Fragmented Bodies, Legal Privilege, and Commodification in Science and Medicine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Biotechnology and Society Syllabus

Nanyang Technological University Humanities and Social Sciences Semester 1, AY2017-2018 HH3010 Biotechnology and Society Syllabus Subject Description This subject will introduce students to selected research and commercial applications of modern biotechnology in order to discuss the broader social, ethical, risk, and regulatory issues that arise from them. A range of topics will be covered in this subject, including genetic engineering, cloning, stem cell research, the production of pharmaceuticals, the human genome project, genetic testing, assisted reproductive technologies, and synthetic biology. Students will consider debates that have taken place in the wider community about ownership, commercialisation, identity, governance, animal welfare, human well-being, and expertise in relation to these applications of modern biotechnology. Prerequisites: Nil Academic Units: 3 Teaching Staff Hallam Stevens Office: HSS-05-07 Email: [email protected] Attendance Requirements Students are expected to attend one two hour lecture and one one-hour tutorial once per week: Lectures: Wednesdays 12.30-2.30pm (LHS Lecture Theatre) Tutorials: Wednesdays 3.30pm-4.30pm OR 4.30pm-5.30pm OR 5.30-6.30pm (LHS TR+45) Tutorials begin in Week 2 and run through to Week 13 (except for weeks 7 and 9). You are required to attend at least eight of these tutorials. If you attend fewer than 8 tutorials you will get zero for your participation and discussion grade 1 (20% of your overall grade). This includes any excused absences (eg. medical reasons still count as “missed” tutorials). Medical certificates are not a get out of jail free card. Missing a seminar without an MC will mean an automatic zero for any attendance and participation marks awarded for that week. -

Edinburgh Research Explorer

Edinburgh Research Explorer Genetically engineering milk Citation for published version: Whitelaw, CBA, Joshi, A, Kumar, S, Lillico, SG & Proudfoot, C 2016, 'Genetically engineering milk', Journal of Dairy Research, vol. 83, no. 1, pp. 3-11. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022029916000017 Digital Object Identifier (DOI): 10.1017/S0022029916000017 Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Peer reviewed version Published In: Journal of Dairy Research General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 25. Sep. 2021 Short title: Genetically engineering milk Genetically engineering milk C. Bruce A. Whitelaw1,*, Akshay Joshi1, Satish Kumar2, Simon G. Lillico1 and Chris Proudfoot1. The Roslin Institute and Royal (Dick) School of Veterinary Sciences, University of Edinburgh, Easter Bush CamPus, Midlothian EH25 9RG, UK1 Centre for Cellular and Molecular Biology, Hyderabad, India2 * For correspondence: [email protected] Received 22nd December 2015 and accepted for Publication 1st January 2016 It has been thirty years since the first genetically engineered animal with altered milk composition was rePorted. -

Cloning in Farm Animals: Concepts and Applications

Biochemistry and Biotechnology Research Vol. 3(1), pp. 1-10, February 2015 ISSN: 2354-2136 Review Cloning in farm animals: Concepts and applications Anwar Shifaw1 and Mebratu Asaye2* 1College of Veterinary Medicine and Agriculture, Addis Ababa University, P.O. Box 34, Debre Zeit, Ethiopia. 2Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, University of Gondar, P. O. Box 196, Gondar, Ethiopia. Accepted 9 February, 2015 ABSTRACT Cloning is a scientific term used to describe the process of genetic duplication. The most commonly applied and recent technique is nuclear transfer from somatic cell, in which the nucleus from a body cell transferred to an egg cell to create an embryo that is virtually genetically identical to the donor nucleus. Cloning has started early in the development of biological science during the Theodor Schwann period of cell theory. The application of animal cloning are rapid multiplication of desired livestock, animal preservation, research models, human cell based therapies, xenotransplantation and gene farming. However, cloning of animals is restricted to highly advanced laboratories in developed countries. The problems associated with farm animal cloning has been reviewed and discussed in this paper which includes incomplete reprogramming, placental abnormalities, parturition difficulties, postnatal death, clone specific phenotype and lung emphysema as well as socio-cultural problems. Most of the problems were molecularly explained as the failure of genetic reprogramming. In Ethiopia this type of science is not yet conceived and -

