Advani to Modi to Yogi, a Hindutva Story Foretold Vidya Subrahmaniam Apr 27, 2017

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Leaders @ G-23

www.fi rstindia.co.in OUR EDITIONS: www.fi rstindia.co.in/epaper/ JAIPUR, AHMEDABAD twitter.com/thefi rstindia & LUCKNOW facebook.com/thefi rstindia instagram.com/thefi rstindia LUCKNOW l SUNDAY, FEBRUARY 28, 2021 l Pages 12 l 3.00 RNI NO. UPENG/2020/04393 l Vol 1 l Issue No. 106 HOPE & BEYOND! These Bar Headed Goose fl ying above Chandlai Lake of Jaipur, remind us of the famous American thriller, The Birds, directed by Alfred Hitchcock! Though the movie spoke a lot about the helplessness, in the face of the inevitable, however, this mesmerising photo by First India’s Photojournalist Suman Sarkar, depicts hope for a better future for all as after almost one year of fi ghting the pandemic, the world has got vaccine to fi ght Covid 19. PM: India can ‘CM GEHLOT’S RAHUL IN TN: BUDGET IS A take world WELFARE BUDGET’ Cong has weakened in last back to eco- CHINESE KNOW friendly toys PM IS ‘SCARED’ decade: Leaders @ G-23 New Delhi: Prime Min- ister Narendra Modi on POLL READY: RaGa attacks Modi over Sino- Kapil Sibal said he & other leaders have gathered to address issues that party Saturday said that the India standoff during his 3-day Tamil Nadu tour is facing now; says party didn’t utilise Ghulam Nabi Azad’s experience ancient toy culture of the country reflects the Editor-In-Chief of Jammu: Senior Con- practice of reuse and First India, Jagdeesh gress leaders Kapil recycling, which is part Chandra, in The New Sibal and Anand Shar- of the Indian lifestyle, JC Show, speaks ma on Saturday stated and added that India about how CM Gehlot that the G-23 or the has the potential to take has emerged as a group of 23 dissenting the world back to eco- hero on national leaders are seeing the friendly toys. -

India's Democracy at 70: Toward a Hindu State?

India’s Democracy at 70: Toward a Hindu State? Christophe Jaffrelot Journal of Democracy, Volume 28, Number 3, July 2017, pp. 52-63 (Article) Published by Johns Hopkins University Press DOI: https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.2017.0044 For additional information about this article https://muse.jhu.edu/article/664166 [ Access provided at 11 Dec 2020 03:02 GMT from Cline Library at Northern Arizona University ] Jaffrelot.NEW saved by RB from author’s email dated 3/30/17; 5,890 words, includ- ing notes. No figures; TXT created from NEW by PJC, 4/14/17 (4,446 words); MP ed- its to TXT by PJC, 4/19/17 (4,631 words). AAS saved by BK on 4/25/17; FIN created from AAS by PJC, 5/26/17 (5,018 words). FIN saved by BK on 5/2/17 (5,027 words); PJC edits as per author’s updates saved as FINtc, 6/8/17, PJC (5,308 words). PGS created by BK on 6/9/17. India’s Democracy at 70 TOWARD A HINDU STATE? Christophe Jaffrelot Christophe Jaffrelot is senior research fellow at the Centre d’études et de recherches internationales (CERI) at Sciences Po in Paris, and director of research at the Centre national de la recherche scientifique (CNRS). His books include Religion, Caste, and Politics in India (2011). In 1976, India’s Constitution of 1950 was amended to enshrine secular- ism. Several portions of the original constitutional text already reflected this principle. Article 15 bans discrimination on religious grounds, while Article 25 recognizes freedom of conscience as well as “the right freely to profess, practise and propagate religion.” Collective as well as indi- vidual rights receive constitutional recognition. -

