Research Analysis of Phone Calls Regarding Fluoride Exposure Made to New Jersey Poison Control Center from 2010 to 2012

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CHEMICALS of PUBLIC HEALTH CONCERN and Their Management in the African Region

H H C Hg H N C OH O O HO OH OH CHEMICALS OF PUBLIC HEALTH CONCERN and their management in the African Region REGIONAL ASSESSMENT REPORT 4 JULY 2014 AFRO LIBRARY CATALOGUING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA Chemicals of public health concern in the African Region and their management: Regional Assessment Report 1. Chemically-Induced Disorders – prevention & control 2. Environmental Exposure 3. Polluants environnemental – adverse effects – toxicity 4. Hazardous Substances 5. Risk Management 6. Health Impact Assessment I. World Health Organization. Regional Office for Africa II.Title ISBN: 978-929023281-0 (NLM Classification:QZ 59) © WHO REGIONAL OFFICE FOR AFRICA, 2014 Publications of the World Health Organization enjoy The mention of specific companies or of certain copyright protection in accordance with the provisions manufacturers’ products does not imply that they of Protocol 2 of the Universal Copyright Convention. are endorsed or recommended by the World Health All rights reserved. Copies of this publication may be Organization in preference to others of a similar nature obtained from the Library, WHO Regional Office for that are not mentioned. Errors and omissions excepted, Africa, P.O. Box 6, Brazzaville, Republic of Congo (Tel: the names of proprietary products are distinguished by +47 241 39100; +242 06 5081114; Fax: +47 241 initial capital letters. 39501; E-mail: [email protected]). Requests for permission to reproduce or translate this publication All reasonable precautions have been taken by the – whether for sale or for non-commercial distribution – World Health Organization to verify the information should be sent to the same address. contained in this publication. -

Effect of Vitamin D on Chronic Behavioral and Dental Toxicities of Sodium Fluoride in Rats

Fluoride Vol. 36 No. 3 189-197 2003 Research Report 189 EFFECT OF VITAMIN D ON CHRONIC BEHAVIORAL AND DENTAL TOXICITIES OF SODIUM FLUORIDE IN RATS Perumal Ekambaram,a Vanaja Paulb Chennai (Madras), India SUMMARY: Adult female Wistar rats were treated daily for 60 days with so- dium fluoride (500 ppm NaF = 226 ppm fluoride ion) in drinking water, alone or in combination with vitamin D (200 IU/kg by oral intubation). Throughout the period, food intake was measured daily. Body weight gain, exploratory motor activity (EMA) rota-rod motor coordination, dental structure, brain acetylcho- linesterase (AchE) activity, and serum fluoride and serum calcium concentra- tion were determined 24 hr after the last treatment. Serum fluoride concentra- tion increased markedly in the NaF-treated animals and was accompanied by decreased food intake, reduced body weight gain, impairment of EMA and motor coordination, dental lesions, inhibition of brain AchE activity, and hy- pocalcemia. Administration of vitamin D along with NaF prevented hypocal- cemia. However, the toxic action fluoride on motor coordination, brain AchE activity, and the teeth was not prevented in these animals, probably because vitamin D is not able to decrease the level of fluoride in the serum. Therefore, vitamin D has only limited value as a protective dietary factor against chronic toxic effects of fluoride. Keywords: Dental lesions; Fluoride toxicity; Locomotor behavior; Rat toxicity; Serum calcium; Serum fluoride; Vitamin D. INTRODUCTION Fluorides are naturally occurring contaminants in the environment.1 Pro- longed ingestion of drinking water containing 1–3 ppm of fluoride ion pro- duces deleterious effects on skeletal, dental,1 and soft tissues,2,3 enzyme ac- tivities,4 and locomotor behavior5 in animals. -

I Need Your Feedback & Ideas!

