Chilean Wine Law Nathan Wages

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spanish Wine & Extra Virgin Olive Oil Selection

Spanish Wine & Extra Virgin Olive Oil Selection ORIGIN ORIGIN FOOBESPAIN INTERNATIONAL trajectory has always been marked by a continuous learning of different cultures and international markets and the search for wine producers with an interesting and suitable portfolio for these markets. The major premise of FOOBESPAIN INTERNATIONAL is to harness this market knowledge to offer a wide range of innovative wine brands tailored to our costumers needs. CONTACT BUSINESS PHILOSOPHY FOOBESPAIN INTERNACIONAL devotes its business to commercial representation of [email protected] wineries at international and national level. Foobespain has a long marketing and sale +34 926 513 167 of wine with high added value which, in turn, great value for the price. FOOBESPAIN Avenida de la Mancha, 80 6º C already has an experience of more than 10 years as a commercial representative of 02008 Albacete - Spain wineries and currently exports more than 25 countries to international level. It also offers commercial and marketing support to its customers throughout the world. DEHESA DEL CARRIZAL Dehesa del Carrizal is a Vino de Pago, the highest category accord- ing The oldest grapevines of Cabernet Sauvignon have grown at Dehesa to Spanish wine law. It is a DOP (Denominación de Origen Protegida - del Carrizal since 1987. They were later joined by Syrah, Merlot. Protected Designation of Origin) reserved for those few wineries and The acid soils of the siliceous Mediterranean mountains, a humid vineyards which carry out the whole process -from the grape to the climate and 800 metres of altitude create the perfect particular micro bottle- within the limits of the Pago or estate. -

Wines of Chile

PREVIEWCOPY Wines of South America: Chile Version 1.0 by David Raezer and Jennifer Raezer © 2012 by Approach Guides (text, images, & illustrations, except those to which specific attribution is given) All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, without permission in writing from the publisher. Further, this book is licensed for your personal enjoyment only. This book may not be resold or given away to other people. If you would like to share this book with another person, please purchase an additional copy for each recipient. Approach Guides and the Approach Guides logo are the property of Approach Guides LLC. Other marks are the prop- erty of their respective owners. Although every effort was made to ensure that the information was as accurate as possible, we accept no responsibility for any loss, damage, injury, or inconvenience sustained by anyone using this guidebook. Approach Guides New York, NY www.approachguides.com PREVIEWISBN: 978-1-936614-36-3COPY This Approach Guide was produced in collaboration with Wines of Chile. Contents Introduction Primary Grape Varieties Map of Winegrowing Regions NORTH Elqui Valley Limarí Valley CENTRAL Aconcagua Valley * Cachapoal Valley Casablanca Valley * Colchagua Valley * Curicó Valley Maipo Valley * Maule Valley San Antonio Valley * SOUTH PREVIEWCOPY Bío Bío Valley * Itata Valley Malleco Valley Vintages About Approach Guides Contact Free Updates and Enhancements More from Approach Guides More from Approach Guides Introduction Previewing this book? Please check out our enhanced preview, which offers a deeper look at this guidebook. The wines of South America continue to garner global recognition, fueled by ongoing quality im- provements and continued attractive price points. -

Epidemiology of Dog Bite Incidents in Chile: Factors Related to the Patterns of Human-Dog Relationship

