Creative Thinking and Problem Solving Through Cross-Application

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ultimate-Bridal-Shopping-Guide.Pdf

Bridal Shopping Handbook Copyright ©2015 Omo Alo All rights reserved. First Edition No part of this book shall be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information retrieval system without written permission from the author. Although every precaution has been taken in the preparation of this book, the author assumes no responsibility for errors or omissions. Neither is any liability assumed for damages or loss of earnings resulting from the use of the information contained herein 2 Contents Chapter 1: Introduction……………………………………………………………. 4 Chapter 2: 3 Must Know Tips to Find Your Dream Dress………………………… 5 Chapter 3: Choosing the Right Dress for Your Body Shape …………………….... 8 Chapter 4: Get a Tiny Waist Look in Your Wedding Dress ………………………. 14 Chapter 5: Different Bridal Fabrics…………………………………………………18 Chapter 6: Bridal Inspiration from Past Estilo Moda Brides ……………………… 21 Chapter 7: Wedding Dress Shopping ……………………………………………... 43 Chapter 8: Conclusion …………………………………………………………….. 46 3 Chapter 1 Introduction Meet Eliza, who got married a few years ago and still wishes every day that she had worn a different wedding dress something different for her wedding. Unfortunately, she’s about 3 years too late now. She still hopes her husband would be open to a marriage blessing and then she can finally wear her dream dress. Long before Steven proposed to Eliza, she knew what her dream wedding dress would look like. She was sure it would be perfect for her and she knew what every last detail would be. She wanted to look like a modern day princess. The bodice would have been reminiscent of Grace Kelly’s wedding dress bodice: lightly beaded lace, high neck but with cap sleeves rather than long sleeves. -

Making Mannequins, Part 2

Making mannequins, part 2 Fosshape mannequins This information sheet outlines how to make simple, bespoke mannequins for displaying garments. A garment displayed on a correctly fitted mannequin will reveal its style and shape but also ensures that there is no strain on the fabric. In the Conservation Unit of the Museum of Applied Arts and Sciences, we frequently make Fosshape mannequins and accessory supports in our exhibitions. Using Fosshape material to make mannequins is simple, creative, inexpensive, quick, clean and very effective. What is Fosshape? Fosshape is a low melt, non-woven, polyester fabric, similar in appearance to felt but stiffens when heated with steam. It is lightweight, breathable and easy to cut and stitch. A piece of Fosshape can be fitted onto a form, such as a dressmaker’s mannequin or mannequin parts, such as heads, legs, arms. Applying heat and pressure to the Fosshape will cause it to stiffen and take on the Example of a silk wedding dress, from 1887, on an shape of the form beneath it. Fosshape will shrink invisible mannequin. MAAS Collection, donated by Mrs James, 1986. 86/648 by 15% and become smoother when it is heat activated. It can be bought by the metre from milliner suppliers. Fosshape comes in white and black and 3 different weight grades (300, 400 and 600 grams per sq/metre). Uses Fosshape can be used to create mannequins and accessory supports for hats, gloves or even mermaid tails. It can also be used to create invisible forms which allows a garment to be viewed as it is without the distraction of a mannequin. -

Optical Illusions and Effects on Clothing Design1

International Journal of Science Culture and Sport (IntJSCS) June 2015 : 3(2) ISSN : 2148-1148 Doi : 10.14486/IJSCS272 Optical Illusions and Effects on Clothing Design1 Saliha AĞAÇ*, Menekşe SAKARYA** * Associate Prof., Gazi University, Ankara, TURKEY, Email: [email protected] ** Niğde University, Niğde, TURKEY, Email: [email protected] Abstract “Visual perception” is in the first ranking between the types of perception. Gestalt Theory of the major psychological theories are used in how visual perception realizes and making sense of what is effective in this process. In perception stage brain takes into account not only stimulus from eyes but also expectations arising from previous experience and interpreted the stimulus which are not exist in the real world as if they were there. Misperception interpretations that brain revealed are called as “Perception Illusion” or “Optical Illusion” in psychology. Optical illusion formats come into existence due to factors such as brightness, contrast, motion, geometry and perspective, interpretation of three-dimensional images, cognitive status and color. Optical illusions have impacts of different disciplines within the study area on people. Among the most important types of known optical illusion are Oppel-Kundt, Curvature-Hering, Helzholtz Sqaure, Hermann Grid, Muller-Lyler, Ebbinghaus and Ponzo illusion etc. In fact, all the optical illusions are known to be used in numerous area with various techniques and different product groups like architecture, fine arts, textiles and fashion design from of old. In recent years, optical illusion types are frequently used especially within the field of fashion design in the clothing model, in style, silhouette and fabrics. The aim of this study is to examine the clothing design applications where optical illusion is used and works done in this subject. -