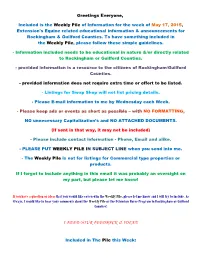

Greetings Everyone, Included is the Weekly Pile of Information for the week of May 17, 2015, Extension's Equine related educational information & announcements for Rockingham & Guilford Counties. To have something included in the Weekly Pile, please follow these simple guidelines. Information included needs to be educational in nature &/or directly related to Rockingham or Guilford Counties. provided information is a resource to the citizens of Rockingham/Guilford Counties. provided information does not require extra time or effort to be listed. Listings for Swap Shop will not list pricing details. Please Email information to me by Wednesday each Week. Please keep ads or events as short as possible – with NO FORMATTING, NO unnecessary Capitalization’s and NO ATTACHED DOCUMENTS. (If sent in that way, it may not be included) Please include contact information Phone, Email and alike. PLEASE PUT WEEKLY PILE IN SUBJECT LINE when you send into me. The Weekly Pile is not for listings for Commercial type properties or products. If I forgot to include anything in this email it was probably an oversight on my part, but please let me know! If you have a question or ideas that you would like covered in the Weekly Pile, please let me know and I will try to include. As Always, I would like to hear your comments about the Weekly Pile or the Extension Horse Program in Rockingham or Guilford Counties! I NEED YOUR FEEDBACK & IDEAS! Included in The Pile this Week: 1. TICKS, TICKS TICKS Its All About TICKS Program May 27th 7pm 2. Grazing Management 3. -

ADA Fluoridation Facts 2018

Fluoridation Facts Dedication This 2018 edition of Fluoridation Facts is dedicated to Dr. Ernest Newbrun, respected researcher, esteemed educator, inspiring mentor and tireless advocate for community water fluoridation. About Fluoridation Facts Fluoridation Facts contains answers to frequently asked questions regarding community water fluoridation. A number of these questions are responses to myths and misconceptions advanced by a small faction opposed to water fluoridation. The answers to the questions that appear in Fluoridation Facts are based on generally accepted, peer-reviewed, scientific evidence. They are offered to assist policy makers and the general public in making informed decisions. The answers are supported by over 400 credible scientific articles, as referenced within the document. It is hoped that decision makers will make sound choices based on this body of generally accepted, peer-reviewed science. Acknowledgments This publication was developed by the National Fluoridation Advisory Committee (NFAC) of the American Dental Association (ADA) Council on Advocacy for Access and Prevention (CAAP). NFAC members participating in the development of the publication included Valerie Peckosh, DMD, chair; Robert Crawford, DDS; Jay Kumar, DDS, MPH; Steven Levy, DDS, MPH; E. Angeles Martinez Mier, DDS, MSD, PhD; Howard Pollick, BDS, MPH; Brittany Seymour, DDS, MPH and Leon Stanislav, DDS. Principal CAAP staff contributions to this edition of Fluoridation Facts were made by: Jane S. McGinley, RDH, MBA, Manager, Fluoridation and Preventive Health Activities; Sharon (Sharee) R. Clough, RDH, MS Ed Manager, Preventive Health Activities and Carlos Jones, Coordinator, Action for Dental Health. Other significant staff contributors included Paul O’Connor, Senior Legislative Liaison, Department of State Government Affairs. -

Current Awareness in Clinical Toxicology Editors: Damian Ballam Msc and Allister Vale MD

Current Awareness in Clinical Toxicology Editors: Damian Ballam MSc and Allister Vale MD October 2016 CONTENTS General Toxicology 5 Metals 31 Management 14 Pesticides 32 Drugs 17 Chemical Warfare 34 Chemical Incidents & 25 Plants 35 Pollution Chemicals 26 Animals 35 CURRENT AWARENESS PAPERS OF THE MONTH The need for ICU admission in intoxicated patients: a prediction model Brandenburg R, Brinkman S, de Keizer NF, Kesecioglu J, Meulenbelt J, de Lange DW. Clin Toxicol 2016; online early: doi: 10.1080/15563650. 2016.1222616: Context Intoxicated patients are frequently admitted from the emergency room to the ICU for observational reasons. The question is whether these admissions are indeed necessary. Objective The aim of this study was to develop a model that predicts the need of ICU treatment (receiving mechanical ventilation and/or vasopressors <24 h of the ICU admission and/or in- hospital mortality). Materials and methods We performed a retrospective cohort study from a national ICU-registry, including 86 Dutch ICUs. We aimed to include only observational admissions and therefore excluded admissions with treatment, at the start of the admission that can only be applied on the ICU (mechanical Current Awareness in Clinical Toxicology is produced monthly for the American Academy of Clinical Toxicology by the Birmingham Unit of the UK National Poisons Information Service, with contributions from the Cardiff, Edinburgh, and Newcastle Units. The NPIS is commissioned by Public Health England 2 ventilation or CPR before admission). First, a generalized linear mixed-effects model with binominal link function and a random intercept per hospital was developed, based on covariates available in the first hour of ICU admission. -