animals Article Epidemiology of Dog Bite Incidents in Chile: Factors Related to the Patterns of Human-Dog Relationship Carmen Luz Barrios 1,2,*, Carlos Bustos-López 3, Carlos Pavletic 4,†, Alonso Parra 4,†, Macarena Vidal 2, Jonathan Bowen 5 and Jaume Fatjó 1 1 Cátedra Fundación Affinity Animales y Salud, Universitat Autónoma de Barcelona, Parque de Investigación Biomédica de Barcelona, C/Dr. Aiguader 88, 08003 Barcelona, Spain; [email protected] 2 Escuela de Medicina Veterinaria, Facultad de Ciencias, Universidad Mayor, Camino La Pirámide 5750, Huechuraba, Región Metropolitana 8580745, Chile; [email protected] 3 Departamento de Ciencias Básicas, Facultad de Ciencias, Universidad Santo Tomás, Av. Ejército Libertador 146, Santiago, Región Metropolitana 8320000, Chile; [email protected] 4 Departamento de Zoonosis y Vectores, Ministerio de Salud, Enrique Mac Iver 541, Santiago, Región Metropolitana 8320064, Chile; [email protected] (C.P.); [email protected] (A.P.) 5 Queen Mother Hospital for Small Animals, Royal Veterinary College, Hawkshead Lane, North Mymms, Hertfordshire AL9 7TA, UK; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +56-02-3281000 † These authors contributed equally to this work. Simple Summary: Dog bites are a major public health problem throughout the world. The main consequences for human health include physical and psychological injuries of varying proportions, secondary infections, sequelae, risk of transmission of zoonoses and surgery, among others, which entail costs for the health system and those affected. The objective of this study was to characterize epidemiologically the incidents of bites in Chile and the patterns of human-dog relationship involved. The results showed that the main victims were adults, men. -

September 2000 Edition

D O C U M E N T A T I O N AUSTRIAN WINE SEPTEMBER 2000 EDITION AVAILABLE FOR DOWNLOAD AT: WWW.AUSTRIAN.WINE.CO.AT DOCUMENTATION Austrian Wine, September 2000 Edition Foreword One of the most important responsibilities of the Austrian Wine Marketing Board is to clearly present current data concerning the wine industry. The present documentation contains not only all the currently available facts but also presents long-term developmental trends in special areas. In addition, we have compiled important background information in abbreviated form. At this point we would like to express our thanks to all the persons and authorities who have provided us with documents and personal information and thus have made an important contribution to the creation of this documentation. In particular, we have received energetic support from the men and women of the Federal Ministry for Agriculture, Forestry, Environment and Water Management, the Austrian Central Statistical Office, the Chamber of Agriculture and the Economic Research Institute. This documentation was prepared by Andrea Magrutsch / Marketing Assistant Michael Thurner / Event Marketing Thomas Klinger / PR and Promotion Brigitte Pokorny / Marketing Germany Bertold Salomon / Manager 2 DOCUMENTATION Austrian Wine, September 2000 Edition TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Austria – The Wine Country 1.1 Austria’s Wine-growing Areas and Regions 1.2 Grape Varieties in Austria 1.2.1 Breakdown by Area in Percentages 1.2.2 Grape Varieties – A Brief Description 1.2.3 Development of the Area under Cultivation 1.3 The Grape Varieties and Their Origins 1.4 The 1999 Vintage 1.5 Short Characterisation of the 1998-1960 Vintages 1.6 Assessment of the 1999-1990 Vintages 2. -

Latitud 90 Get Inspired.Pdf

Dear reader, To Latitud 90, travelling is a learning experience that transforms people; it is because of this that we developed this information guide about inspiring Chile, to give you the chance to encounter the places, people and traditions in most encompassing and comfortable way, while always maintaining care for the environment. Chile offers a lot do and this catalogue serves as a guide to inform you about exciting, adventurous, unique, cultural and entertaining activities to do around this beautiful country, to show the most diverse and unique Chile, its contrasts, the fascinating and it’s remoteness. Due to the fact that Chile is a country known for its long coastline of approximately 4300 km, there are some extremely varying climates, landscapes, cultures and natures to explore in the country and very different geographical parts of the country; North, Center, South, Patagonia and Islands. Furthermore, there is also Wine Routes all around the country, plus a small chapter about Chilean festivities. Moreover, you will find the most important general information about Chile, and tips for travellers to make your visit Please enjoy reading further and get inspired with this beautiful country… The Great North The far north of Chile shares the border with Peru and Bolivia, and it’s known for being the driest desert in the world. Covering an area of 181.300 square kilometers, the Atacama Desert enclose to the East by the main chain of the Andes Mountain, while to the west lies a secondary mountain range called Cordillera de la Costa, this is a natural wall between the central part of the continent and the Pacific Ocean; large Volcanoes dominate the landscape some of them have been inactive since many years while some still present volcanic activity. -

