Cyprus Question’: Reshaping Community Identities and Elite Interests Within a Wider European Framework CEPS Working Document No

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Description of the Historic Monuments of Cyprus. Studies in the Archaeology and Architecture of the Island

Cornell University Library The original of this book is in the Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924028551319 NICOSIA. S. CATHARINE'S CHURCH. A DESCRIPTION OF THE Historic iftlonuments of Cyprus. STUDIES IN THE ARCHEOLOGY AND ARCHITECTURE OF THE ISLAND WITH ILLUSTRATIONS FROM MEASURED DRAWINGS AND PHOTOGRAPHS. BT GEORGE JEFFERY, F.S.A., Architect. * * * * CYPRUS: Printed by William James Archer, Government Printer, At the Government Printing Office, Nicosia. 1918. CONTENTS. ILLUSTRATIONS. Frontispiece. S. Catharine's Church facing Title . Page Arms of Henry VIII. or England on an Old Cannon . 1 Arms of de L'Isle Adam on an Old Cannon St. Catherine's Church, Nicosia, South Side Plan of Nicosia Town St. Catherine's Church, Nicosia, Plan . „ ,, „ Section Arms of Renier on Palace, Famagusta . Sea Gate and Cidadel, Famagusta Citadel of Famagusta, Elevations ,. Plans Famagusta Fortifications, The Ravelin Ancient Plan of a Ravelin Famagusta Fortifications, Moratto Bastion ,, „ Sea Gate ,, „ St. Luca Bastion St. George the Latin, Famagusta, Section Elevation Plan Plan of Famagusta Gates of Famagusta Church of Theotokos, Galata „ Paraskevi, Galata „ Archangelos, Pedoulas Trikukkia Monastery. Church of Archangelos, Pedoulas Panayia, Tris Elijes Plan of Kyrenia Castle Bellapaise, General Plan . „ Plan of Refectory „ Section of Refectory „ Pulpit in Refectory St. Nicholas, Perapedi Ay. Mavra, Kilani Panayia, Kilani The Fort at Limassol, Plan . SHOET BIBLIOGEAPHY. The Principal Books on Cyprus Archeology and Topography. Amadi, F. Chronicle (1190-1438) Paris, 1891. Bordone, B. Isolario Venice, 1528. Bruyn, C. de, Voyage (1683-1693) London, 1702. -

Dodecanese GREECE

GREECE Dodecanese www.visitgreece.gr GREEK NATIONAL TOURISM ORGANISATION 04Patmos 34Kos 68Chalki 12Agathonisi 44Astypalaia 72Rhodes (Rodos) 14Leipsoi (Lipsi) 52Nisyros 86Karpathos 16Leros 60Tilos 96Kasos Kastellorizo 24Kalymnos 64Symi 100(Megisti) CONTENTS Cover Page: Approaching Armathia, an uninhabited islet, near Kasos. 1. Elaborate pebble mosaic floors, an integral part of the Dodecanesian tradition. 1. The Dodecanese 2. Dodecanese’s enchanting beaches are one of the main attractions for millions of tourists every year. The Dodecanese island group is in the southeastern part of the Aegean Sea, the sunniest corner of Greece; it comprises twelve large islands and numerous smaller ones, each one with a different character. You will find fantastic beaches, archeological sites of great historical impor- tance, imposing Byzantine and Medieval monuments, traditional villag- es and architectural gems that date to the Italian Occupation. The Do- decanese have long been one of the most popular tourist destinations in the Mediterranean. Rhodes and Kos, are among the largest islands of the group and the two most popular ones. Karpathos, Patmos, Leros, Symi, Kalymnos, and Astypalaia have managed to keep their traditional flavour despite the fact that large numbers of tourists visit them. The smaller islands, with lower rates of growth, like Tilos, Nisyros, Leipsoi, Chalki, Kasos, Kastel- lorizo, Agathonisi, Telendos and Pserimos are a fine choice for relaxed and peaceful holidays. These islands have a rich and very long history. They have known pirate raids and have been occupied by the Knights Hospitaller, the Turks, and the Italians, to be eventually integrated in Greece in 1948. PATMOS 3. Skala, Patmos’ port. Chora lies in the background. -

