September 2000 Edition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2018 Losonci Pinot Gris Matra, Hungary

2018 Losonci Pinot Gris Matra, Hungary Bálint Losonci entered the wine business as a writer for the wine magazine Borbarát under László Alkonyi. He was exposed to a whole world of Hungarian wines in the late 1990s that was just waking up after Communism. He then apprenticed under Gábor Karner (whom he found via Borbarát), and joined a few other liked minded small producers who believed in the future potential of the Mátra appellation. Hungary’s Mátra appellation is quietly the second largest in the country (7500+ hectares), but has been dominated by just a few larger industrial players – perhaps a bit of a Soviet cooperative era hangover. The typical vine density is designed for large tractors and there’s a disturbing amount of Müller-Thurgau and Chasselas geared more for table grape yields than wine. He and others greatly increased vine density, planted native grapes, moved to organic farming, and drastically reduced yields. In the cellar, the main tenants are native fermentation and no other additions other than SO2. Given the wines typical of the area, all of this was somewhat unheard of on a commercial level. He continues to experiment and push himself, but what remains constant is his unwavering community oriented mindset and desire to put Mátra back on the wine map. His vineyards and wines reflect this drive, ambition and generosity. VINEYARDS Roughly 8 hectares are spread across the villages of Gyöngyöspata, Gyöngyöstarján and Nagyréde (single vineyards include Gereg, Tamás-hegy, Sárosberek, Peres, Virág-domb, Oroszi, and Lógi). The first thing Bálint did was plant in between the existing rows (pre Communist era vine density), retrained the vines to drop yield to maximum 1 kilo per plant, and transitioned to organic farming. -

1.2 Weingartenflächen Und Flächenanteile Der Rebsorten EN

1. Vineyard areas and areas under vine by grape variety Austrian Wine statistics report 1.2 Vineyard areas and areas under vine by grape variety 2 The data in this section is based on the 2015 Survey of Area under Vine, as well as feedback from the wine-producing federal states of Niederösterreich (Lower Austria), Burgenland, Steiermark (Styria) and Wien (Vienna). The main source of data for the 2015 Survey of Area under Vine was the Wein-ONLINE system operated by the Federal Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry, Environment and Water Management (BMNT). Data from the remaining federal states was collected by means of a questionnaire (primary data collection). Information relating to the (approved) nurseries was provided by the Burgenland and Lower Austrian Chambers of Agriculture and the Styrian state government (Agricultural Research Centre). According to the 2015 Survey of Area under Vine, Austria’s vineyards occupied 45,574 hectares. The planted vineyard area was 45,439 ha, which corresponds to 94 ha less (or a 0.2% decrease) in comparison to the 2009 Survey of Area under Vine. The long-running trend that suggested a shift away from white wine and towards red was quashed by the 2015 Survey of Area under Vine. While the white wine vineyard area increased by 2.3% to 30,502 ha compared to 2009, the red wine area decreased by 4.9% to 14,937 ha. Figure 1 shows the evolution of Austrian viticulture after the Second World War. The largest area under vine was recorded in 1980 at 59,432 ha. From 1980 onwards, the white wine vineyard area has continuously decreased, while the red wine vineyard area has expanded. -

