak Badakhshan Ghor Nangarhar Ghor Nangarhar Jawzjan Logar Logar Kunduz Hirat Daykundi Hirat Daykundi Balkh Paktya Paktya Takhar Ghazni Khost Ghazni Khost Uruzgan Uruzgan Farah Farah Paktika Paktika Faryab Zabul Zabul Samangan Baghlan Hilmand EiEWG: Hilmand ESNFI: Sar-e-Pul Kandahar Kandahar Nimroz Nimroz Panjsher Nuristan 25 districts in 27 districts in Badghis Parwan Bamyan Kapisa Kunar 10 provinces 12 provinces Laghman Kabul Maidan -

Watershed Atlas Part IV

PART IV 99 DESCRIPTION PART IV OF WATERSHEDS I. MAP AND STATISTICS BY WATERSHED II. AMU DARYA RIVER BASIN III. NORTHERN RIVER BASIN IV. HARIROD-MURGHAB RIVER BASIN V. HILMAND RIVER BASIN VI. KABUL (INDUS) RIVER BASIN VII. NON-DRAINAGE AREAS PICTURE 84 Aerial view of Panjshir Valley in Spring 2003. Parwan, 25 March 2003 100 I. MAP AND STATISTICS BY WATERSHED Part IV of the Watershed Atlas describes the 41 watersheds Graphs 21-32 illustrate the main characteristics on area, popu- defined in Afghanistan, which includes five non-drainage areas lation and landcover of each watershed. Graph 21 shows that (Map 10 and 11). For each watershed, statistics on landcover the Upper Hilmand is the largest watershed in Afghanistan, are presented. These statistics were calculated based on the covering 46,882 sq. km, while the smallest watershed is the FAO 1990/93 landcover maps (Shapefiles), using Arc-View 3.2 Dasht-i Nawur, which covers 1,618 sq. km. Graph 22 shows that software. Graphs on monthly average river discharge curve the largest number of settlements is found in the Upper (long-term average and 1978) are also presented. The data Hilmand watershed. However, Graph 23 shows that the largest source for the hydrological graph is the Hydrological Year Books number of people is found in the Kabul, Sardih wa Ghazni, of the Government of Afghanistan – Ministry of Irrigation, Ghorband wa Panjshir (Shomali plain) and Balkhab watersheds. Water Resources and Environment (MIWRE). The data have Graph 24 shows that the highest population density by far is in been entered by Asian Development Bank and kindly made Kabul watershed, with 276 inhabitants/sq. -

Balkh's Chamtal District Cleaned up from Rebels

www.outlookafghanistan.net www.thedailyafghanistan.com facebook.com/The.Daily.Outlook.Afghanistan facebook.com/The.Daily.Afghanistan Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Phone: 0093 (799) 005019/777-005019 Phone: 0093 (799) 005019/777-005019 Add: Sarai Ghazni, District 3, Kabul Add: Sarai Ghazni, District 3, Kabul Back Page August 22, 2017 Jalalabad Clear Ghazni Kandahar Clear Clear Mazar Clear Herat Clear Bamayan Clear Kabul Clear Daily Outlook 36°C 32°C 38°C 37°C 33°C 26°C 31°C Weather 28°C 16°C 24°C 25°C 16°C 12°C 18°C Forcast Balkh’s Chamtal District Cleaned up from Rebels MAZAR-I-SHARIF - Local officials on Monday said Chamtal district of Security Forces northern Balkh province has been cleaned of militants during an Af- Recapture Some Areas ghan forces operation. An operation launched by the Shahin of Mirzawlang Military Corps against militants was SAR-I-PUL CITY - Security forces have underway since Saturday night and taken control of Sheram and Kalta Taw ar- was ended late on Sunday. eas of Mirzawlang village in northern Sar- Amanullah Mobin, the commander i-Pul province, an official said on Monday. for the corps, told reporters that Governor Mohammad Zahir Wahdat told around 50 militants suffered casual- Pajhwok Afghan News the security forces ties and eight others were arrested carried out a predawn operation for retak- during the operation. Six security ing the valley. The security personnel suf- personnel were also killed. fered no casualties. He said that there were no rebels cur- Mirzawlang was overrun by militants on rently in Chamtal district after the August 4 when 50 civilians were reported- operation. -

