Dolly at Roslin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CURRICULUM VITAE Marijo G

CURRICULUM VITAE Marijo G. Kent–First, B.A, M.S, Ph.D. CURRENT CORRESPONDING ADDRESS: BIRTH PLACE Bainbridge, GA, USA 3832 McFarlane Drive Tallahassee, FL 32303 Phone: NATIONALITY American/USA *Cell: 662-341-5243 (cell) E-mail: [email protected] Email: [email protected]+ PERSONAL and PROFESSIONAL INTERESTS: -Training of students in Basic Sciences, Anatomy, Physiology and Genetics, Veterinary and Human Medicine and Pharmacy -Maintain animals carrying rare genetic mutation(s) for use in undergraduate research projects. -Research Focus: Reproductive genetics; embryogenesis/ oxidative stress induced genomic instability and tumorigenesis - Commercial Focus: Development of novel assays and tools for cancer diagnostics. - Breed, train & show horses across multiple disciplines Philosophy: Excellence in teaching and research is best achieved through active student/mentor relationships! “The most inspirational pioneers in science are often described as being passionate about their work with a little bit of eccentricity thrown in for good measure --- Science is fun and the process of learning should be an exciting adventure for both professor and student”! EDUCATION/DEGREES/CERTIFICATIONS POST-DOCTORAL: 2014-present Certification for Online Education and Teaching at Jackson State University Jackson State University Jackson, MS. (Ms. Tamika Morehead) 1990 - 1991 Reproductive Genetics Consultant- Clinical Embryology Bourn Hall Infertility Clinic, Bourn, Cambridge, UK (Prof. R.G. Edwards) Preimplantation Genetic Diagnosis and sex selection in human embryos resulting from in vitro fertilization (IVF) 1988 - 1990 Genetic Consultant - American Breeders Service Deforest, WI (Dr. R. Walton and Dr. J. Sullivan) Preimplantation Genetic Diagnosis; Sex selection in bovine 1988 -1990 Associate Scientist -University of WI, Madison Dept. of Meat and Animal Science (Prof. -

The Effect of Interspecific Oocytes on Demethylation of Sperm DNA

The effect of interspecific oocytes on demethylation of sperm DNA Nathalie Beaujean*†‡, Jane E. Taylor*, Michelle McGarry*, John O. Gardner*, Ian Wilmut*, Pasqualino Loi§, Grazyna Ptak§, Cesare Galli¶, Giovanna Lazzari¶, Adrian Birdʈ, Lorraine E. Young**††, and Richard R. Meehan†‡‡ *Division of Gene Expression and Development, Roslin Institute, Roslin EH25 9PS, United Kingdom; †Department of Biomedical and Clinical Laboratory Sciences, University of Edinburgh, Hugh Robson Building, George Square, Edinburgh EH8 9XD, United Kingdom; §Department of Comparative Biomedical Sciences, Teramo University, Teramo 64100, Italy; ¶Laboratorio di Tecnologie della Riproduzione, Istituto Sperimentale Italiano Lazzaro Spallanzani, CIZ srl, Via Porcellasco 7͞f, 26100 Cremona, Italy; ʈWellcome Trust Centre for Cell Biology, University of Edinburgh, The King’s Buildings, Edinburgh EH9 3JR, United Kingdom; **Institute of Genetics and Division of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, University of Nottingham, Queens Medical Centre, Nottingham NG7 2UH, United Kingdom; and ‡‡Human Genome Unit, Medical Research Council, Western General Hospital, Crewe Road, Edinburgh EH4 9XU, United Kingdom Edited by Rudolf Jaenisch, Whitehead Institute for Biomedical Research, Cambridge, MA, and approved April 7, 2004 (received for review February 2, 2004) In contrast to mice, in sheep no genome-wide demethylation of the Materials and Methods paternal genome occurs within the first postfertilization cell cycle. All animal procedures were under strict accordance with U.K. This difference could be due either to an absence of a sheep Home Office regulations and within a project license issued demethylase activity that is present in mouse ooplasm or to an under the Animal (Scientific Procedures) Act of 1986. increased protection of methylated cytosine residues in sheep sperm. -

