Prophet River First Nation Book of Authorities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dionisio Point Excavations

1HE• Publication of the Archaeological Society of Vol. 31 , No. I - 1999 Dionisio Point Excavations ARCHAEOLOGICAL SOCIETY OF &MIDDEN BRITISH COLUMBIA Published four times a year by the Archaeological Society of British Columbia Dedicated to the protection of archaeological resot:Jrces and the spread of archaeological knowledge. Editorial Committee Editor: Heather Myles (274-4294) President Field Editor: Richard Brolly (689-1678) Helmi Braches (462-8942) arcas@istar. ca [email protected] News Editor: Heather Myles Publications Editor: Robbin Chatan (215-1746) Membership [email protected] Sean Nugent (685-9592) Assistant Editors: Erin Strutt [email protected] erins@intergate. be.ca Fred Braches Annual membership includes I year's subscription to [email protected] The Midden and the ASBC newsletter, SocNotes. Production & Subscriptions: Fred Braches ( 462-8942) Membership Fees I SuBSCRIPTION is included with ASBC membership. Individual: $25 Family: $30 . Seniors/Students: $I 8 Non-members: $14.50 per year ($1 7.00 USA and overseas), Send cheque or money order payable to the ASBC to: payable in Canadian funds to the ASBC. Remit to: ASBC Memberships Midden Subscriptions, ASBC P.O. Box 520, Bentall Station P.O. Box 520, Bentall Station Vancouver BC V6C 2N3 Vancouver BC V6C 2N3 SuBMISSIONs: We welcome contributions on subjects germane ASBC on Internet to BC archaeology. Guidelines are available on request. Sub http://home.istar.ca/-glenchan/asbc/asbc.shtml missions and exchange publications should be directed to the appropriate editor at the ASBC address. Affiliated Chapters Copyright Nanaimo Contact: Rachael Sydenham Internet: http://www.geocities.com/rainforest/5433 Contents of The Midden are copyrighted by the ASBC. -

Bc12 Report.Pdf

Soils of the Fort Nelson Area of British Columbia K.W. G. VALENTINE Canada Department of Agriculture, Vancouver, B.C. REPORT No. 12 British Columbia Soi1 Survey Research Branch - Canada Department of Agriculture. 1971 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The author wishes to acknowledge the help of Mr. L. Farstad, Canada Depart- ment of Agriculture, Vancouver, and Mr. P. N. Sprout, British Columbia Depart- ment of Agriculture, Kelowna, who initiated the project and gave constructive advice during various parts of the field and office work. Mr. D. Hodgson helped with the field work in the summer of 1967. Soi1 analyses were carried out by Mr. S. K. Chan and Miss M. E. Turnbull. Mr. J. M. Wallace, Department of Energy, Mines, and Resources, Water Resources Branch, Vancouver, B.C., provided valuable information on the seasonal flood levels of the Muskwa and Fort Nelson rivers., Mr. R. A. Nemeth, pipeline engineer, Westcoast Transmission CO. Ltd., Van- couver, gave permission for information from his company’s Yoyo pipeline muskeg survey to be used in Fig. 5. Dr. H. Vaartnou, Research Station, Canada Department of Agriculture, Beaverlodge, Alta., identified many of the plant specimens that were collected during the survey. Mr. G. W. Robertson, Agrometeorology Section, Canada Department of Agri- culture, Ottawa, supplied estimates of agroclimatic normals based on the Hopkins regression formulas. Mr. R. Marshall, Agroclimatology, British Columbia Depart- ment of Agriculture, also supplied much climatic data. The soi1 map and Fig. l-5, 11, 13, 15, and 16 were prepared by the Cartogra- phy Section, Soi1 Research Institute, Canada Department of Agriculture, Ottawa. Messrs. -

