University of Copenhagen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

P40 Layout 1

In Damascus, a ‘Cinema Paradiso’ struggles38 to stay open SUNDAY, SEPTEMBER 8, 2013 VENICE: Director Alexandros Avranas (C), actor Themis Panou and actress Eleni Roussinou pose on the red carpet as they arrive for the award ceremony of the 70th Venice Film Festival yesterday at Venice Lido. —AFP ritics have tipped movies from Britain, Japan and the inative tale of life in Japan between the two World Wars would A total of 20 films are competing at the festival, including not have the patience to appreciate my slowness,” he told jour- United States to win Venice’s Golden Lion prize this year, be his last feature. James Franco’s necrophilia flick “Child of God”, the tale of a social nalists. Some critics suggested that, with the US mulling inter- Cdue to be announced at the world’s oldest film festival “In the past, I have said many times I would quit. This time, it’s outcast whose loneliness drives him to live in a cave and murder vening in the Middle East again, the jury might give the award to yesterday. British director Stephen Frears provoked a hugely for real,” the 72-year-old said in Tokyo. He had become too old women to have sex with their bodies. Errol Morris’s “The Unknown Known”, an interview with former enthusiastic response with his charming tragi-comedy for the kind of craftsmanship and physical work required for US actor Scott Haze-who isolated himself for three months US defence secretary Donald Rumsfeld. “Philomena”, the true tale of a mother’s search for her son after major commercial projects, he added. -

Race and Transnationalism in the First Syrian-American Community, 1890-1930

Abstract Title of Thesis: RACE ACROSS BORDERS: RACE AND TRANSNATIONALISM IN THE FIRST SYRIAN-AMERICAN COMMUNITY, 1890-1930 Zeinab Emad Abrahim, Master of Arts, 2013 Thesis Directed By: Professor, Madeline Zilfi Department of History This research explores the transnational nature of the citizenship campaign amongst the first Syrian Americans, by analyzing the communication between Syrians in the United States with Syrians in the Middle East, primarily Jurji Zaydan, a Middle-Eastern anthropologist and literary figure. The goal is to demonstrate that while Syrian Americans negotiated their racial identity in the United States in order to attain the right to naturalize, they did so within a transnational framework. Placing the Syrian citizenship struggle in a larger context brings to light many issues regarding national and racial identity in both the United States and the Middle East during the turn of the twentieth century. RACE ACROSS BORDERS: RACE AND TRANSNATIONALISM IN THE FIRST SYRIAN-AMERICAN COMMUNITY, 1890-1930 by Zeinab Emad Abrahim Thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Maryland, College Park in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Arts 2013 Advisory Committee: Professor, Madeline Zilfi, Chair Professor, David Freund Professor, Peter Wien © Copyright by Zeinab Emad Abrahim 2013 For Mahmud, Emad, and Iman ii Table of Contents List of Images…………………………………………………………………....iv Introduction………………………………………………………………………1-12 Chapter 1: Historical Contextualization………………………………………13-25 -

Download Book

Arab American Literary Fictions, Cultures, and Politics American Literature Readings in the 21st Century Series Editor: Linda Wagner-Martin American Literature Readings in the 21st Century publishes works by contemporary critics that help shape critical opinion regarding literature of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries in the United States. Published by Palgrave Macmillan Freak Shows in Modern American Imagination: Constructing the Damaged Body from Willa Cather to Truman Capote By Thomas Fahy Arab American Literary Fictions, Cultures, and Politics By Steven Salaita Women and Race in Contemporary U.S. Writing: From Faulkner to Morrison By Kelly Lynch Reames Arab American Literary Fictions, Cultures, and Politics Steven Salaita ARAB AMERICAN LITERARY FICTIONS, CULTURES, AND POLITICS © Steven Salaita, 2007. Softcover reprint of the hardcover 1st edition 2007 978-1-4039-7620-8 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews. First published in 2007 by PALGRAVE MACMILLAN™ 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10010 and Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire, England RG21 6XS Companies and representatives throughout the world. PALGRAVE MACMILLAN is the global academic imprint of the Palgrave Macmillan division of St. Martin’s Press, LLC and of Palgrave Macmillan Ltd. Macmillan® is a registered trademark in the United States, United Kingdom and other countries. Palgrave is a registered trademark in the European Union and other countries. ISBN 978-1-349-53687-0 ISBN 978-0-230-60337-0 (eBook) DOI 10.1057/9780230603370 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available from the Library of Congress. -

The Prophet (Discussion Questions)

