Tin Pan Alley OTHER BOOKS by the AUTHOR

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alshire Records Discography

Alshire Discography by David Edwards, Mike Callahan & Patrice Eyries © 2018 by Mike Callahan Alshire International Records Discography Alshire was located at P.O. Box 7107, Burbank, CA 91505 (Street address: 2818 West Pico Boulevard, Los Angeles, CA 90006). Founded by Al Sherman in 1964, who bought the Somerset catalog from Dick L. Miller. Arlen, Grit and Oscar were subsidiaries. Alshire was a grocery store rack budget label whose main staple was the “101 Strings Orchestra,” which was several different orchestras over the years, more of a franchise than a single organization. Alshire M/S 3000 Series: M/S 3001 –“Oh Yeah!” A Polka Party – Coal Diggers with Happy Tony [1967] Reissue of Somerset SF 30100. Oh Yeah!/Don't Throw Beer Bottles At The Band/Yak To Na Wojence (Fortunes Of War)/Piwo Polka (Beer Polka)/Wanda And Stash/Moja Marish (My Mary)/Zosia (Sophie)/Ragman Polka/From Ungvara/Disc Jocky Polka/Nie Puki Jashiu (Don't Knock Johnny) Alshire M/ST 5000 Series M/ST 5000 - Stephen Foster - 101 Strings [1964] Beautiful Dreamer/Camptown Races/Jeannie With The Light Brown Hair/Oh Susanna/Old Folks At Home/Steamboat 'Round The Bend/My Old Kentucky Home/Ring Ring De Bango/Come, Where My Love Lies Dreaming/Tribute To Foster Medley/Old Black Joe M/ST 5001 - Victor Herbert - 101 Strings [1964] Ah! Sweet Mystery Of Life/Kiss Me Again/March Of The Toys, Toyland/Indian Summer/Gypsy Love Song/Red Mill Overture/Because You're You/Moonbeams/Every Day Is Ladies' Day To Me/In Old New York/Isle Of Our Dreams M/S 5002 - John Philip Sousa, George M. -

Ralph W. Judd Collection on Cross-Dressing in the Performing Arts

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt487035r5 No online items Finding Aid to the Ralph W. Judd Collection on Cross-Dressing in the Performing Arts Michael P. Palmer Processing partially funded by generous grants from Jim Deeton and David Hensley. ONE National Gay and Lesbian Archives 909 West Adams Boulevard Los Angeles, California 90007 Phone: (213) 741-0094 Fax: (213) 741-0220 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.onearchives.org © 2009 ONE National Gay and Lesbian Archives. All rights reserved. Finding Aid to the Ralph W. Judd Coll2007-020 1 Collection on Cross-Dressing in the Performing Arts Finding Aid to the Ralph W. Judd Collection on Cross-Dressing in the Performing Arts Collection number: Coll2007-020 ONE National Gay and Lesbian Archives Los Angeles, California Processed by: Michael P. Palmer, Jim Deeton, and David Hensley Date Completed: September 30, 2009 Encoded by: Michael P. Palmer Processing partially funded by generous grants from Jim Deeton and David Hensley. © 2009 ONE National Gay and Lesbian Archives. All rights reserved. Descriptive Summary Title: Ralph W. Judd collection on Cross-Dressing in the Performing Arts Dates: 1848-circa 2000 Collection number: Coll2007-020 Creator: Judd, Ralph W., 1930-2007 Collection Size: 11 archive cartons + 2 archive half-cartons + 1 records box + 8 oversize boxes + 19 clamshell albums + 14 albums.(20 linear feet). Repository: ONE National Gay and Lesbian Archives. Los Angeles, California 90007 Abstract: Materials collected by Ralph Judd relating to the history of cross-dressing in the performing arts. The collection is focused on popular music and vaudeville from the 1890s through the 1930s, and on film and television: it contains few materials on musical theater, non-musical theater, ballet, opera, or contemporary popular music. -

