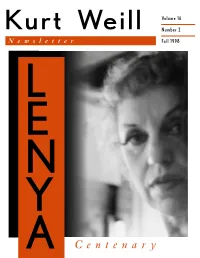

A Centenary Volume 16 in This Issue Kurt Weill Number 2 Newsletter Fall 1998 Lenya Centenary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

News and Events

Volume 16 Number 1 topical Weill Spring 1998 A supplement to the Kurt Weill Newsletter news &news events news &news events Lotte Lenya Centenary Update Pictorial autobiography in press Weill-Lenya radio play on BBC Lenya, the Legend: A Pictorial Autobiog- radio 4 raphy will be published in August by The On 1 June 1998, BBC Radio 4 will broad- Overlook Press in the U.S. and by Thames cast the premiere of a new radio play, The Hudson in the U.K. In the book, more Trouble You Bring Me: Scenes from the than 300 photographs are accompanied by Marriage of Kurt Weill and Lotte Lenya. a narrative comprised of Lenya’s own Adapted by Tony Staveacre from memoirs words taken from her interviews, letters, and the recently published correspon- and other writings. Lenya’s voice brings dence, the play features a narrator these captivating glimpses into her (Staveacre) and the voices of Weill and world—on stage and off—to life in the Lenya as portrayed by Henry Goodman witty, caustic, and insightful manner that and Kelly Hunter. Goodman is currently is hers alone. appearing in the West End in Chicago. Compiled and edited by David Hunter, who won last year’s Sony Award Farneth, Director of the Weill-Lenya for Best Dramatic Performance on British Research Center, the book spans Lenya’s Radio, is now playing with the Royal six-decade career, covering her stage and Shakespeare Company. The 45-minute movie roles, recording sessions, concert broadcast will be repeated 18 October 1998 appearances, and awards. Also included at 2:15 P.M., on Lenya’s 100th birthday. -

Marianne Oswald Et La Critique Musicale : La Construction Du Personnage Artistique Depuis Ses Multiples Perspectives

!"#$#%&'#(#)&*+&,,"#-'.&/0#"1#/&#%*+1+23"#43'+%&/"#5## !&#%6,'1*3%1+6,#03#7"*'6,,&8"#&*1+'1+23"#0"73+'#'"'#43/1+7/"'#7"*'7"%1+9"'# ! ! ! ! ! ! "#$%&'(!)(**'(+! ! ! ! ! ! ! ),-*(!.%/0*%(!1!234502(!.(*!%6#.(*!*#/%+'(#+(*!(6!/0*6.0560+72(*!(&!8#(!.(!23096(&6'0&!.(! 27!:7;6+'*(!-*!<+6*!(&!=#*'>#(!78(5!*/%5'72'*76'0&!(&!%6#.(*!.(*!?(==(*! ! ! ! ! @'+(56(#+!A!B+0?(**(#+!C,+'*60/,(+!:00+(! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! D&'8(+*'6%!.3E667F7!G!D&'8(+*'6H!0?!E667F7! I#'22(6!JKLM! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! N!"#$%&'(!)(**'(+O!E667F7O!C7&7.7O!JKLM# # :;<=);! P0&.%(!*#+!237//+05,(!/+0/0*%(!/7+!B,'2'/!<#*27&.(+!QJKKRSO!5(66(!6,-*(!(*6!5(&6+%(! *#+!27!50&*6+#56'0&!.#!/(+*0&&7$(!7+6'*6'>#(!.(!27!5,7&6(#*(!?+7&T7'*(!:7+'7&&(!E*F72.! QLMKLULMVWSO! 27! +(276'0&! .'720$'>#(! >#3(22(! (&6+(6'(&6! 78(5! *(*! /#92'5*! (6! *7! /+%*(&5(! 1! 6+78(+*!27!=%=0'+(!(6!23,'*60'+(!5#26#+(22(X!<#Y0#+.3,#'!=%50&&#*O!*0&!&0&U50&?0+='*=(O! *0&! *6H2(! 80572! /7+2%U5,7&6%O! *7! &76#+(! (&$7$%(! (6! *7! ?0+5(! /027+'*7&6(! '&*/'+(&6! #&(! '=/0+67&6(!%2'6(!7+6'*6'>#(!1!B7+'*!(6!2#'!872(&6!2(!6'6+(!.37+6'*6(!27!/2#*!.'*5#6%(!.(*!7&&%(*! LMZK!.7&*!27!/+(**(X![!6+78(+*!2(*!50&5(/6*!.37#6,(&6'5'6%!(6!.(!?%='&'6%*O!6(2*!>#(!+(2(8%*! .7&*!27!/+(**(!7+6'*6'>#(O!237#609'0$+7/,'(!.(!27!5,7&6(#*(!(6!*0&!+%/(+60'+(!=#*'572O!5(66(! +(5,(+5,(! (\/20+(! 23'&5'.(&5(! .(*! +7//0+6*! .(! +%5'/+05'6%! >#'! *3(\(+5(&6! (&6+(! 2(! /(+*0&&7$(O!2(!/#92'5!(6!27!=%=0'+(!*#+!27!+%5(/6'0&!(6!27!5+%76'0&!.3#&(!=#26'/2'5'6%!.(! +(/+%*(&676'0&*!.#!/(+*0&&7$(!7+6'*6'>#(!(6!*#$$-+(!>#(!:7+'7&&(!E*F72.!7!6(&#!#&!+]2(! 6+7&*?0+=76'0&&(2!.7&*!23,'*60'+(!=#*'572(!(6!5#26#+(22(!?+7&T7'*(X! -