Human Embryonic Stem Cells and Clinical Applications

Cell Research (2008) 18:s171. npg © 2008 IBCB, SIBS, CAS All rights reserved 1001-0602/08 $ 30.00 Plenary Session 5 www.nature.com/cr Human embryonic stem cells and clinical applications Alan Colman1 1 Executive Director, Singapore Stem Cell Consortium, A*STAR Institute of Medical Biology, Singapore With the 2007 Nobel prize awards to Evans, Capecchi and Smithers, embryonic stem cell research has been rightly recognized for its enormous contributions towards increasing our understanding of mammalian development and disease. Much of this insight has arisen from the provision of mice knock out models. However, observations that the embryonic stem cell can be coaxed into a multitude of different cell types in vitro have also captured enormous attention. This matchless versatility is now being intensively exploited in human embryonic stem cells (hESC) with a view to providing partial or complete cures for a vast legion of troubling human ailments. Whilst the pluripotential nature of hESC offers the advantage, in principle, of allowing a wide choice of disease targets, the early developmental status of the cells makes efficient and correct differentiation into the desired adult cell types a difficult undertaking. In my lecture, I will explore the challenges and progress that accompany the translational efforts being made with hESC. In particular, I will survey progress towards clinical applications in the diabetes, congestive heart failure and spinal injury indications, paying attention to outstanding regulatory issues like safety and GMP compliance in this very difficult area of cell therapy. I will conclude that technical difficulties together with regulatory and investment concerns, are likely to impede clinical development of hESC cell therapy. -

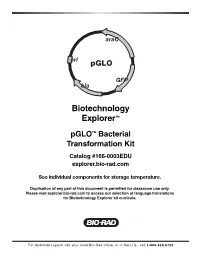

Biotechnology Explorer™

araC ori pGLO GFP bla Biotechnology Explorer™ pGLO™ Bacterial Transformation Kit Catalog #166-0003EDU explorer.bio-rad.com See individual components for storage temperature. Duplication of any part of this document is permitted for classroom use only. Please visit explorer.bio-rad.com to access our selection of language translations for Biotechnology Explorer kit curricula. For technical support call your local Bio-Rad office, or in the U.S., call 1-800-424-6723 How can jellyfish shed light on the subject? One of the biggest challenges for first-time students of biotechnology or molecular biology is that many of the events and processes they are studying are invisible. The Biotechnology Explorer program has a solution: a gene from a bioluminescent jellyfish and its Green Fluorescent Protein—GFP. GFP fluoresces a brilliant green when viewed with a hand-held long-wave ultraviolet light (such as a pocket geology lamp). The gene for GFP was originally isolated from the jellyfish, Aequorea victoria. The wild-type jellyfish gene has been modified by Maxygen Inc., a biotechnology company in Santa Clara, California. Specific mutations were introduced into the DNA sequence, which greatly enhance fluorescence of the protein. This modified form of the GFP gene has been inserted into Bio-Rad’s pGLO plasmid and is now available exclusively from Bio-Rad for educational applications. GFP is incredibly bright. Using pGLO to transform bac teria, students can actually observe gene expression in real time. Following the transformation with Bio-Rad’s GFP purification kit, students purify the genetically engineered GFP from their transformed bacteria using a simple chromatography procedure. -