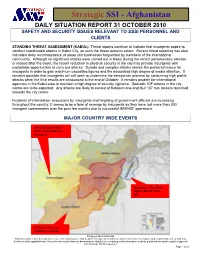

Daily Situation Report 31 October 2010 Safety and Security Issues Relevant to Sssi Personnel and Clients

Strategic SSI - Afghanistan DAILY SITUATION REPORT 31 OCTOBER 2010 SAFETY AND SECURITY ISSUES RELEVANT TO SSSI PERSONNEL AND CLIENTS STANDING THREAT ASSESSMENT (KABUL): Threat reports continue to indicate that insurgents aspire to conduct coordinated attacks in Kabul City, as such the threat remains extant. Recent threat reporting has also indicated likely reconnaissance of areas and businesses frequented by members of the international community. Although no significant attacks were carried out in Kabul during the recent parliamentary election, or indeed after the event, the recent reduction in physical security in the city may provide insurgents with exploitable opportunities to carry out attacks. Suicide and complex attacks remain the preferred choice for insurgents in order to gain maximum casualties figures and the associated high degree of media attention. It remains possible that insurgents will still seek to undermine the democratic process by conducting high profile attacks when the final results are announced at the end of October. It remains prudent for international agencies in the Kabul area to maintain a high degree of security vigilance. Sporadic IDF attacks in the city centre are to be expected. Any attacks are likely to consist of between one and four 107 mm rockets launched towards the city centre. Incidents of intimidation, executions by insurgents and targeting of government officials are increasing throughout the country. It seems to be a form of revenge by insurgents as they have lost more than 300 insurgent commanders over the past few months due to successful IM/ANSF operations. MAJOR COUNTRY WIDE EVENTS Herat: Influencial local Tribal Leader killed by insurgents Nangarhar: Five attacks against Border Police OPs Helmand: Five local residents murdered Privileged and Confidential This information is intended only for the use of the individual or entity to which it is addressed and may contain information that is privileged, confidential, and exempt from disclosure under applicable law. -

Hazara Tribe Next Slide Click Dark Blue Boxes to Advance to the Respective Tribe Or Clan

Program for Culture & Conflict Studies www.nps.edu/programs/ccs Advance to Hazara Tribe next slide Click dark blue boxes to advance to the respective tribe or clan. Hazara Abak / Abaka Besud / Behsud / Basuti Allakah Bolgor Allaudin Bubak Bacha Shadi Chagai Baighazi Chahar Dasta / Urni Baiya / Baiyah Chula Kur Barat Dahla / Dai La Barbari Dai Barka Begal Dai Chopo Beguji / Bai Guji Dai Dehqo / Dehqan Reference: Courage Services Inc., Tribal Hierarchy & Dictionary of Afghanistan: A Reference Aid for Analysts, (February 2007). Adamec. Vol 6; Hazaras Poladi, 37; EE Bacon, P.20-31 Topography, Ethnology, Resources & History of Afghanistan. Part II. Calcutta:, 1871 (p. 628). Program for Culture & Conflict Studies www.nps.edu/programs/ccs Return to Advance to First slide Hazara Tribe next slide Hazara Dai Kundi / Deh Kundi Dayah Dai Mardah / Dahmarda Dayu Dai Mirak Deh Zengi Dai Mirkasha Di Meri / Dai Meri Dai Qozi Di Mirlas / Dai Mirlas Dai Zangi / Deh Zangi Di Nuri / Dai Nuri Daltamur Dinyari /Dinyar Damarda Dosti Darghun Faoladi Dastam Gadi / Gadai Reference: Courage Services Inc., Tribal Hierarchy & Dictionary of Afghanistan: A Reference Aid for Analysts, (February 2007). Adamec. Vol 6; Hazaras Poladi, 37; EE Bacon, P.20-31 Topography, Ethnology, Resources & History of Afghanistan. Part II. Calcutta:, 1871 (p. 628). Program for Culture & Conflict Studies www.nps.edu/programs/ccs Return to Advance to First slide Hazara Tribe next slide Hazara Gangsu Jaokar Garhi Kadelan Gavi / Gawi Kaghai Ghaznichi Kala Gudar Kala Nao Habash Kalak Hasht Khwaja Kalanzai Ihsanbaka Kalta Jaghatu Kamarda Jaghuri / Jaghori Kara Mali Reference: Courage Services Inc., Tribal Hierarchy & Dictionary of Afghanistan: A Reference Aid for Analysts, (February 2007). -