Bare Witness

are • THE METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF ART "This is a backless age and there is no single smarter sunburn gesture than to hm'c every low-backed cos tume cut on exactly the same lines, so that each one makes a perfect frame for a smooth brown back." British Vogue, July 1929 "iVladame du V. , a French lady, appeared in public in a dress entirely a Ia guil lotine. That is to say ... covered with a slight transparent gauze; the breasts entirely bare, as well as the arms up as high as the shoulders.... " Gemleman's A·1agazine, 1801 "Silk stockings made short skirts wearable." Fortune, January 1932 "In Defence ofSh** ld*rs" Punch, 1920s "Sweet hem·ting matches arc very often made up at these parties. It's quite disgusting to a modest eye to see the way the young ladies dress to attract the notice of the gentlemen. They are nearly naked to the waist, only just a little bit of dress hanging on the shoulder, the breasts are quite exposed except a little bit coming up to hide the nipples." \ Villiam Taylor, 1837 "The greatest provocation oflust comes from our apparel." Robert Burton, Anatomy ofi\Jelancholy, 1651 "The fashionable woman has long legs and aristocratic ankles but no knees. She has thin, veiled arms and fluttering hands but no elbows." Kennedy Fraser, The Fashionahlc 1VIind, 1981 "A lady's leg is a dangerous sight, in whatever colour it appears; but, when it is enclosed in white, it makes an irresistible attack upon us." The Unil'ersol !:lpectator, 1737 "'Miladi' very handsome woman, but she and all the women were dccollctees in a beastly fashion-damn the aristocratic standard of fashion; nothing will ever make me think it right or decent that I should see a lady's armpit flesh-folds when I am speaking to her." Georges Du ~ - laurier, 1862 "I would need the pen of Carlyle to describe adequately the sensa tion caused by the young lady who first tr.od the streets of New York in a skirt .. -

Hardin Junior High School Dance Rules and Dress Code Guidelines

Hardin Junior High School Dance Rules and Dress Code Guidelines Location: School Cafeteria Dates & Themes: February 15: Valentine Masquerade (Formal) TIME: 5:30 p.m. to 8: 0 p.m. 3 ***No one is to leave the dance without a parent or guardian signing them out. If a student is to leave with another student the parent or guardian needs to notify the front office. Valentine Masquerade (Formal) Girls: • Open back dresses are allowed as long as they are not extremely low cut in the back, may not extend beyond mid-back. • May wear strapless dress if it is not too revealing (see next dress stipulation) • The top of the dress should not be extremely low-cut in the front (no cleavage) • No bare stomachs or midriffs showing; dresses may be a two-piece style but must not show the stomach or midriff when arms are at ones side. • Undergarments should not be visible • No see-through apparel • No dress/skirt slits above the mid-thigh • No extremely tight garments • No tattoos or body piercing showing Boys: • Collared shirt, tuxedo, suit, dress pants or jeans without rips or holes. Shirt tucked in and a belt. • Tie, bow tie and sports coat optional. • Undergarments should not be visible • No see-through apparel • Must be clean shaven • No tattoos or body piercing showing ***Any student who is not in dress code will be required to correct the violation before entering the dance. If you are in doubt of your attire, bring a picture (front, back, side) and get approval. Important Contacts: HJH phone number 936-298-2054 Principal Jennifer Stein [email protected] Student Council Advisor Kim Collins & Tiffany Templeton [email protected] & [email protected] . -

