Vocal Jazz in the Choral Classroom: a Pedagogical Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

E~:U;;; Tage of Alcohol, Penoza Road by DEBBIE FRANKEL from the Lottery for Traditional and Pencader Said

University of Delaware, Newark, DE Friday, April10, 1981 Pro.cessing to begin on financial aid forms as House compromises By BRENDA GREENBERG will be less likely to receive The freeze that had been as much,'' Rogers said. placed on processing Pell A payment schedule (the Grant applications has been guidelines for the university lifted, and processing is to establish the student index scheduled to begin April 17, of eligibility) has not yet been according to Jerry Rogers, issued by the federal govern associate director of financial ment, Rogers said. aid. \ "As soon as we receive this Rogers said that Represen payment schedule we can tative Paul Simon (D-Ill.), start the processing and start chairman of the House issuing award notifications," postsecondary educational Rogers said. "We hope to committee, announced last start notifying students by week that a compromise has June." been reached between the Of the 3,000 university committee and the Reagan students now receiving the administration. They have Pell Grants, 500 come from decided to eliminate infla families with incomes of tionary adjustments, $25,000 or more, said Michael previously a factor in Lee, assistant director of calculating the amount that financial aid, at a March 26 families are expected to con program, "Reagan's Budget tribute to their children's col Cuts," sponsored by Kappa CONCERN for the ever-growing number of murdered black children in Atlanta is widespread lege costs. Alpha Psi fraternity. on campus, as evidenced by this banner hung by Kappa Alpha Psi fraternity. Simon also said the amount of the Pell Grant awards, Proposals to modify the (formerly the Basic Educa Guaranteed Student Loan tional Opportunity Grant), (GSL) program are not an Moonshine equipment confiscated which varies from $200 to ticipated to be in effect before By LORRI PIVINSKI Matthew Phillips (EG84) and While making routine $1,750, will not increase next October, Rogers said. -

Cds by Composer/Performer

CPCC MUSIC LIBRARY COMPACT DISCS Updated May 2007 Abercrombie, John (Furs on Ice and 9 other selections) guitar, bass, & synthesizer 1033 Academy for Ancient Music Berlin Works of Telemann, Blavet Geminiani 1226 Adams, John Short Ride, Chairman Dances, Harmonium (Andriessen) 876, 876A Adventures of Baron Munchausen (music composed and conducted by Michael Kamen) 1244 Adderley, Cannonball Somethin’ Else (Autumn Leaves; Love For Sale; Somethin’ Else; One for Daddy-O; Dancing in the Dark; Alison’s Uncle 1538 Aebersold, Jamey: Favorite Standards (vol 22) 1279 pt. 1 Aebersold, Jamey: Favorite Standards (vol 22) 1279 pt. 2 Aebersold, Jamey: Gettin’ It Together (vol 21) 1272 pt. 1 Aebersold, Jamey: Gettin’ It Together (vol 21) 1272 pt. 2 Aebersold, Jamey: Jazz Improvisation (vol 1) 1270 Aebersold, Jamey: Major and Minor (vol 24) 1281 pt. 1 Aebersold, Jamey: Major and Minor (vol 24) 1281 pt. 2 Aebersold, Jamey: One Dozen Standards (vol 23) 1280 pt. 1 Aebersold, Jamey: One Dozen Standards (vol 23) 1280 pt. 2 Aebersold, Jamey: The II-V7-1 Progression (vol 3) 1271 Aerosmith Get a Grip 1402 Airs d’Operettes Misc. arias (Barbara Hendricks; Philharmonia Orch./Foster) 928 Airwaves: Heritage of America Band, U.S. Air Force/Captain Larry H. Lang, cond. 1698 Albeniz, Echoes of Spain: Suite Espanola, Op.47 and misc. pieces (John Williams, guitar) 962 Albinoni, Tomaso (also Pachelbel, Vivaldi, Bach, Purcell) 1212 Albinoni, Tomaso Adagio in G Minor (also Pachelbel: Canon; Zipoli: Elevazione for Cello, Oboe; Gluck: Dance of the Furies, Dance of the Blessed Spirits, Interlude; Boyce: Symphony No. 4 in F Major; Purcell: The Indian Queen- Trumpet Overture)(Consort of London; R,Clark) 1569 Albinoni, Tomaso Concerto Pour 2 Trompettes in C; Concerto in C (Lionel Andre, trumpet) (also works by Tartini; Vivaldi; Maurice André, trumpet) 1520 Alderete, Ignacio: Harpe indienne et orgue 1019 Aloft: Heritage of America Band (United States Air Force/Captain Larry H. -