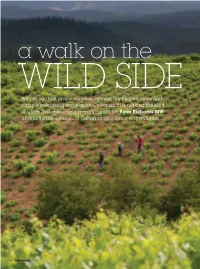

Peter Richards MW on Chile for Imbibe

a walk on the WILD SIDE With its oddball grape varieties, ancient dry-farmed vines and funky winemaking techniques, Chile’s south is making the kind of wines that restaurants are crying out for. Peter Richards MW abandons the comforts of Cabernet Sauvignon to investigate 64 imbibe.com Chile2.indd 64 4/23/2015 4:15:29 PM SOUTHERN CHILE MAIN & ABOVE: EXPLORING THE VINEYARDS OF ITATA. FAR RIGHT: HARVEST TIME AT GARCIA + SCHWADERER s Chile really worth the effort? It’s out via Carmenère, Pinot Noir and Syrah. host of other (often unidentifi ed) varieties a question – often expressed as a Yet still, the perception persists of a grew on granite soils amid rolling hills Iresigned reaction – that is fairly country that delivers solid, maybe ever- and a milder, more temperate climate widespread in the on-trade. Perhaps improving wines but which neither make than warmer areas to the north. it’s understandable, given how many the fi nest partners for food, nor have the The hills around the port city of brilliant wines from all over the globe capacity to get people excited – be they Concepción are considered Chile’s longest vie for attention in our bustling and sommeliers or diners. established vineyard, and it’s a sobering colourful marketplace, including tried This, of course, begs the question: thought that, given it was fi rst developed and tested favourites. what does get people excited when it in the mid- to late-16th century by Jesuit But it’s also based on a missionaries, this area has more conception of Chile as somewhat winemaking history than the predictable and limited in both great estates of the Médoc. -

1000 Best Wine Secrets Contains All the Information Novice and Experienced Wine Drinkers Need to Feel at Home Best in Any Restaurant, Home Or Vineyard

1000bestwine_fullcover 9/5/06 3:11 PM Page 1 1000 THE ESSENTIAL 1000 GUIDE FOR WINE LOVERS 10001000 Are you unsure about the appropriate way to taste wine at a restaurant? Or confused about which wine to order with best catfish? 1000 Best Wine Secrets contains all the information novice and experienced wine drinkers need to feel at home best in any restaurant, home or vineyard. wine An essential addition to any wine lover’s shelf! wine SECRETS INCLUDE: * Buying the perfect bottle of wine * Serving wine like a pro secrets * Wine tips from around the globe Become a Wine Connoisseur * Choosing the right bottle of wine for any occasion * Secrets to buying great wine secrets * Detecting faulty wine and sending it back * Insider secrets about * Understanding wine labels wines from around the world If you are tired of not know- * Serve and taste wine is a wine writer Carolyn Hammond ing the proper wine etiquette, like a pro and founder of the Wine Tribune. 1000 Best Wine Secrets is the She holds a diploma in Wine and * Pairing food and wine Spirits from the internationally rec- only book you will need to ognized Wine and Spirit Education become a wine connoisseur. Trust. As well as her expertise as a wine professional, Ms. Hammond is a seasoned journalist who has written for a number of major daily Cookbooks/ newspapers. She has contributed Bartending $12.95 U.S. UPC to Decanter, Decanter.com and $16.95 CAN Wine & Spirit International. hammond ISBN-13: 978-1-4022-0808-9 ISBN-10: 1-4022-0808-1 Carolyn EAN www.sourcebooks.com Hammond 1000WineFINAL_INT 8/24/06 2:21 PM Page i 1000 Best Wine Secrets 1000WineFINAL_INT 8/24/06 2:21 PM Page ii 1000WineFINAL_INT 8/24/06 2:21 PM Page iii 1000 Best Wine Secrets CAROLYN HAMMOND 1000WineFINAL_INT 8/24/06 2:21 PM Page iv Copyright © 2006 by Carolyn Hammond Cover and internal design © 2006 by Sourcebooks, Inc. -

