Famine (IPC Phase 5) Risk Persists and Substantial Scale-Up of Assistance Needed

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

South Sudan Village Assessment Survey

IOM DISPLACEMENT TRACKING MATRIX VILLAGE ASSESSMENT SURVEY SOUTH SUD AN IOM DISPLACEMENT TRACKING MATRIX SOUTH SUDAN SOUTH SUDAN VILLAGE ASSESSMENT SURVEY DATA COLLECTION: August-November 2019 COUNTIES: Bor South, Rubkona, Wau THEMATIC AREAS: Shelter and Land Ownership, Access and Communications, Livelihoods, Markets, Food Security and Coping Strategies, Health, WASH, Education, Protection 1 IOM DISPLACEMENT TRACKING MATRIX VILLAGE ASSESSMENT SURVEY SOUTH SUD AN CONTENTS RUBKONA COUNTY OVERVIEW 15 DISPLACEMENT DYNAMICS 15 RETURN PATTERNS 15 PAYAM CONTEXTUAL INFORMATION 16 KEY FINDINGS 17 Shelter and Land Ownership 17 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 4 Access and Communications 17 LIST OF ACRONYMS 3 Markets, Food Security and Coping Strategies 17 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 4 Livelihoods 18 BACKROUND 6 Health 19 WASH 19 METHODOLOGY 6 Education 20 LIMITATIONS 7 Protection 20 WAU COUNTY OVERVIEW 8 BOR SOUTH COUNTY OVERVIEW 21 DISPLACEMENT DYNAMICS 8 RETURN PATTERNS 8 DISPLACEMENT DYNAMICS 21 PAYAM CONTEXTUAL INFORMATION 9 RETURN PATTERNS 21 KEY FINDINGS 10 PAYAM CONTEXTUAL INFORMATION 22 KEY FINDINGS 23 Shelter and Land Ownership 10 Access and Communications 10 Shelter and Land Ownership 23 Markets, Food Security and Coping Strategies 10 Access and Communications 23 Livelihoods 11 Markets, Food Security and Coping Strategies 23 Health 12 Livelihoods 24 WASH 13 Health 25 Protection 13 Education 26 Education 14 WASH 27 Protection 27 2 3 IOM DISPLACEMENT TRACKING MATRIX VILLAGE ASSESSMENT SURVEY SOUTH SUD AN LIST OF ACRONYMS AIDS: Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome -

Tables from the 5Th Sudan Population and Housing Census, 2008

Southern Sudan Counts: Tables from the 5th Sudan Population and Housing Census, 2008 November 19, 2010 CENSU OR S,S F TA RE T T IS N T E IC C S N A N A 123 D D β U E S V A N L R ∑σ µ U E A H T T I O U N O S S S C C S E Southern Sudan Counts: Tables from the 5th Sudan Population and Housing Census, 2008 November 19, 2010 ii Contents List of Tables ................................................................................................................. iv Acronyms ...................................................................................................................... x Foreword ....................................................................................................................... xiv Acknowledgements ........................................................................................................ xv Background and Mandate of the Southern Sudan Centre for Census, Statistics and Evaluation (SSCCSE) ...................................................................................................................... 1 Introduction ................................................................................................................... 1 History of Census-taking in Southern Sudan....................................................................... 2 Questionnaire Content, Sampling and Methodology ............................................................ 2 Implementation .............................................................................................................. 2 -

South Sudan: Jonglei – “We Have Always Been at War”

South Sudan: Jonglei – “We Have Always Been at War” Africa Report N°221 | 22 December 2014 International Crisis Group Headquarters Avenue Louise 149 1050 Brussels, Belgium Tel: +32 2 502 90 38 Fax: +32 2 502 50 38 [email protected] Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................... i I. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 II. Jonglei’s Conflicts Before the Civil War ........................................................................... 3 A. Perpetual Armed Rebellion ....................................................................................... 3 B. The Politics of Inter-Communal Conflict .................................................................. 4 1. The communal is political .................................................................................... 4 2. Mixed messages: Government response to intercommunal violence ................. 7 3. Ethnically-targeted civilian disarmament ........................................................... 8 C. Region over Ethnicity? Shifting Alliances between the Bahr el Ghazal Dinka, Greater Bor Dinka and Nuer ...................................................................................... 9 III. South Sudan’s Civil War in Jonglei .................................................................................. 12 A. Armed Factions in Jonglei ........................................................................................ -

