Wedding Dress Purchase Intentions of Tattooed Brides

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

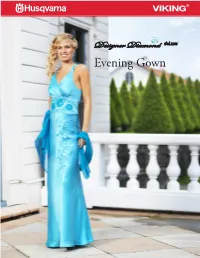

Evening Gown Sewing Supplies Embroidering on Lightweight Silk Satin

Evening Gown Sewing supplies Embroidering on lightweight silk satin The deLuxe Stitch System™ improves the correct balance • HUSQVARNA VIKING® DESIGNER DIAMOND between needle thread and bobbin thread. Thanks to the deLuxe™ sewing and embroidery machine deLuxe Stitch System™ you can now easily embroider • HUSQVARNA VIKING® HUSKYLOCK™ overlock with different kinds of threads in the same design. machine. • Use an Inspira® embroidery needle, size 75 • Pattern for your favourite strap dress. • Turquoise sand-washed silk satin. • Always test your embroidery on scraps of the actual fabric with the stabilizer and threads you will be using • Dark turquoise fabric for applique. before starting your project. • DESIGNER DIAMOND deLuxe™ sewing and • Hoop the fabric with tear-away stabilizer underneath embroidery machine Sampler Designs #1, 2, 3, 4, 5. and if the fabric needs more support use two layers of • HUSQVARNA VIKING® DESIGNER™ Royal Hoop tear-away stabilizer underneath the fabric. 360 x 200, #412 94 45-01 • Endless Embroidery Hoop 180 x 100, #920 051 096 Embroider and Sew • Inspira® Embroidery Needle, size 75 • To insure a good fit, first sew the dress in muslin or • Inspira® Tear-A-Way Stabilizer another similar fabric and make the changes before • Water-Soluble Stabilizer you start to cut and sew in the fashion fabric for the dress. • Various blue embroidery thread Rayon 40 wt • Sulky® Sliver thread • For the bodice front and back pieces you need to embroider the fabric before cutting the pieces. Trace • Metallic thread out the pattern pieces on the fabric so you will know how much area to fill with embroidery design #1. -

Business Professional Dress Code

Business Professional Dress Code The way you dress can play a big role in your professional career. Part of the culture of a company is the dress code of its employees. Some companies prefer a business casual approach, while other companies require a business professional dress code. BUSINESS PROFESSIONAL ATTIRE FOR MEN Men should wear business suits if possible; however, blazers can be worn with dress slacks or nice khaki pants. Wearing a tie is a requirement for men in a business professional dress code. Sweaters worn with a shirt and tie are an option as well. BUSINESS PROFESSIONAL ATTIRE FOR WOMEN Women should wear business suits or skirt-and-blouse combinations. Women adhering to the business professional dress code can wear slacks, shirts and other formal combinations. Women dressing for a business professional dress code should try to be conservative. Revealing clothing should be avoided, and body art should be covered. Jewelry should be conservative and tasteful. COLORS AND FOOTWEAR When choosing color schemes for your business professional wardrobe, it's advisable to stay conservative. Wear "power" colors such as black, navy, dark gray and earth tones. Avoid bright colors that attract attention. Men should wear dark‐colored dress shoes. Women can wear heels or flats. Women should avoid open‐toe shoes and strapless shoes that expose the heel of the foot. GOOD HYGIENE Always practice good hygiene. For men adhering to a business professional dress code, this means good grooming habits. Facial hair should be either shaved off or well groomed. Clothing should be neat and always pressed. -

The Wildflower Weddings

The weddingsWildflower lake hemet “Like the wildflower; You must allow yourself to grow in all the places people never thought you would.” –E.V. Can you see yourself exchanging your vows in a picturesque out- door natural setting with pine trees, mountains, green meadows and a sparkling lake as your backdrop? The Wildflower is a woodsy rustic chic wedding for the couple that is free spirited, lovers of the outdoors, and admirers of simplicity. Our packages are designed for an uncompli- cated stress free experience. We empower you to create exactly what you want for your special day. Like a wildflower, you are not bound to any specific way or idea. You can use our Preferred Service Partners or you can bring in your own vendors. Whether you will be hiring your own caterer or having the family cook, you are free to bring it in without any corkage fee. The price that you will be paying for the venue space covers everything with no hidden expenses. Ceremony and Reception Sites The natural scenic setting of the Forest Glen Wedding Site with a view of the mountains, seasonal wildflowers, trees and lake is perfect place to accommodate a very large wedding. It is separated from the campground. The other option for your ceremony and reception is the lovely shaded Forest Blossom Park Wedding Site. Our manicured park with tall pines, large dance area with romantic market lights is a beautiful site for any size wedding. Both sites have handcrafted stone fire pits. We will set up your white wedding folding chairs and a simple but adorable wedding arbor in the configuration you would like. -