Quarterly Report on Short-Term Water Approvals and Use

Quarterly Report on Short-Term Water Approvals and Use April to June 2011 About the BC Oil and Gas Commission The BC Oil and Gas Commission is an independent, single-window regulatory agency with responsibilities for overseeing oil and gas operations in British Columbia, including exploration, development, pipeline transportation and reclamation. The Commission’s core roles include reviewing and assessing applications for industry activity, consulting with First Nations, ensuring industry complies with provincial legislation and cooperating with partner agencies. The public interest is protected through the objectives of ensuring public safety, protecting the environment, conserving petroleum resources and ensuring equitable participation in production. TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction Page 2 Processes and Requirements Page 3 Results Page 4 Summary Page 7 Appendix A Page 8 Appendix B Page 9 Appendix C Page 12 1 BC Oil and Gas Commission Quarterly Report on Short-Term Water Approvals and Use Introduction The Oil and Gas Activities Act (OGAA) provides authority to the BC Oil and Gas Commission (Commission) to issue short-term water use approvals under Section 8 of the Water Act to manage short-term water use by the oil and gas industry. Approvals under Section 8 of the Water Act authorize the diversion and use of water for a term not exceeding 12 months. This report details the Commission’s responsibilities and authorities under Section 8 of the Water Act; it does not include the diversion and use of water approved by other agencies (such as the Ministry of Forests, Lands and Natural Resource Operations, which has responsibility for water licensing) or for purposes other than oil and gas activities. -

Volume 5 Appendix A21 Part 1 Community Summary: Prophet River First Nation

SITE C CLEAN ENERGY PROJECT VOLUME 5 APPENDIX A21 PART 1 COMMUNITY SUMMARY: PROPHET RIVER FIRST NATION FINAL REPORT Prepared for: BC Hydro Power and Authority 333 Dunsmuir Street Vancouver, B.C. V6B 5R3 Prepared by: Fasken Martineau 2900-550 Burrard Street Vancouver, B.C. V6C 0A3 January 2013 Site C Clean Energy Project Volume 5 Appendix A21 Part 1 Community Summary: Prophet River First Nation Prophet River First Nation Prophet River First Nation (PRFN), also known as Dene Tsaa First Nation, has one reserve, Prophet River No. 4, with an area of 373.9 ha.1 The reserve is located approximately 100 km south of Fort Nelson on Highway 97.2 According to Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada, as of December 2012, PRFN has a registered population of 260, with 103 members living on PRFN’s reserve.3 PRFN has a Chief and two Councillors, and uses a custom electoral system.4 The PRFN’s economic activities include a restaurant and commercial services, camps, and catering.5 PRFN is a member of the Treaty 8 Tribal Association and the Council of BC Treaty 8 Chiefs.6 Historical Background Members of PRFN speak Dunne-zaa (Beaver), part of the Athapaskan linguistic group.7 Some relatives of present-day PRFN peoples adhered to Treaty 8 on August 15, 1910, and the rest adhered on August 4, 1911.8 PRFN peoples were joined with the Fort Nelson Slave Band between 1957 and 1974. PRFN was created when it split away from the Fort Nelson Band in 1974.9 Traditional Territory PRFN’s traditional lands cover approximately 25,000 km² from the Rocky Mountains to the 10 boreal forest east of the Prophet River. -

