The Many Faces of “Dinah”: a Prewar American Popular Song and the Lineage of Its Recordings in the U.S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vocal Colour in Blue: Early Twentieth-Century Black Women Singers As Broadway's Voice Teachers

Document generated on 09/24/2021 8:30 p.m. Performance Matters Vocal Colour in Blue Early Twentieth-Century Black Women Singers as Broadway’s Voice Teachers Masi Asare Sound Acts, Part 1 Article abstract Volume 6, Number 2, 2020 This essay invokes a line of historical singing lessons that locate blues singers Bessie Smith and Ethel Waters in the lineage of Broadway belters. Contesting URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1075800ar the idea that black women who sang the blues and performed on the musical DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/1075800ar stage in the early twentieth century possessed “untrained” voices—a pervasive narrative that retains currency in present-day voice pedagogy literature—I See table of contents argue that singing is a sonic citational practice. In the act of producing vocal sound, one implicitly cites the vocal acts of the teacher from whom one has learned the song. And, I suggest, if performance is always “twice-behaved,” then the particular modes of doubleness present in voice point up this Publisher(s) citationality, a condition of vocal sound that I name the “twice-heard.” In Institute for Performance Studies, Simon Fraser University considering how vocal performances replicate and transmit knowledge, the “voice lesson” serves as a key site for analysis. My experiences as a voice coach and composer in New York City over two decades ground my approach of ISSN listening for the body in vocal sound. Foregrounding the perspective and 2369-2537 (digital) embodied experience of voice practitioners of colour, I critique the myth of the “natural belter” that obscures the lessons Broadway performers have drawn Explore this journal from the blueswomen’s sound. -

Fanning the Flames: Fandoms and Consumer Culture in Contemporary Japan

FANNING THE FLAMES Fans and Consumer Culture in Contemporary Japan Edited by William W. Kelly Fanning the Flames SUNY series in Japan in Transition Jerry Eades and Takeo Funabiki, editors Fanning the Flames Fans and Consumer Culture in Contemporary Japan EDITED BY WILLIAM W. K ELLY STATE UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK PRESS Published by State University of New York Press, Albany © 2004 State University of New York All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission. No part of this book may be stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means including electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the prior permission in writing of the publisher. For information, address State University of New York Press, 90 State Street, Suite 700, Albany, NY 12207 Production by Kelli Williams Marketing by Michael Campochiaro Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Fanning the f lames : fans and consumer culture in contemporary Japan / edited by William W. Kelly. p. cm. — (SUNY series in Japan in transition) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-7914-6031-2 (alk. paper) — ISBN 0-7914-6032-0 (pbk. : alk.paper) 1. Popular culture—Japan—History—20th century. I. Kelly, William W. II. Series. DS822.5b. F36 2004 306'.0952'09049—dc22 2004041740 10987654321 Contents List of Illustrations vii Acknowledgments ix Introduction: Locating the Fans 1 William W. Kelly 1 B-Boys and B-Girls: Rap Fandom and Consumer Culture in Japan 17 Ian Condry 2 Letters from the Heart: Negotiating Fan–Star Relationships in Japanese Popular Music 41 Christine R. -

CATALOGUE WELCOME to NAXOS JAZZ LEGENDS and NAXOS NOSTALGIA, Twin Compendiums Presenting the Best in Vintage Popular Music

NAXOS JAZZ LEGENDS/NOSTALGIA CATALOGUE WELCOME TO NAXOS JAZZ LEGENDS AND NAXOS NOSTALGIA, twin compendiums presenting the best in vintage popular music. Following in the footsteps of Naxos Historical, with its wealth of classical recordings from the golden age of the gramophone, these two upbeat labels put the stars of yesteryear back into the spotlight through glorious new restorations that capture their true essence as never before. NAXOS JAZZ LEGENDS documents the most vibrant period in the history of jazz, from the swinging ’20s to the innovative ’40s. Boasting a formidable roster of artists who forever changed the face of jazz, Naxos Jazz Legends focuses on the true giants of jazz, from the fathers of the early styles, to the queens of jazz vocalists and the great innovators of the 1940s and 1950s. NAXOS NOSTALGIA presents a similarly stunning line-up of all-time greats from the golden age of popular entertainment. Featuring the biggest stars of stage and screen performing some of the best- loved hits from the first half of the 20th century, this is a real treasure trove for fans to explore. RESTORING THE STARS OF THE PAST TO THEIR FORMER GLORY, by transforming old 78 rpm recordings into bright-sounding CDs, is an intricate task performed for Naxos by leading specialist producer-engineers using state-of-the-art-equipment. With vast personal collections at their disposal, as well as access to private and institutional libraries, they ensure that only the best available resources are used. The records are first cleaned using special equipment, carefully centred on a heavy-duty turntable, checked for the correct playing speed (often not 78 rpm), then played with the appropriate size of precision stylus. -