Cyprus Gazette Κindex Ο for the Year 1886Μ

ΙΑ Τ Α Ρ Κ Ο Μ Η "<y \- .1 i '•• .-l. Δ Η Κ ΙΑ Ρ Π Υ Κ ΙΑ Τ Α Ρ Κ Ο Μ Η Δ Η Κ ΙΑ Ρ Π Υ Κ x » • 1,:}%S t P> nP^^^^^ <SS4^^">;: , ΙΑ Τ Α THE Ρ CYPRUS GAZETTE ΚINDEX Ο FOR THE YEAR 1886Μ. Η Δ Published by Authority. Η Κ Α Ι PRICE ONB SHILLING. Ρ Π Υ PRINTED AT THE GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE. NICOSIA. Κ 3ns^ ΙΑ Τ Α Ρ Κ Ο Μ The Editor of ''The Cypn/.s Gazette"Η irill be glad lo receive corrertions of any errors or onmsions that mag be discorcred in this Index. Δ Η Κ ΙΑ Ρ Π Υ Κ THE CYPRUS GAZEHE INDEX, 1886. ΙΑ Page P»ge A Andoni, Vassihou Hadji Τ Murder of ... ... ... ••• 838 Abdulhamid Percentage on Yoklama Foes due to ... ... 808 Animal Diseases, see "Contagious Discasfs Accomits (Animals)." Α Revenue and Expenditure, 1885-86 ... ... 814 Animals Examiner of, see "Audit O^ce." Cruelty to. Draft Law for prevention of 719 Acts, Imperial Slaughter of, Municipal Bye-Laws respecting. >?!« Medical Acts Amendmeut Aot ... ... 842 -Municipcd Councils. Evidence by Commission Acts extended to Cyprus 877 Ρ Appropriation Laws Foreign Deserters' Aot. 185"2. extended to the Supplementary, 1884-85. Confirmed by Her Majestv 719 Republic of the Equator and the Oriental 1885-86 ... ... 767.773. ^13 Republic of Uruguay ... ... ... 883 1886-87 ... ... ... 757.773. 813 Adem Iskender, see '^Iskender." Supplementary. 1886-8Κ7 ... ... 773. S13 Administration of Estates Arirates Infants" Estates Law Amendment Law, 188o 733. 773. Survey of .. -

Items-In-Cyprus - Chronological Files

UN Secretariat Item Scan - Barcode - Record Title 1 23 Date 15/06/2006 Time 9:27:40 AM S-0903-0007-03-00001 Expanded Number S-0903-0007-03-00001 items-in-Cyprus - chronological files Date Created 05/02/1980 Record Type Archival Item Container S-0903-0007: Peackeeping - Cyprus 1971-1981 Print Name of Person Submit Image Signature of Person Submit f ;• 5 cvrc- ' /> -f P ^~~ j \ ( / '--RECEIVED Unn v&*( S CylI ~~~' MOV 2 71981 PERMANENT MISSION OF THE REPUBLIC OF CYPRUS •' '•' •-'-•' TO THE UNITED NATIONS 13 EAST 4OTH STREET NEW YORK. N. Y. 1OO10 . / ...-,, _-/_•» -.' ""/""" TEL: (212) 686.6O16 ,,1 f i L-- ''•' - " I 27 November 1981 -^ /-. ,-, '--..._-- » -|- Excellency, Upon instructions from my government, I have the honour to draw Your Excellency's attention and that of the membership of the Security Council to the decision taken by the Turkish - Cypriot leadership to confer "citizenship" of the so called "Turkish Federated State of Cyprus" to Turkish settlers from Turkey . According to Turkish Cypriot newspaper reports (OLAY of 9 November 1981) and verified information received by authorities of the government of the Republic of Cyprus, the Turkish - Cypriot leadership has Specified "Special cases of eligibility for citizen- ships of the "Turkish Federated State of Cyprus". 'The new amend- ment to the law, annexed hereto, is dated 28 October 1981 and is published in the "Official gazette No. 107". As Your Excellency is well aware the "Turkish Federated State of Cyprus" is a fictitious entity whose establishment was regretted by the Security Council in its resolution 367 of 12 May, 1975. -