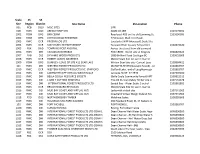

Scale Site SS Region SS District Site Name SS Location Phone

Scale SS SS Site Region District Site Name SS Location Phone 001 RCB DQU MISC SITES SIFR 01B RWC DQC ABFAM TEMP SITE SAME AS 1BB 2505574201 1001 ROM DPG BKB CEDAR Road past 4G3 on the old Lamming Ce 2505690096 1002 ROM DPG JOHN DUNCAN RESIDENCE 7750 Lower Mud river Road. 1003 RWC DCR PROBYN LOG LTD. Located at WFP Menzies#1 Scale Site 1004 RWC DCR MATCHLEE LTD PARTNERSHIP Tsowwin River estuary Tahsis Inlet 2502872120 1005 RSK DND TOMPKINS POST AND RAIL Across the street from old corwood 1006 RWC DNI CANADIAN OVERSEAS FOG CREEK - North side of King Isla 6046820425 1007 RKB DSE DYNAMIC WOOD PRODUCTS 1839 Brilliant Road Castlegar BC 2503653669 1008 RWC DCR ROBERT (ANDY) ANDERSEN Mobile Scale Site for use in marine 1009 ROM DPG DUNKLEY- LEASE OF SITE 411 BEAR LAKE Winton Bear lake site- Current Leas 2509984421 101 RWC DNI WESTERN FOREST PRODUCTS INC. MAHATTA RIVER (Quatsino Sound) - Lo 2502863767 1010 RWC DCR WESTERN FOREST PRODUCTS INC. STAFFORD Stafford Lake , end of Loughborough 2502863767 1011 RWC DSI LADYSMITH WFP VIRTUAL WEIGH SCALE Latitude 48 59' 57.79"N 2507204200 1012 RWC DNI BELLA COOLA RESOURCE SOCIETY (Bella Coola Community Forest) VIRT 2509822515 1013 RWC DSI L AND Y CUTTING EDGE MILL The old Duncan Valley Timber site o 2507151678 1014 RWC DNI INTERNATIONAL FOREST PRODUCTS LTD Sandal Bay - Water Scale. 2 out of 2502861881 1015 RWC DCR BRUCE EDWARD REYNOLDS Mobile Scale Site for use in marine 1016 RWC DSI MUD BAY COASTLAND VIRTUAL W/S Ladysmith virtual site 2507541962 1017 RWC DSI MUD BAY COASTLAND VIRTUAL W/S Coastland Virtual Weigh Scale at Mu 2507541962 1018 RTO DOS NORTH ENDERBY TIMBER Malakwa Scales 2508389668 1019 RWC DSI HAULBACK MILLYARD GALIANO 200 Haulback Road, DL 14 Galiano Is 102 RWC DNI PORT MCNEILL PORT MCNEILL 2502863767 1020 RWC DSI KURUCZ ROVING Roving, Port Alberni area 1021 RWC DNI INTERNATIONAL FOREST PRODUCTS LTD-DEAN 1 Dean Channel Heli Water Scale. -

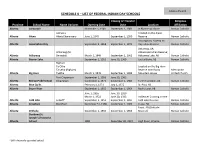

Schedule K – List of Federal Indian Day Schools

SCHEDULE K – LIST OF FEDERAL INDIAN DAY SCHOOLS Closing or Transfer Religious Province School Name Name Variants Opening Date Date Location Affiliation Alberta Alexander November 1, 1949 September 1, 1981 In Riviere qui Barre Roman Catholic Glenevis Located on the Alexis Alberta Alexis Alexis Elementary June 1, 1949 September 1, 1990 Reserve Roman Catholic Assumption, Alberta on Alberta Assumption Day September 9, 1968 September 1, 1971 Hay Lakes Reserve Roman Catholic Atikameg, AB; Atikameg (St. Atikamisie Indian Reserve; Alberta Atikameg Benedict) March 1, 1949 September 1, 1962 Atikameg Lake, AB Roman Catholic Alberta Beaver Lake September 1, 1952 June 30, 1960 Lac La Biche, AB Roman Catholic Bighorn Ta Otha Located on the Big Horn Ta Otha (Bighorn) Reserve near Rocky Mennonite Alberta Big Horn Taotha March 1, 1949 September 1, 1989 Mountain House United Church Fort Chipewyan September 1, 1956 June 30, 1963 Alberta Bishop Piché School Chipewyan September 1, 1971 September 1, 1985 Fort Chipewyan, AB Roman Catholic Alberta Blue Quills February 1, 1971 July 1, 1972 St. Paul, AB Alberta Boyer River September 1, 1955 September 1, 1964 Rocky Lane, AB Roman Catholic June 1, 1916 June 30, 1920 March 1, 1922 June 30, 1933 At Beaver Crossing on the Alberta Cold Lake LeGoff1 September 1, 1953 September 1, 1997 Cold Lake Reserve Roman Catholic Alberta Crowfoot Blackfoot December 31, 1968 September 1, 1989 Cluny, AB Roman Catholic Faust, AB (Driftpile Alberta Driftpile September 1, 1955 September 1, 1964 Reserve) Roman Catholic Dunbow (St. Joseph’s) Industrial Alberta School 1884 December 30, 1922 High River, Alberta Roman Catholic 1 Still a federally-operated school. -