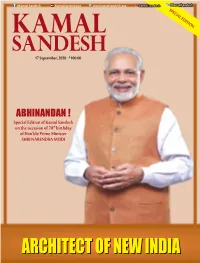

Architect of New India Fortnightly Magazine Editor Prabhat Jha

@Kamal.Sandesh KamalSandeshLive www.kamalsandesh.org kamal.sandesh @KamalSandesh SPECIAL EDITION 17 September, 2020 `100.00 ABHINANDAN ! Special Edition of Kamal Sandesh on the occasion of 70th birthday of Hon’ble Prime Minister SHRI NARENDRA MODI ARCHITECTARCHITECT OFOF NNEWEWArchitect ofII NewNDINDI India KAMAL SANDESHAA 1 Self-reliant India will stand on five Pillars. First Pillar is Economy, an economy that brings Quantum Jump rather than Incremental change. Second Pillar is Infrastructure, an infrastructure that became the identity of modern India. Third Pillar is Our System. A system that is driven by technology which can fulfill the dreams of the 21st century; a system not based on the policy of the past century. Fourth Pillar is Our Demography. Our Vibrant Demography is our strength in the world’s largest democracy, our source of energy for self-reliant India. The fifth pillar is Demand. The cycle of demand & supply chain in our economy is the strength that needs to be harnessed to its full potential. SHRI NARENDRA MODI Hon’ble Prime Minister of India 2 KAMAL SANDESH Architect of New India Fortnightly Magazine Editor Prabhat Jha Executive Editor Dr. Shiv Shakti Bakshi Associate Editors Ram Prasad Tripathy Vikash Anand Creative Editors Vikas Saini Bhola Roy Digital Media Rajeev Kumar Vipul Sharma Subscription & Circulation Satish Kumar E-mail [email protected] [email protected] Phone: 011-23381428, FAX: 011-23387887 Website: www.kamalsandesh.org 04 EDITORIAL 46 2016 - ‘IndIA IS NOT 70 YEARS OLD BUT THIS JOURNEY IS -

Narendra Modi Tops, Yogi Adityanath Enters List

Vol: 23 | No. 4 | April 2017 | R20 www.opinionexpress.in A MONTHLY NEWS MAGAZINE Hindu-Americans divided on Trump’s immigration policy COVER STORY SOARING HIGH The ties between India and Israel were never better The Pioneer Most Powerful Indians in 2017: Narendra Modi tops,OPINI YogiON EXPR AdityanathESS enters list 1 2 OPINION EXPRESS editorial Modi, Yogi & beyond RNI UP–ENG 70032/92, Volume 23, No 4 EDITOR Prashant Tewari – BJP is all set for the ASSOCiate EDITOR Dr Rahul Misra POLITICAL EDITOR second term in 2019 Prakhar Misra he surprise appointment of Yogi Adityanath as Uttar Pradesh Chief Minister post BUREAU CHIEF party’s massive victory in the recently concluded assembly elections indicates that Gopal Chopra (DELHI), Diwakar Shetty BJP/RSS are in mission mode for General Election 2019. The new UP CM will (MUMBAI), Sidhartha Sharma (KOLKATA), T ensure strict saffron legislation, compliance and governance to Lakshmi Devi (BANGALORE ) DIvyash Bajpai (USA), KAPIL DUDAKIA (UNITED KINGDOM) consolidate Hindutva forces. The eighty seats are vital to BJP’s re- Rajiv Agnihotri (MAURITIUS), Romil Raj election in the next parliament. PM Narendra Modi is world class Bhagat (DUBAI), Herman Silochan (CANADA), leader and he is having no parallel leader to challenge his suprem- Dr Shiv Kumar (AUS/NZ) acy in the country. In UP, poor Akhilesh and Rahul were just swept CONTENT partner aside-not by polarization, not by Hindu consolidation but simply by The Pioneer Modi’s far higher voltage personality. Pratham Pravakta However the elections in five states have proved that BJP is not LegaL AdviSORS unbeatable. -

Written Testimony of Musaddique Thange Communications Director Indian American Muslim Council (IAMC)

Written Testimony of Musaddique Thange Communications Director Indian American Muslim Council (IAMC) for ‘Challenges & Opportunities: The Advancement of Human Rights in India’ by Tom Lantos Human Rights Commission June 7, 2016 1334 Longworth House Office Building Challenges & Opportunities: The Advancement of Human Rights in India Tom Lantos Human Rights Commission - June 7, 2016 Table of Contents Table of Contents Introduction Religious violence, hate speeches and other forms of persecution The Hindu Nationalist Agenda Religious Violence Hate / Provocative speeches Cow related violence - killing humans to protect cows Ghar Wapsi and the Business of Forced and Fraudulent Conversions Love Jihad Counter-terror Scapegoating of Impoverished Muslim Youth Curbs on Religious Freedoms of Minorities Caste based reservation only for Hindus; Muslims and Christians excluded No distinct identity for Sikhs, Buddhists and Jains Anti-Conversion Laws and the Hindu Nationalist Agenda A Broken and Paralyzed Judiciary Myth of a functioning judiciary Frivolous cases and abuse of judicial process Corruption in the judiciary Destruction of evidence Lack of constitutional protections Recommendations US India Strategic Dialogue Human Rights Workers’ Exchange Program USCIRF’s Assessment of Religious Freedom in India Conclusion Appendix A: Hate / Provocative speeches MP Yogi Adityanath (BJP) MP Sakshi Maharaj (BJP) Sadhvi Prachi Arya Sadhvi Deva Thakur Baba Ramdev MP Sanjay Raut (Shiv Sena) Written Testimony - Musaddique Thange (IAMC) 1 / 26 Challenges & Opportunities: The Advancement of Human Rights in India Tom Lantos Human Rights Commission - June 7, 2016 Introduction India is a multi-religious, multicultural, secular nation of nearly 1.25 billion people, with a long tradition of pluralism. It’s constitution guarantees equality before the law, and gives its citizens the right to profess, practice and propagate their religion. -