19 October 2020 "Generated on Refers to the Date on Which the User Accessed the List and Not the Last Date of Substantive Update to the List

Res. 1988 (2011) List The List established and maintained pursuant to Security Council res. 1988 (2011) Generated on: 19 October 2020 "Generated on refers to the date on which the user accessed the list and not the last date of substantive update to the list. Information on the substantive list updates are provided on the Council / Committee’s website." Composition of the List The list consists of the two sections specified below: A. Individuals B. Entities and other groups Information about de-listing may be found at: https://www.un.org/securitycouncil/ombudsperson (for res. 1267) https://www.un.org/securitycouncil/sanctions/delisting (for other Committees) https://www.un.org/securitycouncil/content/2231/list (for res. 2231) A. Individuals TAi.155 Name: 1: ABDUL AZIZ 2: ABBASIN 3: na 4: na ﻋﺒﺪ اﻟﻌﺰﻳﺰ ﻋﺒﺎﺳﯿﻦ :(Name (original script Title: na Designation: na DOB: 1969 POB: Sheykhan Village, Pirkowti Area, Orgun District, Paktika Province, Afghanistan Good quality a.k.a.: Abdul Aziz Mahsud Low quality a.k.a.: na Nationality: na Passport no: na National identification no: na Address: na Listed on: 4 Oct. 2011 (amended on 22 Apr. 2013) Other information: Key commander in the Haqqani Network (TAe.012) under Sirajuddin Jallaloudine Haqqani (TAi.144). Taliban Shadow Governor for Orgun District, Paktika Province as of early 2010. Operated a training camp for non- Afghan fighters in Paktika Province. Has been involved in the transport of weapons to Afghanistan. INTERPOL- UN Security Council Special Notice web link: https://www.interpol.int/en/How-we-work/Notices/View-UN-Notices- Individuals click here TAi.121 Name: 1: AZIZIRAHMAN 2: ABDUL AHAD 3: na 4: na ﻋﺰﯾﺰ اﻟﺮﺣﻤﺎن ﻋﺒﺪ اﻻﺣﺪ :(Name (original script Title: Mr Designation: Third Secretary, Taliban Embassy, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates DOB: 1972 POB: Shega District, Kandahar Province, Afghanistan Good quality a.k.a.: na Low quality a.k.a.: na Nationality: Afghanistan Passport no: na National identification no: Afghan national identification card (tazkira) number 44323 na Address: na Listed on: 25 Jan. -

Afghanistan Ghazni Province Land Cover

W # AFGHANISTAN E C Sar-e K har Dew#lak A N # GHAZNI PROVINCE Qarah Qowl( 1) I Qarkh Kamarak # # # # # Regak # # Gowshak # # # Qarah Qowl( 2) R V Qada # # # # # # Bandsang # # Dopushta Panqash # # # # # # # Qashkoh Kholaqol # LAND COVER MAP # Faqir an O # Sang Qowl Rahim Dad # # Diktur (1) # Owr Mordah Dahane Barikak D # Barigah # # # Sare Jiska # Baday # # Kheyr Khaneh # Uchak # R # Jandad # # # # # # # # # # Shakhalkhar Zardargin Bumak # # Takhuni # # # # # # # Karez Nazar # Ambolagh # # # # # # Barikak # # Hesar # # # # # Yarum # # # A P # # # # # # Kataqal'a Kormurda # # # # Qeshlaqha Riga Jusha Tar Bulagh # # # # # # ## # # # # # # # # # # # Ahangari # # Kuz Foladay # Minqol # # # Syahreg (2) # # # Maqa # Sanginak # # Baghalak # # # # # # # # # Sangband # Orka B aba # Godowl # Nayak # # # Gadagak # # # # Kota Khwab Altan # # Bahram # # # Katar # # # Barik # Qafak # Qargatak # # # # # # Garmak (3) # # # # # # # # # # Ternawa # # # Kadul # # # # Ghwach # K # # Ata # # # Dandab # # # # # Qole Khugan Sewak (2) Sorkh Dival # # # # # # # # Qabzar (2) # # Bandali # Ajar # Shebar # Hajegak # Sawzsang Podina N ## # # Churka # Nala # # # # # # # Qabzar-1 Turgha # Tughni # Warzang Sultani # # # # # # # # # # # # # Ramzi Qureh Now Juy Negah # # # # # # # # Shew Qowl # Syahsangak A # # # # # # # O # Diktur (2) # Kajak # # Mar Bolagh R V # Ajeda # Gola Karizak # # # Navor Sham # # Dahane Yakhshi Kolukh P # # # # AIMS Y Tanakhak Qal'a-i Dasht I Qole Aymad # Kotal Olsenak Mianah Bed # # # # N Tarbolagh Mar qolak Minqolak Sare Bed Sare Kor ya Ta`ina -