ARSENIC and FLUORIDE INDUCED TOXICITY in GASTROCNEMIUS MUSCLE of MICE and ITS REVERSAL by THERAPEUTIC AGENTS NJ Chinoy,A SB Nair, DD Jhala Ahmedabad, India

Fluoride 2004;37(4):243–248 Research report 243 ARSENIC AND FLUORIDE INDUCED TOXICITY IN GASTROCNEMIUS MUSCLE OF MICE AND ITS REVERSAL BY THERAPEUTIC AGENTS NJ Chinoy,a SB Nair, DD Jhala Ahmedabad, India SUMMARY: Sodium fluoride (NaF, 5 mg/kg bw) and arsenic trioxide (As2O3, 0.05 mg/ kg bw), individually or in combination, were administered orally for 30 days to Swiss strain adult female mice (Mus musculus). Alterations in the physiology of the gastrocnemius muscle occurred with a decline in total protein levels and acetylcholinesterase activity that would affect its contractile pattern. The significantly enhanced levels of glycogen with a concomitant decrease in phosphorylase activity could alter the contraction of the quick contracting white fibres, while the decrease in activities of ATPase and succinate dehydrogenase suggests disturbance in the oxidative and energy metabolisms. Withdrawal of the NaF and/or As2O3 treatment for 30 days produced incomplete recovery. However supplementation with ascorbic acid, calcium, and vitamin E, alone or in combination, during the withdrawal period, was beneficial for recovery of the muscle parameters. These findings are important in the field of muscle physiology and kinesiology. Key words: Arsenic and muscle; Calcium phosphate; Fluoride and muscle; Gastrocnemius muscle; Mice; Toxicity reversal; Vitamin C; Vitamin E. INTRODUCTION It is now well established that ingestion of fluoride affects not only teeth and bones but also many other organs in the body. Structural and biochemical changes in several soft tissues including muscle have been reported in male and female rats and mice from different doses of fluoride.1-7 Combined arsenic/fluo- ride poisoning also occurs, especially in India, China, and Bangladesh, where both As and F are abundant in certain drinking water sources. -

Arsenic and Fluoride: Two Major Ground Water Pollutants

Indian Journal of Experimental Biology Vol. 48, July 2010, pp. 666-678 Review Article Arsenic and fluoride: Two major ground water pollutants Swapnila Chouhan & S J S Flora* Division of Pharmacology and Toxicology, Defence Research and Development Establishment, Gwalior 474 002, India Increasing human activities have modified the global cycle of heavy metals, non metals and metalloids. Both arsenic and fluoride are ubiquitous in the environment. Thousands of people are suffering from the toxic effects of arsenicals and fluorides in many countries all over the world. These two elements are recognized worldwide as the most serious inorganic contaminants in drinking water. Many studies have reported as regards to simple fluorosis and arsenicosis, but the knowledge of the joint action of these two elements is lacking and the results derived from previous studies were inconclusive. Contradictory results were reported in experimental studies in which different joint actions such as independent, synergistic and antagonistic effects were observed. This indicates that interaction mechanism of these two elements is considerable complicated and requires extensive studies. When two different types of toxicants are simultaneously going inside a human body they may function independently or can act as synergistic or antagonistic to one another. Thus there is an urge to resolve the question that how arsenic and fluoride act in condition of concomitant exposure. Although there have been reports in literature of individual toxicity of arsenic and fluoride however, there is very little known about the effects following the combined exposure to these toxicants. This review focused on recent developments in the research on the condition of individual exposure to arsenic and fluoride along with the recent updates of their combined exposure to better understand the joint action of these two toxicants. -

