Liner Notes, Visit Our Web Site

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

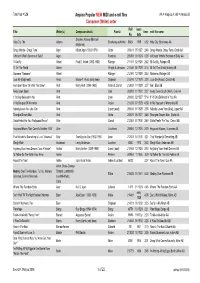

Ampico Popular NEW MIDI and E-Roll Files Composer

Total files = 536 Ampico Popular NEW MIDI and e-roll files AA = Ampico A, AB = Ampico B Composer (Writer) order Roll issue Title Writer(s) Composer details Pianist time midi file name No. date Stephen Adams (Michael Holy City, The Adams Brockway as Kmita 56824 1919 4:52 Holy City, Brockway AA Maybrick) Crazy Words - Crazy Tune Ager Milton Ager (1893-1979) Grofe 208611 05 1927 2:48 Crazy Words, Crazy Tune, Grofe AA I Wonder What's Become of Sally? Ager Fairchild 205191 09 1924 4:28 I Wonder What's Become of Sally AA I'll Get By Ahlert Fred E. Ahlert (1892-1953) Rainger 211171 02 1929 2:42 I'll Get By, Rainger AB I'll Tell The World Ahlert Wright & Johnston 211541 05 1929 3:14 I'll Tell The World (Ahlert) AB Marianne "Marianne" Ahlert Rainger 212191 12 1929 2:44 Marianne, Rainger AB Love Me (Deja) waltz Aivaz Morse-T. Aivaz (only item) Shipman 212241 12 1929 3:20 Love Me (Aivaz), Carroll AB Am I Blue? from "On With The Show" Akst Harry Akst (1894-1963) Arden & Carroll 212031 10 1929 3:37 Am I Blue AB Away Down South Akst Clair 203051 11 1922 2:37 Away Down South (Akst), Clair AA If I'd Only Believed In You Akst Lane 208383 02 1927 5:14 If I'd Only Believed In You AA In My Bouquet Of Memories Akst Arden 210233 07 1928 4:58 In My Bouquet of Memories AB Nobody Loves You Like I Do Akst Lopez (asst) 205531 01 1925 2:38 Nobody Loves You (Akst), Lopez AA Shanghai Dream Man Akst Grofe 208621 05 1927 3:48 Shanghai Dream Man, Grofe AA Gotta Feelin' For You "Hollywood Revue" Alter Carroll 212351 01 1930 2:49 Gotta Feelin' For You, Carroll AB Hugs and -

Hello! My Baby Student Guide.Pdf

Goodspeed’s Student Guide to the Theatre is made possible through the generosity of GOODSPEED MUSICALS GOODSPEED GUIDE TO THE THEATRE Student The Max Showalter Center for Education in Musical Theatre HELLO! MY BABY The Norma Terris Theatre November 3 - 27, 2011 _________ CONCEIVED & WRITTEN BY CHERI STEINKELLNER NEW LYRICS BY CHERI STEINKELLNER Student Guide to the Theatre TABLE OF CONTENTS NEW MUSIC & ARRANGEMENTS BY GEORGIA STITT ABOUT THE SHOW: The Story...................………………………………………….3 LIGHTING DESIGN BY JOHN LASITER ABOUT THE SHOW: The Characters...........................……………………………5 ABOUT THE SHOW: The Writers....................…..…………………………………...6 COSTUME DESIGN BY ROBIN L. McGEE Listen Up: Tin Pan Alley Tunes................………………………………................7 SCENIC DESIGN BY A Few Composers + Lyricists..............................……………………………….....8 MICHAEL SCHWEIKARDT Welcome to the Alley!...............…………………………………………………...10 CHOREOGRAPHED BY Breaking into the Boys Club......…………………………………………………...11 KELLI BARCLAY New York City..............................…………………………………………………...12 DIRECTED BY RAY RODERICK FUN AND GAMES: Word Search........................................................................13 FUN AND GAMES: Crossword Puzzle….……………………………...................14 PRODUCED FOR GOODSPEED MUSICALS BY How To Be An Awesome Audience Member…………………......................15 MICHAEL P. PRICE The Student Guide to the Theatre for Hello! My Baby was prepared by Joshua S. Ritter M.F.A, Education & Library Director and Christine Hopkins, -