Date:/9/04/031 ORDER 1 .Vide Order No.05/G-Gaz.-IA/DHC/2021 Dated 29.01.2021, the Hon'ble High Court of Delhi Has Created Three New Labour Courts

GOVERNMENT OF NATIONAL CAPITAL TERRITORY OF DELHI LABOUT DEPARTMENT 5-SHAM NATH MARG, DELHI-110054 F.No.15(16)/Lab/2021//695- 1706 Date:/9/04/031 ORDER 1 .Vide order no.05/G-Gaz.-IA/DHC/2021 Dated 29.01.2021, the Hon'ble High Court of Delhi has created three new Labour Courts. The Labour Courts have been designated as under: S.No Labour COurt no. Ld. Presiding Officer Labour Court-01 2 Smt. Veena Rani Labour Court-02 Sh. Pawan Kumar Matto_ Labour Court-03 Sh. Raj kumar Labour Court-04 Sh Gorakh Nath Pandey Labour Court-05_ Sh. Sanatan Prasad Labour Court-06 Sh. Ramesh Kumar-II 7 Labour Court-07 Ms. Navita kumari Bagha 8 Labour Court-08 Sh. Tarun Yogesh 9 Labour Court-09 Sh. Joginder Prakash Nahar 2. Vide this office order no. F.No. 15(16)Lab/2021/647 dated 08.02.2021, the newly constituted Labour Courts have been transferred cases. All the district Joint Labour Commissioner/Deputy Labour Commissioner shall make reference of new Industrial Disputes to Labour Courts as per Table mentioned below District Area falling under following Police Stations Labour Court South Saket, Neb sarai , Hauz Khas . Malviya Nagar, Mehrauli , Fatehpur Beri, Labour Court No.l Lajpat Nagar, Amar colony. Defence Colony. Lodhi Colony, Hazrat Nizamuddin, Sriniwas Puri, Greater Kailash, Chitranjan Park, Kalkaji, Badarpur, Okhla Indl. Area, Ambedkar Nagar, Kotla Jamia Mubarakpur, Nagar, Sunlight Colony , Sangam vihar, Govind puri , Pul Prahlad puri, , Sarita vihar , Newfriends Colony, Jaitpur Labour Court No.2 South- Vasant Vihar, Vasant Kunj, Mahipalpur, RK. -

Mamata Banerjee to Centre: Send NHRC to Tripura

TELEGRAPH, Online, 29.8.2021 Page No. 0, Size:(0)cms X (0)cms. Telegraph Mamata Banerjee to Centre: Send NHRC to Tripura Her reaction came on a day a Trinamul joining event in Badharghat was attacked by suspected ruling BJP members, leaving three TMC workers injured Chief minister Mamata Banerjee on Saturday dared the BJP-led Centre to send the National Human Rights Commission to Tripura over attacks on her party supporters “every day”. Her reaction came on a day a Trinamul joining event in Badharghat, 6km from Agartala, was attacked by suspected ruling BJP members, leaving three Trinamul workers injured. Three Trinamul student activists also received minor injuries at a college in Unakoti, some 150km from Agartala, when they were celebrating the foundation day of the Trinamul Chhatra Parishad. Will you send teams of National Human Rights Commission only to Bengal? Why were such teams not sent to Tripura...? Our people are attacked by goons there every day,” she said. Tripura BJP spokesperson Nabendu Bhattacharyya dismissed the allegations. Mamata alleged in her virtual address from Calcutta that even cops posted for the security of Trinamul leaders had not been spared. “They received injuries and were not allowed medicines or injection,” she said. She also predicted “khela hobe (her successful Bengal poll cry) in Tripura. She reminded BJP leaders that they did not allow her MPs to visit Assam during the NRC protest there. Her nephew and Trinamul all-India general secretary Abhishek Banerjee warned the BJP that Trinamul would come to power in Tripura in 2023. “Trinamul will form the government in Tripura under the leadership of Mamata Banerjee. -