Pharmaceuticals, Biologics and Biopharmaceuticals

BIOPHARMACEUTICALS BIOCHEMISTRY AND BIOTECHNOLOGY Second Edition Gary Walsh Industrial Biochemistry Programme CES Department University of Limerick, Ireland BIOPHARMACEUTICALS BIOCHEMISTRY AND BIOTECHNOLOGY Second Edition BIOPHARMACEUTICALS BIOCHEMISTRY AND BIOTECHNOLOGY Second Edition Gary Walsh Industrial Biochemistry Programme CES Department University of Limerick, Ireland First Edition 1998 u John Wiley & Sons, Ltd Copyright u 2003 John Wiley & Sons Ltd, The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex PO19 8SQ, England Telephone (+44) 1243 779777 E-mail (for orders and customer service enquiries): [email protected] Visit our Home Page on www.wileyeurope.com or www.wiley.com All Rights Reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning or otherwise, except under the terms of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 or under the terms of a licence issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency Ltd, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London W1T 4LP, UK, without the permission in writing of the Publisher. Requests to the Publisher should be addressed to the Permissions Department, John Wiley & Sons Ltd, The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex PO19 8SQ, England, or emailed to [email protected], or faxed to (+44) 1243 770620. This publication is designed to provide accurate and authoritative information in regard to the subject matter covered. It is sold on the understanding that the Publisher is not engaged in rendering professional services. If professional advice or other expert assistance is required, the services of a competent professional should be sought. Other Wiley Editorial Offices John Wiley & Sons Inc., 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030, USA Jossey-Bass, 989 Market Street, San Francisco, CA 94103-1741, USA Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH, Boschstr. -

Dolly: the Science Behind the World's Most Famous Sheep

DOLLY: THE SCIENCE BEHIND THE WORLD’S MOST FAMOUS SHEEP H.D. Griffin Roslin Institute (Edinburgh), Roslin, UK Abstract ‘The Roslin Institute near Edinburgh is one of the world’s leading centres for research on farm animals. Its main expertise is in animal genetics, with the results benefiting the livestock breeding and production industries in particular. Its work was, however, little known to the general public. A single lamb changed all that. Dr Harry Griffin, Assistant Director at the Institute, explains.....’ Dolly was the first mammal cloned from a cell from an adult animal. She was derived from cells that had been taken from the udder of a 6-year old Finn Dorset ewe and cultured for several weeks in the laboratory. Individual cells were then fused with unfertilised eggs from which the genetic material had been removed. Two hundred and seventy seven of these ‘reconstructed eggs’ - each now with a diploid nucleus from the adult animal - were cultured for 6 days in temporary recipients. Twenty nine of the eggs that appeared to have developed normally to the blastocyst stage were implanted into surrogate Scottish Blackface ewes. One gave rise to live lamb, Dolly, some 148 days later. DOLLYMANIA Dolly was born on 5 July 1996. It took Ian Wilmut and his colleagues a few weeks to complete the experimental work and several more months before they had written a paper and had it accepted by Nature. Publication was confirmed for 27 February, 1997 and by then plans were well advanced to handle the expected media interest. We knew that Nature was featuring Dolly in the weekly press release that it distributes each Friday. -

Sunita Grover V. K. Batish V. Padmanabha Reddy Dairy Biotechnology

Sunita Grover V. K. Batish V. Padmanabha Reddy Dairy Biotechnology Sunita Grover & V. K. Batish Dairy Microbiology Division NDRI, Karnal V. Padmanabha Reddy Dairy Microbiology Division SVVU, Tirupati Index Modules Page No Module 1. Introduction to Biotechnology Lesson 1. Definition and Scope of Biotechnology 5-6 Lesson 2. Historical development (Time line) of Biotechnology 7-15 Lesson 3. Future applications of Biotechnology 16-21 Module 2. Fundamental Biological Principles Lesson 4. Nucleic acids – Structure and function of DNA and 22-29 RNA Lesson 5. DNA replication and Genetic Code 30-34 Lesson 6. Gene expression – Transcription and Translation 35-41 Lesson 7. Gene regulation - The 'Lac operon' 42-47 Lesson 8. Mutations 48-59 Module 3. Genetic Engineering Technology/Recombinant DNA Technology Lesson 9. Molecular cloning - Tools 60-65 Lesson 10. Restriction enzymes 66-74 Lesson 11. Vectors 75-83 Lesson 12. Introduction of recombinant DNA into host cell 84-90 Lesson 13. DNA sequencing 91-95 Lesson 14. PCR and Real Time PCR 96-107 Lesson 15. DNA Microarray 108-112 Module 4. Cell Culture and Fusion Technology Lesson 16. Animal Cell Culture 113-119 Lesson 17. Protoplast/ Somatic fusion and Hybridoma 120-124 technology Lesson 18. Stem Cells and Nuclear cloning 125-134 Module 5. Application of Biotechnology in Dairying Lesson 19. Application of Genetic Engineering in dairy starter 135-140 cultures Lesson 20. Accelerated Cheese Ripening 141-146 Lesson 21. Dairy enzymes and whole cell immobilization 147-155 Lesson 22. Cloning and expression of genes in bacteria and 156-164 yeast Lesson 23. Large scale production and downstream processing 165-176 of recombinant proteins Lesson 24. -

