The Ever Growing Banyan Tree

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

REL 3337 Religions in Modern India Vasudha Narayanan

1 REL 3337 Religions in Modern India Vasudha Narayanan, Distinguished Professor, Religion [email protected] (Please use email for all communications) Office hours: Wednesdays 2:00-3:00 pm and by appointment Credits: 3 credit hours Course Term: Fall 2018 Class Meeting Time: M Period 9 (4:05 PM - 4:55 PM) AND 0134 W Period 8 - 9 (3:00 PM - 4:55 PM) In this course, you will learn about the religious and cultural diversity in the sub-continent, and understand the history of religion starting with the colonial period. We will study the major religious thinkers, many of whom had an impact on the political history of India. We will study the rites-of-passage, connections between food and religion, places of worship, festivals, gurus, as well as the close connections between religion and politics in many of these traditions. The religious traditions we will examine and intellectually engage with are primarily Hinduism, Jainism, Sikhism, as well as Christianity and Islam in India. We will strike a balance between a historical approach and a thematic one whereby sacraments, rituals, and other issues and activities that are religiously important for a Hindu family can be explained. This will include discussion of issues that may not be found in traditional texts, and I will supplement the readings with short journal and magazine articles, videos, and slides. The larger questions indirectly addressed in the course will include the following: Are the Indian concepts of "Hinduism" and western concepts of "religion" congruent? How ha colonial scholarship and assumptions shaped our understanding of South Asian Hindus and the "minority traditions" as distinct religious and social groups, blurring regional differences? How are gender issues made manifest in rituals? How does religious identity influence political and social behavior? How do Hindus in South Asia differentiate among themselves? Course Goals When you complete this course, you will be able to: 1. -

Particulars of Some Temples of Kerala Contents Particulars of Some

Particulars of some temples of Kerala Contents Particulars of some temples of Kerala .............................................. 1 Introduction ............................................................................................... 9 Temples of Kerala ................................................................................. 10 Temples of Kerala- an over view .................................................... 16 1. Achan Koil Dharma Sastha ...................................................... 23 2. Alathiyur Perumthiri(Hanuman) koil ................................. 24 3. Randu Moorthi temple of Alathur......................................... 27 4. Ambalappuzha Krishnan temple ........................................... 28 5. Amedha Saptha Mathruka Temple ....................................... 31 6. Ananteswar temple of Manjeswar ........................................ 35 7. Anchumana temple , Padivattam, Edapalli....................... 36 8. Aranmula Parthasarathy Temple ......................................... 38 9. Arathil Bhagawathi temple ..................................................... 41 10. Arpuda Narayana temple, Thirukodithaanam ................. 45 11. Aryankavu Dharma Sastha ...................................................... 47 12. Athingal Bhairavi temple ......................................................... 48 13. Attukkal BHagawathy Kshethram, Trivandrum ............. 50 14. Ayilur Akhileswaran (Shiva) and Sri Krishna temples ........................................................................................................... -

SACRED SPACES and OBJECTS: the VISUAL, MATERIAL, and TANGIBLE George Pati

SACRED SPACES AND OBJECTS: THE VISUAL, MATERIAL, AND TANGIBLE George Pati BRAUER MUSEUM OF ART | APRIL 13 — MAY 8, 2016 WE AT THE BRAUER MUSEUM are grateful for the opportunity to present this exhibition curated by George Pati, Ph.D., Surjit S. Patheja Chair in World Religions and Ethics and Valparaiso University associate professor of theology and international studies. Through this exhibition, Professor Pati shares the fruits of his research conducted during his recent sabbatical and in addition provides valuable insights into sacred objects, sites, and practices in India. Professor Pati’s photographs document specific places but also reflect a creative eye at work; as an artist, his documents are also celebrations of the particular spaces that inspire him and capture his imagination. Accompanying the images in the exhibition are beautiful textiles and objects of metalware that transform the gallery into its own sacred space, with respectful and reverent viewing becoming its own ritual that could lead to a fuller understanding of the concepts Pati brings to our attention. Professor Pati and the Brauer staff wish to thank the Surjit S. Patheja Chair in World Religions and Ethics and the Partners for the Brauer Museum of Art for support of this exhibition. In addition, we wish to thank Gretchen Buggeln and David Morgan for the insights and perspectives they provide in their responses to Pati's essay and photographs. Gregg Hertzlieb, Director/Curator Brauer Museum of Art 2 | BRAUER MUSEUM OF ART SACRED SPACES AND OBJECTS: THE VISUAL, MATERIAL, AND TANGIBLE George Pati George Pati, Ph.D., Valparaiso University Śvetāśvatara Upaniṣad 6:23 Only in a man who has utmost devotion for God, and who shows the same devotion for teacher as for God, These teachings by the noble one will be illuminating. -