Situation Overview: Jonglei State, South Sudan January-March 2018

Situation Overview: Jonglei State, South Sudan January-March 2018 Introduction Map 1: REACH assessment coverage Map 3: REACH assessment coverage Bor Town, c) two FGDs for Ayod in Bor PoC. of Jonglei State, January 2018 of Jonglei State, March 2018 All this information is included in the data used Ongoing conflict in Jonglei continued for this Situation Overview. to negatively affect humanitarian needs among the population in the first quarter of This Situation Overview provides an update 2018. Clashes between armed groups and to key findings from the November 2017 1 pervasive insecurity, particularly in northern Situation Overview. The first section analyses Jonglei caused displacement among affected displacement and population movement in communities, negatively impacting the ability Jonglei during the first quarter of 2018, and the to meet their primary needs. second section evaluates access to food and basic services for both IDP and non-displaced REACH has been assessing the situation in Map 2: REACH assessment coverage communities. hard-to-reach areas in South Sudan since of Jonglei State, February 2018 December 2015, to inform the response Population Movement and of humanitarian actors working outside of Displacement formal settlement sites. This settlement data Levels of depopulation remained high but is collected across South Sudan on a monthly stable overall in most parts of Jonglei in the first basis. Between 2 January and 23 March, Assessed settlements quarter of 2018. The proportion of assessed REACH interviewed 1527 Key Informants Settement settlements in Jonglei reporting that half or (KIs) with knowledge of humanitarian needs Cover percentae o aeed ettement reative to the OCHA COD tota dataet more of the population had left remained in 710 settlements in 7 of the 11 counties in similar between December 2017 (45%) and Jonglei State. -

SOUTH SUDAN Jonglei Reference Map

SOUTH SUDAN Jonglei reference map Pariang Mountain Nile Popuoch Berboi Wath Wang Tambuong Duoldong Waskedi Hotkech Kuerdop SUDAN Kwin Chok Manyajak Kanyang Kota Dugang Tharyier Kwirthar Kuerthok Bi Area B Dor Thworo Kuerlual Kuerkier Thukak Baliet Bei Deng Gak Fatugu Wuobo Fatwuk Patit Ful Nyak Nahr Sobat Gar Bulriah Diel Fakur Mandeng Nyinakoon Wut Akot Wilnyang Wulaokot Fakwam Yaradew Adidiang Kuir Kwol Keuern Kolanyang Deng Luat Againg Kotyaka Ayoolyool Badodi Malwal Khorfulus Tharliel Chielbiluang Ngautoch Mudi Fekang Kuernyiene Mundeing Wang Yag Wutkot Kwan Bwing Shebalueng Agak Gobjak Kuerdew Adiang Toi Keew Theke Ful Lual Ngenyakol Wunalong Mareng Fatach Kuernyang Wuthol Pulita Buol Nurlonga Koldhuor Amanyang Wunkuach Fagh Atar Wunbiar Wunakir Kontet Panyang 2 Kuerkuon Bwon Ngera Korwai Abendel Panyikang Torniok Majoknyang Machar Patai Nyokkuach Shol Ajok Katjur Patuel (1) Longochuk ETHIOPIA Guit Dortwoi Yom Retchol Dhuony Abwong Dulareng Pagune Wangthiel Patuel (2) Nur Koleng Jungyang Thanilak Gamtang Wang Kiel Angnor Fachod Tike Gmatong Wunapith Kuolachuor Maling Paguer Neinjang Chweg But Chotkol Kuolakou Awoulgok Abon Wunanyak Jat Metal Kuer Kulang Choatbora CENTRAL Kachnhial Pieth Wunalam Chuei Puyai Mulekich Wutdeng AFRICAN Kot Kayoh Fwor Bieu Canal/pigi Fangak Riep Fangak Lam Shwai REPUBLIC Lil Fuyach Doregh Kieriel Fajur Dhoareak Fulfam Payat Putuni Wan Kaljak Reng Agayng Kwendil Mayen Pajok Pulieth Paguen Dier Kan Fayat Ngong Wunlam Wunlam Longtam Wunadong Ruv-dub Toch Wundong Loungteam Manadwai Wunakei Fasay Diera Buk -