2018 Heimann Kadarka Szekszárd, Hungary

2018 Heimann Kadarka Szekszárd, Hungary The Szekszárd appellation was originally established by the Each grape is then aged separately as well. Only the Celts, flourished under the Romans (Emperor Probus), Cabernet Franc sees new oak aging. The final blend was continued under the Cistercian Abbeys, and even survived bottled in July of 2015. Turkish occupation due to the high tax revenue the wines NOTES & PAIRINGS generated. Once the Turks were pushed out, modern day Serbians were being pushed north by said Turks and brought The Heimann family continues to narrow down what, where the Kadarka grape with them. Up until this point, the and how with Kadarka. A grape that once covered over appellation was almost entirely white wine. Since then 60,000 hectares in Hungary was less than 400 hectares post Kékfrankos and a variety of Bordeaux varieties (Cab Franc and Phylloxera and Communism. They’ve been narrowing down Merlot mostly) have taken firmly to the region. These grapes in the clonal selection, farming organically, and are now particular also survived under Communism while many of the narrowing down specific sites. While usually very Pinot like in native white and red grapes did not fair so well, namely terms of weight and structure, in 2018 they had to dodge Kadarka. Backing up a bit, after the Turks were pushed out the some impending rain in September and harvested earlier very wine savvy Swabians were also incentivized to resettle than expected. They were mowing cover crops low and even the area. Where the Serbians brought a key red grape, the dropping leaves to get it ready. -

Achraf Iraqui Sommelier: Hugo Arias Sanchez Beverage Director: Darlin Kulla

BY THE GLASS 2 - 3 SPARKLING 4 WHITES 5 - 7 ROSÉ & SKIN CONTACT 8 REDS 9 - 17 DESSERT 18 LIQUOR 19-22 COCKTAILS 23 20% OFF ALL BOTTLED WINE TO ENJOY AT HOME SOMMELIER: ACHRAF IRAQUI SOMMELIER: HUGO ARIAS SANCHEZ BEVERAGE DIRECTOR: DARLIN KULLA WINTER 2020 SPARKLING, ROSÉ & SKIN CONTACT BY THE GLASS ‘ SPARKLING BY THE GLASS CONCA D’ORO, ‘BRUT’ 12 Excellent aperitif with fresh, fruity apple and grapefruit aromas with a BY THE GLASS very delicate and refreshing taste Prosecco, Veneto, IT / NV APOLLONI VINEYARDS 13 DOMAINE BENOIT BADOZ, ‘BRUT ROSÉ’ 18 Pinot Noir With more than 400 years of history, this winery makes a very Light and fresh with tart strawberry, cherry and floral aromas elegant, delicate and mineral-driven sparkling that emphasizes with a nice clean finish toast and citrus flavors Willamette Valley / 2017 Crémant du Jura, FR / NV DOLORES CABRERA FERNANDEZ, ‘LA 16 LAURENT PERRIER, ‘LA CUVÉE BRUT’ 28 Defined by its high content of Chardonnay in the blend, this ARAUCARIA’ champagne is all about finesse, freshness and purity with Listan Negro citrus-driven notes and a very dry finish From the Canary Islands, this Rosé has vibrant notes Champagne, FR / NV of red and black fruit, cracked peppercorn and purple flowers Tenerife, Canary Islands, SP / 2018 AR LENOBLE, ‘BRUT ROSÉ’ 28 Mostly Chardonnay with just the right amount of Pinot Noir, WEINGUT HEINRICH, ‘NAKED WHITE’ 15 this amazing Rosé is defined by its richness and spice with fine citrus flavors Chardonnay/Pinot Blanc/Neuburger Champagne, FR / NV Balanced orange wine with notes -

Riesling Originated in the Rhine Region of Germany

Riesling Originated in the Rhine region of Germany 1st mention of it was in 1435 when a noble of Katzenelbogen in Rüsselsheim listed it at 22 schillings for Riesling cuttings Riesling comes from the word “Reisen” means “fall” in German…grapes tend to fall off vines during difficult weather at bud time Riesling does very well in well drained soils with an abundance of light, it likes the cool nights. It ripens late so cool nights are essential for retaining balance Momma and papa Parentage: DNA analysis says that • An aromatic grape with high Gouais Blanc was a parent. acidity Uncommon today, but was a popular • Grows in cool regions wine among the peasants during the • Shows Terroir: sense of place middle ages. The other parent could have been a cross of wild vines and Traminer. Riesling flavors and aromas: lychee, honey, apricot, green apples, grapefruit, peach, goose- berry, grass, candle wax, petrol and blooming flowers. Aging Rieslings can age due to the high acidity. Some German Rieslings with higher sugar levels are best for cellaring. Typically they age for 5-15 years, 10-20 years for semi sweet and 10-30 plus years for sweet Rieslings Some Rieslings have aged 100 plus years. Likes and Dislikes: Many Germans prefer the young fruity Rieslings. Other consumers prefer aged They get a petrol note similar to tires, rubber or kerosene. Some see it as fault while others quite enjoy it. It can also be due to high acidity, grapes that are left to hang late into the harvest, lack of water or excessive sun exposure. -