Perhaps Do a Series and Take One Particular Subject at a Time

perhaps do a series and take one particular subject at a time. Sadhguru just as I was coming to see you I saw this little piece in one of the newspapers which said that one doesn’t know about India being a super power but when it comes to mysticism, the world looks to Indian gurus as the help button on the menu. You’ve been all over the world and spoken at many international events, what is your take on all the divine gurus traversing the globe these days? India as a culture has invested more time, energy and human resource toward the spiritual development of human beings for a very long time. This can only happen when there is a stable society for long periods without much strife. While all other societies were raked by various types of wars, and revolutions, India remained peaceful for long periods of time. So they invested that time in spiritual development, and it became the day to day ethos of every Indian. The world looking towards India for spiritual help is nothing new. It has always been so in terms of exploring the inner spaces of a human being-how a human being is made, what is his potential, where could he be taken in terms of his experiences. I don’t think any culture has looked into this with as much depth and variety as India has. Mark Twain visited India and after spending three months and visiting all the right places with his guide he paid India the ultimate compliment when he said that anything that can ever be done by man or God has been done in this land. -

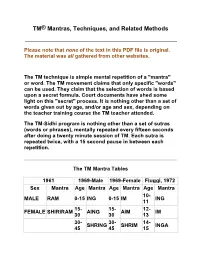

TM® Mantras, Techniques, and Related Methods

TM® Mantras, Techniques, and Related Methods Please note that none of the text in this PDF file is original. The material was all gathered from other websites. The TM technique is simple mental repetition of a "mantra" or word. The TM movement claims that only specific "words" can be used. They claim that the selection of words is based upon a secret formula. Court documents have shed some light on this "secret" process. It is nothing other than a set of words given out by age, and/or age and sex, depending on the teacher training course the TM teacher attended. The TM-Sidhi program is nothing other than a set of sutras (words or phrases), mentally repeated every fifteen seconds after doing a twenty minute session of TM. Each sutra is repeated twice, with a 15 second pause in between each repetition. The TM Mantra Tables 1961 1969-Male 1969-Female Fiuggi, 1972 Sex Mantra Age Mantra Age Mantra Age Mantra 10- MALE RAM 0-15 ING 0-15 IM ING 11 15- 15- 12- FEMALE SHIRIRAM AING AIM IM 30 30 13 30- 30- 14- SHRING SHRIM INGA 45 45 15 16- 46 + SHIAM 46 + SHIAMA IMA 17 18- AYING 19 20- AYIM 21 22- AYINGA 23 24- AYIMA 25 25 SHIRING October,19 1976 1977 1978 1987 78 Ag Ag Ag Ag Ag Mantra Mantra Mantra Mantra Mantra e e e e e 03- 03- 0- ENG ING ENG 10 10 11 10- 10- 10- 10- EM IN ENG ENG 12 12 12 12 12- 12- 12- 12- 12- ENGA INGA EM EM EM 14 14 14 14 13 14- 14- 14- 14- 14- EMA INA EMGA ENGA ENGA 16 16 16 16 15 16- 16- 16- 16- 16- AENG AING EMA EMA EMA 18 18 18 18 17 18- 18- 18- 18- 18- AEM AIM AENG AING AING 20 20 20 20 19 20- 20- 20- 20- 20- AENGA -