Government Commodities Distribution) Order, 1943

No. 6. THE DEFENCE (GOVERNMENT COMMODITIES DISTRIBUTION) ORDER, 1943. AUTHORIZATION UNDER CLAUSE 2. It is hereby notified for general information that I have authorized the following persons and bodies to sell and distribute charcoal and fuelwood within the following areas :— Name of Person or Body : Area : Fuel and Charcoal Controller. Nicosia District. Kyrenia District. Larnaca District. Famagusta District. Paphos District. Limassol District; Municipal Corporation of Limassol Limassol town. ,, of Kyrenia Kyrenia town and villages of Thermia, Aghirda, Krini, Pileri, Keumurju, Karmi, Trimithi, Ayios Yeoryios, Temblos. of Morphou Morphou village and villages of Kalokhorio (Kapoiiti), Syriano- khori, Khrysiliou, Kyra, Philia, Prastio, Nikitas, Argaki, Masari, Katokopia, Kato Zodhia, Pano Zodhia, Astromeritis, Avlona, Peristerona. of Lapithos Lapithos village, and villages of Karavas, Elea, Motidhes, Phte- rykha, Paleosophos, Sisklipos, Agridhaki, Larnaka, Vasilia. of Lefka Lefka village and villages of Peri- steronari, Eloa, Kalokhorio, Ayios Yeoryios, Ayios Nikolaos, Apliki. of Polis Polis village. of Lef koniko Lef koniko village and villages of Prastio, Maratha, Peristerona, Piyi, Milea, Gypsos, Lapathos, Syngrasi, Gouphes, Knodhara, Chatos, Vitsadha, Psilatos, Ma• ra thovouno, Yenagra, Pyrga. of Kythrea Kythrea village and villages of Khrysidha, Bey Keuy, Neokhorio, Voni, Epikho, Trakhoni, Exo- metokhi, Palekythro. Co-operative Credit Society of Dhiorios Dhiorios village and villages of Myrtou, Karpasha, Kambyli, Asomatos, Ayios Ermolaos, Kon- demcnos, Photta, Dhyo Potami, Skylloura, Ayios Vasilios, Ayia Marina. ofAthienou . Athienou village. of Agros Agros village. Co-operative Store of Lysi Lysi village and villages of Mou- soulita. Strongylos, Asha, Aphania, Sinda, Vatili, Kondea, Kouklia. Co-operative Savings Bank Ltd. of Pedhoulas Pedhoulas village. Co-operative Credit Society of Yialousa-Ayia Trias. -

ΚΟΙΝΟΤΙΚΟ ΣΥΜΒΟΥΛΙΟ ΜΑΣΣΑΡΙ Twining of Massari Cyprus and Masari Rhode

ΚΟΙΝΟΤΙΚΟ ΣΥΜΒΟΥΛΙΟ ΜΑΣΣΑΡΙ MASSARI COMMUNITY COUNCIL Τήνου 4, 2301 Λακατάµεια, Λευκωσία / 4 Tinou Street, CY-2301 Lakatamia, Nicosia Τηλ./ Tel.: 99 67 3025, Email: [email protected] Twining of Massari Cyprus and Masari Rhode In January 16-22, 2009 a delegation from Masari Restaurant in Kokkinotrimithia. The event Rhode constituted from the Chair of the Community honoured with their presence the Bishop of Morfou Council of Masari Mr Christo Nikita, Municipal Council member of Archangelos Municipality and chair of “Kammyri” association Mr Panayioti Metropolis, the Minister of Internal Affairs, the Mastrosavvaki, the representatives of the Mayor of Morfou, representatives of the Sub- Ecclesiastical Committee and citizens of Masari prefect Nicosia office, the Chair of the Nicosia villagers numbered to 38. All participated in a Occupied Communities, Chairs of the Community series of events organized by the Community Councils of other villages in the region as well as a Council of Massari village in Cyprus and the great number of friends, relatives and people from Massari Athletic Union in the frame of promoting the the occupied community Massari. processes of twining the two homonym The event addressed the Bishop of Morfou communities. Metropolis Neophytos, the Minister of Internal The group from Rhode was warmly welcomed by a Affairs Mr Neoclis Sylikiotis, the Chair of the representation team on Friday January 16 th . Community Council of Massari Dr Eleftherios They participated as officials on Saturday afternoon Antoniou, the Mayor of Morfou Mr Charalambos at the church service offered at St Antonio Chapel in Pittas, the Chair of the Chair of the Community Peristerona and were offered breakfast by the Council of Masari Rhode Mr Christos Nikitas. -