EVALUATION Mid-Term Evaluation of the Integrated Disease Surveillance and Response Project

EVALUATION Mid-Term Evaluation of the Integrated Disease Surveillance and Response Project December 14, 2011 This publication was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development. It was prepared by Bob Pond, Hammam El Sakka, Joseph Wamala and Luswa Lukwago, Management Systems International. MID-TERM EVALUATION OF THE INTEGRATED DISEASE SURVEILLANCE AND RESPONSE PROJECT DECEMBER 14, 2011 This publication was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development. It was prepared by Bob Pond, Hammam El Sakka, Joseph Wamala and Luswa Lukwago, Management Systems International. MID-TERM EVALUATION OF THE INTEGRATED DISEASE SURVEILLANCE AND RESPONSE PROJECT Contracted No. DFD-1-00-05-00251-00, Task Order No. 2 Services under Program and Project Offices for Results Tracking (SUPPORT) DISCLAIMER The author’s views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government. CONTENTS List of Tables ............................................................................................................................. ii List of Figures ........................................................................................................................... ii Acknowledgements .................................................................................................................. iii Executive Summary.................................................................................................................. -

Sudan Rural Land Governance (Srlg) Project

SUDAN RURAL LAND GOVERNANCE (SRLG) PROJECT LAND CONFLICTS LEGAL BRIEF JULY 2013 This publication was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development. It was prepared by Tetra Tech ARD. Prepared for United States Agency for International Development, USAID Contract Number EDH-I-00- 05-00006, Task Order12, Sudan Rural Land Governance Project under the RAISE Plus Indefinite Quantity Contract (IQC) Tetra Tech ARD Principal Contacts: Marc Dawson Chief of Party Tetra Tech ARD Juba, South Sudan Tel: 095 640 3592 [email protected] Sandy Stark Project Manager Tetra Tech ARD Burlington, Vermont Tel.: 802-658-3890 [email protected] Megan Huth Senior Technical Advisor/Manager Tetra Tech ARD Burlington, Vermont Tel.: 802-658-3890 [email protected] SUDAN RURAL LAND GOVERNANCE (SRLG) PROJECT LAND CONFLICTS LEGAL BRIEF JULY 2013 DISCLAIMER The authors' views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government. CONTENTS CONTENTS ................................................................................................................................... I ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS ....................................................................................... II EXECUTIVE SUMMARY.............................................................................................................. 1 1.0 OVERVIEW OF LAND BASED CONFLICTS ................................................................... -

585A58164.Pdf

! (as of Dec 2016) ! ! ! ! Jonglei St!ate Map ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 30°E 31°E 32°E ! !33°E ! 34°E 35°E ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Managla !!Thon ! Merial ! Es Safur Faduth Fadit Wutau Panenul Beneshowa ! Um!m Biera Biu ! Ogod ! Ryagdo! ! ! ! ! El Araish ! R ! Yar Rungun ! Atietit . ! Tareng ! Agat A Abmju ! Achop ! ! ! Abmju Bango ! Guel Guk da Tiang Diar El Harr! ! ! W Malakal r Son!ca Boac ! Mirich hit Fafuojo Panyikang ! ! Legends: Pariang ! ! e Nil ! ! Kajbai 2 Machar Marshes ! e ! ! Wor Char ! ! Tonga ! ! ! Dute ! ! ! " ! Maban Liette Buheyrat No ! Adodo! Bum Buo!thgark B!arboi ! ! ! ! ! Ninding ! Alel Upper Nile ! Settlements ! Maya Doleib ! New Fangak Panid!w!ay ! Nyilwak Narir Pul Luthn!i " ! ! Kajibai 1/Wu ! Owup ! Ju!a!ibor ! ! ! ! Wunyok ! " ! ! ! Biil ! ! ! Doleib Nagdiar ! ! ! ! ! ! R Agok Chotbora Nyilwa!k ! . S ! ! ! ! Ngwer Kuernyang Fa!chop ! ! ! o State Capitals ! Jok!wot ! Pakoi Fan!!ie ! ! ba Udier Rub-Koni Nimni ! ! Pakang! ! ! ! t Baliet ! ! Nimnim Kaikang " ! ! ! ! ! ! Jogiel ! Rom ! ! ! Baliet ! Gutur ! A!u!'u ! ! Kau! Ngautoch Abu Jop " ! ! " " Nyin Yar Keew Atar ! Atar R ! ! " Wijur Ditchin ! . D ! ! ! Wun-Gak Ajak Kuoc ! ! ag Larger Towns ! ! ! Yoynyang Atar 2 ! ! ! a Rubkona Jwol Chuei Gok Machar ! ! ! ! Fangak Kir ! " Chotbora ! ! ! Chotbora "! ! ! ! ! Kuo ! ! Longochuk ! ! ! Yom ! Thantok Abwong Atar 2 ! ! Lu!ale ! ! ! Tarom Yiikou " !Tig!e ! ! Akoc ! ! !Thangoro Guit Chuth Akol ! ! ! !! ! Mayen Abun ! Rubmyheai Ru!bnyagai ! Wang Kiel Abon ! Dajo Towns ! ! ! ! Paderna ! Gwit Rupiana ! ! ! Kwenek -