Dolly the Sheep – the First Cloned Adult Animal

DOLLY THE SHEEP – THE FIRST CLONED ADULT ANIMAL NEW TECHNOLOGY FOR IMPROVING LIVESTOCK From Squidonius via Wikimedia Commons In 1996, University of Edinburgh scientists celebrated the birth of Dolly the Sheep, the first mammal to be cloned using SCNT cloning is the only technology adult somatic cells. The Edinburgh team’s success followed available that enables generation of 99.8% its improvements to the single cell nuclear transfer (SCNT) genetically identical offspring from selected technique used in the cloning process. individuals of adult animals (including sterilized animals). As such, it is being Dolly became a scientific icon recognised worldwide and exploited as an efficient multiplication tool SCNT technology has spread around the world and has been to support specific breeding strategies of used to clone multiple farm animals. farm animals with exceptionally high genetic The cloning of livestock enables growing large quantities of value. the most productive, disease resistant animals, thus providing more food and other animal products. Sir Ian Wilmut (Inaugural Director of MRC Centre for Regeneration and Professor at CMVM, UoE) and colleagues worked on methods to create genetically improved livestock by manipulation of stem cells using nuclear transfer. Their research optimised interactions between the donor nucleus and the recipient cytoplasm at the time of fusion and during the first cell cycle. Nuclear donor cells were held in mitosis before being released and used as they were expected to be passing through G1 phase. CLONING IN COMMERCE, CONSERVATION OF AGRICULTURE AND PRESERVATION ANIMAL BREEDS OF LIVESTOCK DIVERSITY Cloning has been used to conserve several animal breeds in the recent past. -

The Mendel Newsletter

THE MENDEL NEWSLETTER Archival Resources for the History of Genetics & Allied Sciences ISSUED BY THE LIBRARY OF THE AMERICAN PHILOSOPHICAL SOCIETY New Series, No. 20 June 2015 IN THIS ISSUE John Marius Opitz Papers at the American Philosophical Society — Charles Greifenstein 3 Animal Genetics Collections at Edinburgh University Library Special Collections — Clare Button 6 Rethinking Russian Studies on the Genetics of Natural Populations: Vassily Babkoff’s Papers and the History of the “Evolutionary Brigade,” 1934–1940 — Kirill Rossiianov and Tatiana Avrutskaya 15 Centrum Mendelianum: The Mendel Museum Moved to the Former Premises of Mendel’s Scientific Society — Anna Matalová and Eva Matalová 25 Resident Research Fellowships in Genetics, History of Medicine and Related Disciplines 36 THE AMERICAN PHILOSOPHICAL SOCIETY LIBRARY Philadelphia The Mendel Newsletter June 2015 The Mendel Newsletter American Philosophical Society Library 105 South Fifth Street Philadelphia PA 19106-3386 U.S.A. www.amphilsoc.org/library Editor Managing Editor Michael Dietrich Earle E. Spamer, American Philosophical Society Department of Biological Sciences [email protected] 215 Gilman Hall, HB 6044 Dartmouth College Hanover NH 03755 The Mendel Newsletter [email protected] [email protected] Editorial Board Mark B. Adams, University of Pennsylvania Barbara Kimmelman, Philadelphia University Garland E. Allen, Washington University Martin L. Levitt, American Philosophical Society John Beatty, University of Minnesota Jane Maienschein, Arizona State University Frederick B. Churchill, Indiana University Diane B. Paul, University of Massachusetts, Boston Michael R. Dietrich, Dartmouth College Jan Sapp, York University,Toronto Bernardino Fantini, Institut Louis Jantet d’Histoire Vassiliki Beatty Smocovitis, University of Florida de Medicine, Geneva The Mendel Newsletter, New Series, No. -