Student Guide Table of Contents

GOODSPEED MUSICALS STUDENT GUIDE TABLE OF CONTENTS APRIL 13 - JUNE 21, 2018 THE GOODSPEED Production History.................................................................................................................................................................................3 Synopsis.......................................................................................................................................................................................................4 Characters......................................................................................................................................................................................................5 Meet the Writers.....................................................................................................................................................................................6 Meet the Creative Team........................................................................................................................................................................8 Presents for Mrs. Rogers......................................................................................................................................................................9 Will Rogers..............................................................................................................................................................................................11 Wiley Post, Aviation Marvel..............................................................................................................................................................16 -

Chronology and Itinerary of the Career of J. Tim Brymn Materials for a Biography Peter M

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Faculty Publications: School of Music Music, School of 8-26-2016 Chronology and Itinerary of the Career of J. Tim Brymn Materials for a Biography Peter M. Lefferts University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/musicfacpub Part of the African American Studies Commons, American Popular Culture Commons, and the Music Commons Lefferts, Peter M., "Chronology and Itinerary of the Career of J. Tim Brymn Materials for a Biography" (2016). Faculty Publications: School of Music. 64. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/musicfacpub/64 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Music, School of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications: School of Music by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. 1 08/26/2016 Chronology and Itinerary of the Career of J. Tim Brymn Materials for a Biography Peter M. Lefferts University of Nebraska-Lincoln This document is one in a series---"Chronology and Itinerary of the Career of"---devoted to a small number of African American musicians active ca. 1900-1950. They are fallout from my work on a pair of essays, "US Army Black Regimental Bands and The Appointments of Their First Black Bandmasters" (2013) and "Black US Army Bands and Their Bandmasters in World War I" (2012/2016). In all cases I have put into some kind of order a number of biographical research notes, principally drawing upon newspaper and genealogy databases. None of them is any kind of finished, polished document; all represent work in progress, complete with missing data and the occasional typographical error. -

Call Me Madam, P

NEW YORK CITY CENTER EDUCATION INSIDE ENCORES! Your personal guide to the performance. S AR E Y 5 7 TABLE OF CONTENTS CONTEXT Inspiration for Call Me Madam, p. 4-5 Meet the Creators & Artists, p. 6-7 An Interview with Casey Hushion, p. 8-9 Call Me Madam’s Lasting Influence on Encores!, p. 10-12 Glossary, p. 13 RESOURCES & ACTIVITIES Before the Show, p. 15 Intermission Activity, p. 16-17 After the Show, p. 18 Sources p. 19 Up Next for City Center Education p. 20-21 CONTEXT INSPIRATION FOR CALL ME Perle Mesta WHO WAS SHE? Perle Mesta was the first United States Ambassador to MADAM Luxembourg. The original “hostess with the mostest,” Mes- ta was known for hosting lavish parties in Washington D.C for almost 30 years. Born in Oklahoma, her family came into wealth when her father became involved in the oil and real-estate industries. In 1917 she married George Mesta, owner of Mesta Machinery. Mrs. Mesta became interested in politics when her husband introduced her to several high-ranking officials, including President Calvin Coolidge. Following her husband’s death, she became heavily involved in the quest for women’s rights and joined the National Women’s Party as its Congressional chairman and Public Relations specialist. While lobbying for the Equal Rights Amendment, she made a multitude of con- nections with politicians who would later attend her famous social gatherings. A Republican for most of her life, Mesta realigned herself with the Democratic party, opting to give financial support to then Senator Harry Truman. -

Vaudeville Trails Thru the West"