A Reading from the Psalms a Prayer of Mannasseh Monday

o Lord, open our lips MONDAY and our mouth shall proclaim your praise. o God, you are our God; eagerly we seek you; A PRAYER OF MANNASSEH our souls thirst for you. Our flesh also faints for you, Lord almighty and God of our forebears. as in a dry and thirsty land where there is no water. you who made heaven and earth in all their glory: All things tremble with awe at your presence, So would we gaze upon you in your holy place, before your great and mighty power. that we might behold your power and your glory. Immeasurable and unsearchable is your promised mercy, Your loving-kindness is better than life itself for you are God, Most High. and so our lips shall praise you. You are full of compassion, We will bless you as long as we live long-suffering and very merciful, and lift up our hands in your name. and you relent at human suffering. from Pm/m 63 O God, according to your great goodness, you have promised forgiveness for repentance to those who have sinned against you. The sins I have committed against you are more in number than the sands of the sea. I am not worthy to look up to the height of heaven, Blessed are you. God of compassion and mercy, because of the multitude of my iniquities. to you be praise and glory for ever. In the darkness of our sin, And now I bend the knee of my heart before you, your light breaks forth like the dawn imploring your kindness upon me. -

Finding Aid for the Sheldon Harris Collection (MUM00682)

University of Mississippi eGrove Archives & Special Collections: Finding Aids Library November 2020 Finding Aid for the Sheldon Harris Collection (MUM00682) Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/finding_aids Recommended Citation Sheldon Harris Collection, Archives and Special Collections, J.D. Williams Library, The University of Mississippi This Finding Aid is brought to you for free and open access by the Library at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Archives & Special Collections: Finding Aids by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. University of Mississippi Libraries Finding aid for the Sheldon Harris Collection MUM00682 TABLE OF CONTENTS SUMMARY INFORMATION Summary Information Repository University of Mississippi Libraries Biographical Note Creator Scope and Content Note Harris, Sheldon Arrangement Title Administrative Information Sheldon Harris Collection Related Materials Date [inclusive] Controlled Access Headings circa 1834-1998 Collection Inventory Extent Series I. 78s 49.21 Linear feet Series II. Sheet Music General Physical Description note Series III. Photographs 71 boxes (49.21 linear feet) Series IV. Research Files Location: Blues Mixed materials [Boxes] 1-71 Abstract: Collection of recordings, sheet music, photographs and research materials gathered through Sheldon Harris' person collecting and research. Prefered Citation Sheldon Harris Collection, Archives and Special Collections, J.D. Williams Library, The University of Mississippi Return to Table of Contents » BIOGRAPHICAL NOTE Born in Cleveland, Ohio, Sheldon Harris was raised and educated in New York City. His interest in jazz and blues began as a record collector in the 1930s. As an after-hours interest, he attended extended jazz and blues history and appreciation classes during the late 1940s at New York University and the New School for Social Research, New York, under the direction of the late Dr. -

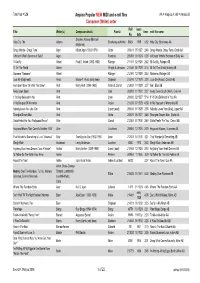

Ampico Popular NEW MIDI and E-Roll Files Composer

Total files = 536 Ampico Popular NEW MIDI and e-roll files AA = Ampico A, AB = Ampico B Composer (Writer) order Roll issue Title Writer(s) Composer details Pianist time midi file name No. date Stephen Adams (Michael Holy City, The Adams Brockway as Kmita 56824 1919 4:52 Holy City, Brockway AA Maybrick) Crazy Words - Crazy Tune Ager Milton Ager (1893-1979) Grofe 208611 05 1927 2:48 Crazy Words, Crazy Tune, Grofe AA I Wonder What's Become of Sally? Ager Fairchild 205191 09 1924 4:28 I Wonder What's Become of Sally AA I'll Get By Ahlert Fred E. Ahlert (1892-1953) Rainger 211171 02 1929 2:42 I'll Get By, Rainger AB I'll Tell The World Ahlert Wright & Johnston 211541 05 1929 3:14 I'll Tell The World (Ahlert) AB Marianne "Marianne" Ahlert Rainger 212191 12 1929 2:44 Marianne, Rainger AB Love Me (Deja) waltz Aivaz Morse-T. Aivaz (only item) Shipman 212241 12 1929 3:20 Love Me (Aivaz), Carroll AB Am I Blue? from "On With The Show" Akst Harry Akst (1894-1963) Arden & Carroll 212031 10 1929 3:37 Am I Blue AB Away Down South Akst Clair 203051 11 1922 2:37 Away Down South (Akst), Clair AA If I'd Only Believed In You Akst Lane 208383 02 1927 5:14 If I'd Only Believed In You AA In My Bouquet Of Memories Akst Arden 210233 07 1928 4:58 In My Bouquet of Memories AB Nobody Loves You Like I Do Akst Lopez (asst) 205531 01 1925 2:38 Nobody Loves You (Akst), Lopez AA Shanghai Dream Man Akst Grofe 208621 05 1927 3:48 Shanghai Dream Man, Grofe AA Gotta Feelin' For You "Hollywood Revue" Alter Carroll 212351 01 1930 2:49 Gotta Feelin' For You, Carroll AB Hugs and -