Biotechnology and Society Syllabus

Nanyang Technological University Humanities and Social Sciences Semester 1, AY2017-2018 HH3010 Biotechnology and Society Syllabus Subject Description This subject will introduce students to selected research and commercial applications of modern biotechnology in order to discuss the broader social, ethical, risk, and regulatory issues that arise from them. A range of topics will be covered in this subject, including genetic engineering, cloning, stem cell research, the production of pharmaceuticals, the human genome project, genetic testing, assisted reproductive technologies, and synthetic biology. Students will consider debates that have taken place in the wider community about ownership, commercialisation, identity, governance, animal welfare, human well-being, and expertise in relation to these applications of modern biotechnology. Prerequisites: Nil Academic Units: 3 Teaching Staff Hallam Stevens Office: HSS-05-07 Email: [email protected] Attendance Requirements Students are expected to attend one two hour lecture and one one-hour tutorial once per week: Lectures: Wednesdays 12.30-2.30pm (LHS Lecture Theatre) Tutorials: Wednesdays 3.30pm-4.30pm OR 4.30pm-5.30pm OR 5.30-6.30pm (LHS TR+45) Tutorials begin in Week 2 and run through to Week 13 (except for weeks 7 and 9). You are required to attend at least eight of these tutorials. If you attend fewer than 8 tutorials you will get zero for your participation and discussion grade 1 (20% of your overall grade). This includes any excused absences (eg. medical reasons still count as “missed” tutorials). Medical certificates are not a get out of jail free card. Missing a seminar without an MC will mean an automatic zero for any attendance and participation marks awarded for that week. -

Edit Summer 2007

60282_Edit_Summer07 2/5/07 02:01 Page 1 The University of Edinburgh INCLUDING BILLET & GENERAL COUNCIL PAPERS SUMMER 07 Zhong Nanshan honoured Zhong Nanshan, who first identified SARS, received an honorary degree at a ceremony celebrating Edinburgh’s Chinese links ALSO INSIDE Edinburgh is to play host to the first British centre for human and avian flu research, while the Reid Concert Hall Museum will house a unique clarinet collection 60282_Edit_Summer07 2/5/07 02:01 Page 2 60282_Edit_Summer07 2/5/07 09:35 Page 3 Contents 16xx Foreword Welcome to the Summer 2007 edition of Edit, and many thanks to everyone who contacted us with such positive feedback about our new design. A recent ceremony in Beijing celebrated the University’s links with China and saw Professor 18 Zhong Nanshan receiving an honorary degree; Edit takes a closer look at our connections – historical and present-day – to that country (page 14). The discovery of H5N1 on a turkey farm in Norfolk earlier this year meant avian flu once 14 20 again became headline news. Robert Tomlinson reports on plans to establish a cutting-edge centre at the University to research the virus Features (page 16). The focus of our third feature is the Shackleton 14 Past, Present and Future Bequest, an amazing collection of clarinets Developing links between China and Edinburgh. recently bequeathed to the University that will be housed in the Reid Concert Hall Museum 16 From Headline to Laboratory (page 20). Edinburgh takes lead in Britain’s fight against avian flu. Anne Borthwick 20 Art meets Science Editor The remarkable musical legacy of the paleoclimatologist Editor who championed the clarinet. -

Cloning: a Select Chronology, 1997-2003

Order Code RL31211 Report for Congress Received through the CRS Web Cloning: A Select Chronology, 1997-2003 Updated March 10, 2003 Mary V. Wright Information Research Specialist Information Research Division Congressional Research Service ˜ The Library of Congress Summary This is a selected chronology of the events surrounding and following the cloning of a sheep from a single adult sheep cell by Scottish scientists, which was announced in February 1997. The project was cosponsored by PPL Therapeutics, Edinburgh, Scotland, which has applied for patents for the techniques used. This chronology also addresses subsequent reports of other cloning experiments, including the first one using human cells. Information on presidential actions and legislative activities related to the ethical and moral issues surrounding cloning is provided, as well as relevant Web sites. More information on cloning and on human embryo research can be found in CRS Report RL31015, Stem Cell Research and CRS Report RS21044, Background and Legal Issues Related to Stem Cell Research. This report will be updated as necessary. Contents Chronology .......................................................1 1997 ........................................................1 1998 ........................................................2 1999 ........................................................3 2000 ........................................................4 2001 ........................................................5 2002 ........................................................6 -

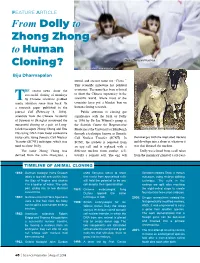

From Dolly to Zhong Zhong to Human Cloning?