Thm^\Afest CHOGomTfca3M^si^'reirifii ai*r Maiiw«MawtiB»ci>»«w iwMX»ww» cr i:i wmmms misssm mm mm »ck»: m^ (sam m ^i^^^ This Book is the Property of PEi^MYOcm^M.AGE :m:^y:^r^''''< .y^''^..^-*Ky '''<. ^i^^m^^^ BONES, "Mr. Interlocutor, can you tell me why Herbert Lloyd's Guide Book is like a tooth brush?" INTERL. "No, Mr, Bones, why is Herbert Lloyd's Guide Book like a tooth brush?" BONES, "Because everybody should have one of their own". Give this entire book the "Once Over" and acquaint yourself with the great variety of information it contains. Verify all Train Times. Patronize the Advertisers, who I PLEASE have made this book possible. Be "Matey" and boost the book. This Guide is fully copyrighted and its rights will be protected. Two other Guide Books now being compiled, cover- ing the balance of the country. Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2012 with funding from Brigham Young University http://archive.org/details/vaudevilletrailsOOIIoy LIBRARY Brigham Young University AMERICANA PN 3 1197 23465 7887 — f Vauaeville Trails Thru tne ^iV^est *' By One vC^Jio Knows' M Copyrighted, 1919 by HERBERT LLOYD msiGimM wouNG<uNiveRSBtr UPb 1 HERBERT LLOYD'S VAUDEVILLE GUIDE GENERAL INDEX. Page Page Addresses 39 Muskogee 130-131 Advertiser's Index (follows this index) New Orleans 131 to 134 Advertising Rates... (On application) North Yakima 220 Calendar for 1919.... 30 Oakland ...135 to 137 Calendar for 1920 31 Ogden 138-139 Oklahoma City 140 to 142 CIRCUITS. Omaha 143 to 145 Ackerman Harris 19 & Portland 146 to 150 Interstate . -

Published Sheet Music from the Rudy Vallee Collection

Published Sheet Music from the Rudy Vallee Collection The Rudy Vallee collection contains almost 30.000 pieces of sheet music (about two thirds published and the rest manuscripts); about half of the titles are accessible through a database and we are presenting here the first ca. 2000 with full information. Song: 21 Guns for Susie (Boom! Boom! Boom!) Year: 1934 Composer: Myers, Richard Lyricist: Silverman, Al; Leslie, Bob; Leslie, Ken Arranger: Mason, Jack Song: 33rd Division March Year: 1928 Composer: Mader, Carl Song: About a Quarter to Nine From: Go into Your Dance (movie) Year: 1935 Composer: Warren, Harry Lyricist: Dubin, Al Arranger: Weirick, Paul Song: Ace of Clubs, The Year: 1926 Composer: Fiorito, Ted Arranger: Huffer, Fred Song: Ace of Diamonds, The Year: 1926 Composer: Fiorito, Ted Arranger: Huffer, Fred Song: Ace of Spades, The Year: 1926 Composer: Fiorito, Ted Arranger: Huffer, Fred K. Song: Actions (speak louder than words) Year: 1931 Composer: Vallee, Rudy; Himber, Richard; Greenblatt, Ben Lyricist: Vallee, Rudy; Himber, Richard; Greenblatt, Ben Arranger: Prince, Graham Song: Adios Year: 1931 Composer: Madriguera, Enric Lyricist: Woods, Eddie; Madriguera, Enric(Spanish translation) Arranger: Raph, Teddy Song: Adorable From: Adorable (movie) Year: 1933 Composer: Whiting, Richard A. Lyricist: Marion, George, Jr. Arranger: Mason, Jack; Rochette, J. (vocal trio) Song: African Lament (Lamento Africano) Year: 1931 Composer: Lecuona, Ernesto Lyricist: Gilbert, L. Wolfe Arranger: Katzman, Louis Song: African Lament (Lamento Africano) -

“To Be an American”: How Irving Berlin Assimilated Jewishness and Blackness in His Early Songs

