University Admissions by Individual Schools

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fortismere Forges New Links with N2

Local News is our Aim THE CAR SERVICE Professional Sales & Lettings AT COMPETITIVE RATES 020 8883 5000 020 8444 5222 [email protected] November 2007 No. 170 20p ARCHER ISSN 1361-3952 wheresold A community newspaper for East Finchley run entirely by volunteers. Fortismere forges new links with N2 By John Lawrence Fortismere School is seeking to build new links with East Finchley and encourage more applications from families in N2 as well as Muswell Hill. September was an impor- “Being on the boundary of be run in the same way as if tant date for the school as it Haringey and Barnet means it had continued to be a com- moved into Foundation School that the school will always wel- munity school. status and, after many years of come applications for places Other plans put forward by being a specialist technology from families in both Muswell the governors are to extend college, changed its specialist Hill and East Finchley.” Fortismere’s services to all status to Maths/Computing The move to foundation local families by offering and Music. status was opposed by some evening or weekend courses, In addition, following an parents and staff, who formed such as Mandarin, Spanish, excellent Ofsted report in the Keep Fortismere Compre- maths for parents, computing which the school was described hensive campaign group. The for beginners, website design, as having ‘many outstanding group says it will carry on orchestra and instrumental features’, Fortismere has been campaigning for the school to lessons. formally identiied as a High Performing Specialist School and, as such, has been offered PRICKETT 36 High Road the opportunity to take on & ELLIS East Finchley N2 9PJ a second specialism, which will be Modern Foreign Lan- TOMKINS guages. -

TYPE Aylesbury Grammar School Further Offers Ma

Moving up to Secondary School in September 2014 Second Round Allocation Positions GRAMMAR SCHOOLS GRAMMAR SCHOOLS - ALLOCATION PROFILE (qualified applicants only) TYPE Further offers made under rule 4 (linked siblings), and some under rule 7 (catchment) to a distance of 1.291 Aylesbury Grammar School Academy miles. Aylesbury High School All applicants offered. Academy Beaconsfield High School All applicants offered. Foundation Burnham Grammar School Further offers made under rule 5 (distance) to 10.456 miles. Academy Chesham Grammar School All applicants offered. Academy Dr Challoner's Grammar School Further offers made under rule 4 (catchment) to a distance of 7.378 miles. Academy Dr Challoner's High School Further offers made under rule 2 (catchment) to a distance of 6.330 miles. Academy John Hampden Grammar School All applicants offered. Academy The Royal Grammar School Further offers made under rule 2 (catchment) and some under rule 6 (distance) to 8.276 miles. Academy The Royal Latin School Further offers made under rule 2 (catchment) some under rule 5 (distance) to 7.661 miles. Academy Sir Henry Floyd Grammar School All applicants offered. Academy Further offers made under rule 2{3}(catchment siblings) and some under rule 2 (catchment), to a distance of Sir William Borlase's Grammar School Academy 0.622 miles. Wycombe High School Further offers made under rule b (catchment) and some under rule d (distance) to 16.957 miles. Academy UPPER SCHOOLS UPPER SCHOOLS - ALLOCATION PROFILE TYPE Further offers made under rule b (catchment), rule c (siblings) and some under rule e (distance) to 4.038 Amersham School Academy miles. -

Report on the Second York Schools Science Quiz on Thursday 12 March, Thirteen Schools from in and Around York Came Together

Report on the Second York Schools Science Quiz On Thursday 12 March, thirteen schools from in and around York came together for the second York Schools Science Quiz. Twenty two school teams competed along with four teacher teams (put together from the teachers who brought the pupils along from the various schools) for the trophies and prizes. Each team consisted of two Lower Sixth and two Fifth Form pupils or four Fifth Form pupils for those schools without Sixth Forms. The schools represented were Manor CE School, Canon Lee School, The Joseph Rowntree School, Huntington School, Archbishop Holgate’s School, Fulford School, All Saints School, Millthorpe School, St Peter’s School, Bootham School, The Mount School, Selby High School and Scarborough College. The event took place as part of the York ISSP and also the York Schools Ogden Partnership, with a large thank you to the Royal Society of Chemistry and the Institute of Physics for some of the prizes, the Rotary Club of York Vikings for the water bottles and the Ogden Trust for the 8 GB memory sticks and Amazon Voucher prizes. The quiz was put together and presented by Sarah McKie, who is the Head of Biology at St Peter’s School, and consisted of Biology, Chemistry and Physics rounds alongside an Observation Challenge and a Hitting the Headlines round amongst others. At the end of the quiz the teams waited with bated breath for the results to be announced. It turned out that three teams were tied for second place, so a tie breaker was needed to separate them. -