Francis Poulenc Dalai

CSEREKLYEI ANDREA FRANCIS POULENC DALAI DOKTORI ÉRTEKEZÉS 2017 Liszt Ferenc Zeneművészeti Egyetem 28-as számú művészet- és művelődéstörténeti besorolású doktori iskola FRANCIS POULENC DALAI Louise de Vilmorin dalciklusok CSEREKLYEI ANDREA DOKTORI ÉRTEKEZÉS 2017 I Tartalomjegyzék Rövidítések II Köszönetnyilvánítás III Bevezetés IV 1. A dalokról 1 1.1. Hatások 1 1.2. A húszas évek 7 1.3. A harmincas évek eleje 9 1.4. Pierre Bernac 15 1.5. Fordulat 16 1.6. Háborús évek 18 1.7. A háború utáni évek 25 1.8. Az utolsó évtized 29 2. Kompozíciós technikák Poulenc dalaiban 36 2.1. Szövegválasztás, fordítások 36 2.2. Zongorakíséret, hangszerelés 38 2.3. Forma, szerkezet, dallam, harmónia 40 3. Louise de Vilmorin 44 4. Trois poèmes de Louise de Vilmorin (FP 91) 51 5. Fiançailles pour rire (FP 101) 63 6. Métamorphoses (FP 121) 85 7. Záró gondolatok 93 8. Függelék – A dalok jegyzéke 94 9. Bibliográfia 101 II Rövidítések André de Vilmorin André de Vilmorin: Essai sur Louise de Vilmorin. (Paris: Édition Pierre Seghers, 1962.) Audel 1978 Stéphane Audel: My friends and Myself. [Moi et mes amis.] Ford: James Harding. (London: Dennis Dobson, 1978.) Bernac 1977 Pierre Bernac: Francis Poulenc. The Man and His Songs. [Francis Poulenc et ses mélodies]. Ford: Winifred Radford. (London: Victor Gollancz, 1977.) Correspondance 1967 Francis Poulenc: Correspondance 1915-1963. (Paris: Éditions du Seuil, 1967.) Daniel 1982 Keith W. Daniel: Francis Poulenc. His Artistic Development and Musical Style. (Ann Arbor, Michigan: UMI Research Press, 1982.) Gyergyai Gyergyai Albert: „A szép kertésznő”. Kritika 17/4 (1979. ápr.) 19-21. Henri Hell 1958 Henri Hell: Francis Poulenc. -