“To Be an American”: How Irving Berlin Assimilated Jewishness and Blackness in his Early Songs A document submitted to The Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS in the Performance Studies Division of the College-Conservatory of Music 2011 by Kimberly Gelbwasser B.M., Northwestern University, 2004 M.M., University of Cincinnati, 2006 Committee Chair: Steven Cahn, Ph.D. Abstract During the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, millions of immigrants from Central and Eastern Europe as well as the Mediterranean countries arrived in the United States. New York City, in particular, became a hub where various nationalities coexisted and intermingled. Adding to the immigrant population were massive waves of former slaves migrating from the South. In this radically multicultural environment, Irving Berlin, a Jewish- Russian immigrant, became a songwriter. The cultural interaction that had the most profound effect upon Berlin’s early songwriting from 1907 to 1914 was that between his own Jewish population and the African-American population in New York City. In his early songs, Berlin highlights both Jewish and African- American stereotypical identities. Examining stereotypical ethnic markers in Berlin’s early songs reveals how he first revised and then traded his old Jewish identity for a new American identity as the “King of Ragtime.” This document presents two case studies that explore how Berlin not only incorporated stereotypical musical and textual markers of “blackness” within two of his individual Jewish novelty songs, but also converted them later to genres termed “coon” and “ragtime,” which were associated with African Americans. -

The Many Faces of “Dinah”: a Prewar American Popular Song and the Lineage of Its Recordings in the U.S

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE The Many Faces of “Dinah” The Many Faces of “Dinah”: A Prewar American Popular Song and the Lineage of its Recordings in the U.S. and Japan Edgar W. Pope 「ダイナ」の多面性 ──戦前アメリカと日本における一つの流行歌とそのレコード── エドガー・W・ポープ 要 約 1925年にニューヨークで作曲された「ダイナ」は、1920・30年代のアメリ カと日本両国におけるもっとも人気のあるポピュラーソングの一つになり、 数多くのアメリカ人と日本人の演奏家によって録音された。本稿では、1935 年までに両国で録音されたこの曲のレコードのなかで、最も人気があり流 行したもののいくつかを選択して分析し比較する。さらにアメリカの演奏家 たちによって生み出された「ダイナ」の演奏習慣を表示する。そして日本人 の演奏家たちが、自分たちの想像力を通してこの曲の新しい理解を重ねる中 で、レコードを通して日本に伝わった演奏習慣をどのように応用していった かを考察する。 1. Introduction “Dinah,” published in 1925, was one of the leading hit songs to emerge from New York City’s “Tin Pan Alley” music industry during the interwar period, and was recorded in the U.S. by numerous singers and dance bands during the late 1920s and 1930s. It was also one of the most popular songs of the 1930s in Japan, where Japanese composers, arrangers, lyricists and performers, inspired in part by U.S. records, developed and recorded their own versions. In this paper I examine and compare a selection of the American and Japanese recordings of this song with the aim of tracing lines ─ 155 ─ 愛知県立大学外国語学部紀要第43号(言語・文学編) of influence, focusing on the aural evidence of the recordings themselves in relation to their recording and release dates. The analysis will show how American recordings of the song, which resulted from complex interactions of African American and European American artists and musical styles, established certain loose conventions of performance practices that were conveyed to Japan and to Japanese artists. It will then show how these Japanese artists made flexible use of American precedents, while also drawing influences from other Japanese recordings and adding their own individual creative ideas. -

Florenz Ziegfeld Jr

CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, NORTHRIDGE ZIEGFELD GIRLS BEAUTY VERSUS TALENT A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Master of Arts in Theatre Arts By Cassandra Ristaino May 2012 The thesis of Cassandra Ristaino is approved: ______________________________________ __________________ Leigh Kennicott, Ph.D. Date ______________________________________ __________________ Christine A. Menzies, B.Ed., MFA Date ______________________________________ __________________ Ah-jeong Kim, Ph.D., Chair Date California State University, Northridge ii Dedication This thesis is dedicated to Jeremiah Ahern and my mother, Mary Hanlon for their endless support and encouragement. iii Acknowledgements First and foremost I would like to express my deepest gratitude to my thesis chair and graduate advisor Dr. Ah-Jeong Kim. Her patience, kindness, support and encouragement guided me to completing my degree and thesis with an improved understanding of who I am and what I can accomplish. This thesis would not have been possible without Professor Christine Menzies and Dr. Leigh Kennicott who guided me within the graduate program and served on my thesis committee with enthusiasm and care. Professor Menzies, I would like to thank for her genuine interest in my topic and her insight. Dr. Kennicott, I would like to thank for her expertise in my area of study and for her vigilant revisions. I am indebted to Oakwood Secondary School, particularly Dr. James Astman and Susan Schechtman. Without their support, encouragement and faith I would not have been able to accomplish this degree while maintaining and benefiting from my employment at Oakwood. I would like to thank my family for their continued support in all of my goals. -