The Impact of Urbanization on the Livelihood of Bor Community in Bor

THE IMPACT OF URBANIZATION ON THE LIVELIHOOD OF BOR COMMUNITY IN BOR COUNTY OF JONGLEI STATE, SOUTH SUDAN BY CHOL DANIEL DENG GARANG C50/81809/2015 A PROJECT PAPER SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENT FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN URBAN GEOGRAPHY IN THE DEPARTMENT OF GEOGRAPHY AND ENVIRONMENTAL STUDIES, UNIVERSITY OF NAIROBI NOVEMBER 2017 DECLARATION This Project Paper is my original work and has not been presented for award of degree in any other University Chol Daniel Deng Garang C50/81809/2015 This Project Paper has been submitted with our approval as University Supervisors Dr. Samuel Owuor Department of Geography and Environmental Studies University of Nairobi Dr. Jacqueline Walubwa Department of Geography and Environmental Studies University of Nairobi ii DEDICATION I dedicate this work to my beloved Father, late Deng Garang Aleer and Mother, Nyandeng Garang Atem, and my brothers, who have supported me to complete this study successfully. To them I am very grateful. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My deepest gratitude goes to the Almighty God for giving me the strength and life to pursue my studies to completion. I wish to acknowledge my profound gratitude to my supervisors, Dr. Samuel Owuor and Dr. Jacqueline Walubwa for their valuable guidance offered during the various stages of this study. Their wise counsel, encouragement and patience made it possible for the study to come to completion within a reasonable duration. My great appreciation and indebtedness also goes to the Bor community elders, Dr. John Garang Memorial University of Science and Technology, Rumbek University of Science and Technology, Oxfam GB in Jonglei State, Dr. -

South Sudan: - Ebola Visur Disease (EVD) Risk Map, 2018 South Sudan

South Sudan: - Ebola Visur Disease (EVD) Risk Map, 2018 South Sudan Khorgana Catom Garbek Yup Yian Weijiokni Old Akobo Manyiel Manyiel Catom Nyal KHOR NGOLIMBO Kanyuhial Bongjok Pajut Abul KHOR Tonj Wun-kot Nyadong Nyawiet Ayod Kuru GANA Ngolembo Acieek Tiam Dorok Derkuach Yabulu GANA o Mayen-Loc Maper Centre Youp Derkuach Mer Kuru v® Wau Acieek Wuding Nyawiet Mer " Kak Amiel Amiel Pagaleng Map date: 10 SEeptthemiboerp 2i0a18 Wau North Tonj Pakam Wunthor Burmath Ngisa Kuajena Wun-Rieng Mareang Momoi Bussere Padida Chiban Gette Jeliw Bussere East Madhool Amook CHIRAANMAAR Jolong Bagari Taban Madhool Pabuong Duk Patuatnoi Wadh-alal Kuajena Bussere Mayen Pawai Pawai Payuel NGODAKALA Bussere Mayen Akobo Warrap Mayen Poktap Jolong Raga Taban Mayen Panyijiar NGODAKALA Wathalel/Wadlelo Tiap Wundhiot Wundhiot Chuk KABEK Uror Monychak Mbili Pariel Monychak Nyergany Taban Mbili Wundhiot MABIOR Kuerjena Malou Cueibet Mabil KAWER Western Wathalel/Wadlelo Wundhiot Makur Kongor Malou Akot PABARCIKOK MABIOR Nyergany Gittan Anaak Parun Dangachak Delai Nyergany Bahr El Dangachak Ram-ateer Akot Kiir MALEI Kongor Wau Dangachak Anaak Kongor Tontol Pochalla Wathalel/Wadlelo Maper Kiir Kongor Tontol Ghazal Maju Malou Anaak Delai Kongor Dangachak Alur Anaak Garatei WANGULEI Tontol Otalo Malou Tontol Alieo Kpaile Dangachak Malou Dak Ayen Twic Garatei Tontol Two Panyijiar Tontol Otalo Two Ojwa Alur Alur Shambe Port Kpaile Alur Tonj Malou Yardong Malou CUEICOK Shambe BAPING Tontol Alur Magotic East Kuachthor Kongor Talo Nakpatagum WUNTHOU WUTKORO Monychak Dalmany -