Badghis Province

AFGHANISTAN Badghis Province District Atlas April 2014 Disclaimers: The designations employed and the presentation of material on this map do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. http://afg.humanitarianresponse.info [email protected] AFGHANISTAN: Badghis Province Reference Map 63°0'0"E 63°30'0"E 64°0'0"E 64°30'0"E 65°0'0"E Legend ^! Capital Shirintagab !! Provincial Center District ! District Center Khwajasabzposh Administrative Boundaries TURKMENISTAN ! International Khwajasabzposh Province Takhta Almar District 36°0'0"N 36°0'0"N Bazar District Distirict Maymana Transportation p !! ! Primary Road Pashtunkot Secondary Road ! Ghormach Almar o Airport District p Airfield River/Stream ! Ghormach Qaysar River/Lake ! Qaysar District Pashtunkot District ! Balamurghab Garziwan District Bala 35°30'0"N 35°30'0"N Murghab District Kohestan ! Fa r y ab Kohestan Date Printed: 30 March 2014 08:40 AM Province District Data Source(s): AGCHO, CSO, AIMS, MISTI Schools - Ministry of Education ° Health Facilities - Ministry of Health Muqur Charsadra Badghis District District Projection/Datum: Geographic/WGS-84 Province Abkamari 0 20 40Kms ! ! ! Jawand Muqur Disclaimers: Ab Kamari Jawand The designations employed and the presentation of material !! District p 35°0'0"N 35°0'0"N Qala-e-Naw District on this map do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, Qala-i-Naw Qadis city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation District District of its frontiers or boundaries. -

Name (Original Script): رﺎﻔ ﻐ ﻟادﺑ ﻋ ﯽﺷ ﯾر ﻗ دﺑ ﻋ ﯽﻧ ﻐ ﻟا

Information updated: Name: 1: ABDUL GHAFAR 2: QURISHI 3: ABDUL GHANI 4: na ال غ نی ع بد ق ری شی ع بدال غ فار :(Name (original script Title: Maulavi Designation: Repatriation Attache, Taliban Embassy, Islamabad, Pakistan DOB: a) 1970 b) 1967 POB: Turshut village, Wursaj District, Takhar Province, Afghanistan Good quality a.k.a.: Abdul Ghaffar Qureshi Low quality a.k.a.: na Nationality: Afghan Passport no.: Afghan passport number D 000933 issued in Kabul on 13 Sep. 1998 National identification no.: Afghan national identification card (tazkira) number 55130 Address: Khairkhana Section Number 3, Kabul, Afghanistan Name: 1: SAYED 2: MOHAMMAD 3: AZIM 4: AGHA Title: Maulavi Designation: employee of thePassport and Visa Department of the Taliban regime DOB: Approximately 1966 POB: Kandahar province, Afghanistan *Good quality a.k.a.: na a) Sayed Mohammad Azim Agha b) Agha Saheb Low quality a.k.a.: na Nationality: Afghan Passport no.: na National identification no.: na Address: na Name: 1: MOHAMMAD 2: AHMADI 3: na 4: na احمدی محمد :(Name (original script Title: a) Mullah b) Haji Designation: a) President of Central Bank (Da Afghanistan Bank) under the Taliban regime b) Minister of Finance under the Taliban regime DOB: Approximately 1963 POB: a) Daman District, Kandahar Province, Afghanistan b) Pashmul village, Panjwai District, Kandahar Province, Afghanistan Good quality a.k.a.: na Low quality a.k.a.: na Nationality: Afghan Passport no.: na National identification no.: na Address: na Name: 1: SALEH 2: MOHAMMAD 3: KAKAR 4: AKHTAR MUHAMMAD محمد اخ