Superstition: a Rational Discourse

Superstition: A Rational Discourse Yadnyeshwar Nigale (Translated by Ms Suman Oak) Lokbhumi Prakashan Panaji (Goa) Credits Superstition: A Rational Discourse Author Yadnyeshwar Nigale (Translated by Ms Suman Oak) © Yadnyeshwar Nigale Articles may be reproduced freely acknowledging the source and a copy forwarded to Publisher. First Edition: June 2012 Layout & Production Milind Joshi, Anupam Creations, 2/14, Marwa, Anupam Park Kothrud, Pune 411029 Published & Printed by Ramesh Kolwalkar Lokbhumi Prakashan, Roshan Manzil, Near Cine National, Panaji (Goa) 403001 (Contact: 9763817239/(0832) 2251358) Cover Design Sham Bhalekar, Pune Rs : 150/- 2 Superstition: A Rational Discourse This book is respectfully dedicated to the memory of Comrade Narayan Desai (1920- 2007) a renowned thinker, philosopher & guide and wrote profusely and also was an activist in the progressive and rationalist movements Superstition: A Rational Discourse 3 The Author's Perception The Indian Society as a whole is beset with innumerable slovenly and unscientific concepts like-fatalism, fate or luck, the cycle of birth and death, Karmasiddhanta (present suffering or good fortune is the fruit of deeds in the previous births), astrology, destiny, miracles, concept of being auspicious or inauspicious, vows, observances and what not. To match with this innumerable orthodox senseless traditions and rituals are blindly followed by most of the Indians. In fact, the whole edifice of the Indian society and its culture is founded on these constructs. The psyche of the people does not allow them to examine any custom or tradition or happening and verify its utility, validity and legitimacy. For them, the age old customs, rituals and traditions, started by their wise forefathers are sacrosanct and beyond any criticism, leave alone any change. -

In the Hindu Temples of Kerala Gilles Tarabout

Spots of Wilderness. ’Nature’ in the Hindu Temples of Kerala Gilles Tarabout To cite this version: Gilles Tarabout. Spots of Wilderness. ’Nature’ in the Hindu Temples of Kerala. Rivista degli Studi Orientali, Fabrizio Serra editore, 2015, The Human Person and Nature in Classical and Modern India, eds. R. Torella & G. Milanetti, Supplemento n°2 alla Rivista Degli Studi Orientali, n.s., vol. LXXXVIII, pp.23-43. hal-01306640 HAL Id: hal-01306640 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01306640 Submitted on 25 Apr 2016 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Published in Supplemento n°2 alla Rivista Degli Studi Orientali, n.s., vol. LXXXVIII, 2015 (‘The Human Person and Nature in Classical and Modern India’, R. Torella & G. Milanetti, eds.), pp.23-43; in the publication the photos are in B & W. /p. 23/ Spots of Wilderness. ‘Nature’ in the Hindu Temples of Kerala Gilles Tarabout CNRS, Laboratoire d’Ethnologie et de Sociologie Comparative Many Hindu temples in Kerala are called ‘groves’ (kāvu), and encapsulate an effective grove – a small spot where shrubs and trees are said to grow ‘wildly’. There live numerous divine entities, serpent gods and other ambivalent deities or ghosts, subordinated to the presiding god/goddess of the temple installed in the main shrine. -