West Midlands Schools

List of West Midlands Schools This document outlines the academic and social criteria you need to meet depending on your current secondary school in order to be eligible to apply. For APP City/Employer Insights: If your school has ‘FSM’ in the Social Criteria column, then you must have been eligible for Free School Meals at any point during your secondary schooling. If your school has ‘FSM or FG’ in the Social Criteria column, then you must have been eligible for Free School Meals at any point during your secondary schooling or be among the first generation in your family to attend university. For APP Reach: Applicants need to have achieved at least 5 9-5 (A*-C) GCSES and be eligible for free school meals OR first generation to university (regardless of school attended) Exceptions for the academic and social criteria can be made on a case-by-case basis for children in care or those with extenuating circumstances. Please refer to socialmobility.org.uk/criteria-programmes for more details. If your school is not on the list below, or you believe it has been wrongly categorised, or you have any other questions please contact the Social Mobility Foundation via telephone on 0207 183 1189 between 9am – 5:30pm Monday to Friday. School or College Name Local Authority Academic Criteria Social Criteria Abbot Beyne School Staffordshire 5 7s or As at GCSE FSM or FG Alcester Academy Warwickshire 5 7s or As at GCSE FSM Alcester Grammar School Warwickshire 5 7s or As at GCSE FSM Aldersley High School Wolverhampton 5 7s or As at GCSE FSM or FG Aldridge -

Community Appendices

COMMUNITY AND LEISURE APPENDICES C1 – C5 Appendix C1 Community buildings in Beaconsfield Appendix C2 Current sports provision in Beaconsfield Appendix C3 A multi-sports facility for Beaconsfield Appendix C4 Multi-use sports concept Appendix C5 Arts/community centre and theatre APPENDIX C1 – COMMUNITY BUILDINGS IN BEACONSFIELD Size Capacity Name of building Metres (if relevant) Publicly Owned buildings Beacon Centre (Owned by SBDC – let to Sports Hall, Gym, Theatre 209 Better) (plus stage) Town Hall – Beaconsfield Chambers 70 (plus kitchen) (owned by SBDC – let to Town Council) Curzon Centre (owned by Bucks CC – let Page Hall 21 x 12 250 to Curzon Centre Management Page Hall – stage 13.5 x 12 committee) Owen Room 11 x 8.5 100 (plus foyer and kitchen) Watson Room 8.5 x 6 80 Town Library (BCC) Coroner’s Court (BCC) Privately Owned Buildings Fitzwilliams Centre (owned by Main Hall & kitchen 15 x 7 120 Beaconsfield Anglican Team Ministry) Room 1 8 x 6 40 Room 2 6 x 4.6 30 (plus foyer and kitchen) Room 3 4.5 x 4 12 Masonic Hall (long lease to Nearly always fully booked Beaconsfield Masons) St Michael’s Hall & Community Hall & kitchen 100 Resources centre (Anglicans) CCRC dividable room 20 + 20 St Thomas’ Church Hall Hall and kitchen 80 St Teresa’s Parish Centre (RC) Can be 1 large hall for 150 or smaller hall of 80 80 and 2 small rooms for 25 URC Hall (Aylesbury End) 80 URC Hall (Crabtree Close) 40 The Reading Room 30 Schools All the local schools offer their buildings for community use. -