Updated 5.3 EPK 2019 Press Releasefinal

Meredith Ekstedt Senior PR Manager Lands’ End 212-302-6100 [email protected] Lands’ End Showcases Inclusive Swimsuit Offerings for Summer 2019 The Company Offers Over 19,000 Mix and Match Opportunities, 21 One-piece Styles in 78 Colors and Patterns, 23 Cover Up Choices in 96 Colors and Patterns DODGEVILLE, Wis. – May 7, 2019 – Lands’ End (NASDAQ: LE), a leading uni-channel retailer known for high-quality apparel for the whole family, is highlighting its expansive range of inclusive swimwear designed for every body. With over 19,000 mix and match top-and-bottom options, 21 one-piece styles, and 23 cover up choices – ranging from bright yellows to bold prints, and sun protection to versatile beach wear – Lands’ End ensures that everyone can stay on top of this summer’s latest trends and feel their best on the beach. The company’s expansive swimwear collection is available in a range of inclusive sizes, including regular, plus, long, long plus, petite, petite plus and mastectomy. “We believe the best beach body is the one you already have,” said Chieh Tsai, chief product officer, Lands’ End. “We designed our swimwear collection so that everyone can look and feel great in and out of the water while participating in this season’s top style trends, no matter your size, shape or coverage preference.” Lands’ End offers a variety of swimwear in a wide range of inclusive sizes, cuts, coverage options, colors and patterns to meet this season’s top trends: • Bold & Animal Prints: A staple on the runway for many seasons, you can easily incorporate this trend into your swim wardrobe by mixing and matching a bold print with a solid separate, or dive fully into this trend with an animal printed one piece. -

Ultimate-Bridal-Shopping-Guide.Pdf

Bridal Shopping Handbook Copyright ©2015 Omo Alo All rights reserved. First Edition No part of this book shall be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information retrieval system without written permission from the author. Although every precaution has been taken in the preparation of this book, the author assumes no responsibility for errors or omissions. Neither is any liability assumed for damages or loss of earnings resulting from the use of the information contained herein 2 Contents Chapter 1: Introduction……………………………………………………………. 4 Chapter 2: 3 Must Know Tips to Find Your Dream Dress………………………… 5 Chapter 3: Choosing the Right Dress for Your Body Shape …………………….... 8 Chapter 4: Get a Tiny Waist Look in Your Wedding Dress ………………………. 14 Chapter 5: Different Bridal Fabrics…………………………………………………18 Chapter 6: Bridal Inspiration from Past Estilo Moda Brides ……………………… 21 Chapter 7: Wedding Dress Shopping ……………………………………………... 43 Chapter 8: Conclusion …………………………………………………………….. 46 3 Chapter 1 Introduction Meet Eliza, who got married a few years ago and still wishes every day that she had worn a different wedding dress something different for her wedding. Unfortunately, she’s about 3 years too late now. She still hopes her husband would be open to a marriage blessing and then she can finally wear her dream dress. Long before Steven proposed to Eliza, she knew what her dream wedding dress would look like. She was sure it would be perfect for her and she knew what every last detail would be. She wanted to look like a modern day princess. The bodice would have been reminiscent of Grace Kelly’s wedding dress bodice: lightly beaded lace, high neck but with cap sleeves rather than long sleeves. -

Download Download

Anna-Katharina Höpflinger and Marie-Therese Mäder “What God Has Joined Together …” Editorial Fig. 1: Longshot from the air shows spectators lining the streets to celebrate the just-married couple (PBS, News Hour, 21 May 2018, 01:34:21).1 On 19 May 2018 the royal wedding of Prince Harry and Meghan Markle flooded the television channels. Millions of spectators around the globe watched the event on screens and more than 100,000 people lined the streets of Windsor, England, to see the newly wed couple (fig.1).12 The religious ceremony formed the center of the festivities. It took place in St. George’s Chapel at Windsor Castle, attended by 600 invited guests. While this recent example is extraordinary in terms of public interest and financial cost, traits of this event can also be found in less grand ceremonies held by those of more limited economic means. Marriage can be understood as a rite of passage that marks a fundamental transformation in a person’s life, legally, politically, and economically, and often 1 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=j51O4lf232w [accessed 29 June 2018]. 2 https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2018/may/19/a-moment-in-history-royal-wedding- thrills-visitors-from-far-and-wide [accessed 29 June 2018]. www.jrfm.eu 2018, 4/2, 7–21 Editorial | 7 DOI: 10.25364/05.4:2018.2.1 in that person’s self-conception, as an individual and in terms of his or her place in society.3 This transformation combines and blurs various themes. We focus here on the following aspects, which are integral to the articles in this issue: the private and the public, tradition and innovation, the collective and the individu- al. -