The Prophet (Discussion Questions) 1. Is Lebanese or Arab patriotism discernable? What is Gibran's view of America? Is there a political dimension to his work? 2. Can you identify with any of the characters? Does Gibran want you to identify with them? Do you think somebody in Lebanon would feel closer or less close to them? Why? 3. What is the prophet's message? What is his vision of human relationships in society? 4. How, overall, does Almustafa rate his ministry to Orphalese? 5. Can Gibran's writing be classified as immigration literature or are there more universal themes at work here? Could it just be romantic idealism? 6. How does Almitra figure in The Prophet? 7. How does Almustafa view nudity? 8. How does Almustafa relate to cities? 9. What is the function of human labor? 10. What is God's function in The Prophet? Is God a creator, provider, or savior, or does God serve some other function? 11. Does Almustafa's enigmatic promise to return through reincarnation fit in with his teachings on human nature? https://www.grpl.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/The-Prophet.pdf The Prophet (About the Author) Kahlil Gibran, known in Arabic as Gibran Khalil Gibran, was born January 6, 1883, in Bsharri, Lebanon, which at the time was part of Syria and part of the Ottoman Empire. In 1885 Gibran emigrated with his mother and siblings to the United States, where they settled in the large Syrian and Lebanese community in Boston, Massachusetts. In 1904 Gibran began publishing articles in an Arabic-language newspaper and also had his first public exhibit of his drawings, which were championed by the Boston photographer Fred Holland Day. -

Scholarship Resources for Minority Students

Welcome to Scholarship Resources for Diverse Populations! Compiled by Valerie Garr, [email protected] The University of Iowa, College of Nursing Diversity Office (Updated 7/31/13 VSG) IMPORTANT: This is an evolving list of potential scholarship resources for students who are one of or in combination of the following: minority, underrepresented, first generation, female, or undocumented, This list includes scholarship and financial aid resource information from sources predominantly not connected to the University of Iowa. Thus, unless noted, the University of Iowa does not determine award criteria, dollar amounts, application procedures, deadlines, or future renewal. This scholarship information may be helpful in assisting prospective and current students with their pursuit to finance a college education. The websites listed have been checked for authenticity but the UI is not responsible for the content, updating of, or access to any of these websites unless they are official UI links. It is recommended that you use this listing and the other information provided as a supplement to filing the FAFSA. Tips for Getting Scholarships and Other Financial Aid: • Work hard to get and maintain good grades in school • Perform as well as you can on your ACT, SAT, GRE etc… • Start early looking for scholarship money: internet, library, your community etc... • If a scholarship requires a letter of recommendation, ask your teacher/professor or counselor/advisor; someone who knows your academic ability in the classroom • If a scholarship requires you to write an essay, have a teacher/professor or counselor /advisor read your essay before you submit a final version; be prepared to re-write before final submission • Read the scholarship forms, applications, and deadlines carefully and follow instructions as indicated—Look for scholarships a YEAR In ADVANCE of your need! • File your FAFSA electronically as soon as possible after January 1st. -

A Main Document V202

ABSTRACT Title of dissertation: TELEVISION NEWS AND THE STATE IN LEBANON Jad P. Melki, Doctor of Philosophy, 2008 Dissertation directed by: Professor Susan D. Moeller College of Journalism This dissertation studies the relationship between television news and the state in Lebanon. It utilizes and reworks New Institutionalism theory by adding aspects of Mitchell’s state effect and other concepts devised from Carey and Foucault. The study starts with a macro-level analysis outlining the major cultural, economic and political factors that influenced the evolution of television news in that country. It then moves to a mezzo-level analysis of the institutional arrangements, routines and practices that dominated the news production process. Finally, it zooms in to a micro-level analysis of the final product of Lebanese broadcast news, focusing on the newscast, its rundown and scripts and the smaller elements that make up the television news story. The study concludes that the highly fragmented Lebanese society generated a similarly fragmented and deeply divided political/economic elite, which used its resources and access to the news media to solidify its status and, by doing so, recreated and confirmed the politico-sectarian divide in this country. In this vicious cycle, the institutionalized and instrumentalized television news played the role of mediator between the elites and their fragmented constituents, and simultaneously bolstered the political and economic power of the former while keeping the latter tightly held in their grip. The hard work and values of the individual journalist were systematically channeled through this powerful institutional mechanism and redirected to serve the top of the hierarchy. -

