Non-Timber Forest Products (NTFP) Review for the Invermere TSA

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sporeprint, Spring 2015

LONG ISLAND MYCOLOGICAL CLUB http://limyco.org Available in full color on our website VOLUME 23, NUMBER 1, SPRING, 2015 FINDINGS AFIELD THE SEASON’S BOUNTY: 2015 Once again, Morels eluded us completely, so we have now failed to find any Black Morels at our usual collecting spot since 2011, and only a few singleton Yellow Morels that popped up here and there, except for one lucky member of the public who found thirty in Freeport under an old Cherry tree. We may have to ven- ture off-island in the future if we wish to collect Morels. Foray chair Dennis Aita of the NY Mycological Society informed me that their Morel season was lackluster, but there were oases of plenty, as wit- nessed by our webmaster Dale’s unexpected bonanza of Yellow Mo- rels on May 17 in Ulster County.(See LI Sporeprint Summer 2014.) Mean temperatures were below normal Jan thru March, and the Hygrophorus amygdalinus consequent slow soil warming delayed Spring fruiting of Morels somewhat. Will this year’s deep freeze, with the coldest February in Regular readers of this column eighty years, cause an even more pronounced delay or will the insu- might find it odd to find this one de- lating effect of deep snow cover ameliorate this process? It’s any- voted to a species which we have been one’s guess. collecting for some years, rather than Overall, last year was a consider- a newly encountered one. While Hy- able improvement over 2013, when dry grophorus amygdalinus (sometimes conditions forced us to cancel 18 forays; under a different name) is familiar to only 9, half as many, were cancelled in many of us as the small gray, almond 2014 due to lack of fungi. -

Mushrumors the Newsletter of the Northwest Mushroomers Association Volume 20 Issue 3 September - November 2009

MushRumors The Newsletter of the Northwest Mushroomers Association Volume 20 Issue 3 September - November 2009 2009 Mushroom Season Blasts into October with a Flourish A Surprising Turnout at the Annual Fall Show by Our Fungal Friends, and a Visit by David Arora Highlighted this Extraordinary Year for the Northwest Mushroomers On the heels of a year where the weather in Northwest Washington could be described as anything but nor- mal, to the surprise of many, include yours truly, it was actually a good year for mushrooms and the Northwest Mushroomers Association shined again at our traditional fall exhibit. The members, as well as the mushrooms, rose to the occasion, despite brutal conditions for collecting which included a sideways driving rain (which we photo by Pam Anderson thought had come too late), and even a thunderstorm, as we prepared to gather for the greatly anticipated sorting of our catch at the hallowed Bloedel Donovan Community Building. I wondered, not without some trepidation, about what fungi would actually show up for this years’ event. Buck McAdoo, Dick Morrison, and I had spent several harrowing hours some- what lost in the woods off the South Pass Road in a torrential downpour, all the while being filmed for posterity by Buck’s step-son, Travis, a videographer creating a documentary about mushrooming. I had to wonder about the resolve of our mem- bers to go forth in such conditions in or- In This Issue: Fabulous first impressions: Marjorie Hooks der to find the mush- David Arora Visits Bellingham crafted another artwork for the centerpiece. -

November 2014

MushRumors The Newsletter of the Northwest Mushroomers Association Volume 25, Issue 4 December 2014 After Arid Start, 2014 Mushroom Season Flourishes It All Came Together By Chuck Nafziger It all came together for the 2014 Wild Mushroom Show; an October with the perfect amount of rain for abundant mushrooms, an enthusiastic volunteer base, a Photo by Vince Biciunas great show publicity team, a warm sunny show day, and an increased public interest in foraging. Nadine Lihach, who took care of the admissions, reports that we blew away last year's record attendance by about 140 people. Add to that all the volunteers who put the show together, and we had well over 900 people involved. That's a huge event for our club. Nadine said, "... this was a record year at the entry gate: 862 attendees (includes children). Our previous high was in 2013: 723 attendees. Success is more measured in the happiness index of those attending, and many people stopped by on their way out to thank us for the wonderful show. Kids—and there were many—were especially delighted, and I'm sure there were some future mycophiles and mycologists in Sunday's crowd. The mushroom display A stunning entry display greets visitors arriving at the show. by the door was effective, as always, at luring people in. You could actually see the kids' eyes getting bigger as they surveyed the weird mushrooms, and twice during the day kids ran back to our table to tell us that they had spotted the mushroom fairy. There were many repeat adult visitors, too, often bearing mushrooms for identification. -