From Reproductive Technologies to Genome Editing in Small Ruminants: an Embryo’S Journey

DOI: 10.21451/1984-3143-AR2018-0022 Proceedings of the 10th International Ruminant Reproduction Symposium (IRRS 2018); Foz do Iguaçu, PR, Brazil, September 16th to 20th, 2018. From reproductive technologies to genome editing in small ruminants: an embryo’s journey Alejo Menchaca1,*, Pedro C. dos Santos-Neto1, Frederico Cuadro1, Marcela Souza-Neves1, Martina Crispo2 1Instituto de Reproducción Animal Uruguay (IRAUy), Montevideo, Uruguay. 2Unidad de Animales Transgénicos y de Experimentación, Institut Pasteur de Montevideo, Uruguay. Abstract Follicular dynamics in sheep and goats The beginning of this century has witnessed Since a deep knowledge of ovarian physiology great advances in the understanding of ovarian is required for the control of reproduction and the physiology and embryo development, in the application of assisted reproductive technologies improvement of assisted reproductive technologies (ARTs; Fig. 1), a brief update of ovarian follicular (ARTs), and in the arrival of the revolutionary genome dynamics is presented. The follicular wave pattern in editing technology through zygote manipulation. sheep and goats was clearly described in the 1990s with Particularly in sheep and goats, the current knowledge the advent of transrectal ultrasonography for the study on follicular dynamics enables the design of novel of ovarian physiology (reviewed in sheep by Evans, strategies for ovarian control, enhancing artificial 2003, and in goats by Rubianes and Menchaca, 2003). insemination and embryo production programs applied Follicular waves in these species have been reported to genetic improvement. In vitro embryo production during the estrous cycle, prepubertal period, seasonal (IVEP) has evolved due to a better understanding of the anestrus and early gestation. This phenomenon is processes that occur during oocyte maturation, determined by the precise action of the endocrine fertilization and early embryo development. -

Biotechnology & Its Applications

Biotechnology & its Applications Recombinant DNA technology Definition: Genetic engineering, a kind of biotechnology, is the latest branch in applied genetics dealing the alteration of the genetic makeup of cells by deliberate and artificial means. Genetic engineering involves transfer or replacement of genes, so also known as recombination DNA technology or gene splicing. Tools of genetic engineering: (1) Two enzymes used in genetic engineering are restriction endonuclease and ligases. (2) R.E. is used to cut the plasmid as well as the foreign DNA molecules of specific points while ligase is used to seal gaps or to join bits of DNA. (3) The ability to clone and sequence essentially any gene or other DNA sequence of interest from any species depends on a special class of enzymes called restriction endonucleases. (4) Restriction endonucleases are also called as molecular scissors or ‘chemical scalpels’. (5) Restriction endonucleases cleave DNA molecules only at specific nucleotide sequence called restriction sites. (6) The first restriction enzyme identified from a bacterial strain is designated I, the second II and so on, thus, restriction endonuclease EcoRI is produced by Escherichia coli strain RY 13. (7) Restriction enzyme called EcoRI recognizes the sequence 473 (8) It then cleaves the DNA between G and A on both strands. Restriction nucleases make staggered cuts; that is, they cleave the two strands of a double helix at different joints and blunt ended fragments; that is, they cut both strands at same place. Steps of recombinant DNA technology (1) Isolating a useful DNA segment from the donor organism. (2) Splicing it into a suitable vector under conditions to ensure that each vector receives no more than one DNA fragment. -