Exhibition Guide

A free exhibition presented at the State Library of New South Wales 4 December 2010 to 20 February 2011 Exhibition opening hours: 9 am to 8 pm Monday to Thursday, 9 am to 5 pm Friday, 10 am to 5pm weekends Macquarie Street Sydney NSW 2000 Telephone (02) 9273 1414 Facsimile (02) 9273 1255 TTY (02) 9273 1541 Email [email protected] www.sl.nsw.gov.au Curator: Avryl Whitnall The State Library of New South Wales is a statutory authority Exhibition project manager: Phil Verner of, and principally funded by, the NSW State Government Exhibition designers: Beth Steven and Stephen Ryan, The State Library acknowledges the generous support of the Freeman Ryan Design Nelson Meers Foundation Exhibition graphics: Nerida Orsatti, Freeman Ryan Design Print and marketing graphics: Marianne Hawke Names of people and works in this exhibition have been Editor: Theresa Willsteed westernised where appropriate for English-language publication. Unless otherwise stated, all works illustrated in this guide are Conservation services in Lebanon: David Butcher, by Kahlil Gibran (1883–1931), and are on loan from the Gibran Paris Art Consulting Museum, Bsharri, Lebanon. International freight: Terry Fahey, Global Specialised Services Printed in Australia by Pegasus Print Group Cover: Fred Holland Day, Kahlil Gibran with book, 1897, Paper: Focus Paper Evolve 275gsm (cover) and 120 gsm (text). photographic print, © National Media Museum/Science & Society The paper is 100% recycled from post-consumer waste. Picture Library, UK Print run: 10,000 Above: Fred Holland Day, Portrait of Kahlil Gibran, c. 1898, P&D-3499-11/2010 photographic print, © National Media Museum/Science & Society Picture Library, UK ISBN 0 7313 7205 0 © State Library of New South Wales, November 2010 FOREWORD Kahlil Gibran’s visit to the State Library of Kahlil Gibran had an enormous impact on many Gibran Khalil Gibran — writer, poet, artist From Bsharri to Sydney New South Wales is both timely and fitting. -

190 North Avenue

cover 11/3/03 2:37 PM Page 1 Winter 2003 Homecoming2003 preview 11/4/03 10:42 AM Page 3 3 Tech Topics Tech Vol. 40, No. 2 Winter 2003 gtalumni.org • Winter 2003 A Quick Read of Winter 2003 Contents Publisher: Joseph P. Irwin IM 80 Editor: John C. Dunn Associate Editor: Neil B. McGahee 08 True Grit 23 To the Point Assistant Editor: Maria M. Lameiras Assistant Editor: Kimberly Link-Wills Junior’s moved to smaller digs. Its next building was Herky Harris’ “giddyap” business style spurred his Design: Andrew Niesen & Rachel LaCour Niesen leveled by a wrecking ball. Through it all, this Tech career to the top and has proven invaluable to the institution has survived to “hold the dust.” Georgia Tech Foundation. Alumni Association Executive Committee 09 Planet of the Ape 25 Saving Lives, Saving Jobs L. Thomas Gay IM 66, president Robert L. Hall IM 64, past president Terry Maple, head of Georgia Alumnus David Rice’s manufac- Carey H. Brown IE 69, president elect/treasurer Tech’s new Center for turing business took a direct hit J. William Goodhew III IM 61, vice president activities Conservation and Behavior when a luggage company Janice N. Wittschiebe Arch 78, MS Arch 80, and former director of Zoo packed its bags and moved over- vice president Roll Call Atlanta, kicked off the seas. Not only did Rice’s compa- C. Meade Sutterfield EE 72, vice president communications Joseph P. Irwin IM 80, vice president and executive director Alumni Association’s ny survive the wound, it’s Homecoming events by shar- thriving as a maker of ing what he learned from bulletproof vests. -

2012-Fall.Pdf

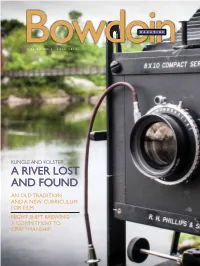

MAGAZINE BowdoiVOL.84 NO.1 FALL 2012 n KLINGLE AND KOLSTER A RIVER LOST AND FOUND AN OLD TRADITION AND A NEW CURRICULUM FOR FILM NIGHT SHIFT BREWING: A COMMITMENT TO CRAFTMANSHIP FALL 2012 BowdoinMAGAZINE CONTENTS 14 A River Lost and Found BY EDGAR ALLEN BEEM PHOTOGRAPHS BY BRIAN WEDGE ’97 AND MIKE KOLSTER Ed Beem talks to Professors Klingle and Kolster about their collaborative multimedia project telling the story of the Androscoggin River through photographs, oral histories, archival research, video, and creative writing. 24 Speaking the Language of Film "9,)3!7%3%,s0(/4/'2!0(3"9-)#(%,%34!0,%4/. An old tradition and a new curriculum combine to create an environment for film studies to flourish at Bowdoin. 32 Working the Night Shift "9)!.!,$2)#(s0(/4/'2!0(3"90!40)!3%#+) After careful research, many a long night brewing batches of beer, and with a last leap of faith, Rob Burns ’07, Michael Oxton ’07, and their business partner Mike O’Mara, have themselves a brewery. DEPARTMENTS Bookshelf 3 Class News 41 Mailbox 6 Weddings 78 Bowdoinsider 10 Obituaries 91 Alumnotes 40 Whispering Pines 124 [email protected] 1 |letter| Bowdoin FROM THE EDITOR MAGAZINE Happy Accidents Volume 84, Number 1 I live in Topsham, on the bank of the Androscoggin River. Our property is a Fall 2012 long and narrow lot that stretches from the road down the hill to our house, MAGAZINE STAFF then further down the hill, through a low area that often floods when the tide is Editor high, all the way to the water. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA, IRVINE the Arab Spring Abroad