Mushrooms of Southwestern BC Latin Name Comment Habitat Edibility

Mushrooms of Southwestern BC Latin name Comment Habitat Edibility L S 13 12 11 10 9 8 6 5 4 3 90 Abortiporus biennis Blushing rosette On ground from buried hardwood Unknown O06 O V Agaricus albolutescens Amber-staining Agaricus On ground in woods Choice, disagrees with some D06 N N Agaricus arvensis Horse mushroom In grassy places Choice, disagrees with some D06 N F FV V FV V V N Agaricus augustus The prince Under trees in disturbed soil Choice, disagrees with some D06 N V FV FV FV FV V V V FV N Agaricus bernardii Salt-loving Agaricus In sandy soil often near beaches Choice D06 N Agaricus bisporus Button mushroom, was A. brunnescens Cultivated, and as escapee Edible D06 N F N Agaricus bitorquis Sidewalk mushroom In hard packed, disturbed soil Edible D06 N F N Agaricus brunnescens (old name) now A. bisporus D06 F N Agaricus campestris Meadow mushroom In meadows, pastures Choice D06 N V FV F V F FV N Agaricus comtulus Small slender agaricus In grassy places Not recommended D06 N V FV N Agaricus diminutivus group Diminutive agariicus, many similar species On humus in woods Similar to poisonous species D06 O V V Agaricus dulcidulus Diminutive agaric, in diminitivus group On humus in woods Similar to poisonous species D06 O V V Agaricus hondensis Felt-ringed agaricus In needle duff and among twigs Poisonous to many D06 N V V F N Agaricus integer In grassy places often with moss Edible D06 N V Agaricus meleagris (old name) now A moelleri or A. -

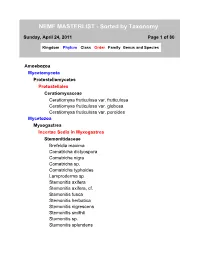

NEMF MASTERLIST - Sorted by Taxonomy

NEMF MASTERLIST - Sorted by Taxonomy Sunday, April 24, 2011 Page 1 of 80 Kingdom Phylum Class Order Family Genus and Species Amoebozoa Mycetomycota Protosteliomycetes Protosteliales Ceratiomyxaceae Ceratiomyxa fruticulosa var. fruticulosa Ceratiomyxa fruticulosa var. globosa Ceratiomyxa fruticulosa var. poroides Mycetozoa Myxogastrea Incertae Sedis in Myxogastrea Stemonitidaceae Brefeldia maxima Comatricha dictyospora Comatricha nigra Comatricha sp. Comatricha typhoides Lamproderma sp. Stemonitis axifera Stemonitis axifera, cf. Stemonitis fusca Stemonitis herbatica Stemonitis nigrescens Stemonitis smithii Stemonitis sp. Stemonitis splendens Fungus Ascomycota Ascomycetes Boliniales Boliniaceae Camarops petersii Capnodiales Capnodiaceae Capnodium tiliae Diaporthales Valsaceae Cryphonectria parasitica Valsaria peckii Elaphomycetales Elaphomycetaceae Elaphomyces granulatus Elaphomyces muricatus Elaphomyces sp. Erysiphales Erysiphaceae Erysiphe polygoni Microsphaera alni Microsphaera alphitoides Microsphaera penicillata Uncinula sp. Halosphaeriales Halosphaeriaceae Cerioporiopsis pannocintus Hysteriales Hysteriaceae Glonium stellatum Hysterium angustatum Micothyriales Microthyriaceae Microthyrium sp. Mycocaliciales Mycocaliciaceae Phaeocalicium polyporaeum Ostropales Graphidaceae Graphis scripta Stictidaceae Cryptodiscus sp. 1 Peltigerales Collemataceae Leptogium cyanescens Peltigeraceae Peltigera canina Peltigera evansiana Peltigera horizontalis Peltigera membranacea Peltigera praetextala Pertusariales Icmadophilaceae Dibaeis baeomyces Pezizales -