Why I Became a Hindu

Why I became a Hindu Parama Karuna Devi published by Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Copyright © 2018 Parama Karuna Devi All rights reserved Title ID: 8916295 ISBN-13: 978-1724611147 ISBN-10: 1724611143 published by: Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Website: www.jagannathavallabha.com Anyone wishing to submit questions, observations, objections or further information, useful in improving the contents of this book, is welcome to contact the author: E-mail: [email protected] phone: +91 (India) 94373 00906 Please note: direct contact data such as email and phone numbers may change due to events of force majeure, so please keep an eye on the updated information on the website. Table of contents Preface 7 My work 9 My experience 12 Why Hinduism is better 18 Fundamental teachings of Hinduism 21 A definition of Hinduism 29 The problem of castes 31 The importance of Bhakti 34 The need for a Guru 39 Can someone become a Hindu? 43 Historical examples 45 Hinduism in the world 52 Conversions in modern times 56 Individuals who embraced Hindu beliefs 61 Hindu revival 68 Dayananda Saraswati and Arya Samaj 73 Shraddhananda Swami 75 Sarla Bedi 75 Pandurang Shastri Athavale 75 Chattampi Swamikal 76 Narayana Guru 77 Navajyothi Sree Karunakara Guru 78 Swami Bhoomananda Tirtha 79 Ramakrishna Paramahamsa 79 Sarada Devi 80 Golap Ma 81 Rama Tirtha Swami 81 Niranjanananda Swami 81 Vireshwarananda Swami 82 Rudrananda Swami 82 Swahananda Swami 82 Narayanananda Swami 83 Vivekananda Swami and Ramakrishna Math 83 Sister Nivedita -

Yoga Teacher Training – House of Om

LIVE LOVE INSPIRE HOUSE OF OM MODULE 8 PRACTICE 120 MINS In this Vinyasa Flow we train all the poses of the Warrior series, getting ready to take our training from the physical to beyond HISTORY 60 MINS Yoga has continued evolving and expanding throughout the time that’s why until nowadays it is still alive thanks to these masters that dedicated their life in order to practice and share their knowledge with the world. YOGA NIDRA ROUTINE Also known as Yogic sleep, Yoga Nidra is a state of consciousness between waking and sleeping. Usually induced by a guided meditation HISTORY QUIZ AND QUESTIONS 60 MINS Five closed and two open question will both entertain with a little challenge, and pinpoint what resonated the most with your individual self. REFLECTION 60 MINS Every module you will be writing a reflection. Save it to your own journal as well - you will not only learn much faster, but understand what works for you better. BONUS Mahamrityumjaya Mantra In all spiritual traditions, Mantra Yoga or Meditation is regarded as one of the safest, easiest, and best means of systematically overhauling the patterns of consciousness. HISTORY YOGA HISTORY. MODERN PERIOD Yoga has continued evolving and expanding throughout the time that’s why until nowadays it is still alive thanks to these masters that dedicated their life in order to practice and share their knowledge with the world. In between the classical yoga of Patanjali and the 20th century, Hatha Yoga has seen a revival. Luminaries such as Matsyendranath and Gorakhnath founded the Hatha Yoga lineage of exploration of one’s body-mind to attain Samadhi and liberation. -