How to Buy Eiswein Dessert Wine

How to Buy Eiswein Dessert Wine Eiswein is a sweet dessert wine that originated in Germany. This "late harvest" wine is traditionally pressed from grapes that are harvested after they freeze on the vine. "Eiswein" literally means "ice wine," and is called so on some labels. If you want to buy eiswein, know the country and the method that produced the bottle to find the best available "ice wine" for your budget. Does this Spark an idea? Instructions 1. o 1 Locate a local wine store or look on line for wine sellers who carry eiswein. o 2 Look for a bottle that fits your price range. German and Austrian Eisweins, which follow established methods of harvest and production, are the European gold standard. However, many less expensive, but still excellent, ice wines come from Austria, New Zealand, Slovenia, Canada and the United States. Not all producers let grapes freeze naturally before harvesting them at night. This time-honored and labor-intensive method of production, as well as the loss of all but a few drops of juice, explains the higher price of traditionally produced ice wine. Some vintners pick the grapes and then artificially freeze them before pressing. Manage Cellar, Share Tasting Notes Free, powerful, and easy to use! o 3 Pick a colorful and fragrant bouquet. Eiswein is distinguished by the contrast between its fragrant sweetness and acidity. A great eiswein is both rich and fresh. Young eisweins have tropical fruit, peach or berry overtones. Older eisweins suggest caramel or honey. Colors can range from white to rose. -

BUBBLES PINOT NOIR-CHARDONNAY, Pierre

Wines By The Glass BUBBLES PINOT NOIR-CHARDONNAY, Pierre Paillard, ‘Les Parcelles,’ Bouzy, Grand Cru, 25 Montagne de Reims, Extra Brut NV -treat yourself to this fizzy delight MACABEO-XARELLO-PARELLADA, Mestres, 'Coquet,' Gran Reserva, 14 Cava, Spain, Brut Nature 2013 -a century of winemaking prowess in every patiently aged bottle ROSÉ OF PINOT NOIR, Val de Mer, France, Brut Nature NV 15 -Piuze brings his signature vibrant acidity to this juicy berried fizz WHITE + ORANGE TOCAI FRIULANO, Mitja Sirk, Venezia Giulia, Friuli, Italy ‘18 14 -he made his first wine at 11; now he just makes one wine-- very well, we think FRIULANO-RIBOLLA GIALLA-chardonnay, Massican, ‘Annia,’ 17 Napa Valley, CA USA ‘17 -from the heart of American wine country, an homage to Northern Italy’s great whites CHENIN BLANC, Château Pierre Bise, ‘Roche aux Moines,’ 16 Savennières, Loire, France ‘15 -nerd juice for everyone! CHARDONNAY, Enfield Wine Co., 'Rorick Heritage,' 16 Sierra Foothills, CA, USA ‘18 -John Lockwood’s single vineyard dose of California sunshine RIESLING, Von Hövel, Feinherb, Saar, Mosel, Germany ‘16 11 -sugar and spice and everything nice TROUSSEAU GRIS, Jolie-Laide, ‘Fanucchi Wood Road,’ Russian River, CA, USA ‘18 15 -skin contact lends its textured, wild beauty to an intoxicating array of fruit 2 Wines By The Glass ¡VIVA ESPAÑA! -vibrant wines sprung from deeply rooted tradition and the passion of a new generation VIURA-MALVASIA-garnacha blanca, Olivier Rivière, ‘La Bastid,’ Rioja, Spain ‘16 16 HONDARRABI ZURI, Itsasmendi, ‘Bat Berri,’ Txakolina -