Ntfps in British Columbia

An Economic Strategy to Develop Non-Timber Forest Products and Services in British Columbia Forest Renewal BC Project No. PA97538-ORE Final Report Russel M. Wills and Richard G. Lipsey Cognetics International Research Inc. 579 Berry Road, Cates Hill Bowen Island, British Columbia V0N lG0 tel. 604-947027l fax: 604-9470270 email: [email protected] [email protected] March 15, 1999 acknowledgements We wish to express our deep appreciation to the companies which provided the information upon which this research is based and to our project colleagues from the Mount Currie Band, Lyle Leo, Loretta Steager and Sarah Brown. For information or for reviewing drafts of this work, we are also grateful to these people: Robert Adamson, Lynn Atwood, Paige Axelrood, Kelly Bannister, Shannon Berch, Keith Blatner, Tim Brigham, Sarah Brown, Todd Caldecott, Jim Cathcart, Jeff Chilton, Julien Davies, Fidel Fogarty, Steven Foster, Jim Frank, Shawn Freeman, Christopher French, Sharmin Gamiet, Swann Gardiner, Nelly De Geus, Steven Globerman, Andrea Gunnar, Richard Hallman, Evelyn Hamilton, Wendy Holm, James Hudson, Shun Ishiguru, Murray Isman, Eric Jones, Morley Lipsett, Yuan-chun Ma, Howard Mann, Allison McCutcheon, Richard Allen Miller, Stephen Mills, Darcy Mitchell, Gerrard Olivotto, Gabriel Perche, Scott Redhead, Hassan Salari, David Smith, Randy Spence, Neil Towers, Ian Townsend-Gault, Nancy Turner, Stephen Tyler, Gunta Vitens, James Weigand, and Charles Weiss. The mistakes which remain are ours. We express our gratitude also to Forest Renewal BC for funding this economic strategy and to our program officers at the Science Council of British Columbia, Louise Rees and John Matechuk, for their timely and efficient administration of this project. -

Ectomycorrhizal Species Registered in Douglas Fir Native Forests

VI Appendix 1: Ectomycorrhizal species registered in Douglas fir native forests. Species references comments Alpova diplophloeus (Zeller & Dodge) (8) Trappe & Smith Alpova trappei Fogel (6) (9) Amanita aprica Tulloss & Lindgren nom (10) not included prov. Amanita aspera (Fr.) Hooker (1) (9) Amanita chlorinosma (Peck) Lloyd (1) Amanita franchetii (Boud.) Fayod (10) Amanita gemmata (Fr.) Bertillon (1) (10) Amanita muscaria (L.) Hook. (1) (9) Amanita pachycolea D.E. Stuntz (10) Amanita pantherina Gonn. & Rabenh. (1) (9) (10) Amanita porphyria Fr. (9) Amanita silvicola Kauffman (1) (9) (10) Amanita smithiana Bas. (10) Amanita strobiliformis (Paulet ex Vittad.) (1) Bertill. Amanita vaginata (Bull.) Vittad. (1) (10) Amanita sp. (10) parasitized by sapedonium Balsamia magnata Harkn. (9) Balsamia nigrens Harkn. (2) Barssia oregonensis Gilkey (2) (4) (9) Boletellus zelleri (Murrill) Singer, Snell & (1) E.A. Dick Boletinus amabilis (Peck) Snell (1) Boletus chrysenteron gr. Bull. (9) (3) Boletus edulis Bull. (1) Boletus erythropus Krombh. (1) Boletus luridiformis Rostk. (10) Boletus mirabilis Murrill. (9) Boletus piperatus Bull. (9) Boletus subtomentosus Fr. (9) Boletus zelleri Murr. (9) Camarophyllus borealis (Peck) Murrill (9) Cantharellus cibarius Fr. (1) (7) Cantharellus floccosus Schw. (1) Cantharellus formosus Corner (9) (10) Cantharellus subalbidus A.H. Sm. & Morse (1) (9) (10) Cantharellus cf. sp. nov. Cenococcum graniforme (Sowerby) Ferd. & (1) Winge Chalciporus piperatoides (A.H. Sm. & (10) Thiers) T.J. Baroni & Both Chroogomphus tomentosus (Murrill) O.K. (9) Mill. Clavariadelphus ligula (Schaeff.) Donk (9) Clavariadelphus mucronatus V.L. Wells & (9) Kempton Clavulina sp (9) Cortinarius subg. Bulbopodium (9) 4 species Cortinarius subg. Cortinarius (9) 1 species C. limonius (Fr.) Fr. (10) VII C. -