Feature Article From Dolly to Zhong Zhong to Human Cloning? Zhong Zhong and Hua Hua (Photo courtesy: www.engadget.com) Biju Dharmapalan formal and ancient name for “China.” This scientific milestone has political HE recent news about the overtones. The name has been selected successful cloning of monkeys to show the Chinese supremacy in the by Chinese scientists grabbed scientific world, where most of the T dolly.roslin.ed.ac.uk) media attention some time back. In countries have put a blanket ban on a research paper published in the human cloning research. journal Cell (February 8, 2018), Public attention in cloning got Photo courtesy: scientists from the Chinese Academy significance with the birth of Dolly ( of Sciences in Shanghai announced the in 1996 by Sir Ian Wilmut’s group at successful cloning of a pair of Long- the Scottish Centre for Regenerative tailed macaques Zhong Zhong and Hua Medicine at the University of Edinburgh Dolly and her surrogate mother Hua using DNA from foetal connective through a technique known as Somatic tissue cells, using Somatic Cell Nuclear Cell Nuclear Transfer (SCNT). In then merges with the implanted nucleus Transfer (SCNT) technique, which was SCNT, the nucleus is removed from and develops into a clone of whatever it used to clone Dolly. an egg cell and is replaced with a was that donated the nucleus. The name Zhong Zhong was different nucleus from another cell, Dolly was cloned from a cell taken derived from the term Zhonghua, a usually a somatic cell. The egg cell from the mammary gland of a six-year- TIMELINE OF ANIMAL CLONING 1894: German biologist Hans Driesch used Xenopus laevis to show Schatten creates Tetra, a rhesus takes a two-cell sea urchin from that nuclei from specialised cells macaque, using embryo splitting the Bay of Naples and shakes still held the potential to be any technique. -

The Royal Society of Edinburgh Issue 15 • Winter 2006

news THE ROYAL SOCIETY OF EDINBURGH ISSUE 15 • WINTER 2006 RESOURCE THE NEWSLETTER OF SCOTLAND’S NATIONAL ACADEMY Microcrystals promise major medical benefits A new technology being developed in Scotland could transform the treatment of many diseases by enabling protein medicines that currently need to be injected, to be taken with an inhaler. Recognising the importance of this breakthrough, Dr Marie Claire Parker was presented with the nation’s top award for innovation at a Ceremony held in the Royal Museum of Scotland on 27 October 2006. Dr Parker is CEO of XstalBio Ltd, a University of Glasgow and University of Strathclyde spin-out company, which developed as a result of an RSE/Scottish Enterprise Enterprise Fellowship held by Dr Parker in 2001. The Gannochy Trust Innovation Award of the Royal Society of Edinburgh has been created to encourage and reward Scotland’s young innovators for work which benefits Scotland’s wellbeing. This coveted award also carries a cheque for £50,000 and a specially commissioned gold medal, which was presented to Dr Parker by the President of the RSE, Sir Michael Atiyah. Dr Parker plans to use the £50,000 award to help develop the manufacturing process of stable, cost-effective vaccines and the advancement of a high quality biotechnology manufacturing company in Scotland, boosting our economy. Events around Scotland Christmas Lecture 2006 International Exchanges Recognising Excellence GANNOCHY TRUST INNOVATION AWARD OF THE ROYAL SOCIETY OF EDINBURGH Entitled “Protein-coated Microcrystal (PCMC) Technology”, Dr Parker’s new process can attach proteins such as insulin to crystals that are so tiny (between one and five thousandths of a millimetre) that they can be inhaled, allowing the drug to enter the body via the lung. -