2016 Maurer Kadarka Újlak Sremska, Serbia

2016 Maurer Kadarka Újlak Sremska, Serbia The Maurer family has been producing wine for four NOTES & PAIRINGS generations. It was during the AustroHungarian Monarchy in Kadarka is a native Balkan grape, which, according to one the 19th century that they moved from Salzburg to the southern theory, originates from the shores of Lake Skadar on the part of the Kingdom of Hungary. They now farm 16 acres of modern AlbaniaMontenegro border. The wine was made land, including 6 acres in the Serbian wine region of Szabadka with no added yeast, fermented in open vat and aged in big directly south of the HungarianSerbian border, and 10 acres in old oak casks for 12 months. There is no added sulphur. the Fruška Gora mountain district in Syrmia, Serbia, located 40 Decant before serving to allow the wine to open up and miles away from Belgrade and bordered by the Danube River release its bouquet. The wine is fruity, spicy and has to the north. beautiful acids. VINEYARDS ANALYTICS & PRONUNCIATION The vineyards are planted with old local varieties such as PRODUCER: Maurer Mézes Fehér, Bakator, Szerémi Zöld. In the Szabadka wine APPELLATION: Sremska region, vines are more than a hundred years old. The oldest VINTAGE: 2016 Kadarka was planted in 1880 and is one of the oldest in the GRAPE COMPOSITION: 100% Kadarka world. These vines are typically cultivated by horse and man CLIMATE: Mild and temperate power. The other part of the estate is in the historic region of SOILS: Sand Szerémség (Syrmia). Some ninety million years ago, the MACERATION & AGING: Fermented in open vat and aged in Fruška Gora mountain in Syrmia was an island in the big old oak casks for 12 months Pannonian sea. -

An Investigation Into the Attitudes of UK Independent Wine Merchants Towards the Wines of Sardinia

An investigation into the attitudes of UK independent wine merchants towards the wines of Sardinia. © The Institute of Masters of Wine 2016. No part of this publication may be reproduced without permission. This publication was produced for private purpose and its accuracy and completeness is not guaranteed by the Institute. It is not intended to be relied on by third parties and the Institute accepts no liability in relation to its use. CONTENTS 1. ABSTRACT 1 2. INTRODUCTION 2 3. RESEARCH CONTEXT AND LITERATURE REVIEW 4 3.1: UK Independent Shops 4 3.2: UK Wine Market 5 3.3: UK Independent Wine Merchants 5 3.4: Wines of Sardinia 7 3.5: Wines of Sardinia in the UK market 8 3.6: Surveys of IWMs 9 3.7: UK consumer studies 9 3.8: Retailer and consumer attitudes 10 4. METHODOLOGY 11 4.1: Overview 11 4.2: Definition of IWMs and Population 11 4.3: Sample Selection 12 4.4: Interviews 12 4.5: Survey Design 13 4.6: Survey Implementation 15 4.7: Analysis 15 5. RESULTS AND ANALYSIS 16 5.1: Overview 16 5.2: Response Rate 16 5.3: The Respondents 17 5.3.1: Specialisation 18 5.3.2: Listings 19 5.3.3: Factors in selling Sardinian Wine 22 5.4: Understanding of Sardinian Wine 25 5.4.1: Engagement 25 5.4.2: Knowledge 26 5.5: Attitudes towards Sardinian Wine 28 5.5.1: Price and Value 30 5.5.2: Grape Varieties 32 5.5.3: Brands 34 5.5.4: Packaging 34 5.5.5: Style 35 5.5.6: Sicily 35 5.6: Other Observations 36 6. -