Brian Casserly, Who Also Goes by the Name "Big B" Plays Trumpet, Trombone and Is Also a Vocalist with the Band

Cornet Chop Suey – Biographies The Cornet Chop Suey Jazz Band has enjoyed a meteoric rise in popularity since its arrival on the jazz scene in 2001. The band's unique front line with Brian Casserly on trumpet, Tom Tucker on cornet, Jerry Epperson on reeds and Brett Stamps on trombone is driven by a powerful rhythm section consisting of Paul Reid on piano, Al Sherman on bass and John Gillick on drums. Best known for a wide variety of styles, Cornet Chop Suey applies its own exciting style to traditional jazz, swing, blues and "big production" numbers. Every performance by Cornet Chop Suey is a high-energy presentation and is always a memorable experience for the audience. Named after a somewhat obscure Louis Armstrong composition, Cornet Chop Suey now has six CD's available. The "St. Louis Armstrong" CD includes many of the tunes performed in the special Louis Armstrong show. The band is in great demand at jazz festivals, jazz cruises, conventions and concerts around the country. Brian Casserly, who also goes by the name "Big B" plays trumpet, trombone and is also a vocalist with the band. A professional musician since the age of 14, Brian has played for many greats in the music business, including Tony Bennett,Tex Beneke, Stan Kenton, Chuck Berry and even Tiny Tim. He has also played the prestigious Monterey Pops Festival for several years. An in-demand session musician, Brian has performed in many commercials, recordings and musicals in the U.S. and Canada and is the past musical director for the S.S. -

Chronology and Itinerary of the Career of J. Tim Brymn Materials for a Biography Peter M

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Faculty Publications: School of Music Music, School of 8-26-2016 Chronology and Itinerary of the Career of J. Tim Brymn Materials for a Biography Peter M. Lefferts University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/musicfacpub Part of the African American Studies Commons, American Popular Culture Commons, and the Music Commons Lefferts, Peter M., "Chronology and Itinerary of the Career of J. Tim Brymn Materials for a Biography" (2016). Faculty Publications: School of Music. 64. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/musicfacpub/64 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Music, School of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications: School of Music by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. 1 08/26/2016 Chronology and Itinerary of the Career of J. Tim Brymn Materials for a Biography Peter M. Lefferts University of Nebraska-Lincoln This document is one in a series---"Chronology and Itinerary of the Career of"---devoted to a small number of African American musicians active ca. 1900-1950. They are fallout from my work on a pair of essays, "US Army Black Regimental Bands and The Appointments of Their First Black Bandmasters" (2013) and "Black US Army Bands and Their Bandmasters in World War I" (2012/2016). In all cases I have put into some kind of order a number of biographical research notes, principally drawing upon newspaper and genealogy databases. None of them is any kind of finished, polished document; all represent work in progress, complete with missing data and the occasional typographical error. -

Ac-Cent-Tchu-Ate the Positive Achin Hearted Blues After Youve Gone

Ac-cent-tchu-ate The Positive Baltimore Bluesette Achin Hearted Blues Barbados Bluesology After Youve Gone Basin Street Blues Bluin The Blues Afternoon In Paris Battle Hymn Of The Republic Body And Soul Again Baubles Bangles And Beads Bohemia After Dark Aggravatin Papa Be My Love Bouncing With Bud Ah-leu-cha Beale Street Blues Bourbon Street Parade Aint Cha Glad Beale Street Mama Breeze And J Aint Misbehavin Beau Koo Jack Breezin Along With The Breeze Aint She Sweet Beautiful Love Broadway Air Mail Special BeBop Brother Can You Spare A Dime Airegin Because Of You Brown Sugar Alabama Jubilee Begin The Beguine Buddy Boldens Blues Alabamy Bound Bei Mir Bist Du Schoen Buddys Habits Alexanders Ragtime Band Believe It Beloved Budo Alice Blue Gown Bemsha Swing Bugle Boy March All Alone Bernies Tune Bugle Call Rag All Gods Chillun Got Rhythm Besame Mucho But Beautiful All I Do Is Dream Of You Besie Couldnt Help It But Not For Me All My Life Best Things In Life Are Free Button Up Your Overcoat All Of Me Between The Devil And The Deep Buzzy All Of You Blue Sea By The Beautiful Sea All Or Nothing At All Bewitched By The Light Of The Silvery Moon All That Meat And No Potatoes Beyond The Blue Horizon By The River Sainte Marie All The Things You Are Biden’ My Time By The Waters Of Minnetonka All Through The Night Big Butter And Egg Man Bye And Bye All Too Soon Big Noise From Winnetka Bye Bye Blackbird Alligator Crawl Bill Bailey Bye Bye Blues Almost Like Being In Love Billie Boy C Jam Blues Alone Billies Bounce Cakewalking Babies From Home Alone Together -