The Solo Style of Jazz Clarinetist Johnny Dodds: 1923 – 1938

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2003 The solo ts yle of jazz clarinetist Johnny Dodds: 1923 - 1938 Patricia A. Martin Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Martin, Patricia A., "The os lo style of jazz clarinetist Johnny Dodds: 1923 - 1938" (2003). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 1948. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/1948 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. THE SOLO STYLE OF JAZZ CLARINETIST JOHNNY DODDS: 1923 – 1938 A Monograph Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College In partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in The School of Music By Patricia A.Martin B.M., Eastman School of Music, 1984 M.M., Michigan State University, 1990 May 2003 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This is dedicated to my father and mother for their unfailing love and support. This would not have been possible without my father, a retired dentist and jazz enthusiast, who infected me with his love of the art form and led me to discover some of the great jazz clarinetists. In addition I would like to thank Dr. William Grimes, Dr. Wallace McKenzie, Dr. Willis Delony, Associate Professor Steve Cohen and Dr. -

Mesia Austin, Percussion Received Much of the Recognition Due a Venerable Jazz Icon

and Blo win' The Blues Away (1959), which includes his famous, "Sister Sadie." He also combined jazz with a sassy take on pop through the 1961 hit, "Filthy McNasty." As social and cultural upheavals shook the nation during the late 1960s and early 1970s, Silver responded to these changes through music. He commented directly on the new scene through a trio of records called United States of Mind (1970-1972) that featured the spirited vocals of Andy Bey. The composer got deeper into cosmic philosophy as his group, Silver 'N Strings, recorded Silver 'N Strings School of Music Play The Music of the Spheres (1979). After Silver's long tenure with Blue Note ended, he continued to presents create vital music. The 1985 album, Continuity of Spirit (Silveto), features his unique orchestral collaborations. In the 1990s, Silver directly answered the urban popular music that had been largely built from his influence on It's Got To Be Funky (Columbia, 1993). On Jazz Has A Sense of Humor (Verve, 1998), he shows his younger SENIOR RECITAL group of sidemen the true meaning of the music. Now living surrounded by a devoted family in California, Silver has Mesia Austin, percussion received much of the recognition due a venerable jazz icon. In 2005, the National Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences (NARAS) gave him its President's Merit Award. Silver is also anxious to tell the Theresa Stephens, clarinet Brian Palat, percussion world his life story in his own words as he just released his autobiography, Let's Get To The Nitty Gritty. -

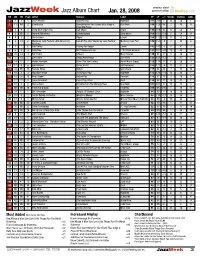

Jazzweek Jazz Album Chart Jan

airplay data JazzWeek Jazz Album Chart Jan. 28, 2008 powered by TW LW 2W Peak Artist Release Label TP LP +/- Weeks Stations Adds 1 1 1 1 Steve Nelson Sound-Effect HighNote 211 210 1 13 56 1 2 11 NR 2 Eliane Elias Something For You: Eliane Elias Sings & Blue Note 196 128 68 2 49 14 Plays Bill Evans 3 5 9 2 Deep Blue Organ Trio Folk Music Origin 194 169 25 15 52 1 4 2 NR 2 Hendrik Meurkens Sambatropolis Zoho Music 166 185 -19 2 54 13 5 4 2 2 Jim Snidero Tippin’ Savant 154 172 -18 11 53 1 6 6 33 6 Monterey Jazz Festival 50th Aniversary Live At The 2007 Monterey Jazz Festival Monterey Jazz Fest 145 154 -9 3 43 8 All-Stars 7 7 7 6 Bob DeVos Playing For Keeps Savant 142 145 -3 11 47 0 8 3 5 3 Andy Bey Ain’t Necessarily So 12th Street Records 137 182 -45 10 49 0 9 20 34 9 Ron Blake Shayari Mack Avenue 136 94 42 3 46 11 10 7 14 7 Joe Locke Sticks And Strings Jazz Eyes 132 145 -13 7 37 5 11 14 11 2 Herbie Hancock River: The Joni Letters Verve Music Group 125 114 11 17 50 0 12 12 8 8 John Brown Terms Of Art Self Released 123 127 -4 11 32 0 13 28 NR 13 Pamela Hines Return Spice Rack 117 84 33 2 43 14 14 10 3 3 Houston Person Thinking Of You HighNote 115 139 -24 13 38 2 15 18 38 15 Brad Goode Nature Boy Delmark 112 97 15 3 29 6 16 22 21 3 Cyrus Chestnut Cyrus Plays Elvis Koch 110 93 17 16 37 1 17 16 6 6 Stacey Kent Breakfast On The Morning Tram Blue Note 101 101 0 16 33 0 18 NR NR 18 Frank Kimbrough Air Palmetto 100 NR 100 1 36 31 19 24 11 1 Eric Alexander Temple Of Olympic Zeus HighNote 94 90 4 18 39 0 20 15 4 2 Gerald Wilson Orchestra Monterey -