Moses Lake Christian Academy Secondary Dress Code

Moses Lake Christian Academy Secondary Dress Code Students are encouraged to dress in a manner that is respectful, honors God and fosters a readiness to learn. The dress code provides a range of what is acceptable or unacceptable in our school setting, yet is flexible enough to allow students to be responsible for their own personal choices in attire. Even though the enforcement of the dress code is everyone’s responsibility, the Administration maintains the authority to make judgements regarding the implementation of the policy. Guiding Principles: Clean, neat, modest, safe with no holes and no frays. Item Expectation Hair Clean, neat, combed with both eyes visible. Logos Clothing containing images or writing that is inappropriate, offensive or contradicts our Statement of Faith must be avoided. Clothing, jewelry and other wearables shall be free of writing, pictures, and/or any insignia that: (1) are crude, vulgar, violent, profane, prejudicial, racial, associated with any hate group, or sexually suggestive; (2) advocate or reference the use of drugs, alcohol, tobacco, or weapons. Shirts, Tops Tops need to be of an appropriate length so that when arms are raised above the head, the body does not expose any skin. The neckline needs to be high enough to cover any exposure of cleavage. Acceptable: T-shirts, long or short sleeve shirts, sweat shirts, shirts with cap sleeve (minimum of 3” across the shoulder and fitted around the arm). Unacceptable: Half shirts, tank tops, pajama top, tight fitting, low cut, backless or sheer back, spaghetti straps, off the shoulder, sheer or see-through top and camisoles worn alone. -

Red Is the Colour for a Dazzling Wedding Strapless Tops And

A wedding dress with refined lines Brides have access The flared skirt remains a popular option for trim cut that allows for fluid and graceful the bride. This year however, lines are much movement. Some models only decorate the to increasingly more refined, with both the ever-popular A- bodice, allowing the graceful cut to accent the line and narrow, elegant skirts becoming charm of the simple but beautiful skirt. varied accessories increasingly popular as well. A delicately ornamented bustier with a trim With the emergence of a romantic tendency, cut can be combined with a tight-fitting skirt more fluid styles, including the princess look, for a dress that is casually refined. Design and and trains are increasingly being sought after. innovation is the key. A bodice decorated with Grace and beauty are the order of the day for silk and flowers and an A-line skirt comple- ever more elaborate and often delicate models ment the bride’s figure. In cases where the found in original creations and modern styles bodice is more understated and only orna- that stress good taste. Delicate ornamentation, mented with gems on the borders, the cut is flowers and understated gem embroidery such as to offset the gems. Combined with a make for a discreetly tasteful bodice that flows simple A-line skirt, this makes for a wedding into an equally discreetly adorned skirt, with a dress that is the height of elegance and refine- ment. The pinnacle of the sumptuous wedding A bustier-style dress with a discreetly dress is to be found in a tasteful bodice com- ornamented bodice in combination with bined with a flared skirt and a majestic train, a refined, close-fitting skirt. -

Claus Meyer Expands His Culinary Domain

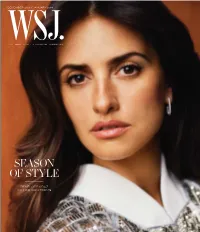

SEASON OF STYLE penÉlope cruz on her own terms RALPH LAUREN The Ricky Bag Ricky Lauren RALPHLAUREN.COM/RICKY RALPH LAUREN The Ricky Bag “My wife Ricky is my muse. Her personal style and natural beauty have always been my inspiration.” ® , Inc. J 12 ® Watch in high-tech ceramic. Moonphase complication with aventurine counter. Available in classic or diamond version. ©2013 CHANEL chAnel boutiques 800.550.0005 chAnel.coM ASPORTINGLIFE! 1-800-441-4488 Hermes.com INTRODUCING © 2013 Estée Lauder Inc. BE AN INSPIRATION #modernmuse TO BREAK THE RULES, YOU MUST FIRST MASTER THEM. THE WATCH THAT BROKE ALL THE RULES, REBORN. IN 1972, THE ORIGINAL ROYAL OAK SHOCKED THE WATCHMAKING WORLD AS THE FIRST HAUTE HOROLOGY SPORTS WATCH TO TREAT STEEL AS A PRECIOUS METAL. TODAY THE NEW ROYAL OAK COLLECTION STAYS TRUE TO THE SAME PRINCIPLES SET OUT IN LE BRASSUS ALL THOSE YEARS AGO: “BODY OF STEEL, HEART OF GOLD.” OVER 130 YEARS OF HOROLOGICAL CRAFT, MASTERY AND FINE DETAILING LIE INSIDE THIS ICONIC MODERN EXTERIOR; THE PURPOSEFUL ROYAL OAK ARCHITECTURE NOW EXPRESSED IN 41MM DIAMETER. FROM AVANT-GARDE TO ICON. AUDEMARS PIGUET BOUTIQUES. 646.375.0807 NEW YORK: 65 EAST 57TH STREET, NY. 888.214.6858 BAL HARBOUR: BAL HARBOUR SHOPS, FL. 866.595.9700 ROYAL OAK AUDEMARSPIGUET.COM IN STAINLESS STEEL. SELFWINDING MANUFACTURE MOVEMENT. PROUD PARTNER OF Light, Purity, StiLLneSS Some SecretS are for whiSPering www.royalmansour.com ART DIR: PAUL MARCIANO GUESS?©2013 NORTH STAR COLLECTION For starry nights, diamonds and white gold. NEW YORK CHICAGO LONDON COPENHAGEN HONG KONG TOKYO WWW.G EORGJENSEN.COM ® h aC CO 3 01 ©2 WILL See the film at COaCh.COm #COaChNeWYORKStORieS december 2013 / january 2014 36 EDITOR’S LETTER 40 CONTRIBUTORS 46 COLUMNISTS on Indulgence 49 gIfT gUIDE: HOME CHIC HOME A room-by-room register of the season’s best presents. -