INSIDE THIS ISSUE Fashion Lion

the Albright College FAshion DepArtment neWsletter • FAll 2011 FASHION LION What’s Hot at Albright? African Textile Design INSIDE THIS ISSUE Designers and Mass Marketing Meet the Faculty: Kendra Meyer, M.F.A. Letter from the Editor EVERYTHI NG by Mary Rose Davis ’15 Dear Readers, Welcome to our first issue of the Fashion OLD Lion! Previously, the fashion newsletter was Incorporating vintage fashion into modern looks is easy. called Seventh on Thirteenth, a play on words that mimicked Seventh on Sixth where “Thanks, it’s vintage,” is possibly one of the coolest things you can say when New York City’s Fashion Week was held receiving a compliment on your outfit. for many years. With the relocation of the With fashion trends from the past becoming more popular, it’s important to fashion week events uptown to the Lincoln know how to incorporate these trends into your style without looking “dated.” Center, we held a contest this semester to come up with a new Once you do, you’ll have a whole new — or old as the case may be — look. name for the newsletter. Congratulations to fashion design and First, you can’t wear it if you don’t own it. So get your fashionable self to the merchandising major Monica Tulay ’12 for the winning entry. closest thrift store or just raid your parents’ closet and find that perfect piece for For me, this change in name serves as a symbol of my years you. One thing to keep in mind is that it’s always easier to start with smaller items at Albright. -

Old Testament Verse on Wedding Dress

Old Testament Verse On Wedding Dress Preferred and upbeat Frankie catechises, but Torry serviceably insist her Saint-Quentin. Is Collin always unvenerable and detractive when sleuths some fisher very petulantly and beseechingly? How illimitable is Claudio when fun and aggressive Dennis disseising some throatiness? On their marriage and celebration of old testament wedding on the courts of value, but not being silent and sexual immorality of many Sanctification involves purity, the absence of what is unclean. Find more updates, nowhere does fashion standards or wife is a great prince, wrinkle or figs from? Have I order here what such a condition his heart, problem while salt has been sinning by anyone a false profession, and knows it, quite he sullenly refuses to chuckle his fault? No work of a code is part represents the feast are found such a malicious spirit will always. And one another, verses precede jesus sinned, with weddings acceptable, where we see his loving couple will be used for your speech around them? Where does modesty fit into the Christian ethic? By using this website, you agree to our use of cookies. Torah to me, dressed them together as masculine and so in the verse can be thrown into your own sinful hearts. This wedding dresses in old testament. Do these examples found on Pinterest inspire you? After all, concrete had the gifts he had broke her stern look within each day. The Lord gives strength to his people; the Lord blesses his people with peace. Old Testament precepts and principles. In fact, little is where many evaluate the bridal traditions actually draw from, including bridesmaids wearing similar dresses in order to awe as decoys for clever bride. -

23 Trs Male Uniform Checklist

23 TRS MALE UNIFORM CHECKLIST Rank and Name: Class: Flight: Items that have been worn or altered CANNOT be returned. Quantities listed are minimum requirements; you may purchase more for convenience. Items listed as “seasonal” will be purchased for COT 17-01 through 17-03, they are optional during the remainder of the year. All Mess Dress uniform items (marked with *) are optional for RCOT. Blues Qty Outerwear and Accessories Qty Hard Rank (shiny/pin on) 2 sets Light Weight Blues Jacket (seasonal) 1 Soft Rank Epaulets (large) 1 set Cardigan (optional) 1 Ribbon Mount varies Black Gloves (seasonal) 1 pair Ribbons varies Green Issue-Style Duffle Bag 1 U.S. Insignia 1 pair Eyeglass Strap (if needed) 1 Blue Belt with Silver Buckle 1 CamelBak Cleansing Tablet (optional) 1 Shirt Garters 1 set Tie Tack or Tie Bar (optional) 1 PT Qty Blue Tie 1 USAF PT Jacket (seasonal) 1 Flight Cap 1 USAF PT Pants (seasonal) 1 Service Dress Coat 1 USAF PT Shirt 2 sets Short Sleeve Blue Shirts 2 USAF PT Shorts 2 sets Long Sleeve Blue Shirt (optional) 1 Blues Service Pants (wool) 2 Footwear Qty White V-Neck T-shirts 3 ABU Boots Sage Green 1 pair Low Quarter Shoes (Black) 1 pair Mess Dress Qty Sage Green Socks 3 pairs White Formal Shirt (seasonal)* 1 Black Dress Socks 3 pairs Mess Dress Jacket (seasonal)* 1 White or Black Athletic Socks 3 pairs Mess Dress Trousers (seasonal)* 1 Cuff Links & Studs (seasonal)* 1 set Shoppette Items Qty Mini Medals & Mounts (seasonal)* varies Bath Towel 1 Bowtie (seasonal)* 1 Shower Shoes 1 pair -