<I>Rickenella Fibula</I>

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Masters Theses Graduate School 8-2017 Stable isotopes, phylogenetics, and experimental data indicate a unique nutritional mode for Rickenella fibula, a bryophyte- associate in the Hymenochaetales Hailee Brynn Korotkin University of Tennessee, Knoxville, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes Part of the Evolution Commons Recommended Citation Korotkin, Hailee Brynn, "Stable isotopes, phylogenetics, and experimental data indicate a unique nutritional mode for Rickenella fibula, a bryophyte-associate in the Hymenochaetales. " Master's Thesis, University of Tennessee, 2017. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/4886 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Hailee Brynn Korotkin entitled "Stable isotopes, phylogenetics, and experimental data indicate a unique nutritional mode for Rickenella fibula, a bryophyte-associate in the Hymenochaetales." I have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science, with a major in Ecology -

Molecular Phylogeny, Morphology, Pigment Chemistry and Ecology in Hygrophoraceae (Agaricales)

Fungal Diversity DOI 10.1007/s13225-013-0259-0 Molecular phylogeny, morphology, pigment chemistry and ecology in Hygrophoraceae (Agaricales) D. Jean Lodge & Mahajabeen Padamsee & P. Brandon Matheny & M. Catherine Aime & Sharon A. Cantrell & David Boertmann & Alexander Kovalenko & Alfredo Vizzini & Bryn T. M. Dentinger & Paul M. Kirk & A. Martyn Ainsworth & Jean-Marc Moncalvo & Rytas Vilgalys & Ellen Larsson & Robert Lücking & Gareth W. Griffith & Matthew E. Smith & Lorelei L. Norvell & Dennis E. Desjardin & Scott A. Redhead & Clark L. Ovrebo & Edgar B. Lickey & Enrico Ercole & Karen W. Hughes & Régis Courtecuisse & Anthony Young & Manfred Binder & Andrew M. Minnis & Daniel L. Lindner & Beatriz Ortiz-Santana & John Haight & Thomas Læssøe & Timothy J. Baroni & József Geml & Tsutomu Hattori Received: 17 April 2013 /Accepted: 17 July 2013 # The Author(s) 2013. This article is published with open access at Springerlink.com Abstract Molecular phylogenies using 1–4 gene regions and here in the Hygrophoraceae based on these and previous anal- information on ecology, morphology and pigment chemistry yses are: Acantholichen, Ampulloclitocybe, Arrhenia, were used in a partial revision of the agaric family Hygro- Cantharellula, Cantharocybe, Chromosera, Chrysomphalina, phoraceae. The phylogenetically supported genera we recognize Cora, Corella, Cuphophyllus, Cyphellostereum, Dictyonema, The Forest Products Laboratory in Madison, WI is maintained in cooperation with the University of Wisconsin and the laboratory in Puerto Rico is maintained in cooperation with the USDA Forest Service, International Institute of Tropical Forestry. This article was written and prepared by US government employees on official time and is therefore in the public domain and not subject to copyright. Electronic supplementary material The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s13225-013-0259-0) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users. -

Macrofungi of the Columbia River Basin

Report on Macrofungi of the Columbia River Basin By: Dr. Steven i. Miller Department of Botany University of Wyoming November 9,1994 Interior Columbia Basin Ecosystem Management Project Science Integration Team - Terrestrial Staff S. L. Miller--Eastside Ecosystem Management Project--l, Biogeography of taxonomic group Macrofungi found within the boundaries of the Eastside Ecosystem Management Project (EEMP) include three major subdivisions--Basidiomycotina, Ascomycotma and Zygomycotina. The subdivision Basidiomycotina. commonly known as the “Basidiomycetes”, include approximately 15,000 or more species. Fungi such as mushrooms, puffballs and polypores are some of the more commonly known and observed forms. Other forms which include the jelly fungi, birds nest fungi, and tooth fungi are also members of the Basidiomycetes. The majority of the Basidiomycetes are either saprouophs on decaying wood and other dead plant material, or are symbiotic with the living cells of plant roots, forming mycorrhizal associations with trees and shrubs. Others are parasites on living plants or fungi. Basidiomycotina are distributed worldwide. The Ascomycotina is the largest subdivision of true fungi, comprised of over 2000 genera. The “Ascomycetes”, as they are commonly referred to, include a wide range of diverse organisms such as yeasts, powdery mildews, cup fungi and truffles. The Ascomycetes are primarily terrestrial, although many live in fresh or marine waters. The majority of these fungi are saprotrophs on decaying plant debris. lMany sapronophic Ascomycetes specialize in decomposing certain host species or even are restricted to a particular part of the host such as leaves or petioles. Other specialized saprouophic types include those fungi that fotrn kuiting structures only where a fire recently occurred or on the dung of certain animals Xlany other Ascomycetes are parasites on plants and less commonly on insects or other animals. -