31 Days of Oscar® 2010 Schedule

31 DAYS OF OSCAR® 2010 SCHEDULE Monday, February 1 6:00 AM Only When I Laugh (’81) (Kevin Bacon, James Coco) 8:15 AM Man of La Mancha (’72) (James Coco, Harry Andrews) 10:30 AM 55 Days at Peking (’63) (Harry Andrews, Flora Robson) 1:30 PM Saratoga Trunk (’45) (Flora Robson, Jerry Austin) 4:00 PM The Adventures of Don Juan (’48) (Jerry Austin, Viveca Lindfors) 6:00 PM The Way We Were (’73) (Viveca Lindfors, Barbra Streisand) 8:00 PM Funny Girl (’68) (Barbra Streisand, Omar Sharif) 11:00 PM Lawrence of Arabia (’62) (Omar Sharif, Peter O’Toole) 3:00 AM Becket (’64) (Peter O’Toole, Martita Hunt) 5:30 AM Great Expectations (’46) (Martita Hunt, John Mills) Tuesday, February 2 7:30 AM Tunes of Glory (’60) (John Mills, John Fraser) 9:30 AM The Dam Busters (’55) (John Fraser, Laurence Naismith) 11:30 AM Mogambo (’53) (Laurence Naismith, Clark Gable) 1:30 PM Test Pilot (’38) (Clark Gable, Mary Howard) 3:30 PM Billy the Kid (’41) (Mary Howard, Henry O’Neill) 5:15 PM Mr. Dodd Takes the Air (’37) (Henry O’Neill, Frank McHugh) 6:45 PM One Way Passage (’32) (Frank McHugh, William Powell) 8:00 PM The Thin Man (’34) (William Powell, Myrna Loy) 10:00 PM The Best Years of Our Lives (’46) (Myrna Loy, Fredric March) 1:00 AM Inherit the Wind (’60) (Fredric March, Noah Beery, Jr.) 3:15 AM Sergeant York (’41) (Noah Beery, Jr., Walter Brennan) 5:30 AM These Three (’36) (Walter Brennan, Marcia Mae Jones) Wednesday, February 3 7:15 AM The Champ (’31) (Marcia Mae Jones, Walter Beery) 8:45 AM Viva Villa! (’34) (Walter Beery, Donald Cook) 10:45 AM The Pubic Enemy -