Glossary of Sanskrit and Pāli Terms

Glossary of Sanskrit and Pāli Terms Abhiniveśa Clinging to life, will-to-live, an urge for survival, or for self-preservation. Abhyāsa Practice. Ahaṁkāra The ego or self-referencing function of the mind, feelings, and thoughts about self at empirical level. Egoism or self-conceit; the self-arrogating principle “I” that is projected by the mind rather than the real self. Awareness of oneself, or of individuality. Ahiṁsā Nonviolence. Akliṣṭa Unhindered vṛttis (mental actions). Ālaya The subterraine stream of consciousness; self-existent consciousness con- ceived by the Vijñānavādins in Buddhism. Ānanda Bliss. Ānandamaya-kośa The “sheath of bliss”. Aṅga Limb or integral component of a system, such as in aṣṭāṅga (eight limbs) in Patañjali Yoga. Annamaya-kośa “The sheath of food (anna)”; the physical or gross body, nurtured by food; related to esoteric anatomy and physiology. Antaḥkaraṇa Literally means internal instrument, corresponding to what may be called the mind. Aparā Not transcendent; lower or limited; its opposite parā means supreme or superior. Placing an “a” before parā, makes it not superior or lower than. Parā can also mean far away (transcendent) so that aparā may mean empirical and immanent. Appanā The steady concentration leading to a state of absorption (Buddhist psychology). Arhant A high rank of self-realization lower than that of the Buddha. © Author(s) 2016 341 K. Ramakrishna Rao and A.C. Paranjpe, Psychology in the Indian Tradition, DOI 10.1007/978-81-322-2440-2 342 Glossary of Sanskrit and Pāli Terms Arūpaloka Formless world in Buddhism. Āsana Yogic physical posture, especially as recommended in Haṭha Yoga as one of the aids to concentration. -

K. Ramakrishna Rao ˇ Anand C. Paranjpe

K. Ramakrishna Rao · Anand C. Paranjpe Psychology in the Indian Tradition Psychology in the Indian Tradition K. Ramakrishna Rao • Anand C. Paranjpe Psychology in the Indian Tradition 123 K. Ramakrishna Rao Anand C. Paranjpe GITAM University Simon Fraser University Visakhapatnam, Andhra Pradesh Burnaby, BC India Canada The print edition of this book is not for sale in India, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, Nepal, Bhutan and Bangladesh. ISBN 978-81-322-2439-6 ISBN 978-81-322-2440-2 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-81-322-2440-2 Library of Congress Control Number: 2015937210 Springer New Delhi Heidelberg New York Dordrecht London © Author(s) 2016 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. The publisher, the authors and the editors are safe to assume that the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication. Neither the publisher nor the authors or the editors give a warranty, express or implied, with respect to the material contained herein or for any errors or omissions that may have been made. -

Date:/9/04/031 ORDER 1 .Vide Order No.05/G-Gaz.-IA/DHC/2021 Dated 29.01.2021, the Hon'ble High Court of Delhi Has Created Three New Labour Courts

GOVERNMENT OF NATIONAL CAPITAL TERRITORY OF DELHI LABOUT DEPARTMENT 5-SHAM NATH MARG, DELHI-110054 F.No.15(16)/Lab/2021//695- 1706 Date:/9/04/031 ORDER 1 .Vide order no.05/G-Gaz.-IA/DHC/2021 Dated 29.01.2021, the Hon'ble High Court of Delhi has created three new Labour Courts. The Labour Courts have been designated as under: S.No Labour COurt no. Ld. Presiding Officer Labour Court-01 2 Smt. Veena Rani Labour Court-02 Sh. Pawan Kumar Matto_ Labour Court-03 Sh. Raj kumar Labour Court-04 Sh Gorakh Nath Pandey Labour Court-05_ Sh. Sanatan Prasad Labour Court-06 Sh. Ramesh Kumar-II 7 Labour Court-07 Ms. Navita kumari Bagha 8 Labour Court-08 Sh. Tarun Yogesh 9 Labour Court-09 Sh. Joginder Prakash Nahar 2. Vide this office order no. F.No. 15(16)Lab/2021/647 dated 08.02.2021, the newly constituted Labour Courts have been transferred cases. All the district Joint Labour Commissioner/Deputy Labour Commissioner shall make reference of new Industrial Disputes to Labour Courts as per Table mentioned below District Area falling under following Police Stations Labour Court South Saket, Neb sarai , Hauz Khas . Malviya Nagar, Mehrauli , Fatehpur Beri, Labour Court No.l Lajpat Nagar, Amar colony. Defence Colony. Lodhi Colony, Hazrat Nizamuddin, Sriniwas Puri, Greater Kailash, Chitranjan Park, Kalkaji, Badarpur, Okhla Indl. Area, Ambedkar Nagar, Kotla Jamia Mubarakpur, Nagar, Sunlight Colony , Sangam vihar, Govind puri , Pul Prahlad puri, , Sarita vihar , Newfriends Colony, Jaitpur Labour Court No.2 South- Vasant Vihar, Vasant Kunj, Mahipalpur, RK. -