Francis Poulenc Et La Musique Populaire

UNIVERSITÉ PARIS-SORBONNE ECOLE DOCTORALE V (ED 0433) CONCEPTS ET LANGAGES EA 206 Observatoire Musical Français (OMF) T H È S E pour obtenir le grade de DOCTEUR DE L’UNIVERSITÉ PARIS-SORBONNE Discipline : Musique et Musicologie Présentée et soutenue par Dominique ARBEY le 14 octobre 2011 Francis Poulenc et la musique populaire sous la direction de Madame le Professeur Danièle PISTONE MEMBRES du JURY Monsieur Christian CORRE Professeur à l’Université Paris 8, président du jury Monsieur Luc CHARLES-DOMINIQUE Professeur à l’Université de Nice Monsieur François MADURELL Professeur à l’Université Paris-Sorbonne Madame Danièle PISTONE Professeur à l’Université Paris-Sorbonne 1 Remerciements Je souhaite exprimer mes remerciements à Mme Danièle Pistone, ma directrice de thèse pour ses conseils précieux, sa disponibilité et la qualité des échanges que nous avons eus. Son professionnalisme et son expérience ont été un soutien appréciable dans l’organisation de mon travail de recherche. Je remercie également MM. Christian Corre, Luc Charles-Dominique et François Madurell d’avoir accepté d’être membres du jury. AVERTISSEMENT : dans cette version en ligne de ma thèse, les illustrations sont cachées afin de respecter les dispositions du code de la propriété intellectuelle. 2 Introduction Cette thèse a pour objet l’étude d’un aspect important du langage musical de Francis Poulenc (1899-1963) : la présence d’idiomes populaires dans son écriture. Cette particularité confère à son œuvre une « couleur » et un style immédiatement reconnaissables : de nombreux emprunts à la chanson et au music-hall du début du XXe siècle jalonnent celle-ci. L’étude de cette caractéristique permettra de définir le style du compositeur, sujet jugé « tabou » par ce dernier. -

Le Tremplin Des Cabarets

1934 1945 1972 George Chepfer a été l’un des Dès la fin de la guerre, les Parmi les salles de concert les artistes les plus courrus de bals populaires sont le rendez- plus connues figure le Caveau Paris. Il a enregistré son pre- vous de tous ceux qui veulent des Trinitaires dont les véri- mier disque à la soixantaine et se dégourdir les gambettes au tables débuts ont eu lieu en obtenu un Grand prix en 1934. son des orchestres. 1972. La consécration pour Chepfer La vogue des bals populaires Le début des Trinitaires numéro 11 100 ANS DE MÉMOIRE On connaît SPECTACLES VEDETTES Tous les grands artistes de la chanson sont venus se produire à Metz la chanson La chanson française a plus de mille ans d’histoire. Elle allie ainsi tout naturellement une évidente continuité à une prolifération des formes, des styles et du langage qui n’a fait que croître au rythme de la succession des époques. Depuis le début de ce siècle, le mouvement a été En haut de l’affiche s’accélérant suivant en cela la métamorphose perpétuelle des modes, des idées et des courants esthétiques. Après la Seconde Guerre mondiale, il est devenu quasiment frénétique comme la vie même. La société de surproduction et de surconsommation, les pressions exercées par les idéologies, les courants régionalistes, écologistes, féministes et surtout par les médias (radio, télévision principalement), tout a contribué à la fugacité, à la précarité, aux mélanges des genres qui sont quelques-uns des traits les plus frappants de la chanson actuelle. Dans le même temps s’est ouvert un fossé de plus en plus large entre les authentiques créateurs et les fabricants et techniciens de l’industrie phonographique. -

Catalogue of Compositions

CATALOGUE OF COMPOSITIONS COMPILED BY MADELEINE MILHAUD FROM THE COMPOSER'S NOTEBOOKS AND REVISED BY JANE HOHFELD GALANTE The translator owes a debt of gratitude to Mme. Milhaud for the many hours of assistance, helpful counsel, and gracious hospitality she contributed to the revision of this catalogue. Very special appreciation is also due toR. Wood Massi for his extensive work in verifying and re-ordering data pertaining to the music, to Jean-Franfois Denis for his excellently detailed preparation of the final copy, and to Dr. Katharine M. Warne for her constructive perusal of the proofs and her many invaluable suggestions. I should like to thank the Mills College Department ofMusic for providing research funds and the Mills College Library for giving me unlimited access to the Milhaud collection. I am especially grateful to Eva Konrad Kreshka for her unstinting encouragement and enthusiasm. The careful reader will note some discrepancies between this catalogue, which is based on Milhaud's notebooks, and the printed scores, mostly in regard to exact dates, places ofcomposition, and timing. In the majority of instances, the notebook entry is the one used except where information given on the score adds something ofspecial interest. !.H. G. CATALOGUE OF COMPOSITIONS ARRANGED CHRONOLOGICALLY BY CATEGORIES Entry format ____________________ Title opus number (Recording available) (general comments) [Text author] Section titles Cross references Place, date (day, month, year) of composition Orchestration Publisher: (former publisher) present publisher Dedication and/or commission First performance: Date (day, month, year). Place. Artist Duration: min s 231 Explanation of terms ___________________ The designation (R) means that the work has been recorded. -