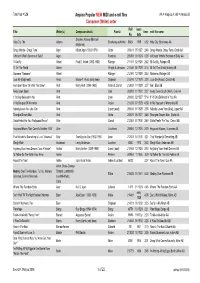

Ampico Popular NEW MIDI and E-Roll Files Composer

Total files = 536 Ampico Popular NEW MIDI and e-roll files AA = Ampico A, AB = Ampico B Composer (Writer) order Roll issue Title Writer(s) Composer details Pianist time midi file name No. date Stephen Adams (Michael Holy City, The Adams Brockway as Kmita 56824 1919 4:52 Holy City, Brockway AA Maybrick) Crazy Words - Crazy Tune Ager Milton Ager (1893-1979) Grofe 208611 05 1927 2:48 Crazy Words, Crazy Tune, Grofe AA I Wonder What's Become of Sally? Ager Fairchild 205191 09 1924 4:28 I Wonder What's Become of Sally AA I'll Get By Ahlert Fred E. Ahlert (1892-1953) Rainger 211171 02 1929 2:42 I'll Get By, Rainger AB I'll Tell The World Ahlert Wright & Johnston 211541 05 1929 3:14 I'll Tell The World (Ahlert) AB Marianne "Marianne" Ahlert Rainger 212191 12 1929 2:44 Marianne, Rainger AB Love Me (Deja) waltz Aivaz Morse-T. Aivaz (only item) Shipman 212241 12 1929 3:20 Love Me (Aivaz), Carroll AB Am I Blue? from "On With The Show" Akst Harry Akst (1894-1963) Arden & Carroll 212031 10 1929 3:37 Am I Blue AB Away Down South Akst Clair 203051 11 1922 2:37 Away Down South (Akst), Clair AA If I'd Only Believed In You Akst Lane 208383 02 1927 5:14 If I'd Only Believed In You AA In My Bouquet Of Memories Akst Arden 210233 07 1928 4:58 In My Bouquet of Memories AB Nobody Loves You Like I Do Akst Lopez (asst) 205531 01 1925 2:38 Nobody Loves You (Akst), Lopez AA Shanghai Dream Man Akst Grofe 208621 05 1927 3:48 Shanghai Dream Man, Grofe AA Gotta Feelin' For You "Hollywood Revue" Alter Carroll 212351 01 1930 2:49 Gotta Feelin' For You, Carroll AB Hugs and -

Lesson Plan Summary

Lesson Plan Summary Magic Tree House #42: A Good Night for Ghosts Scat-A-Dat-Do with Louis Armstrong FOCUS QUESTION: What contributions did Louis Armstrong make to the world of music? DURING THIS BOOK STUDY, COMMON CORE STANDARDS EACH STUDENT WILL: ADDRESSED: MUSIC AND VISUAL ARTS: Learn the definition and musical style Creative responses to texts of scat singing. Significant individuals Musical styles Practice scat singing. Write and perform an original line of READING: scat singing. Analyze texts for main idea and details. Comprehend the vocabulary of solo, duo, trio, and quartet. Summarize story parts. Read with fluency to support Study the biography of Louis comprehension. Armstrong WRITING: Record a main event and supporting Text types and purposes details of Louis Armstrong’s life. SPEAKING AND LISTENING: Present a project to the class. Comprehension and collaboration Presentation skills Respectful audience behavior 42-2S512 Created by: Melissa Summer Woodland Heights Elementary School, Spartanburg, South Carolina and Paula Cirillo, Hill Academy Moorpark, California Copyright © 2012, Mary Pope Osborne, Classroom Adventures Program, all rights reserved. Lesson Plan Magic Tree House #42: A Good Night for Ghosts Scat-a-dat-do with Louis Armstrong http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rT1Kuy922c0 DIRECTIONS: 1. INTRODUCE SCAT SINGING with Hoots the Owl at the link above. 2. DEFINE AS A CLASS: What is scat singing? 3. STUDY THE BIOGRAPHY of Louis Armstrong, who was famous for his scat singing. Students can choose to work in one of the following ensembles: SOLO (alone) DUO (with a partner) TRIO (in a group of three) QUARTET (in a group of four) Students will work in their ensembles to summarize the main ideas in a reading about Louis Armstrong’s life. -

Selected Observations from the Harlem Jazz Scene By

SELECTED OBSERVATIONS FROM THE HARLEM JAZZ SCENE BY JONAH JONATHAN A dissertation submitted to the Graduate School-Newark Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Graduate Program in Jazz History and Research Written under the direction of Dr. Lewis Porter and approved by ______________________ ______________________ Newark, NJ May 2015 2 Table of Contents Acknowledgements Page 3 Abstract Page 4 Preface Page 5 Chapter 1. A Brief History and Overview of Jazz in Harlem Page 6 Chapter 2. The Harlem Race Riots of 1935 and 1943 and their relationship to Jazz Page 11 Chapter 3. The Harlem Scene with Radam Schwartz Page 30 Chapter 4. Alex Layne's Life as a Harlem Jazz Musician Page 34 Chapter 5. Some Music from Harlem, 1941 Page 50 Chapter 6. The Decline of Jazz in Harlem Page 54 Appendix A historic list of Harlem night clubs Page 56 Works Cited Page 89 Bibliography Page 91 Discography Page 98 3 Acknowledgements This thesis is dedicated to all of my teachers and mentors throughout my life who helped me learn and grow in the world of jazz and jazz history. I'd like to thank these special people from before my enrollment at Rutgers: Andy Jaffe, Dave Demsey, Mulgrew Miller, Ron Carter, and Phil Schaap. I am grateful to Alex Layne and Radam Schwartz for their friendship and their willingness to share their interviews in this thesis. I would like to thank my family and loved ones including Victoria Holmberg, my son Lucas Jonathan, my parents Darius Jonathan and Carrie Bail, and my sisters Geneva Jonathan and Orelia Jonathan. -