Mushrumors the Newsletter of the Northwest Mushroomers Association

MushRumors The Newsletter of the Northwest Mushroomers Association Volume 21 Issue 4, Part 1 October - December 2010 Mushroom Season for the Ages Yields Huge Dividend for the 2010 Northwest Mushroomers Association Fall Show With an unusually wet whether pattern establishing itself in the early part of June, long before the fall mushroom season would commence, there was a feeling of anticipation in the air, that a bountiful crop of mush- rooms just might be in the offing. We could not, however, have anticipated the extent of it. The duration of the fruiting, as well as the quantity of most photo by Jack Waytz of the desired edibles was astounding. Chanterelles were found in great num- bers until Thanksgiving, and normally hard to find, and highly prized cauli- flower mushrooms were wide spread over an almost unbelieveable period of the fall season. If one has the good for- tune to find one, they normally appear at the zenith of the fall season, in the early part of October. when the good rains have thoroughly permeated the thirsty substrates of the land. This year, I found the first of an incredible four, on the 19th of August, and the last, and best, in the middle of November, while on my last chanter- In this issue: Capturing the look of the temperate rainforest elle hunt of the Mushroom of the Month season. Inocybe praecox As usual, there were a few surprises in this season of such a wealth of By Dick Morrison Pg. 4 edibles. While there was a seemingly endless procession of Boletus mirabilis 2010 Fall Show Report available on virtually every submerged hemlock snag in Whatcom County, By Buck McAdoo Pg. -

Hygrophorus Annulatus, a New Edible Member of H. Olivaceoalbuscomplex from Southwestern China

Mycoscience VOL.62 (2021) 137-142 Short communication Hygrophorus annulatus, a new edible member of H. olivaceoalbus- complex from southwestern China Chao-Qun Wanga, Tai-Hui Lia,*, Xiang-Hua Wangb, Tie-Zheng Weic, Ming Zhanga, Xiao-Lan Hed a Guangdong Provincial Key Laboratory of Microbial Culture Collection and Application, State Key Laboratory of Applied Microbiology Southern China, Guang- dong Institute of Microbiology, Guangdong Academy of Sciences, Guangzhou 510070, Guangdong, China b CAS Key Laboratory for Plant Diversity and Biogeography of East Asia, Kunming Institute of Botany, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Kunming 650201, Yunnan, China c State Key Laboratory of Mycology, Institute of Microbiology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100101, China d Soil and Fertilizer Institute, Sichuan Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Chengdu 610066, Sichuan, China ABSTRACT Members of Hygrophorus olivaceoalbus-complex or olive waxcaps have both ecological and economic significance. European and North American species diversity of this fungal group has been presented in recent molecular phylogenetic studies, but no Chinese materials were included. In this study, a phylogenetic overview of the H. olivaceoalbus-complex based on internal transcribed spacer (ITS) sequenc- es was made, and a local popular edible species from southwestern China was described as a new species H. annulatus. This new species is characterized by grayish brown, olive brown to dark brown pileus disc, inflexed to deflexed pileus margin, obvious and dark brown annulus, basidiospores measuring (8.0–)8.5–11.0(–12.0) × 5.0–7.5(–8.0) μm, and the distribution in subalpine forests dominated by Abies and/or Picea in southwestern China. Keywords: Basidiomycota, Hygrophoraceae, olive waxcaps, phylogeny, taxonomy Article history: Received 30 July 2020, Revised 13 January 2021, Accepted 14 January 2021, Available online 20 March 2021.