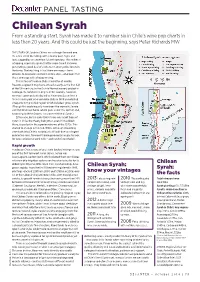

Chilean Syrah from a Standing Start, Syrah Has Made It to Number Six in Chile’S Wine Pop Charts in Less Than 20 Years

PANEL TASTING Chilean Syrah From a standing start, Syrah has made it to number six in Chile’s wine pop charts in less than 20 years. And this could be just the beginning, says Peter Richards MW The sTory of syrah in Chile is not a straightforward one. It’s a tale still in the telling, with a murky past, highs and lows, capped by an uncertain future trajectory. This makes it intriguing, especially given that for some time it has been generating a good deal of excitement among wine lovers in the know. The key thing is that there are many – from drinkers to producers and wine critics alike – who hope that this is one saga with a happy ending. The history of syrah in Chile is a matter of debate. records suggest it may have arrived as early as the first half of the 19th century, in the Quinta Normal nursery project in santiago. Its commercial origins in the country, however, are most commonly attributed to Alejandro Dussaillant, a french immigrant who arrived in Chile in 1874 and planted vineyards in the Curicó region which included ‘gross syrah’. (Though this could equally have been the aromatic savoie variety Mondeuse Noire, which goes under this epithet and, according to Wine Grapes, is a close relative of syrah.) either way, by the early 1990s there was scant trace of syrah in Chile, the theory being that, even if it had been there, it was lost in the agrarian reforms of the 1970s. This started to change in the mid-1990s. -

The Evolution of the Location of Economic Activity in Chile in The

Estudios de Economía ISSN: 0304-2758 [email protected] Universidad de Chile Chile Badia-Miró, Marc The evolution of the location of economic activity in Chile in the long run: a paradox of extreme concentration in absence of agglomeration economies Estudios de Economía, vol. 42, núm. 2, diciembre, 2015, pp. 143-167 Universidad de Chile Santiago, Chile Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=22142863007 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative TheEstudios evolution de Economía. of the location Vol. 42 of -economic Nº 2, Diciembre activity in2015. Chile… Págs. / Marc143-167 Badia-Miró 143 The evolution of the location of economic activity in Chile in the long run: a paradox of extreme concentration in absence of agglomeration economies*1 La evolución de la localización de la actividad económica en Chile en el largo plazo: la paradoja de un caso de extrema concentración en ausencia de fuerzas de aglomeración Marc Badia-Miró** Abstract Chile is characterized as being a country with an extreme concentration of the economic activity around Santiago. In spite of this, and in contrast to what is found in many industrialized countries, income levels per inhabitant in the capital are below the country average and far from the levels in the wealthiest regions. This was a result of the weakness of agglomeration economies. At the same time, the mining cycles have had an enormous impact in the evolution of the location of economic activity, driving a high dispersion at the end of the 19th century with the nitrates (very concentrated in the space) and the later convergence with the cooper cycle (highly dispersed). -

Talking About Wine 11

11 Talking about wine 1 Put the conversation in the correct order. a 1 waiter: Would you like to order some wine with your meal? b woman: Yes, a glass of Pinot Grigio, please. c waiter: The Chardonnay is sweeter than the Sauvignon Blanc. d man: We’d like two glasses of red to go with our main course. Which is smoother, the Chianti or the Bordeaux? e waiter: Well, they are both excellent wines. I recommend the Bordeaux. It’s more full-bodied than the Chianti and it isn’t as expensive. f man: Yes, please. Which is sweeter, the Chardonnay or the Sauvignon Blanc? g man: Right. I’ll have a glass of Chardonnay, then. Sarah, you prefer something drier, don’t you? h man: OK then, let’s have the Bordeaux. i waiter: Certainly, madam. And what would you like with your main course? j woman: Yes, a bottle of sparkling water, please. k waiter: Thank you, sir. Would you like some mineral water? l 12 waiter: OK, so that’s a glass of Chardonnay, a glass of Pinot Grigio, two glasses of Bordeaux and a bottle of sparkling mineral water. 2 Find the mistakes in each sentence and correct them. 1 The Chilean Merlot is not more as expensive as the French. 2 The Riesling is sweet than the Chardonnay. 3 The Pinot Grigio is drier as the Sauvignon Blanc. 4 Chilean wine is most popular than Spanish. 5 A Chianti is no as full-bodied as a good Bordeaux. 6 Champagne is more famous the sherry. -