Jazz and the Cultural Transformation of America in the 1920S

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2003 Jazz and the cultural transformation of America in the 1920s Courtney Patterson Carney Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Carney, Courtney Patterson, "Jazz and the cultural transformation of America in the 1920s" (2003). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 176. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/176 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. JAZZ AND THE CULTURAL TRANSFORMATION OF AMERICA IN THE 1920S A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of History by Courtney Patterson Carney B.A., Baylor University, 1996 M.A., Louisiana State University, 1998 December 2003 For Big ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The real truth about it is no one gets it right The real truth about it is we’re all supposed to try1 Over the course of the last few years I have been in contact with a long list of people, many of whom have had some impact on this dissertation. At the University of Chicago, Deborah Gillaspie and Ray Gadke helped immensely by guiding me through the Chicago Jazz Archive. -

Vocal Jazz in the Choral Classroom: a Pedagogical Study

University of Northern Colorado Scholarship & Creative Works @ Digital UNC Dissertations Student Research 5-2019 Vocal Jazz in the Choral Classroom: A Pedagogical Study Lara Marie Moline Follow this and additional works at: https://digscholarship.unco.edu/dissertations Recommended Citation Moline, Lara Marie, "Vocal Jazz in the Choral Classroom: A Pedagogical Study" (2019). Dissertations. 576. https://digscholarship.unco.edu/dissertations/576 This Text is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research at Scholarship & Creative Works @ Digital UNC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholarship & Creative Works @ Digital UNC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. © 2019 LARA MARIE MOLINE ALL RIGHTS RESERVED UNIVERSITY OF NORTHERN COLORADO Greeley, Colorado The Graduate School VOCAL JAZZ IN THE CHORAL CLASSROOM: A PEDAGOGICAL STUDY A DIssertatIon SubMItted In PartIal FulfIllment Of the RequIrements for the Degree of Doctor of Arts Lara Marie MolIne College of Visual and Performing Arts School of Music May 2019 ThIs DIssertatIon by: Lara Marie MolIne EntItled: Vocal Jazz in the Choral Classroom: A Pedagogical Study has been approved as meetIng the requIrement for the Degree of Doctor of Arts in College of VIsual and Performing Arts In School of Music, Program of Choral ConductIng Accepted by the Doctoral CoMMIttee _________________________________________________ Galen Darrough D.M.A., ChaIr _________________________________________________ Jill Burgett D.A., CoMMIttee Member _________________________________________________ Michael Oravitz Ph.D., CoMMIttee Member _________________________________________________ Michael Welsh Ph.D., Faculty RepresentatIve Date of DIssertatIon Defense________________________________________ Accepted by the Graduate School ________________________________________________________ LInda L. Black, Ed.D. Associate Provost and Dean Graduate School and InternatIonal AdMIssions Research and Sponsored Projects ABSTRACT MolIne, Lara Marie. -

Institute for Studies in American Music Conservatory of Music, Brooklyn College of the City University of New York NEWSLETTER Volume XXXIV, No