6 Michigan State News, East Lansing

MICHIGAN STATE UNIVERSITY East Lansing, Michigan Wednesday, October 16, 1968 2 Michigan State News. East Lansing, Michigan C o w b o ys, robbers in style By PAT ANSTETT The style most popularly This countryside look is given Associate Campos Editor adapted by returning-to-campus its finishing touch with scarfs, Fall fashions are offering females is the look of the “wild, tied in necktie fashion, worn as clothing-minded coeds a wide wild, west,” almost a reaction an ascot or casually thrown selection of styles and fabrics. to the Romantic ruffles and around the shoulders. Coeds may either don buck little girl dresses popular last Adorning this rugged look are skin and suede and toss a year. other typically unfeminine dec paisley scarf in cowboy-like This lode reminiscent of Pon- orations, with buckles and fashion around their necks or derosa territory, is characterized heavy zippers especially pre they may, in the spirit of Fay by straight lines, heavy “un dominate. Dunaway, adorn themselves feminine” materials of leather For the coed desiring an oc with low-hanging, v’d or ruffled and suede and an abpndance of cassional change from this blouses, topped with the Ro scarfs, vests,, ascots and ties. somewhat “unfeminine” look mantic look of a beret. Leather is especially popular last year’s fashions inspired by Whatever the style coeds may this fall, and for once, the ma Bonnie and Clyde are again pop prefer, fall fashion definitely terial has become so widely ular this year. promises diverse lines of cloth adapted that even budget- Ruffle and lace-loving coeds ing, especially to the delight watching coeds can afford some can find fall fashions suited to of coeds tired of the seemingly of these new styles. -

Eslpod 422 Guide.Pdf

English as a Second Language Podcast www.eslpod.com ESL Podcast 422 – Shopping for Underwear GLOSSARY underwear – clothes worn underneath one’s regular clothing that shouldn’t be seen normally * I need to do laundry because I don’t have any more clean underwear! unmentionables – underwear; a funny way to refer to underwear, as if it were indecent or inappropriate to talk about underwear in a conversation * Whenever Aunt Peggy talks about underwear, she gets embarrassed, turns red, and refers to the clothes as “unmentionables.” lingerie – women’s underwear, especially when it is very fancy, sexy, and/or expensive * Many stores sell red and pink lingerie in the weeks before Valentine’s Day. bra – a type of underwear worn by women that goes over their shoulders and around their chest to support their breasts * How old was your daughter when she started wearing a bra for the first time? underwire – a curved piece of metal that is sewn into some bras to provide extra support for large breasts * Some women think that wearing a bra with an underwire is uncomfortable, but most women who have very large breasts like them. strapless – a piece of clothing that does not have any fabric going over a woman’s shoulder, usually a dress or bra * Beth plans to wear a strapless dress to the dance, but she needs to buy a strapless bra to wear with it. cup – the part of a bra that has a rounded shape and fits over one breast available in sizes AAA (the smallest) through DDD (the biggest) * During pregnancy, her breasts grew and her bra cup size went from a B to a C. -