Sing It and Swing It ! Incorporating Vocal Jazz Into Your Choral Program Presented by April Tini MSVMA Summer Workshop 2018

Sing It and Swing It ! Incorporating vocal jazz into your choral program Presented by April Tini MSVMA Summer Workshop 2018 ELEMENTS OF A SUCCESSFUL VOCAL JAZZ PROGRAM: The vocal ensemble - auditions, size of group, parts/voicing, sound, style Repertoire The rehearsal and preparation process The sound system The rhythm section The jazz soloist Improvisation Targeted Listening TODAY’S WORKSHOP DEMO VOCAL EXAMPLES: VJ Warmups, swing feel, straight tone, soloist, improv basics VOCAL JAZZ EVENTS AND EXPERTS THROUGHOUT THE STATE: • MDJW - Metro Detroit Jazz Workshop/Vocal Workshop - Detroit, July 2019; www.helpwithjazz.com or facebook page. Scott Gwinell, Director • Michigan Jazz Festival - July 2019, Schoolcraft College; 7 stages, live jazz, free • Detroit Jazz Festival - Labor Day Weekend, Downtown Detroit Rivefront • DJF Youth Vocal Competition - Detroit Jazz Festival Affiliation; for your soloists! • Detroit Music Hall - Regular Sunday night jam sessions, 6 PM, led by Scott Gwinell • Detroit Music Hall Educational Outreach Program - clinicians available to come to your school and offer workshops, masterclasses www.musichall.org • GCIVJF - Gold Company Invitational Vocal Jazz Festival, Greg Jasperse, director, March 2019, annually; exceptional vje experience for students and teachers • CLINICIANS to help your students (within our state): Duane Davis - Grand Rapids area Jed Scott - Grand Rapids, Grand Rapids Community College Greg Jasperes - Kalamazoo, WMU Gold Company Sunny Wilkinson - East Lansing area Scott Gwinell - Detroit area and -

February 4, 2020 (XL:2) Lloyd Bacon: 42ND STREET (1933, 89M) the Version of This Goldenrod Handout Sent out in Our Monday Mailing, and the One Online, Has Hot Links

February 4, 2020 (XL:2) Lloyd Bacon: 42ND STREET (1933, 89m) The version of this Goldenrod Handout sent out in our Monday mailing, and the one online, has hot links. Spelling and Style—use of italics, quotation marks or nothing at all for titles, e.g.—follows the form of the sources. DIRECTOR Lloyd Bacon WRITING Rian James and James Seymour wrote the screenplay with contributions from Whitney Bolton, based on a novel by Bradford Ropes. PRODUCER Darryl F. Zanuck CINEMATOGRAPHY Sol Polito EDITING Thomas Pratt and Frank Ware DANCE ENSEMBLE DESIGN Busby Berkeley The film was nominated for Best Picture and Best Sound at the 1934 Academy Awards. In 1998, the National Film Preservation Board entered the film into the National Film Registry. CAST Warner Baxter...Julian Marsh Bebe Daniels...Dorothy Brock George Brent...Pat Denning Knuckles (1927), She Couldn't Say No (1930), A Notorious Ruby Keeler...Peggy Sawyer Affair (1930), Moby Dick (1930), Gold Dust Gertie (1931), Guy Kibbee...Abner Dillon Manhattan Parade (1931), Fireman, Save My Child Una Merkel...Lorraine Fleming (1932), 42nd Street (1933), Mary Stevens, M.D. (1933), Ginger Rogers...Ann Lowell Footlight Parade (1933), Devil Dogs of the Air (1935), Ned Sparks...Thomas Barry Gold Diggers of 1937 (1936), San Quentin (1937), Dick Powell...Billy Lawler Espionage Agent (1939), Knute Rockne All American Allen Jenkins...Mac Elroy (1940), Action, the North Atlantic (1943), The Sullivans Edward J. Nugent...Terry (1944), You Were Meant for Me (1948), Give My Regards Robert McWade...Jones to Broadway (1948), It Happens Every Spring (1949), The George E. -