Antony John Clark OBE, FRSE This Obituary First Appeared in The

Antony John Clark OBE, FRSE This obituary first appeared in The Guardian on 25 August 2004 http://www.guardian.co.uk/science/2004/aug/25/obituaries.health The sudden death of Professor John Clark, at the age of 52, has robbed Britain of a world leader in animal science and biotechnology, and an individual whose commitment to science was based on a genuine concern for others. A visionary, energetic and resolute leader, he made outstanding contributions not only in research, but also in translating it to the commercial environment. Clark was director of the Roslin Institute, near Edinburgh, one of the world's leading centres for research on farm and other animals, funded by the Biotechnology and Biological Science Council. He pioneered the development of techniques for the genetic modification of livestock that led to the cloning techniques and the birth, in 1996, of Dolly the sheep, the first animal to be cloned from an adult cell. This event created entirely new opportunities in research and regenerative medicine. Appointed to the then Animal Breeding Research Organisation in 1985, Clark soon assumed leadership of a project to produce human proteins in the milk of sheep. Its success required an understanding of the mechanisms that regulate the functioning of genes, the technical ability to manipulate DNA sequences and methods for the introduction of gene sequences into sheep embryos. While these are now commonplace, this was not the case at the time, and the project was technically challenging. The birth, in 1990, of Tracy, the first sheep to produce very large quantities of human protein in her milk - alpha-1-antitrypsin for the treatment of cystic fibrosis - was a milestone in the field, and a success that laid the foundation for the continuing reputation of the Roslin Institute (as it became in 1993) as pioneers in transgenic technology. -

Edinburgh Research Explorer

Edinburgh Research Explorer Genetically engineering milk Citation for published version: Whitelaw, CBA, Joshi, A, Kumar, S, Lillico, SG & Proudfoot, C 2016, 'Genetically engineering milk', Journal of Dairy Research, vol. 83, no. 1, pp. 3-11. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022029916000017 Digital Object Identifier (DOI): 10.1017/S0022029916000017 Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Peer reviewed version Published In: Journal of Dairy Research General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 25. Sep. 2021 Short title: Genetically engineering milk Genetically engineering milk C. Bruce A. Whitelaw1,*, Akshay Joshi1, Satish Kumar2, Simon G. Lillico1 and Chris Proudfoot1. The Roslin Institute and Royal (Dick) School of Veterinary Sciences, University of Edinburgh, Easter Bush CamPus, Midlothian EH25 9RG, UK1 Centre for Cellular and Molecular Biology, Hyderabad, India2 * For correspondence: [email protected] Received 22nd December 2015 and accepted for Publication 1st January 2016 It has been thirty years since the first genetically engineered animal with altered milk composition was rePorted. -

Annual Review 2005/06 (2.77 MB PDF)

01 The University of Edinburgh Annual Review 2005/06 www.ed.ac.uk 2005/06 Our Mission The University’s mission is the advancement and dissemination of knowledge and understanding. As a leading international centre of academic excellence, the University has as its core mission: • to sustain and develop its position as a research and teaching institution of the highest international quality and to benchmark its performance against world-class standards; • to provide an outstanding educational environment, supporting study across a broad range of academic disciplines and serving the major professions; • to produce graduates equipped for high personal and professional achievement; and • to contribute to society, promoting health, economic and cultural wellbeing. As a great civic university, Edinburgh especially values its intellectual and economic relationship with the Scottish community that forms its base and provides the foundation from which it will continue to look to the widest international horizons, enriching both itself and Scotland. 59603_EdUni_AR2006 1 11/1/07 08:14:20 “ At the heart of all that we achieve are our students and staff, and our alumni and friends, and I must thank the entire University community most warmly for the great achievements of the last year.” 59603_EdUni_AR2006 2 11/1/07 08:14:20 03 The University of Edinburgh Annual Review 2005/06 www.ed.ac.uk 2005/06 Principal’s Foreword Each year the Annual Review presents us with the of these categories. It is these solid foundations opportunity to capture as best we can a fl avour which form the basis for the confi dent, forward- of the life of the University over the previous year.