Marianne Oswald

Oswald, Marianne Marianne Oswald Geboren in Saargemünd (heute Sarreguemines), einem Geburtsname: Sarah Alice Bloch kleinen Ort in Lothringen, wuchs Marianne Oswald ge- Ehename: Marianne Sarah Alice Colin wissermaßen zwischen Deutschland und Frankreich auf. Varianten: Marianne Bloch, Marianne Colin, Marianne Ihre Chansonkarriere begann sie im Berlin der 1920er Bloch-Colin, Marianne Sarah Alice Oswald, Marianne Jahre, aber ihr Bezugs- und Sehnsuchtspunkt war seit Sarah Alice Bloch, Marianne Sarah Alice Bloch-Colin frühester Kindheit Paris. Dort machte sie in den 1930er Jahren eine blitzartige Karriere als Chansonsängerin auf * 9. Januar 1901 in Saargemünd (heute Kabarett- und Music-Hall-Bühnen. Tourneen innerhalb Sarreguemines), Frankreichs, in die Schweiz und Belgien folgten. Kurz † 25. Februar 1985 in Limeil-Brévannes, vor Kriegsausbruch wurde sie an ein französisches Kaba- rett in New York engagiert. 1947 kehrte sie nach Frank- Chansonsängerin, Schauspielerin, Schriftstellerin, reich zurück, das, wenn sie auch gelegentlich in Deutsch- Drehbuchautorin, Produzentin land auftrat, ihr Hauptwirkungsland blieb. Biografie „C'est pour ceux-là qu'elle chante et si sa voix ne ressemble à aucune autre c'est parce qu'el- „Mit einem Fuß in Frankreich, mit dem anderen in Deut- le est à peine sa voix mais bien plutôt la voix de milliers schland“ d'autres qui ne chantent pas, qui ne chantent plus ou qui n'ont jamais osé chanter“ Marianne Oswald wurde als Alice Bloch am 9. Januar 1901 in eine wohlhabende jüdische Familie im damals („Die sind es, für die sie singt deutschen Städtchen Saargemünd (heute Sarreguemi- und wenn ihre Stimme keiner anderen gleicht liegt das nes) in Lothringen, direkt an der Grenze zum Saarland, daran, dass es kaum ihre Stimme ist, sondern viel eher geboren. -

Marianne OSWALD, Vers Une (Im)Possible Reconnaissance

4m ECOLE NATIONALE UNIVERSITE DES SCIENCES SUPERIEURE DES SCIENCES SOCIALES GRENOBLE II DE L'INFORMATION ET DES BIBLIOTHEQUES INSTITUT D'ETUDES POLITIQUES Diplome Sup6rieur D.E.S.S. Direction de de BibliotMcaire (D.S.B) projets culturels Projet de recherche Marianne OSWALD, vers une (im)possible reconnaissance " fe N S Michel BOLCHERT sous la direction de C£cile MEADEL Centre de sociologie de 1'innovation, Paris fti 1992 Marianne OSWALD, vers une (im)possible reconnaissance RESUME : Comment une personnalitd, comme celle de Marianne OSWALD (1901-1985) chanteuse, actrice, productrice d'emissions radiophoniques et te!6visis6es, peut-elle devenir l'enjeu d'une politique culturelle locale? L'auteur tente de definir un projet dans un contexte politique et culturel defxni (Sarreguemines, 23 OOOh.) DESCRIPTEURS : OSWALD (Marianne) POLITIQUE CULTURELLE, definition fflSTOIRE CULTURELLE, France, 1931-1970 Marianne OSWALD with an aim to (im)possible recognition ABSTRACT : How a personality, such as that of Marianne OSWALD (1901-1985), singer, actress, producer of radio and television shows, becomes the battleground in local cultural politics ? The autor is attempting to define a project in a particular political and cultural context. KEYWORDS : OSWALD (Marianne) LOCAL CULTURAL POLITICS, definition CULTURE HISTORY, France, 1931-1970 SOMMAIRE Marianne OSWALD, portrait p. 1 Problcmatique 1. Marianne OSWALD, celebre et oubliee p. 3 2. Marianne OSWALD, un enjeu culturel p. 5 3. Marianne OSWALD, quel projet ? p. 7 Les instruments de la recherche 1. Les entretiens 1.1. Methodologie p. 10 1.2. Quels cercles d'interlocution? p.10 1.3. Choix d'entretiens * Janine MARC-PEZET, pr6sidente de la Societ6 des Amis de p.11 Mariaime OSWALD * Helene HAZERA, critique musicale p.17 * Robert PAX, maire de la ville de Sarreguemines p.23 * Jean SEITLINGER, depute et parlemcntaire europeen p.28 * Jean CAHN, adjoint au maire de la ville de Sarreguemines delegue aux affaires culturelles p.33 2. -