Oakmont High School Dress Code

Oakmont High School Dress Code Parents are asked to monitor the students in their care and counsel them on appropriate choices. The following are the basic requirements of the Dress Code: Students are expected to wear clean, neat, and well-maintained clothing. Shoes must be worn on school grounds at all times. Printing, logos and/or graphics depicting drugs, alcoholic beverages, tobacco, or messages that are sexually suggestive, or disrespectful, are prohibited. Clothing with graphics of weapons are prohibited. Clothing or accessories that are indicators of gang involvement or emulation are prohibited. This includes the wearing of bandanas. Board Policy 5131.20 Strapless tops, halter tops, backless tops, tube tops, and bare midriffs are prohibited. Tops revealing cleavage are prohibited. A strap on each shoulder is required. Undergarments are not to be visible. Students should exercise caution with distressed shorts or jeans that have holes where undergarments could show. Under shirt tank tops and tank tops with low cut arm holes are not permitted. Short shorts are prohibited. Skirts and dresses must reach mid-thigh. Short skirts with slits are prohibited. More stringent requirements may be imposed in specific classes for safety reasons (such as physical education and shop classes). The Health Academy and/or special programs may develop specific guidelines for their members as well. Violations of the dress code may include: Strapless dress or shirt Halter shirt Short shorts (without hems, with holes, etc.) Jeans or pants with holes where undergarments could show Inappropriate language or images on t-shirt (including drug or alcohol references) Sagging pants Visible underwear (including bras and bandeaus) Short skirt or dress Bare midriff Muscle t-shirt Cleavage Any clothing that is revealing Consequences for dress code violations are: 1. -

Exploring the Significance of Yok Dok Textiles for Education Purposes

EXPLORING THE SIGNIFICANCE OF YOK DOK TEXTILES FOR EDUCATION PURPOSES By MRS. Supamas JIAMRUNGSAN A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Doctor of Philosophy DESIGN ARTS (INTERNATIONAL PROGRAM) Graduate School, Silpakorn University Academic Year 2018 Copyright of Graduate School, Silpakorn University - โดย นางศุภมาส เจียมรังสรรค์ วิทยานิพนธ์นี้เป็นส่วนหนึ่งของการศึกษาตามหลักสูตรปรัชญาดุษฎีบัณฑิต สาขาวิชาศิลปะการออกแบบ แบบ 1.1 ปรัชญาดุษฎีบัณฑิต(หลักสูตรนานาชาติ) บัณฑิตวิทยาลัย มหาวิทยาลัยศิลปากร ปีการศึกษา 2561 ลิขสิทธิ์ของบัณฑิตวิทยาลัย มหาวิทยาลัยศิลปากร EXPLORING THE SIGNIFICANCE OF YOK DOK TEXTILES FOR EDUCATION PURPOSES By MRS. Supamas JIAMRUNGSAN A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Doctor of Philosophy DESIGN ARTS (INTERNATIONAL PROGRAM) Graduate School, Silpakorn University Academic Year 2018 Copyright of Graduate School, Silpakorn University Title EXPLORING THE SIGNIFICANCE OF YOK DOK TEXTILES FOR EDUCATION PURPOSES By Supamas JIAMRUNGSAN Field of Study DESIGN ARTS (INTERNATIONAL PROGRAM) Advisor PAIROJ JAMUNI Graduate School Silpakorn University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Doctor of Philosophy Dean of graduate school (Associate Professor Jurairat Nunthanid, Ph.D.) Approved by Chair person (Professor EAKACHAT JONEURAIRATANA ) Advisor (Associate Professor PAIROJ JAMUNI , Ed.D.) Co Advisor (Assistant Professor VEERAWAT SIRIVESMAS , Ph.D.) Examiner (Assistant Professor NAMFON LAISTROOGLAI , Ph.D.) External Examiner (Professor Mustaffa Halabi Bin Azahari , Ph.D.) D ABSTRACT 57155955 : Major DESIGN ARTS (INTERNATIONAL PROGRAM) Keyword : Pha Yok Dok, Brocade, Education MRS. SUPAMAS JIAMRUNGSAN : EXPLORING THE SIGNIFICANCE OF YOK DOK TEXTILES FOR EDUCATION PURPOSES THESIS ADVISOR : ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR PAIROJ JAMUNI, Ed.D. This research is concerned with how Thai brocade techniques. That called Pha Yok Dok in Thai with qualitative research was used in this study. There is a need use examine the current of the Yok Dok Textile in the Thailand communities.