West Sept-Dec 2015 Parent and Carer Support Booklet

Programmes, Activities and Groups for parents and carers in West Edinburgh Sept-Dec 2015 1 Contents Page New services – Childcare for eligible two year olds. Fox Covert Early Years Centre. 4 Parenting Programmes Mellow Bumps 5 Peep 6-7 The Psychology of Parenting Project (PoPP) : The Incredible Years / Triple P 8-9 Raising Children with Confidence 10 Raising Teens with Confidence 11 Teen Triple P 12 Parent and Child Activities Adult and child swim sessions 13 Baby Massage 13 Bookbug 13-14 Buggy Walks 14 Cooking with kids 15 Craft Fridays 15 Diggers and Dreamers 15 Early Years Group 15 Family Forest Schools 15 Family Learning 16 Family Swim Sessions 16 Funky Fridays 16 Get Going (weight management) 17 Homework Club 17 Parent and Child Workshops 17 Play, Stay and Read 17 Play@Home 18 Storytime 18 The Drop-In 18 Us Together Activity Group 18 2 Parent Groups The Cool Club 19 Dads’ Club 19 Foster Carers’ Group 19 JUNO 19 People First Parents’ Group 19 English for Speakers of Other Languages 21 (ESOL) Support and Advice (NHS and City Edinburgh Coucil) Ante Natal Classes / Parent craft classes 22 New Parents’ Group 22 New Baby Groups 22-23 Breastfeeding and Weaning Advice 23 Parent Information Points and drop-in 24 Support and Advice - Organisations Crossreach – postnatal depression 25 Children 1st - family support 25 Dads Rock – counselling 25 Families Need Fathers 25 First Hand 26 Home Start – family support 26 Making it Work for lone parents (employment 27 One Parent Families Scotland 27 The Edinburgh Lone Fathers Project 27 Playgroups 28 Activities for all ages 29 Early Years Centres and Hubs 30 Contacts 32 3 New Service Early learning and childcare for eligible two year olds Certain children are entitled to receive up to 600 hours of free early learning and childcare during school terms. -

Buckinghamshire Standing Advisory Council on Religious Education

Buckinghamshire Standing Advisory Council on Religious Education Annual Report 2017-18 Learning and growing through challenging RE 1 Contents Page No. Foreword from the Chair……………………………………………………………….. 1. Standards and quality of provision of RE: 2. Managing the SACRE and Partnership with the LA and Other Key Stakeholders: 3. Effectiveness of the Agreed Syllabus: 4. Collective Worship: 5. SACRE and School Improvement: Appendix 1: Examination data…………………….………………………………… Appendix 2: Diversity in Christianity ……………………………………………… Appendix 3: SACRE Membership and attendance for the year 2016/2017…… 2 Learning and growing through challenging RE Foreword from the Chair of SACRE September 2017 - July 2018 As with any organisation it is the inspiration given by the members that provides the character. I shall focus on some of the creativity we have valued in Bucks SACRE this year both from our members and during our visits to schools. In addition, we receive wise counsel from our Education Officer at Bucks CC, Katherine Wells and our RE Adviser Bill Moore. At our meeting in October we learned that Suma Din our Muslim deputy had become a school governor and would no longer fulfil her role with SACRE. However, her legacy to us is her book published by the Institute of Education Press entitled ‘Muslim Mothers and their children’s schooling.’ See SACRED 7, for a review. (For this and all other references to SACRED see the website at the end of this section). In her contribution to SACRED 6 Suma wrote; From the Qur’an, I understand my role as being a ‘steward’ on this earth; one who will take care, take responsibility and hand on a legacy to those who come after them. -

Listado De Internados En Inglaterra

INGLATERRA COLEGIOS INTERNADOS PRECIOS POR TERM (4 MESES) MÁS DE 350 COLEGIOS Tarifas oficiales de los colegios internados añadiendo servicio de tutela en Inglaterra registrado en AEGIS a partir de £550 por term cumpliendo así con la legislación inglesa actual y con el estricto código de buenas prácticas de estudiantes internacionales Precio 1 Term Ranking Precio 1 Term Ranking Abbey DLD College London £8,350 * Boundary Oak School £7,090 * Abbots Bromley School £9,435 290 Bournemouth Collegiate £9,100 382 Abbotsholme School £10,395 * Box Hill School £10,800 414 Abingdon School £12,875 50 Bradfield College £11,760 194 Ackworth School £8,335 395 Brandeston Hall £7,154 * ACS Cobham £12,840 * Bredon School £9,630 * Adcote School £9,032 356 Brentwood School £11,378 195 Aldenham School £10,482 * Brighton College £13,350 6 Aldro School £7,695 * Bromsgrove School £11,285 121 Alexanders College £9,250 0 Brooke House College £9,900 * Ampleforth College £11,130 240 Bruton School for Girls £9,695 305 Ardingly College £10,710 145 Bryanston School £11,882 283 Ashbourne College £8,250 0 Burgess Hill School for Girls £10,150 112 Ashford School £11,250 254 Canford School £11,171 101 Ashville College £9,250 355 Casterton Sedbergh Prep £7,483 * Badminton School £11,750 71 Caterham School £10,954 65 Barnard Castle School £8,885 376 Catteral Hall £7,400 * Barnardiston Hall Prep £6,525 * Cheltenham College £11,865 185 Battle Abbey School £9,987 348 Chigwell School £9,310 91 Bede's £11,087 296 Christ College Brecon £8,994 250 Bede's Prep School £8,035 * Christ's -