Risk Assessment of Trace Element Contamination in Drinking Water

Hindawi Journal of Chemistry Volume 2021, Article ID 6627254, 10 pages https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/6627254 Research Article Risk Assessment of Trace Element Contamination in Drinking Water and Agricultural Soil: A Study in Selected Chronic Kidney Disease of Unknown Etiology (CKDu) Endemic Areas in Sri Lanka W. P. R. T. Perera ,1 M. D. N. R. Dayananda ,1 D. M. U. C. Dissanayake,1 R. A. S. D. Rathnasekara,1 W. S. M. Botheju,1 J. A. Liyanage ,1 S. K. Weragoda,2 and K. A. M. Kularathne2 1Department of Chemistry, Faculty of Science, University of Kelaniya, Kelaniya, Sri Lanka 2National Water Supply and Drainage Board, Katugastota 20800, Sri Lanka Correspondence should be addressed to W. P. R. T. Perera; [email protected] Received 2 December 2020; Revised 14 January 2021; Accepted 20 January 2021; Published 29 January 2021 Academic Editor: Zenilda Cardeal Copyright © 2021 W. P. R. T. Perera et al. *is is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Unexplained or unclear etiology of chronic kidney disease (CKDu) has been reported in Sri Lanka’s North Central Province (NCP) for more than two decades. Meanwhile, high exposure to heavy metals/metalloids and their accumulation are recognized as the origin of many acute and chronic diseases in certain vulnerable human tissues including kidneys. *is study evaluates the contamination status of heavy metals/metalloids of the drinking water and agricultural soil in two CKDu endemic areas compared with a reference area in Sri Lanka based on common indexes and attribute of the commonly used fertilizers evaluated to identify the basic sources of toxic metals in the agricultural soil. -

Amelioration of Fluoride Toxicity by Vitamins E and D in Reproductive

Digital Archive of Fluoride Journal © 2007 ISFR www.FluorideResearch.org Fluoride Vol. 31 No. 4 203-216 1998. Research Report 203 AMELIORATION OF FLUORIDE TOXICITY BY VITAMINS E AND D IN REPRODUCTIVE FUNCTIONS OF MALE MICE N Chinoy and Arti Sharma Ahmedabad, India SUMMARY: Studies on the beneficial effects of vitamins E and D supplementation on functions of caput and cauda epididymides, their spermatozoa, vas deferens and seminal vesicle of sodium fluoride (NaF) treated (10 mg/kg body weight) male mice (Mus musculus) were carried out. The NaF treatment resulted in significant decrease in the body and epididymis weight but those of vas deferens and seminal vesicle were not affected. NaF treatment brought about alterations in epididymal milieu as elucidated by the significant decrease in levels of sialic acid and protein as well as activity of ATPase in epididymides. As a result, the sperm maturation process was affected leading to a significant decline in cauda epididymal sperm motility and viability. This caused a significant reduction in fertility rate. The cauda epididymal sperm count was also significantly reduced. The data obtained suggest that fluoride treatment induced significant metabolic alterations in the epididymides, vas deferens and seminal vesicles of mice. The withdrawal of NaF treatment (30 days) produced incomplete recovery. On the other hand, sup-plementation of vitamins E or D during the withdrawal period of NaF treated mice was found to be very beneficial in recovery of all NaF induced effects, thus elucidating their ameliorative role in recovery from toxic effects of NaF on the reproductive functions and fertility. On the whole, a combination of vitamins E and D treatment was comparatively more effective than that with vitamin E or D alone. -

Fluoride in Drinking-Water

WHO/SDE/WSH/03.04/96 English only Fluoride in Drinking-water Background document for development of WHO Guidelines for Drinking-water Quality © World Health Organization 2004 Requests for permission to reproduce or translate WHO publications - whether for sale of for non- commercial distribution - should be addressed to Publications (Fax: +41 22 791 4806; e-mail: [email protected]. The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the World Health Organization concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The mention of specific companies or of certain manufacturers' products does not imply that they are endorsed or recommended by the World Health Organization in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. Errors and omissions excepted, the names of proprietary products are distinguished by initial capital letters. The World Health Organization does not warrant that the information contained in this publication is complete and correct and shall not be liable for any damage incurred as a results of its use. Preface One of the primary goals of WHO and its member states is that “all people, whatever their stage of development and their social and economic conditions, have the right to have access to an adequate supply of safe drinking water.” A major WHO function to achieve such goals is the responsibility “to propose ... regulations, and to make recommendations with respect to international health matters ....” The first WHO document dealing specifically with public drinking-water quality was published in 1958 as International Standards for Drinking-water. -