The Sam Eskin Collection, 1939-1969, AFC 1999/004

The Sam Eskin Collection, 1939 – 1969 AFC 1999/004 Prepared by Sondra Smolek, Patricia K. Baughman, T. Chris Aplin, Judy Ng, and Mari Isaacs August 2004 Library of Congress American Folklife Center Washington, D. C. Table of Contents Collection Summary Collection Concordance by Format Administrative Information Provenance Processing History Location of Materials Access Restrictions Related Collections Preferred Citation The Collector Key Subjects Subjects Corporate Subjects Music Genres Media Formats Recording Locations Field Recording Performers Correspondents Collectors Scope and Content Note Collection Inventory and Description SERIES I: MANUSCRIPT MATERIAL SERIES II: SOUND RECORDINGS SERIES III: GRAPHIC IMAGES SERIES IV: ELECTRONIC MEDIA Appendices Appendix A: Complete listing of recording locations Appendix B: Complete listing of performers Appendix C: Concordance listing original field recordings, corresponding AFS reference copies, and identification numbers Appendix D: Complete listing of commercial recordings transferred to the Motion Picture, Broadcast, and Recorded Sound Division, Library of Congress 1 Collection Summary Call Number: AFC 1999/004 Creator: Eskin, Sam, 1898-1974 Title: The Sam Eskin Collection, 1938-1969 Contents: 469 containers; 56.5 linear feet; 16,568 items (15,795 manuscripts, 715 sound recordings, and 57 graphic materials) Repository: Archive of Folk Culture, American Folklife Center, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. Summary: This collection consists of materials gathered and arranged by Sam Eskin, an ethnomusicologist who recorded and transcribed folk music he encountered on his travels across the United States and abroad. From 1938 to 1952, the majority of Eskin’s manuscripts and field recordings document his growing interest in the American folk music revival. From 1953 to 1969, the scope of his audio collection expands to include musical and cultural traditions from Latin America, the British Isles, the Middle East, the Caribbean, and East Asia. -

Vaudeville Trails Thru the West"

Thm^\Afest CHOGomTfca3M^si^'reirifii ai*r Maiiw«MawtiB»ci>»«w iwMX»ww» cr i:i wmmms misssm mm mm »ck»: m^ (sam m ^i^^^ This Book is the Property of PEi^MYOcm^M.AGE :m:^y:^r^''''< .y^''^..^-*Ky '''<. ^i^^m^^^ BONES, "Mr. Interlocutor, can you tell me why Herbert Lloyd's Guide Book is like a tooth brush?" INTERL. "No, Mr, Bones, why is Herbert Lloyd's Guide Book like a tooth brush?" BONES, "Because everybody should have one of their own". Give this entire book the "Once Over" and acquaint yourself with the great variety of information it contains. Verify all Train Times. Patronize the Advertisers, who I PLEASE have made this book possible. Be "Matey" and boost the book. This Guide is fully copyrighted and its rights will be protected. Two other Guide Books now being compiled, cover- ing the balance of the country. Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2012 with funding from Brigham Young University http://archive.org/details/vaudevilletrailsOOIIoy LIBRARY Brigham Young University AMERICANA PN 3 1197 23465 7887 — f Vauaeville Trails Thru tne ^iV^est *' By One vC^Jio Knows' M Copyrighted, 1919 by HERBERT LLOYD msiGimM wouNG<uNiveRSBtr UPb 1 HERBERT LLOYD'S VAUDEVILLE GUIDE GENERAL INDEX. Page Page Addresses 39 Muskogee 130-131 Advertiser's Index (follows this index) New Orleans 131 to 134 Advertising Rates... (On application) North Yakima 220 Calendar for 1919.... 30 Oakland ...135 to 137 Calendar for 1920 31 Ogden 138-139 Oklahoma City 140 to 142 CIRCUITS. Omaha 143 to 145 Ackerman Harris 19 & Portland 146 to 150 Interstate . -