Rangifer Tarandus Caribou) in BRITISH COLUMBIA

THE EARLY HISTORY OF WOODLAND CARIBOU (Rangifer tarandus caribou) IN BRITISH COLUMBIA by David J. Spalding Wildlife Bulletin No. B-100 March 2000 THE EARLY HISTORY OF WOODLAND CARIBOU (Rangifer tarandus caribou) IN BRITISH COLUMBIA by David J. Spalding Ministry of Environment, Lands and Parks Wildlife Branch Victoria BC Wildlife Bulletin No. B-100 March 2000 “Wildlife Bulletins frequently contain preliminary data, so conclusions based on these may be sub- ject to change. Bulletins receive some review and may be cited in publications. Copies may be obtained, depending upon supply, from the Ministry of Environment, Lands and Parks, Wildlife Branch, P.O. Box 9374 Stn Prov Gov, Victoria, BC V8W 9M4.” © Province of British Columbia 2000 Canadian Cataloguing in Publication Data Spalding, D. J. The early history of woodland caribou (Rangifer tarandus caribou) in British Columbia (Wildlife bulletin ; no. B-100) Includes bibliographical references : p. 60 ISBN 0-7726-4167-6 1. Woodland caribou - British Columbia. 2. Woodland caribou - Habitat - British Columbia. I. British Columbia. Wildlife Branch. II. Title. III. Series: Wildlife bulletin (British Columbia. Wildlife Branch) ; no. B-100 QL737.U55S62 2000 333.95’9658’09711 C00-960085-X Citation: Spalding, D.J. 2000. The Early History of Woodland Caribou (Rangifer tarandus caribou) in British Columbia. B.C. Minist. Environ., Lands and Parks, Wildl. Branch, Victoria, BC. Wildl. Bull. No. 100. 61pp. ii DISCLAIMER The views expressed herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent those of the B.C. Ministry of Environment, Lands and Parks. In cases where a Wildlife Bulletin is also a species’ status report, it may contain a recommended status for the species by the author. -

Annualreport1971.Pdf

PROVINCE OF BRITISH COLUMBIA DEPARTMENT OP RECREATION AND CONSERVATION HON, \V. K. K1J?.RNAN, h1inistcr Ll.OYD BROOKS, Aclit1$ t>cplil)' /.1itlisltr REPORT OF THE Department of Recreation and Conservation containing Jht rtp(Jrts of tire GENERAL ADMINISTRATION, FISH AND WILDLIFE BRANCH, PROVINCIAL PARKS BRANCH, BRITISH COLUMBIA PROVINCIAL MUSEUM, At"-'D COMMERCIAL FISHERIES BRANCH Year E11ded December 3/ 1971 Printed by K. ~1. ~iAC()ON.1.U>, Priri;cr to O>C Ql,:ecn'&bf<»t Ex«elknt ~taje.sty lA ri.&ht or the PrcwiNe of British Columbia. 1'72 \ VICTORIA, BRITISH COLUMBIA, JUN!! 30, 1972 To Colonel tire llonourable JOHN R. NICHOLSON, P.C., O.B.E., Q.C., LL.D., Lieutenam-Govemor of tire Province of British Columbia. MAY IT PLEASE YOUR HONOUR: Herewith I beg respectfully to submit the Annual Report of the Department of Recreation and Conservation for the year ended December 31, 1971. W. K. KIERNAN MiniSter of Recreation and Conservation VICTORIA, BRITISH COLllMllIA, JUNE 29, 1972 The Ho11011rable W. K. Kiema11, Mi11ister of Recreatio11 aml Conservation. Sm: I have the honour to submit the Annual Report of the Department of Recreation and Conservation for the year ended December 31, 1971. LLOYD BROOKS Acti11g Depwy Mi11ister of Recreation a11d Conservation CONTENTS ,_ Introduction by the Acting Deputy Minister of Recreation and Conservation General Administration 9 Fish and Wildlife Branch 15 Provincial Parks Branch 63 . -----------------·------ British Columbia Provincial Museum 97 Commercial Fisheries Branch 125 I ") I ! I l.I. I li.•l Report of the Department of Recreation and Conservation, 1971 LLOYD BROOKS, ACTll<O DBPUTY MINISTER ANO CoMMISSIONER OF FISHERlllS Th"TRODUCTIO ' The increased emphasis on 311 in1egxatcd approach 10 resources management throughout the Province, and the general concern over environmental quality by citizens, by industry, and by related resource agencies, Federal nod Provincial, bas added a new and demanding dimension to the work o( this Department. -