Report on Cartography in the Republic of Chile 2011 - 2015

REPORT ON CARTOGRAPHY IN CHILE: 2011 - 2015 ARMY OF CHILE MILITARY GEOGRAPHIC INSTITUTE OF CHILE REPORT ON CARTOGRAPHY IN THE REPUBLIC OF CHILE 2011 - 2015 PRESENTED BY THE CHILEAN NATIONAL COMMITTEE OF THE INTERNATIONAL CARTOGRAPHIC ASSOCIATION AT THE SIXTEENTH GENERAL ASSEMBLY OF THE INTERNATIONAL CARTOGRAPHIC ASSOCIATION AUGUST 2015 1 REPORT ON CARTOGRAPHY IN CHILE: 2011 - 2015 CONTENTS Page Contents 2 1: CHILEAN NATIONAL COMMITTEE OF THE ICA 3 1.1. Introduction 3 1.2. Chilean ICA National Committee during 2011 - 2015 5 1.3. Chile and the International Cartographic Conferences of the ICA 6 2: MULTI-INSTITUTIONAL ACTIVITIES 6 2.1 National Spatial Data Infrastructure of Chile 6 2.2. Pan-American Institute for Geography and History – PAIGH 8 2.3. SSOT: Chilean Satellite 9 3: STATE AND PUBLIC INSTITUTIONS 10 3.1. Military Geographic Institute - IGM 10 3.2. Hydrographic and Oceanographic Service of the Chilean Navy – SHOA 12 3.3. Aero-Photogrammetric Service of the Air Force – SAF 14 3.4. Agriculture Ministry and Dependent Agencies 15 3.5. National Geological and Mining Service – SERNAGEOMIN 18 3.6. Other Government Ministries and Specialized Agencies 19 3.7. Regional and Local Government Bodies 21 4: ACADEMIC, EDUCATIONAL AND TRAINING SECTOR 21 4.1 Metropolitan Technological University – UTEM 21 4.2 Universities with Geosciences Courses 23 4.3 Military Polytechnic Academy 25 5: THE PRIVATE SECTOR 26 6: ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS AND ACRONYMS 28 ANNEX 1. List of SERNAGEOMIN Maps 29 ANNEX 2. Report from CENGEO (University of Talca) 37 2 REPORT ON CARTOGRAPHY IN CHILE: 2011 - 2015 PART ONE: CHILEAN NATIONAL COMMITTEE OF THE ICA 1.1: Introduction 1.1.1. -

A Brief History of the International Regulation of Wine Production

A Brief History of the International Regulation of Wine Production The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation A Brief History of the International Regulation of Wine Production (2002 Third Year Paper) Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:8944668 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA A Brief History of the International Regulation of Wine Production Jeffrey A. Munsie Harvard Law School Class of 2002 March 2002 Submitted in satisfaction of Food and Drug Law required course paper and third-year written work require- ment. 1 A Brief History of the International Regulation of Wine Production Abstract: Regulations regarding wine production have a profound effect on the character of the wine produced. Such regulations can be found on the local, national, and international levels, but each level must be considered with the others in mind. This Paper documents the growth of wine regulation throughout the world, focusing primarily on the national and international levels. The regulations of France, Italy, Germany, Spain, the United States, Australia, and New Zealand are examined in the context of the European Community and United Nations. Particular attention is given to the diverse ways in which each country has developed its laws and compromised between tradition and internationalism. I. Introduction No two vineyards, regions, or countries produce wine that is indistinguishable from one another.