Annual Review 2018 – 19

ANNUAL REVIEW 2018 – 19 “Sport has the power to change the world. It has the power to inspire. It has the power to unite people in a way that little else does. It speaks to youth in a language they understand. Sport can create hope where once there was only despair” - Nelson Mandela - 2 Foreword… 2018-19 was a year of self-reflection for the Active Schools team, having completed the Insights Personality test. Understanding others and appreciating our differences was one of the key learnings. This programme helped us build valuable working relationships and a network of partners, allowing Active Schools to make the impact they have made this year. The Active Schools team continue to work with and nurture senior pupils who officiate, coach, organise competitions, become Young Ambassadors who are our decision makers. Gaining relevant sports qualifications and valuable experience in delivery, the young people are able to Jude Salmon develop their employability skills. Active Schools Manager In today’s world we are affected by factors including stress, mental health, obesity and poverty. Taking part in sport and physical activity truly does make a difference to our lives and I hope that some of the stories you are about to read will illustrate this to you. The phrase, ‘healthy body, healthy mind’ says it all. Our bodies were designed to move and when we keep them healthy, we have a better outlook on life, and on learning. The most wonderful part of keeping fit and healthy is that it is fun, but as this annual review shows, it can also open doors into future careers through volunteering and coaching. -

London Borough of Haringey Pension Fund Pension Fund Annual Report 2019/20 Contents

London Borough of Haringey Pension Fund Pension Fund Annual Report 2019/20 Contents ........................................................................................................................................... 3 ........................................................................... 5 ............................................................................................................. 6 ................................................................................................................................ 8 .................................................................................................................... 9 ................................................................................................ 11 .................................................................................................................................... 13 .................................................................................. 17 ....................................................................................................................... 18 ................................................................................................................ 20 ............................................................................................................................... 21 ............................................................................................................... 24 ....................................................................................................................... -

The Stourbridge School of Art and Its Relations with the Glass Industry of the Stourbridge District, 1850-1905

A PROVINCIAL SCHOOL OF ART AND LOCAL INDUSTRY: THE STOURBRIDGE SCHOOL OF ART AND ITS RELATIONS WITH THE GLASS INDUSTRY OF THE STOURBRIDGE DISTRICT, 1850-1905 by JAMES SCOTT MEASELL A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of History College of Arts and Law University of Birmingham April 2016 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT Founded in 1851, the Stourbridge School of Art offered instruction in drawing, art and design to students engaged in industries, especially glass. Using social history methodology and primary sources such as Government reports, local newspapers and school records, this thesis explores the school’s development from 1850 to 1905 and explicates its relationships with the local glass industry. Within the context of political, economic, social and cultural forces, the school contributed to the town’s civic culture and was supported by gentry, clergy and industrialists. The governing Council held public meetings and art exhibitions and dealt with management issues. Working class men attended evening classes. Women from wealthy families attended morning classes. -

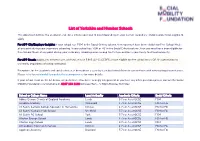

List of Yorkshire and Humber Schools

List of Yorkshire and Humber Schools This document outlines the academic and social criteria you need to meet depending on your current secondary school in order to be eligible to apply. For APP City/Employer Insights: If your school has ‘FSM’ in the Social Criteria column, then you must have been eligible for Free School Meals at any point during your secondary schooling. If your school has ‘FSM or FG’ in the Social Criteria column, then you must have been eligible for Free School Meals at any point during your secondary schooling or be among the first generation in your family to attend university. For APP Reach: Applicants need to have achieved at least 5 9-5 (A*-C) GCSES and be eligible for free school meals OR first generation to university (regardless of school attended) Exceptions for the academic and social criteria can be made on a case-by-case basis for children in care or those with extenuating circumstances. Please refer to socialmobility.org.uk/criteria-programmes for more details. If your school is not on the list below, or you believe it has been wrongly categorised, or you have any other questions please contact the Social Mobility Foundation via telephone on 0207 183 1189 between 9am – 5:30pm Monday to Friday. School or College Name Local Authority Academic Criteria Social Criteria Abbey Grange Church of England Academy Leeds 5 7s or As at GCSE FSM Airedale Academy Wakefield 4 7s or As at GCSE FSM or FG All Saints Catholic College Specialist in Humanities Kirklees 4 7s or As at GCSE FSM or FG All Saints' Catholic High