ARSC Journal These Films

Sound Recording Reviews 213 Judy Garland: The Golden Years at M-G-M - The Harvey Girls, The Pirate, Summer Stock. MGMIUA Home Video. ML104869. 5 laser discs, 2 sides in CAV. 7 hours ofprerecordings on analog track; stereo in part; NTSC. Released in 1995. Thoroughbreds Don't Cry and Listen, Darling. MGMIUA Home Video. ML104569. 2 laser discs. 21 minutes ofprerecordings for Listen, Darling on analog track; NTSC. Released in 1994. The Ultimate Oz. MGM/UA Home Video and Turner. ML103990. Includes The Wizard of Oz, ML104755, 2 laser discs, 4 sides in CAV, THX and No-Noise; and The Wonderful Wizard of Oz: The Making of a Movie Classic, ML104756, 1 laser disc, THX. 4 hours 48 minutes of prerecordings on analog and digital tracks; NTSC. Released in 1993. The Wizard of Oz: Original Motion Picture Soundtrack. Rhino Movie Musicfl'urner Classic Movies R2 71964. 2 compact discs. Released in 1995. Meet Me In St. Louis: 50th Anniversary Edition. MGMIUA Home Video and Turner. ML104754. 3 laser discs and 1 compact disc of soundtrack (CD: MGM Records 305123). 4 sides in CAV; remixed from original multi-channel recording mas ters into stereo; 52 minutes of prerecordings on analog track; Includes The Making of an American Classic; NTSC. Released in 1994. CD also available separately on Rhino Movie Musicfl'urner Classic Movies R2 71958. Stereo. Released in 1995. Easter Parade: Original Motion Picture Soundtrack. Rhino Movie Musicfl'urner Classic Movies R2 71960. 1 compact disc. Released in 1995. That's Entertainment/ HI: Deluxe Collector's Edition. MGMIUA Home Video. ML103059. -

One Night with Fanny Brice

The American Century Theater presents Audience Guide Edited by Jack MarshallNovember 5–27 Rosslyn Spectrum Theater you can afford to seesee———— ppplaysplays you can’t afford to miss! About The American Century Theater The American Century Theater was founded in 1994. We are a professional company dedicated to presenting great, important, but overlooked American plays of the twentieth century . what Henry Luce called “the American Century.” The company’s mission is one of rediscovery, enlightenment, and perspective, not nostalgia or preservation. Americans must not lose the extraordinary vision and wisdom of past playwrights, nor can we afford to surrender our moorings to our shared cultural heritage. Our mission is also driven by a conviction that communities need theater, and theater needs audiences. To those ends, this company is committed to producing plays that challenge and move all Americans, of all ages, origins and points of view. In particular, we strive to create theatrical experiences that entire families can watch, enjoy, and discuss long afterward. These audience guides are part of our effort to enhance the appreciation of these works, so rich in history, content, and grist for debate. The American Century Theater is a 501(c)(3) professional nonprofit theater company dedicated to producing significant 20th Century American plays and musicals at risk of being forgotten. The American Century Theater is supported in part by Arlington County through the Cultural Affairs Division of the Department of Parks, Recreation, and Cultural Resources and the Arlington Commission for the Arts. This arts event is made possible in part by the Virginia Commission on the Arts and the National Endowment for the Arts, as well as by many generous donors.