Jean Cocteau and Georges Auric

Jean Cocteau and Georges Auric: The Poésie and Music That Shaped Their Collaboration in the Mélodies, Huit poèmes de Jean Cocteau (1918) Deborah A Moss BMus (Hons) MMus A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) Kingston University March 2021 Abstract Jean Cocteau and Georges Auric: The Poésie and Music That Shaped Their Collaboration in the Mélodies, Huit poèmes de Jean Cocteau (1918) Georges Auric (1899–1983) was the preferred musician of the author, impresario, cinematograph and artistic innovator Jean Cocteau (1889–1963). This was borne out by their fifty-year friendship and working relationship. Auric composed the soundtracks for all of Cocteau’s films. Their long-term alliance was based on mutual admiration and a shared transdisciplinary artistic aesthetic, motivated at the start by a desire to initiate a post-First World War new French musical identity. The collaboration did not fulfil the generally accepted understanding of the term, that of working simultaneously and in close proximity. Their creative processes were most successful when they worked individually and exchanged ideas from a distance through published correspondence and articles. Jean Cocteau’s creative practice spanned all of his artistic disciplines except music. Indeed, he chose not to be restricted by the limitations of any particular art form. Yet, he had a strong musical affinity and music was integral to the shaping of his diverse productions. He longed to be a musician and relied on Georges Auric to fill the musical void in his artistic practice. This thesis explores two mélodies, Hommage à Erik Satie and Portrait d’Henri Rousseau, the first and last, in Auric’s song series Huit poèmes de Jean Cocteau (1918)—one of his early collaborations with Cocteau. -

A Centenary Volume 16 in This Issue Kurt Weill Number 2 Newsletter Fall 1998 Lenya Centenary

Volume 16 Kurt Weill Number 2 Newsletter Fall 1998 L E N Y A Centenary Volume 16 In this issue Kurt Weill Number 2 Newsletter Fall 1998 Lenya Centenary In Praise of a Career 3 I Remember Lenya 4 ISSN 0899-6407 Listening to Lenya 8 David Hamilton © 1998 Kurt Weill Foundation for Music 7 East 20th Street Books New York, NY 10003-1106 tel. (212) 505-5240 Excerpts from fax (212) 353-9663 Lenya the Legend edited by David Farneth 13 Emigrierte Komponisten in der Medienlandschaft The Newsletter is published to provide an open forum des Exils 1933-1945 edited by Nils Grosch, wherein interested readers may express a variety of opin- Joachim Lucchesi, and Jürgen Schebera 14 ions. The opinions expressed do not necessarily represent Wolfgang Jacobsen the publisher’s official viewpoint. The editor encourages the submission of articles, reviews, and news items for inclusion Kurt Weill work entries in in future issues. Pipers Enzyklopädie des Musiktheaters 15 Nils Grosch Performances Staff David Farneth, Editor Lys Symonette, Translator Propheten in London 16 Andrew Porter Edward Harsh, Associate Editor Dave Stein, Production Joanna Lee, Associate Editor Brian Butcher, Production Mahagonny in Salzburg 18 Rodney Milnes Kurt Weill Foundation Trustees “Go for Kurt Weill” in Salzburg 19 Kim Kowalke, President Paul Epstein Nils Grosch Lys Symonette, Vice-President Walter Hinderer Mahagonny Songspiel in Karlsruhe 20 Philip Getter, Vice-President Harold Prince Andreas Hauff Guy Stern, Secretary Julius Rudel Recordings Milton Coleman, Treasurer Symphony no. -