All the Nathas Or Nat Hayogis Are Worshippers of Siva and Followers

8ull. Ind. Inst. Hist. Med. Vol. XIII. pp. 4-15. INFLUENCE OF NATHAYOGIS ON TELUGU LITERATURE M. VENKATA REDDY· & B. RAMA RAo·· ABSTRACT Nathayogis were worshippers of Siva and played an impor- tant role in the history of medieval Indian mysticism. Nine nathas are famous, among whom Matsyendranatha and Gorakhnatha are known for their miracles and mystic powers. Tbere is a controversy about the names of nine nathas and other siddhas. Thirty great siddhas are listed in Hathaprad [pika and Hathara- tnaval ] The influence of natha cult in Andhra region is very great Several literary compositions appeared in Telugu against the background of nathism. Nannecodadeva,the author of'Kumar asarnbbavamu mentions sada ngayoga 'and also respects the nine nathas as adisiddhas. T\~o traditions of asanas after Vas istha and Matsyendra are mentioned Ly Kolani Ganapatideva in·sivayogasaramu. He also considers vajrfsana, mukrasana and guptasana as synonyms of siddhasa na. suka, Vamadeva, Matsyendr a and Janaka are mentioned as adepts in SivaY0ga. Navanathacaritra by Gaurana is a work in the popular metre dealing with the adventures of the nine nathas. Phan ibhaua in Paratattvarasayanamu explains yoga in great detail. Vedantaviir t ikarn of Pararnanandayati mentions the navanathas and their activities and also quotes the one and a quarter lakh varieties of laya. Vaidyasaramu or Nava- natha Siddha Pr ad Ipika by Erlapap Perayya is said to have been written on the lines of the Siddhikriyas written by Navanatha siddh as. INTRODUCTlON : All the nathas or nat ha yogis are worshippers of siva and followers of sai visrn which is one of the oldest religious cults of India. -

Levels of Human Consciousness According to the Philosophy of Gorakhnath

Levels of Human Consciousness According to the Philosophy of Gorakhnath Gorakhnath was a Maha Yogi. He was not essentially a Philosopher in the commonly accepted meaning of the term. He did not seek for the absolute truth in the path of speculation and logical argumentation. He was not much interested in logically proving or disproving the existence of any ultimate noumenal reality beyond or behind immanent in the phenomenal world or our normal experience or intellectually ascertaining the nature of any such reality. He never made a display of his intellectual capacities as the upholder of any particular metaphysical theory in opposition to other rival theories. He knew that in the intellectual plane differences of views were inevitable especially with regard to the supreme truth which was beyond the realm of the normal intellect. Unbiased pursuit of truth in the path of philosophical reflection was according to him a very effective way to the progressive refinement of the intellect and its elevation to the higher and higher planes, leading gradually to the emancipation of consciousness from the bondage of all intellectual theories and sentimental attachments. Philosophical reflection (Tattva- Vicar) was therefore regarded as a valuable part of Yogic self discipline. Its principle aim should be make individual phenomenal consciousness free from all kinds of bias and prejudice, all forms of narrowness and bigotry all sorts of three conceived notions and emotional clinging in which its may be blessed with direct experience of the absolute truth by becoming perfectly united with it. With this object in view that Yogi Guru Gorakhnath taught what might be called a system of philosophy for guidance of the truth seekers in the path of intellectual self discipline.The name of Gorakhnath is famous for the authorship of good Sanskrit treatises is attributed to Gorakhnath himself. -

Biren Loses 3Rd Best CM Rank

www.ifp.co.in | RNI No 68899/96 VOL XVII/ISSUE 508 THURSDAY | OCTOBER 25 | 2018 POSTAL REGN NO. NE/MN 406 | PAGES 8 PRICE 3.60 First Lamka Bamboo Cleanliness drive Minister Shyamkumar fair inaugurated by MP for Manipur distributes winter Thangso Baite at YMA International Textile seeds to farmers Hall, Hmui Veng, Lamka Expo at Manipur under MIDH at Trade and Expo Khonghampat training Centre, Lamboi hall khongnangkong Biren loses 3rd best CM rank CM flags off second phase of MST bus CURRENCY service, introduces seven new routes at ISBT Dollar / Rupee: 73.15 Were the celebrations premature? Euro / Rupee: 83.38 By A Staff Reporter Jessami, Khoupum, Kamjong, will attend Ningol Chakkouba. Pound / Rupee: 94.44 who want him back in power.” Tamenglong, Tamei and Airport He said that public It may be mentioned that IMPHAL | Oct 23 Express (ISBT to Imphal transport service under the GOLD: 3,222 (1g/24K) when the sixth episode of the Chief minister N. Biren Airport) from Monday to aegis of MST was revived 3,012 (1g/22K) programme was covered, only flagged off the second Saturday. The Airport Express with an intention to solve the 23 states had been covered out phase of Manipur State will be available from airport inconvenience in travelling of 29 states and the remaining Transport (MST) passenger at 10 am, 12:15 am, 2 pm and faced by the people residing six states were still waiting for bus service after 16 months 4 pm and from ISBT at 9 am, in far-flung. The first phase of POLO assessment.