BUBBLES PINOT NOIR-CHARDONNAY, Pierre

Wines By The Glass BUBBLES PINOT NOIR-CHARDONNAY, Pierre Paillard, ‘Les Parcelles,’ Bouzy, Grand Cru, 25 Montagne de Reims, Extra Brut NV -treat yourself to this fizzy delight XAREL-LO-MACABEU-PARELLADA, Raventós i Blanc, Conca del Riu Anoia, 12 Spain Brut ‘17 -centuries of winemaking prowess in every impeccably produced bottle ROSÉ OF PINOT NOIR, Val de Mer, France, Brut Nature NV 15 -Piuze brings his signature vibrant acidity to this juicy berried fizz WHITE + ORANGE TOCAI FRIULANO, Mitja Sirk, Venezia Giulia, Friuli, Italy ‘18 14 -he made his first wine at 11; now he just makes one wine-- very well, we think CHENIN BLANC, Château Pierre Bise, ‘Clos de Coulaine,’ 15 Savennières, Loire, France ‘16 -nerd juice for everyone! FRIULANO-RIBOLLA GIALLA-chardonnay, Massican, ‘Annia,’ 17 Napa Valley, CA USA ‘17 -from the heart of American wine country, an homage to Northern Italy’s great whites CHARDONNAY, Big Table Farm, ‘The Wild Bee,’ 16 Willamette Valley, OR, USA ‘18 -straddling the divide between old world and new with feet firmly planted in Oregon RIESLING, Von Hövel, Feinherb, Saar, Mosel, Germany ‘16 11 -sugar and spice and everything nice TROUSSEAU GRIS, Jolie-Laide, ‘Fanucchi Wood Road,’ Russian River, CA, USA ‘18 15 -skin contact lends its textured, wild beauty to an intoxicating array of fruit 2 Wines By The Glass ¡VIVA ESPAÑA! -vibrant wines sprung from deeply rooted tradition and the passion of a new generation GODELLO-DONA BLANCA-albariño-treixadura-etc., Fedellos do Couto, 16 ‘Conasbrancas,’ Ribeira Sacra, Spain ‘16 ROSÉ OF SUMOLL-PARELLADA-XAREL-LO, Can Sumoi, ‘La Rosa,’ 11 Penedès, Spain ‘18 MENCÍA-ALBRÍN TINTO, Dominio del Urogallo, ‘Fanfarria,’ Asturias, Spain ‘17 11 GARNACHA TINTORERA-MORAVIA AGRIA, Envínate, ‘Albahra,’ Almansa, 13 Castilla la Mancha, Spain ‘18 TEMPRANILLO-GRACIANO-GARNACHA, Bodega Lanzaga, ‘LZ,’ Rioja, Spain ‘18 12 RED PINOT NOIR, Julia Bertram, ‘Handwerk,’ Ahr, Germany ‘17 15 -let this bona-fide queen of German wine subject you to spätburgunder’s charms GAMAY, Antoine Sunier, Régnié, Beaujolais, France ‘18 13 -Régn-YAY!.. -