Sulfuryl Fluoride Interim AEGL Document

1 2 3 4 ACUTE EXPOSURE GUIDELINE LEVELS (AEGLs) 5 FOR 6 SULFURYL FLUORIDE 7 2699-79-8 8 9 SO2F2 10 11 12 13 14 INTERIM 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 SULFURYL FLUORIDE INTERIM:06/2008 1 2 ACUTE EXPOSURE GUIDELINE LEVELS (AEGLs) 3 FOR 4 SULFURYL FLUORIDE 5 2699-79-8 6 7 8 9 INTERIM 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 2 SULFURYL FLUORIDE INTERIM:06/2008 1 2 PREFACE 3 4 Under the authority of the Federal Advisory Committee Act (FACA) P. L. 92-463 of 5 1972, the National Advisory Committee for Acute Exposure Guideline Levels for Hazardous 6 Substances (NAC/AEGL Committee) has been established to identify, review and interpret 7 relevant toxicologic and other scientific data and develop AEGLs for high priority, acutely toxic 8 chemicals. 9 10 AEGLs represent threshold exposure limits for the general public and are applicable to 11 emergency exposure periods ranging from 10 minutes to 8 hours. Three levels C AEGL-1, 12 AEGL-2 and AEGL-3 C are developed for each of five exposure periods (10 and 30 minutes, 1 13 hour, 4 hours, and 8 hours) and are distinguished by varying degrees of severity of toxic effects. 14 The three AEGLs are defined as follows: 15 16 AEGL-1 is the airborne concentration (expressed as parts per million or milligrams per 17 cubic meter [ppm or mg/m3]) of a substance above which it is predicted that the general 18 population, including susceptible individuals, could experience notable discomfort, irritation, or 19 certain asymptomatic, non-sensory effects. -

Surveillance Index – 2008

Surveillance index – 2008 A B otitis 35(2), 36; paraneoplastic skin disease 35(2), 33; sarcoid 35(4), 15; Abalone viral ganglioneuritis ruled out Bacterial gill disease, salmon 35(2), 36 tritrichomonas 35(1), 14 35(3), 21 Bee mites investigated 35(1), 22 Abomasitis, cattle 35(3), 17 Beehive risk goods investigated 35(2), 38 Cattle, acorn toxicity 35(3), 17, 20; Abortion, cattle 35(3), 16; 35(3), 20; fungal, Bees, honey bee exotic disease surveillance adenoviral abomasitis 35(3), 17; cattle 35(3), 16, 18; equine 35(3), 21; report 35(3), 13 adenoviral pneumonia 35(4), 13; hairy shaker, sheep 35(4), 14; listerial, Bellbirds, malarial parasite 35(4), 15 Arcanobacteria pyogenes abortion 35(3), sheep 35(3), 18; macrocarpa, cattle Biosecurity risk pathways in the commercial 20; ataxia 35(3), 17; blue-green algae 35(3), 20; Mortierella wolfii, cattle poultry industry: free-range layers, pullet- toxicosis 35(2), 32; bovine enzootic 35(3), 16; Neospora, cattle 35(3), 16; rearers and turkey broilers 35(4), 4 pneumonia 35(1), 14; BVD 35(2), Salmonella Typhimurium 35(3), 16; Biosecurity Surveillance Strategy 35(3), 3 32; carbohydrate overload 35(1), sheep, investigated 35(3), 21 Birds, Biosecurity risk pathways in the 14; coccidiosis 35(2), 33; copper Acorn toxicity, cattle 35(3), 17; 35(3), 20 commercial poultry industry: free-range poisoning 35(1), 11; 35(3), 16, 20; Adenoviral abomasitis, cattle 35(3), 17 layers, pullet-rearers and turkey broilers 35(4), 11; 13; cyanide toxicity 35(3), Adenoviral pneumonia, cattle 35(4), 13 35(4), 4; histomoniasis,