Why Jazz Still Matters Jazz Still Matters Why Journal of the American Academy of Arts & Sciences Journal of the American Academy

Dædalus Spring 2019 Why Jazz Still Matters Spring 2019 Why Dædalus Journal of the American Academy of Arts & Sciences Spring 2019 Why Jazz Still Matters Gerald Early & Ingrid Monson, guest editors with Farah Jasmine Griffin Gabriel Solis · Christopher J. Wells Kelsey A. K. Klotz · Judith Tick Krin Gabbard · Carol A. Muller Dædalus Journal of the American Academy of Arts & Sciences “Why Jazz Still Matters” Volume 148, Number 2; Spring 2019 Gerald Early & Ingrid Monson, Guest Editors Phyllis S. Bendell, Managing Editor and Director of Publications Peter Walton, Associate Editor Heather M. Struntz, Assistant Editor Committee on Studies and Publications John Mark Hansen, Chair; Rosina Bierbaum, Johanna Drucker, Gerald Early, Carol Gluck, Linda Greenhouse, John Hildebrand, Philip Khoury, Arthur Kleinman, Sara Lawrence-Lightfoot, Alan I. Leshner, Rose McDermott, Michael S. McPherson, Frances McCall Rosenbluth, Scott D. Sagan, Nancy C. Andrews (ex officio), David W. Oxtoby (ex officio), Diane P. Wood (ex officio) Inside front cover: Pianist Geri Allen. Photograph by Arne Reimer, provided by Ora Harris. © by Ross Clayton Productions. Contents 5 Why Jazz Still Matters Gerald Early & Ingrid Monson 13 Following Geri’s Lead Farah Jasmine Griffin 23 Soul, Afrofuturism & the Timeliness of Contemporary Jazz Fusions Gabriel Solis 36 “You Can’t Dance to It”: Jazz Music and Its Choreographies of Listening Christopher J. Wells 52 Dave Brubeck’s Southern Strategy Kelsey A. K. Klotz 67 Keith Jarrett, Miscegenation & the Rise of the European Sensibility in Jazz in the 1970s Gerald Early 83 Ella Fitzgerald & “I Can’t Stop Loving You,” Berlin 1968: Paying Homage to & Signifying on Soul Music Judith Tick 92 La La Land Is a Hit, but Is It Good for Jazz? Krin Gabbard 104 Yusef Lateef’s Autophysiopsychic Quest Ingrid Monson 115 Why Jazz? South Africa 2019 Carol A. -

Jazz and the Cultural Transformation of America in the 1920S

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2003 Jazz and the cultural transformation of America in the 1920s Courtney Patterson Carney Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Carney, Courtney Patterson, "Jazz and the cultural transformation of America in the 1920s" (2003). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 176. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/176 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. JAZZ AND THE CULTURAL TRANSFORMATION OF AMERICA IN THE 1920S A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of History by Courtney Patterson Carney B.A., Baylor University, 1996 M.A., Louisiana State University, 1998 December 2003 For Big ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The real truth about it is no one gets it right The real truth about it is we’re all supposed to try1 Over the course of the last few years I have been in contact with a long list of people, many of whom have had some impact on this dissertation. At the University of Chicago, Deborah Gillaspie and Ray Gadke helped immensely by guiding me through the Chicago Jazz Archive. -

BROWNIE the Complete Emarcy Recordings of Clifford Brown Including Newly Discovered Essential Material from the Legendary Clifford Brown – Max Roach Quintet