Why I Became a Hindu

Why I became a Hindu Parama Karuna Devi published by Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Copyright © 2018 Parama Karuna Devi All rights reserved Title ID: 8916295 ISBN-13: 978-1724611147 ISBN-10: 1724611143 published by: Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Website: www.jagannathavallabha.com Anyone wishing to submit questions, observations, objections or further information, useful in improving the contents of this book, is welcome to contact the author: E-mail: [email protected] phone: +91 (India) 94373 00906 Please note: direct contact data such as email and phone numbers may change due to events of force majeure, so please keep an eye on the updated information on the website. Table of contents Preface 7 My work 9 My experience 12 Why Hinduism is better 18 Fundamental teachings of Hinduism 21 A definition of Hinduism 29 The problem of castes 31 The importance of Bhakti 34 The need for a Guru 39 Can someone become a Hindu? 43 Historical examples 45 Hinduism in the world 52 Conversions in modern times 56 Individuals who embraced Hindu beliefs 61 Hindu revival 68 Dayananda Saraswati and Arya Samaj 73 Shraddhananda Swami 75 Sarla Bedi 75 Pandurang Shastri Athavale 75 Chattampi Swamikal 76 Narayana Guru 77 Navajyothi Sree Karunakara Guru 78 Swami Bhoomananda Tirtha 79 Ramakrishna Paramahamsa 79 Sarada Devi 80 Golap Ma 81 Rama Tirtha Swami 81 Niranjanananda Swami 81 Vireshwarananda Swami 82 Rudrananda Swami 82 Swahananda Swami 82 Narayanananda Swami 83 Vivekananda Swami and Ramakrishna Math 83 Sister Nivedita -

East Meets West

East Meets West The stories of the remarkable men and women from the East and the West who built a bridge across a cultural divide and introduced Meditation and Eastern Philosophy to the West John Adago SHEPHEARD-WALWYN (PUBLISHERS) LTD © John Adago 2014 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without the written permission of the publisher, Shepheard-Walwyn (Publishers) Ltd www.shepheard-walwyn.co.uk First published in 2014 by Shepheard-Walwyn (Publishers) Ltd 107 Parkway House, Sheen Lane, London SW14 8LS www.shepheard-walwyn.co.uk British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library ISBN: 978-0-85683-286-4 Typeset by Alacrity, Chesterfield, Sandford, Somerset Printed and bound in the United Kingdom by imprintdigital.com Contents Photographs viii Acknowledgements ix Introduction 1 1 Seekers of Truth 3 2 Gurdjieff in Russia 7 3 P.D. Ouspensky: The Work Comes to London 15 4 Willem A. Nyland: Firefly 27 5 Forty Days 31 6 Andrew MacLaren: Standing for Justice 36 7 Leon MacLaren: A School is Born 43 8 Adi Shankara 47 9 Shri Gurudeva – Swami Brahmananda Saraswati 51 10 Vedanta and Western Philosophy 57 11 Maharishi Mahesh Yogi: Flower Power – The Spirit of the Sixties 62 12 Swami Muktananda: Growing Roses in Concrete 70 13 Shantananda Saraswati 77 14 Dr Francis Roles: Return to the Source 81 15 Satsanga: Good Company 88 16 Joy Dillingham and Nicolai Rabeneck: Guarding the Light 95 17 Last Days 106 18 The Bridge 111 The Author 116 Appendix 1 – Words of the Wise 129 Appendix 2 – The Enneagram 140 Appendix 3 – Philosophy and Christianity 143 Notes 157 Bibliography 161 ~vii~ Photographs G.I.