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, IRVINE The Arab Spring Abroad: Mobilization among Syrian, Libyan, and Yemeni Diasporas in the U.S. and Great Britain DISSERTATION Submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in Sociology by Dana M. Moss Dissertation Committee: Distinguished Professor David A. Snow, Chair Chancellor’s Professor Charles Ragin Professor Judith Stepan-Norris Professor David S. Meyer Associate Professor Yang Su 2016 © 2016 Dana M. Moss DEDICATION To my husband William Picard, an exceptional partner and a true activist; and to my wonderfully supportive and loving parents, Nancy Watts and John Moss. Thank you for everything, always. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF ACRONYMS iv LIST OF FIGURES v LIST OF TABLES vi ACKNOWLEDGMENTS vii CURRICULUM VITAE viii ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION xiv INTRODUCTION 1 PART I: THE DYNAMICS OF DIASPORA MOVEMENT EMERGENCE CHAPTER 1: Diaspora Activism before the Arab Spring 30 CHAPTER 2: The Resurgence and Emergence of Transnational Diaspora Mobilization during the Arab Spring 70 PART II: THE ROLES OF THE DIASPORAS IN THE REVOLUTIONS 126 CHAPTER 3: The Libyan Case 132 CHAPTER 4: The Syrian Case 169 CHAPTER 5: The Yemeni Case 219 PART III: SHORT-TERM OUTCOMES OF THE ARAB SPRING CHAPTER 6: The Effects of Episodic Transnational Mobilization on Diaspora Politics 247 CHAPTER 7: Conclusion and Implications 270 REFERENCES 283 ENDNOTES 292 iii LIST OF ACRONYMS FSA Free Syria Army ISIS The Islamic State of Iraq and Al-Sham, or Daesh NFSL National Front for the Salvation -

Former Ottomans in the Ranks: Pro-Entente Military Recruitment Among Syrians in the Americas, 1916–18*

Journal of Global History (2016), 11,pp.88–112 © Cambridge University Press 2016 doi:10.1017/S1740022815000364 Former Ottomans in the ranks: pro-Entente military recruitment among Syrians in the Americas, 1916–18* Stacy D. Fahrenthold Center for Middle Eastern Studies, University of California, Berkeley, California, USA E-mail: [email protected] Abstract For half a million ‘Syrian’ Ottoman subjects living outside the empire, the First World War initiated a massive political rift with Istanbul. Beginning in 1916, Syrian and Lebanese emigrants from both North and South America sought to enlist, recruit, and conscript immigrant men into the militaries of the Entente. Employing press items, correspondence, and memoirs written by émigré recruiters during the war, this article reconstructs the transnational networks that facilitated the voluntary enlistment of an estimated 10,000 Syrian emigrants into the armies of the Entente, particularly the United States Army after 1917. As Ottoman nationals, many Syrian recruits used this as a practical means of obtaining American citizen- ship and shedding their legal ties to Istanbul. Émigré recruiters folded their military service into broader goals for ‘Syrian’ and ‘Lebanese’ national liberation under the auspices of American political support. Keywords First World War, Lebanon, mobilization, Syria, transnationalism Is it often said that the First World War was a time of unprecedented military mobilization. Between 1914 and 1918, empires around the world imposed powers of conscription on their -

Modern Arabic Literature Between the Nation and the World: the Bilingual Singularity of Kahlil Gibran

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Queen Mary Research Online 1 Modern Arabic Literature between the Nation and the World: The Bilingual Singularity of Kahlil Gibran Ghazouane Arslane Queen Mary University of London Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2019 2 I, Ghazouane Arslane, confirm that the research included within this thesis is my own work or that where it has been carried out in collaboration with, or supported by others, that this is duly acknowledged below and my contribution indicated. Previously published material is also acknowledged below. I attest that I have exercised reasonable care to ensure that the work is original, and does not to the best of my knowledge break any UK law, infringe any third party’s copyright or other Intellectual Property Right, or contain any confidential material. I accept that the College has the right to use plagiarism detection software to check the electronic version of the thesis. I confirm that this thesis has not been previously submitted for the award of a degree by this or any other university. The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without the prior written consent of the author. Signature: Ghazouane Arslane Date: 23/12/2019 3 Table of Contents Abstract ............................................................................................................................ 4 Note on Translation,