Marianne OSWALD, Vers Une (Im)Possible Reconnaissance

ECOLE NATIONALE SUPERIEURE UNIVERSITE DES SCIENCES DES SCIENCES DE L'INFORMATION SOCIALES GRENOBLEII ETDES BIBLIOTHEQUES INSTITUT D'ETUDES POLITIQUES D.ES.S. Direction de projets culturels MEMOIRE Marianne OSWALD, vers une (im)possible reconnaissance Michel BOLCHERT sous la direction de C6cile MEADEL Centre de sociologie de Vinnovation, Paris 1992 Marianne OSWALD, vers une (im)possible reconnaissance Michel BOLCHERT RESUME : Comment une personnalite, comme celle de Marianne OSWALD (1901-1985) chanteuse, actrice, productrice d'emissions radiophoniques et televisisees, peut-elle devenir l'enjeu d'une politique culturelle locale? L'auteur situe la problematique au croisement de la reconnaissance d'une demarche artistique et de son inscription dans un contexte defini. DESCRIPTEURS : OSWALD (Marianne) Marianne OSWALD with an aim to (im)possible recognition Michel BOLCHERT ABSTRACT : How a personality, such as that of Marianne OSWALD (1901-1985), singer, actress, producer of radio and television shows, becomes the battleground in local cultural politics ? The autor is attempting to define a project in a particular context. KEYWORDS : OSWALD (Marianne) SOMMAIRE ... vous avez dit Marianne OSWALD? p. 2 (limincdres) 1. MARIANNE OSWALD, ab£c£daire p. 4 2. MARIANNE OSWALD, productions p. 29 3. MARIANNE OSWALD, 1'interprete : 1932-1938 p. 30 3. 1. Quelques points de repere : essai de chronologie p. 33 3. 2. L'art de Marianne OSWALD, interprete 2. 1. Genealogie d'une voix p. 38 2. 2. Le choix des textes p. 42 2. 3. Marianne OSWALD, chanteuse p. 43 3. 3. Marianne OSWALD, discographie p. 44 3. 4. Marianne OSWALD, actrice de cinema p. 46 4. MARIANNE OSWALD, la productrice (1951-1974) p. -

Marianne Oswald, Vers

Marianne Oswald »)<£• r> c A^dxo Vues d e Presse ar o»l <fc> AMb J)$£> b A^txe» oreye rencontre avec... Marianne OSWALD dans sa ville natale C cst toujours avcc la mcmc joie chainement h Sarrcguemincs, Ma juvcnile quc Marianne Oswald rc- rianne ? trouvc Sarrcguemines, ou ellc cst nee — Sans doute, mais pas a 1'occn- ct ou clle passa une grande partie sion de l cmission publiquc. de son cnfance. Mariannc Oswald est catcgoriquc. Nous 1 avons rctrouvce samcdi aoir Ejle yicnt de revenir sur la premicre attablce au cafe Alcx Uouvcl. ruc dccision la suite d'un entrcticn Saintc-Croix, ou clle cst vcnue rc- avcc lc president du Syndicat d'lni- clierchcr ccttc atmosphere si sympa- tialivcs dc Sarrcguemincs cjui orga- thiauc du pctit cafe, ou, a I hcure ni8c cctte cmission. Elle cstime n'a- de rapcritif, le commcr^ant du coin voir pas rencontre toute la compre- vicnt s attablcr a cote de 1'ouvriet a hension compatiblc avec le role de sa sortic de 1'atclier, ou la boulrgcoi- vcdctte qui |ui rcvenait dc droit. car sie sc confond avec le proletariot cn Marianne Oswald constitutait incon- une bruyonte harmonie. testablcment unc attraction de tout premier ordrc pour cette soirce # — C'est gcntil ici, nous dit-clle cn s'attablant. ~~ II nc s agit pas d'une question — Qucl bon vcnt vous anicne, d argent, prccise Marianne Oswald. qucstionnons-nous ? Je n avais d'aillcurs pose aucunc < J'ai rc^u unc invitation de Radio- condition a ma venuc a SorreRue- Lorrainc pour participer k la grandc mines.