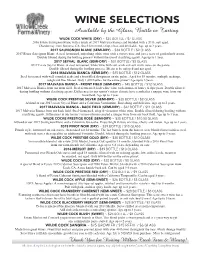

WINE SELECTIONS Available by the Glass, Bottle Or Tasting

WINE SELECTIONS Available by the Glass, Bottle or Tasting WILDE COCK WHITE (DRY) ~ $24 BOTTLE / $7 GLASS 2016 Estate Sauvignon Blanc with a touch of 2017 Malvasia Bianca and blended with a 2016, oak aged, Chardonnay from Sonoma, CA. Steel fermented, crisp, clean and drinkable. Age up to 2 years. 2017 SAUVIGNON BLANC (SEMI-DRY) ~ $34 BOTTLE / $9 GLASS 2017 Estate Sauvignon Blanc. A steel fermented, refreshing white wine with a citrusy nose and just a tease of garden herb aroma. Double filtered during the bottling process without the use of clarifying agents.Age up to 1 year. 2017 SEYVAL BLANC (SEMI-DRY) ~ $31 BOTTLE / $8 GLASS 2017 Estate Seyval Blanc. A steel fermented, white wine with soft acids and soft citrus notes on the palate. Double filtered during the bottling process. Meant to be enjoyed and not aged. 2016 MALVASIA BIANCA (SEMI-DRY) ~ $45 BOTTLE / $12 GLASS Steel fermented with well-rounded acids and a fruit filled dissipation on the palate.Aged for 10 months, multiple rackings, rough and fine filtered. Only 1,600 bottles for the entire planet!Age up to 3 years. 2017 MALVASIA BIANCA - FRONT FIELD (SEMI-DRY) ~ $45 BOTTLE / $12 GLASS 2017 Malvasia Bianca from our front field. Steel-fermented, lush white wine with aromas of honey & ripe pears. Double filtered during bottling without clarifying agents. Differences in our terroir’s micro-climate have resulted in a unique wine from our front field. Age up to 1 year. WILDE COCK PRESTIGE SILVER (SEMI-DRY) ~ $28 BOTTLE / $8 GLASS A blend of our 2017 estate Seyval Blanc and a California Vermentino. -

Produktspezifikation Vorarlberg

P R O D U K T S P E Z I F I K A T I O N gem. VO 1308/2013, Art. 94 für eine „Ursprungsbezeichnung“ gem. Art. 94 a) Zu schützender Name: Vorarlberg b) Beschreibung der wichtigsten analytischen und organoleptischen Eigenschaften der Weine: Das Weinbaugebiet Vorarlberg umfasst eine Rebfläche von 10 ha. Geografisch deckt es sich mit dem Bundesland Vorarlberg. Die Ursprungsbezeichnung Vorarlberg kann für Wein und Qualitätsschaumwein verwendet werden, wobei die Verwendung für Qualitätsschaumwein in der Praxis keine Anwendung findet. Die Bedingungen für die Verwendung von Qualitätsschaumwein entsprechen denjenigen in den g.U.s Nieder- österreich, Burgenland, Steiermark und Wien; sie werden in dieser Produktspezifika- tion nicht angeführt. Eine Aufstellung über die wichtigsten analytischen Parameter ist dem Anhang zu die- ser Produktspezifikation zu entnehmen. Verwendung von „Vorarlberg“ für Wein: Weine der Ursprungsbezeichnung „Vorarlberg“ müssen mit einem der nachstehen- den traditionellen Begriffe gem. österreichischem Weingesetz 2009 (in der geltenden Fassung) am Etikett bezeichnet werden: 1. „Qualitätswein“: Der Saft der Trauben muss ein Mindestmostgewicht von 15°Klosterneuburger Mostwaage (= 9,5 % vol.) aufweisen. 2. „Kabinett“ oder „Kabinettwein“: Der Saft der Trauben muss ein Mindestmostge- wicht von 17° Klosterneuburger Mostwaage (= 11,1 % vol.) aufweisen. 3. „Spätlese“ oder „Spätlesewein“: Wein aus Trauben, die in vollreifem Zustand ge- erntet worden sind. 4. „Auslese“ oder „Auslesewein“: Spätlese, die ausschließlich aus sorgfältig ausgele- senen Trauben - unter Aussonderung aller nicht vollreifen, fehlerhaften und kran- ken Beeren gewonnen wurde. 1 5. „Beerenauslese“ oder „Beerenauslesewein“: Wein aus dem Saft überreifer oder edelfauler Beeren. 6. „Ausbruch“ oder „Ausbruchwein“: Wein, der ausschließlich aus edelfaulen oder überreifen, auf natürliche Weise eingetrockneten Beeren stammt.