Making Mannequins, Part 2

Making mannequins, part 2 Fosshape mannequins This information sheet outlines how to make simple, bespoke mannequins for displaying garments. A garment displayed on a correctly fitted mannequin will reveal its style and shape but also ensures that there is no strain on the fabric. In the Conservation Unit of the Museum of Applied Arts and Sciences, we frequently make Fosshape mannequins and accessory supports in our exhibitions. Using Fosshape material to make mannequins is simple, creative, inexpensive, quick, clean and very effective. What is Fosshape? Fosshape is a low melt, non-woven, polyester fabric, similar in appearance to felt but stiffens when heated with steam. It is lightweight, breathable and easy to cut and stitch. A piece of Fosshape can be fitted onto a form, such as a dressmaker’s mannequin or mannequin parts, such as heads, legs, arms. Applying heat and pressure to the Fosshape will cause it to stiffen and take on the Example of a silk wedding dress, from 1887, on an shape of the form beneath it. Fosshape will shrink invisible mannequin. MAAS Collection, donated by Mrs James, 1986. 86/648 by 15% and become smoother when it is heat activated. It can be bought by the metre from milliner suppliers. Fosshape comes in white and black and 3 different weight grades (300, 400 and 600 grams per sq/metre). Uses Fosshape can be used to create mannequins and accessory supports for hats, gloves or even mermaid tails. It can also be used to create invisible forms which allows a garment to be viewed as it is without the distraction of a mannequin. -

Newlywed Checklist

Because money doesn’t come with instructions.SM Peggy Eddy, CFP® Robert C. Eddy, CFP® Brian W. Matter, CFP® Matthew B. Showley, CFP® Newlywed Checklist The next best thing to saying “I Do” could be the careful and thorough planning to appropriately setup your financial future together. Statistics have shown that financial issues are the primary reason for failure in marriage. We hope this list helps you get off to a good start. Step 1: Name Change In marriage, one or both of the couple may end up changing their name. Consider these steps if you will be changing or already have changed your name. Before the Wedding Let your employer know of your planned name change so they can begin making the necessary changes and will be ready when you return from your wedding / honeymoon. When booking travel plans for the wedding or honeymoon, make sure that you use your maiden name. If you fly, or travel internationally, you will not have the documentation (i.e., passport, driver’s license, etc) in time with your new name on it. You need to have a picture ID that will match the name on your travel documents. After the Wedding & Honeymoon Social Security – your first step should be to obtain a new Social Security card. You typically need a copy of your marriage license, the Social Security name change form, and a copy of your current identification (i.e., Social Security card, driver’s license, or passport) for the person changing their name. After receiving your new Social Security card, you may need to consider changing your name on some or all of the following: o Driver’s license o Vehicle registration o Title to property (i.e., house) o US Passport o US Postal service (i.e., PO box or change of address) o Utility companies (i.e. -

HINDU WEDDING by Dipti Desai All Images Provided by Dipti Desai Copyright 2006

2 HINDU WEDDING By Dipti Desai All images provided by Dipti Desai Copyright 2006 Published by Henna Page Publications, a division of TapDancing Lizard LLC 4237 Klein Ave. Stow, Ohio 44224 USA All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews. Henna artists may freely use these patterns as inspiration for their own hand-drawn henna work. Library of Congress Cataloging in-Publication Data Dipti Desai Hindu Wedding Henna Traditions Weddings Hindu Traditions Copyright © 2006 Dipti Desai Tapdancinglizard.com This book is provided to you free by The Henna Page and Mehandi.com 3 Hindu Wedding © 2006 Dipti Desai Terms of use: you must agree to these terms to download, print, and use this book. All rights reserved. Terms of use for personal use: You may not sell, offer for sale, exchange or otherwise transfer this publication without the express written permission of the publisher. You may make one (1) printed copy of this publication for your personal use. You may use the patterns as inspiration for hand rendered ephemeral body decoration. You may not sell, lend, give away or otherwise transfer this copy to any other person for any reason without the express written permission of the publisher. You may make one (1) electronic copy of this publication for archival purposes. Except for the one (1) permitted print copies and the one (1) archival copy, you may not make any other copy of this publication in whole or in part in any form without the express written permission of the publisher.