Title Composer Lyricist Arranger Cover Artist Publisher Date Notes Wabash Blues Fred Meinken Dave Ringle Leo Feist Inc

Title Composer Lyricist Arranger Cover artist Publisher Date Notes Wabash Blues Fred Meinken Dave Ringle Leo Feist Inc. 1921 Wabash Cannon Ball Wm Kindt Wm Kindt NPS Calumet Music Co. 1939 High Bass arranged by Bill Burns Wabash Moon Dave Dreyer Dave Dreyer Irving Berlin Inc. 1931 Wagon Wheels Peter DeRose Billy Hill Shapiro, Bernstein & Co. 1934 Wagon Wheels Peter DeRose Billy Hill Geoffrey O'Hara Shapiro, Bernstein & Co., Inc. 1942 Arranged for male voices (T.T.B.B.) Wah-Hoo! Cliff Friend Cliff Friend hbk Crawford Music Corp. 1936 Wait for Me Mary Charlie Tobias Charlie Tobias Harris Remick Music Corp. 1942 Wait Till the Cows Come Home Ivan Caryll Anne Caldwell Chappell & Company Ltd 1917 Wait Till You Get Them Up In The Air, Boys Albert Von Tilzer Lew Brown EEW Broadway Music Corp. 1919 Waitin' for My Dearie Frederick Loewe Alan Jay Lerner Sam Fox Pub. Co. 1947 Waitin' for the Train to Come In Sunny Skylar Sunny Skylar Martin Block Music 1945 Waiting Harold Orlob Harry L. Cort Shapiro, Bernstein & Co. 1918 Waiting at the Church; or, My Wife Won't Let Me Henry E. Pether Fred W. Leigh Starmer Francis, Day & Hunter 1906 Waiting at the End of the Road Irving Berlin Irving Berlin Irving Berlin Inc. 1929 "Waiting for the Robert E. Lee" Lewis F. Muir L. Wolfe Gilbert F.A. Mills 1912 Waiting for the Robert E. Lee Lewis F. Muir L. Wolfe Gilbert Sigmund Spaeth Alfred Music Company 1939 Waiting in the Lobby of Your Heart Hank Thompson Hank Thompson Brenner Music Inc 1952 Wake The Town and Tell The People Jerry Livingston Sammy Gallop Joy Music Inc 1955 Wake Up, America! Jack Glogau George Graff Jr. -

The Many Faces of “Dinah”: a Prewar American Popular Song and the Lineage of Its Recordings in the U.S

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE The Many Faces of “Dinah” The Many Faces of “Dinah”: A Prewar American Popular Song and the Lineage of its Recordings in the U.S. and Japan Edgar W. Pope 「ダイナ」の多面性 ──戦前アメリカと日本における一つの流行歌とそのレコード── エドガー・W・ポープ 要 約 1925年にニューヨークで作曲された「ダイナ」は、1920・30年代のアメリ カと日本両国におけるもっとも人気のあるポピュラーソングの一つになり、 数多くのアメリカ人と日本人の演奏家によって録音された。本稿では、1935 年までに両国で録音されたこの曲のレコードのなかで、最も人気があり流 行したもののいくつかを選択して分析し比較する。さらにアメリカの演奏家 たちによって生み出された「ダイナ」の演奏習慣を表示する。そして日本人 の演奏家たちが、自分たちの想像力を通してこの曲の新しい理解を重ねる中 で、レコードを通して日本に伝わった演奏習慣をどのように応用していった かを考察する。 1. Introduction “Dinah,” published in 1925, was one of the leading hit songs to emerge from New York City’s “Tin Pan Alley” music industry during the interwar period, and was recorded in the U.S. by numerous singers and dance bands during the late 1920s and 1930s. It was also one of the most popular songs of the 1930s in Japan, where Japanese composers, arrangers, lyricists and performers, inspired in part by U.S. records, developed and recorded their own versions. In this paper I examine and compare a selection of the American and Japanese recordings of this song with the aim of tracing lines ─ 155 ─ 愛知県立大学外国語学部紀要第43号(言語・文学編) of influence, focusing on the aural evidence of the recordings themselves in relation to their recording and release dates. The analysis will show how American recordings of the song, which resulted from complex interactions of African American and European American artists and musical styles, established certain loose conventions of performance practices that were conveyed to Japan and to Japanese artists. It will then show how these Japanese artists made flexible use of American precedents, while also drawing influences from other Japanese recordings and adding their own individual creative ideas.