Peace Region Aerial Surveys, March 2004

Peace Region Aerial Surveys March 2004 Gathto Creek (Photo by Graham Suther) Prepared by: Janice Anderson, M.Sc. and Joelle Scheck, M.Sc., R.P.Bio Ecosystem Biologists, Peace Region Ministry of Water, Land & Air Protection March 2004 ABSTRACT This report summarizes the results of aerial surveys conducted within the Peace Region by Ecosystem staff from the Ministry of Water, Land and Air Protection (MWLAP). To complete a late-winter reconnaissance-level wildlife inventory and habitat assessment, 77 areas of interest were identified for survey in the Peace and Fort Nelson Forest Districts (FD). Overview flights were completed during 6 days in late March 2004 within 27 draft and 31 potential Ungulate Winter Ranges (UWRs), 8 existing Wildlife Habitat Areas (WHAs), 6 sites identified by the Oil and Gas Commission for future Coalbed Methane (CBM) exploration, and 5 additional areas of interest. Animal sightings, evidence of use by wildlife, and associated habitat descriptions and conditions were recorded for each area of interest. A total distance of 3,621 km was searched over approximately 31 survey hours in the 2004 aerial survey. A total of 6,481 ungulates, 10 canids including wolves (Canis lupus) and coyotes (Canis latrans) and 101 other incidental sightings (primarily horses) were noted during the 6 survey routes. Overall ungulate counts per species ranged from 5 bighorn sheep (Ovis canadensis) to 4,703 elk (Cervus elaphus). The total number of animals observed along each survey route ranged from 18 on March 24 (Day 4) to 3,191 on March 25 (Day 6). No animals were observed within 30 areas of interest. -

A History of Fish in the Northeastern British Columbia

HISTORICAL FISHERIES INFORMATION FROM THE MUSKWA-KECHIKA MANAGEMENT AREA Prepared By: Alicia Woods SS#2 Site 13 Comp 17 Fort St. John, BC V1J 4M7 For: Fisheries Branch Ministry of Environment, Lands and Parks Rm. 400 10003-110th Avenue Fort St. John, BC V1J 6M7 January 2001 Muskwa-Kechika Historical Fisheries Research Project SUMMARY The primary purpose of this research project was to compile and preserve historical fisheries information within the Muskwa-Kechika Management Area. This report outlines and describes, by watershed, fisheries related activities that took place over the past decades. Information gathered for this project came from personal interviews and other research. Interviews were conducted with persons from Fort St. John, Fort Nelson, Dawson Creek and other communities. The expectation of this project is to document and preserve information, that would otherwise be lost, and make it accessible for further research. In addition to preserving the past, this research will be able to provide a different outlook on past fisheries issues, and possibly bring forth new ideas and management strategies. Funding for this project was obtained through an application from BC Environment, Fisheries Section, Fort St. John, to the Muskwa-Kechika Trust Fund. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Much appreciation and thanks to Nick Baccante, for direction and knowledge on this project, Paul Mitchell-Banks for his knowledge and including me on his many excursions, the Fish and Wildlife staff at the Ministry of Environment, Lands and Parks, and Rob Woods for his immeasurable amount of knowledge of the area. The author also wishes to acknowledge the Guide Outfitters of northeastern British Columbia, Fort Nelson First Nations Band, Prophet River First Nations Band and the many locals that volunteered their time and offered their knowledge to this project. -