BROWNIE The Complete Emarcy Recordings of Clifford Brown Including Newly Discovered Essential Material from the Legendary Clifford Brown – Max Roach Quintet Dan Morgenstern Grammy Award for Best Album Notes 1990 Disc 1 1. DELILAH 8:04 Clifford Brown-Max RoaCh Quintet: (V. Young) Clifford Brown (tp), Harold Land (ts), Richie 2. DARN THAT DREAM 4:02 Powell (p), George Morrow (b), Max RoaCh (De Lange - V. Heusen) (ds) 3. PARISIAN THOROUGHFARE 7:16 (B. Powell) 4. JORDU 7:43 (D. Jordan) 5. SWEET CLIFFORD 6:40 (C. Brown) 6. SWEET CLIFFORD (CLIFFORD’S FANTASY)* 1:45 1~3: Los Angeles, August 2, 1954 (C. Brown) 7. I DON’T STAND A GHOST OF A CHANCE* 3:03 4~8: Los Angeles, August 3, 1954 (Crosby - Washington - Young) 8. I DON’ T STAND A GHOST OF A CHANC E 7:19 9~12: Los Angeles, August 5, 1954 (Crosby - Washington - Young) 9. STOMPIN’ AT TH E SAVOY 6:24 (Goodman - Sampson - Razaf - Webb) 10. I GET A KICK OUT OF YOU 7:36 (C. Porter) 11. I GET A KICK OUT OF YOU* 8:29 * Previously released alternate take (C. Porter) 12. I’ LL STRING ALONG WITH YOU 4:10 (Warren - Dubin) Disc 2 1. JOY SPRING* 6:44 (C. Brown) Clifford Brown-Max RoaCh Quintet: 2. JOY SPRING 6:49 (C. Brown) Clifford Brown (tp), Harold Land (ts), Richie 3. MILDAMA* 3:33 (M. Roach) Powell (p), George Morrow (b), Max RoaCh (ds) 4. MILDAMA* 3:22 (M. Roach) Los Angeles, August 6, 1954 5. MILDAMA* 3:55 (M. Roach) 6. -

Southern Black Gospel Music: Qualitative Look at Quartet Sound

LIBERTY UNIVERSITY SOUTHERN BLACK GOSPEL MUSIC: QUALITATIVE LOOK AT QUARTET SOUND DURING THE GOSPEL ‘BOOM’ PERIOD OF 1940-1960 A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE SCHOOL OF MUSIC IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN ETHNOMUSICOLOGY BY BEATRICE IRENE PATE LYNCHBURG, V.A. April 2014 1 Abstract The purpose of this work is to identify features of southern black gospel music, and to highlight what makes the music unique. One goal is to present information about black gospel music and distinguishing the different definitions of gospel through various ages of gospel music. A historical accounting for the gospel music is necessary, to distinguish how the different definitions of gospel are from other forms of gospel music during different ages of gospel. The distinctions are important for understanding gospel music and the ‘Southern’ gospel music distinction. The quartet sound was the most popular form of music during the Golden Age of Gospel, a period in which there was significant growth of public consumption of Black gospel music, which was an explosion of black gospel culture, hence the term ‘gospel boom.’ The gospel boom period was from 1940 to 1960, right after the Great Depression, a period that also included World War II, and right before the Civil Rights Movement became a nationwide movement. This work will evaluate the quartet sound during the 1940’s, 50’s, and 60’s, which will provide a different definition for gospel music during that era. Using five black southern gospel quartets—The Dixie Hummingbirds, The Fairfield Four, The Golden Gate Quartet, The Soul Stirrers, and The Swan Silvertones—to define what southern black gospel music is, its components, and to identify important cultural elements of the music. -

Institute for Studies in American Music Conservatory of Music, Brooklyn College of the City University of New York NEWSLETTER Volume XXXIV, No

Institute for Studies In American Music Conservatory of Music, Brooklyn College of the City University of New York NEWSLETTER Volume XXXIV, No. 2 Spring 2005 Jungle Jive: Jazz was an integral element in the sound and appearance of animated cartoons produced in Race, Jazz, Hollywood from the late 1920s through the late 1950s.1 Everything from big band to free jazz and Cartoons has been featured in cartoons, either as the by soundtrack to a story or the basis for one. The studio run by the Fleischer brothers took an Daniel Goldmark unusual approach to jazz in the late 1920s and the 1930s, treating it not as background but as a musical genre deserving of recognition. Instead of using jazz idioms merely to color the musical score, their cartoons featured popular songs by prominent recording artists. Fleischer was a well- known studio in the 1920s, perhaps most famous Louis Armstrong in the jazz cartoon I’ll Be Glad When for pioneering the sing-along cartoon with the You’ re Dead, You Rascal You (Fleischer, 1932) bouncing ball in Song Car-Tunes. An added attraction to Fleischer cartoons was that Paramount Pictures, their distributor and parent company, allowed the Fleischers to use its newsreel recording facilities, where they were permitted to film famous performers scheduled to appear in Paramount shorts and films.2 Thus, a wide variety of musicians, including Ethel Merman, Rudy Vallee, the Mills Brothers, Gus Edwards, the Boswell Sisters, Cab Calloway, and Louis Armstrong, began appearing in Fleischer cartoons. This arrangement benefited both the studios and the stars.