Diminishing Powers of Traditional Leaders: the Case for Dinka Bor Social Revival

Walden University ScholarWorks Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies Collection 2020 Diminishing Powers of Traditional Leaders: The Case for Dinka Bor Social Revival Daniel Leek Geu Walden University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.waldenu.edu/dissertations Part of the African Languages and Societies Commons, and the Philosophy of Science Commons This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies Collection at ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Walden University College of Social and Behavioral Sciences This is to certify that the doctoral dissertation by Daniel Leek Geu has been found to be complete and satisfactory in all respects, and that any and all revisions required by the review committee have been made. Review Committee Dr. Gerald Regier, Committee Chairperson, Public Policy and Administration Faculty Dr. Chizoba Madueke, Committee Member, Public Policy and Administration Faculty Dr. George Kieh, University Reviewer, Public Policy and Administration Faculty Chief Academic Officer and Provost Sue Subocz, Ph.D. Walden University 2020 Abstract Diminishing Powers of Traditional Leaders: The Case for Dinka Bor Social Revival by Daniel Leek Geu MA, American Military University, 2012 BS, North Dakota State University, 2008 Dissertation Submitted in Partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Public Policy and Administration Walden University August 2020 Abstract The impact of diminishing powers of Dinka Bor traditional leaders is affecting how the community is recovering from the protracted civil war in South Sudan. -

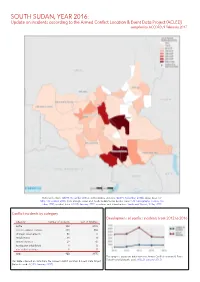

SOUTH SUDAN, YEAR 2016: Update on Incidents According to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) Compiled by ACCORD, 9 February 2017

SOUTH SUDAN, YEAR 2016: Update on incidents according to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) compiled by ACCORD, 9 February 2017 National borders: GADM, November 2015a; administrative divisions: GADM, November 2015b; Abyei Area: SS- NBS, 1 December 2008; Ilemi triangle status and South Sudan/Sudan border status: UN Cartographic Section, Oc- tober 2011; incident data: ACLED, January 2017; coastlines and inland waters: Smith and Wessel, 1 May 2015 Conflict incidents by category Development of conflict incidents from 2012 to 2016 category number of incidents sum of fatalities battle 390 2438 violence against civilians 338 884 strategic developments 80 0 riots/protests 61 8 remote violence 29 45 headquater established 1 0 non-violent activities 1 0 total 900 3375 This graph is based on data from the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (datasets used: ACLED, January 2017). This table is based on data from the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (datasets used: ACLED, January 2017). SOUTH SUDAN, YEAR 2016: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 9 FEBRUARY 2017 LOCALIZATION OF CONFLICT INCIDENTS Note: The following list is an overview of the incident data included in the ACLED dataset. More details are available in the actual dataset (date, location data, event type, involved actors, information sources, etc.). In the following list, the names of event locations are taken from ACLED, while the administrative region names are taken from GADM data which serves as the basis for the map above. Data on incidents in the Abyei area are not reflected in this update.