Institute for Studies In American Music Conservatory of Music, Brooklyn College of the City University of New York NEWSLETTER Volume XXXIV, No. 2 Spring 2005 Jungle Jive: Jazz was an integral element in the sound and appearance of animated cartoons produced in Race, Jazz, Hollywood from the late 1920s through the late 1950s.1 Everything from big band to free jazz and Cartoons has been featured in cartoons, either as the by soundtrack to a story or the basis for one. The studio run by the Fleischer brothers took an Daniel Goldmark unusual approach to jazz in the late 1920s and the 1930s, treating it not as background but as a musical genre deserving of recognition. Instead of using jazz idioms merely to color the musical score, their cartoons featured popular songs by prominent recording artists. Fleischer was a well- known studio in the 1920s, perhaps most famous Louis Armstrong in the jazz cartoon I’ll Be Glad When for pioneering the sing-along cartoon with the You’ re Dead, You Rascal You (Fleischer, 1932) bouncing ball in Song Car-Tunes. An added attraction to Fleischer cartoons was that Paramount Pictures, their distributor and parent company, allowed the Fleischers to use its newsreel recording facilities, where they were permitted to film famous performers scheduled to appear in Paramount shorts and films.2 Thus, a wide variety of musicians, including Ethel Merman, Rudy Vallee, the Mills Brothers, Gus Edwards, the Boswell Sisters, Cab Calloway, and Louis Armstrong, began appearing in Fleischer cartoons. This arrangement benefited both the studios and the stars. -

LEGISLATIVE RESOLUTION Commemorating the 96Th Birthday of Ella Fitzger- Ald and Her Tremendous Contributions to Jazz

LEGISLATIVE RESOLUTION commemorating the 96th birthday of Ella Fitzger- ald and her tremendous contributions to jazz WHEREAS, It is the sense of this Legislative Body to recognize and commend those musical geniuses who brought entertainment and cultural enrichment to the citizens of the great Empire State; and WHEREAS, Also known as the "First Lady of Song", "Queen of Jazz", and "Lady Ella", Ella Fitzgerald was an American jazz vocalist noted for her purity of tone, impeccable diction, phrasing and intonation, and a "horn-like" improvisational ability, particularly her scat singing; she was a notable interpreter of the Great American Songbook; and WHEREAS, Ella Fitzgerald was born on April 25, 1917, in Newport News, Virginia, the daughter of Temperance "Tempie" and William Fitzgerald; her parents separated soon after her birth, and Ella and her mother went to Yonkers, New York; she and her family were Methodists and were active in the Bethany African Methodist Episcopal Church; and WHEREAS, In her youth, Ella Fitzgerald wanted to be a dancer, although she loved listening to jazz recordings by Louis Armstrong, Bing Crosby and The Boswell Sisters, and idolized lead singer Connee Boswell; after the death of her mother in 1932 and overcoming many hardships and obsta- cles, a young Ella made her singing debut at age 17 on November 21, 1934, at the Apollo Theater in Harlem, New York and the rest was histo- ry; and WHEREAS, Over the course of her 59-year recording career, the First Lady of Song sold 40 million copies of her 70-plus albums, won 13 Grammy Awards and was awarded the National Medal of Arts by former president Ronald Reagan and the Presidential Medal of Freedom by former president George H. -

“PRESENCE” of JAPAN in KOREA's POPULAR MUSIC CULTURE by Eun-Young Ju

TRANSNATIONAL CULTURAL TRAFFIC IN NORTHEAST ASIA: THE “PRESENCE” OF JAPAN IN KOREA’S POPULAR MUSIC CULTURE by Eun-Young Jung M.A. in Ethnomusicology, Arizona State University, 2001 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2007 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Eun-Young Jung It was defended on April 30, 2007 and approved by Richard Smethurst, Professor, Department of History Mathew Rosenblum, Professor, Department of Music Andrew Weintraub, Associate Professor, Department of Music Dissertation Advisor: Bell Yung, Professor, Department of Music ii Copyright © by Eun-Young Jung 2007 iii TRANSNATIONAL CULTURAL TRAFFIC IN NORTHEAST ASIA: THE “PRESENCE” OF JAPAN IN KOREA’S POPULAR MUSIC CULTURE Eun-Young Jung, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2007 Korea’s nationalistic antagonism towards Japan and “things Japanese” has mostly been a response to the colonial annexation by Japan (1910-1945). Despite their close economic relationship since 1965, their conflicting historic and political relationships and deep-seated prejudice against each other have continued. The Korean government’s official ban on the direct import of Japanese cultural products existed until 1997, but various kinds of Japanese cultural products, including popular music, found their way into Korea through various legal and illegal routes and influenced contemporary Korean popular culture. Since 1998, under Korea’s Open- Door Policy, legally available Japanese popular cultural products became widely consumed, especially among young Koreans fascinated by Japan’s quintessentially postmodern popular culture, despite lingering resentments towards Japan.