BUREAU's Class-XII

BUREAU’S HIGHER SECONDARY Class-XII Prescribed by Council of Higher Secondary Education, Odisha, Bhubaneswar BOARD OF WRITERS Dr. Manoranjan Kar Dr. Manas Ranjan Satapathy Formerly Professor in Botany, Lecturer in Botany, Utkal Univeristy, Vani Vihar, Bhubaneswar Dhenkanal (Autonomous) College, Dhenkanal Dr. Baman Chandra Acharya Dr. Subas Chandra Das Formerly Professor in Botany, Formerly Principal, Khalikote (Autonomous) College, Berhampur Sundergarh Women's College, Sundergarh Dr. Basanta Kumar Choudhury Dr. Pradeep Kumar Mohanty Formerly Reader in Botany, Presently, Editor, 'Bigyan Associate Professor in Zoology, Diganta', Odisha Bigyan Academy, Bhubaneswar Dhenkanal (Autonomous) College, Dhenkanal Dr. Ajay Kumar Acharya Dr. Jaya Krushna Panigrahi Reader in Botany, Swami Vivekananda Memorial Reader in Zoology, Sri Jayadev College of Education & (Autonomous) College, Jagatsinghpur Technology, Bhubaneswar Shri Uday Shankar Acharya Dr. Bairagi Charan Behera Associate Professor in Botany, Reader in Zoology, Samanta Chandra Sekhar (Autonomous) College, Puri Kendrapara (Autonomous) College, Kendrapara Dr. Hrushikesh Nayak Dr. Maheswar Behera Lecturer in Botany, Associate Professor in Zoology, Bhadrak (Autonomous) College, Bhadrak Samanta Chandra Sekhar (Autonomous) College, Puri BOARD OF REVIWERS Dr. Manoranjan Kar Dr. Basanta Kumar Choudhury Formerly Professor in Botany Formerly Reader in Botany, Presently, Editor, 'Bigyan Utkal Univeristy, Vani Vihar, Bhubaneswar Diganta', Odisha Bigyan Academy, Bhubaneswar Dr. Baman Chandra Acharya Dr. Subas Chandra Das Formerly Professor in Botany Formerly Principal, Khalikote (Autonomous) College, Berhampur Sundergarh Women's College, Sundergarh Dr. Pradeep Kumar Mohanty Associate Professor in Zoology Dhenkanal (Autonomous) College, Dhenkanal ODISHA STATE BUREAU OF TEXTBOOK PREPARATION AND PRODUCTION Pustak Bhavan, Bhubaneswar Published by : THE ODISHA STATE BUREAU OF TEXTBOOK PREPARATION AND PRODUCTION Pustak Bhavan, Bhubaneswar, Odisha, India First Edition : 2017 / 5000 Publication No. -

Keith Henry Stockman Campbell, Phd

CSIRO PUBLISHING Reproduction, Fertility and Development, 2015, 27, xxvi–xxviii http://dx.doi.org/10.1071/RDv27n1_PA2 Recipient of the 2015 IETS Pioneer Award: Keith Henry Stockman Campbell, PhD Dr Keith Henry Stockman Campbell was born in Birmingham, England, to an English mother and Scottish father. He started his education in Perth, Scotland, but when he was 8 years old, his family returned to Birmingham. He was educated at King Edward VI Grammar School for boys and then trained and became qualified as a medical laboratory technologist specia- lising in medical microbiology at Selly Oak Hospital. At age 21, Keith attended Queen Elizabeth College, London, where he obtained a BSc in microbiology in 1983. During these studies, he became interested in the cell cycle and cellular growth. Following brief positions, first as chief medical laboratory technologist in Southern Yemen and then on a program to eradicate Dutch elm disease in parts of Southern England, he joined the cytogenetics group of Dr Bishun at the Marie Curie Institute. At the Curie Foundation, Keith’s interests in the regulation of cellular growth, particularly differentiation, increased. In 1983, he was awarded the Marie Curie Research Scholarship and moved to the University of Sussex as a post- graduate student where he studied the cytoplasmic control of nuclear behaviour during the development of amphibian eggs, early embryos, and during cell growth and division in yeast. nuclear donors. With this notion he shocked the world by Keith was particularly interested in the ubiquitous nature of successfully cloning a sheep from adult mammary cells. such cytoplasmic factors in eukaryotic cell types.