Chapter 4 Seasonal Weather and Local Effects

BC-E 11/12/05 11:28 PM Page 75 LAKP-British Columbia 75 Chapter 4 Seasonal Weather and Local Effects Introduction 10,000 FT 7000 FT 5000 FT 3000 FT 2000 FT 1500 FT 1000 FT WATSON LAKE 600 FT 300 FT DEASE LAKE 0 SEA LEVEL FORT NELSON WARE INGENIKA MASSET PRINCE RUPERT TERRACE SANDSPIT SMITHERS FORT ST JOHN MACKENZIE BELLA BELLA PRINCE GEORGE PORT HARDY PUNTZI MOUNTAIN WILLAMS LAKE VALEMOUNT CAMPBELL RIVER COMOX TOFINO KAMLOOPS GOLDEN LYTTON NANAIMO VERNON KELOWNA FAIRMONT VICTORIA PENTICTON CASTLEGAR CRANBROOK Map 4-1 - Topography of GFACN31 Domain This chapter is devoted to local weather hazards and effects observed in the GFACN31 area of responsibility. After extensive discussions with weather forecasters, FSS personnel, pilots and dispatchers, the most common and verifiable hazards are listed. BC-E 11/12/05 11:28 PM Page 76 76 CHAPTER FOUR Most weather hazards are described in symbols on the many maps along with a brief textual description located beneath it. In other cases, the weather phenomena are better described in words. Table 3 (page 74 and 207) provides a legend for the various symbols used throughout the local weather sections. South Coast 10,000 FT 7000 FT 5000 FT 3000 FT PORT HARDY 2000 FT 1500 FT 1000 FT 600 FT 300 FT 0 SEA LEVEL CAMPBELL RIVER COMOX PEMBERTON TOFINO VANCOUVER HOPE NANAIMO ABBOTSFORD VICTORIA Map 4-2 - South Coast For most of the year, the winds over the South Coast of BC are predominately from the southwest to west. During the summer, however, the Pacific High builds north- ward over the offshore waters altering the winds to more of a north to northwest flow. -

Grizzly Bear DNA Inventory of the Prophet River Territory, Northeastern British Columbia

GRIZZLY BEAR INVENTORY OF THE PROPHET RIVER AREA, NORTHEASTERN BRITISH COLUMBIA Submitted to: Prophet River Indian Band Dene Tsaa First Nation Box 3250, Fort Nelson, BC V0C 1R0 Canadian Forest Products Ltd. Chetwynd Division P.O. Box 180, Chetwynd, BC V0C 1J0 B.C. Ministry of Environment, Lands and Parks Fish and Wildlife Branch, Peace Subregion Rm 400, 10003 110th Street, Fort St. John, BC V1J 6M7 Prepared by: K. G. Poole, G. Mowat, and D. A. Fear Timberland Consultants Ltd. Fish and Wildlife Division P. O. Box 171 (2620 Granite Rd.) Nelson, BC V1L 5P9 Tele.: (250) 354-3880 e-mail: [email protected] December 1999 Prophet River Wildlife Inventory Report No. 10 Prophet River grizzly bear inventory ii ABSTRACT Current harvest management of grizzly bears (Ursus arctos) in British Columbia (B.C.) is based primarily on modeling of habitat capability/suitability. No research has been conducted in the northern half of the province to verify these habitat-based estimates. In reaction to concerns from First Nation peoples, outfitters and government managers about grizzly bear population size in northeastern B.C., a DNA-based mark-recapture inventory was conducted in the Prophet River area. The study area covered 8,527 km2, and stretched from the continental divide of the northern Rocky Mountains in the west to the boreal plains in the east. The area included the Northern Boreal Mountains and Taiga Plains ecoprovinces, and the Alpine Tundra, Spruce- Willow-Birch, and Boreal White and Black Spruce biogeoclimatic zones. Fieldwork was conducted between 25 May and 1 August 1998 using a helicopter and a truck with an all terrain vehicle.