No, 443. the ELEMENTARY EDUCATION LAW

4o7 No, 443. THE ELEMENTARY EDUCATION LAW. CAP. 203 AND LAWS 22 OF 1950 AND 17 OF 1952. ORDER UNDER SECTION 6 (2). A. B. WRIGHT, Governor. ν In exercise of the powers vested in me by section 6 (2) of the" Elementary Education Law, I, the Governor > do hereby order as follows :— Cap. 203 ^ 22 of 1950 17 of 1952 1. This Order may be cited as the Elementary Education (Prescription Gazette: of Groups) (Amendment) Order, 1952, and shall be read as one with the Suppl.No.3: 2 ,9 1951 Elementary Education (Prescription of Groups) Order, 1951 (hereinafter · referred to as "the principal Order"), and the principal Order and this Order may together be cited as the Elementary Education (Prescription of Groups). Orders, 1951 and 1952. ' 2. Clause 2 of the principal Order is hereby amended by the deletion therefrom of the figure "86" in line 5 and the substitution therefor of the figure " 87 ". 3. The First Schedule to the principal Order is hereby amended as follows:— - ■ ■ .. ; ., by the insertion therein immediately after the words " Moslem. Zakaki.: Limassol" of the following words in their respective columns, i.e. " Moslem. Phasoula. Limassol" and the words "Greek-Orthodox. Rrysiliou. Morphou ". ■■'...; 4. The Second Schedule to the principal Order is hereby amended as follows :■— (a) by the deletion therefrom of the words " Morphou-Khrysiliou ", " Philia-Masari" in column 2 under the heading " Nicosia District ", of the words " Akoursos-Kathikas ", " Dhrousha-Inia ", " Timi- Mandria " in column 2 under the heading " Paphos District" in respect of the Greek-Orthodox' religious community, and (b) by the deletion therefrom of the words " Argaki-Morphou " in column 2 under the heading " Nicosia District " and of the words " Ayios Epiktitos-Klepini" in column 2 under the heading , " Kyrenia District " in respect of the Moslem religious community. -

Authentic Route 10

Cyprus Authentic Route 10 Safety Driving in Cyprus Comfort Rural Accommodation Tips Useful Information Only DIGITAL Version Ecclesiastical Treasures Lefkosia • Strovolos • Kato and Pano Deftera • Psimolofou • Episkopio • Politiko-Tamassos • Pera • Kampia • Kapedes • Machairas Monastery • Lazanias • Gourri • Fikardou • Klirou • Malounta • Agrokipia • Mitsero • Platanistasa • Fterikoudi • Askas • Palaichori • Alona • Polystypos • Lagoudera • Xyliatos • Agia Marina • Orounta • Peristerona • Akaki • Kokkinotrimithia • Lefkosia Route 10 Lefkosia – Strovolos – Kato and Pano Deftera – Psimolofou – Episkopio – Politiko-Tamassos – Pera – Kampia – Kapedes – Machairas Monastery – Lazanias – Gourri – Fikardou – Klirou – Malounta – Agrokipia – Mitsero – Platanistasa – Fterikoudi – Askas – Palaichori – Alona – Polystypos – Lagoudera – Xyliatos – Agia Marina – Orounta – Peristerona – Akaki – Kokkinotrimithia – Lefkosia scale 1:350,000 Skylloura Agia Kanli Mandres Kioneli 0 1 2 4 6 8 Kilometers Marina Agios Kyra Vasileios Morfou Mia Ortakioi Milia Masari Argaki Fyllia Gerolakkos Trachonas Kato Mammari Agios Katokopia Deneia Nikitas Zodeia Dometios Pano Nicosia International Egkomi Aglantzia Zodeia Avlona Kokkinotrimithia Airport (Not in use) Astromeritis Akaki Strovolos Peristerona Agioi Angolemi Palaiometocho Lakatameia Trimithias Geri Potami Orounta Meniko Anthoupoli Latsia Pano Kato Koutrafas Pano Panagia Koutrafas Deftera Chrysospiliotissa Nikitari Agios Kato Kato Agios Deftera Vyzakia Agioi Ioannis Anageia Tseri Moni Panteleimon Vyzakia Iliofotoi -

Pagemaker Econ Stat 2003 300805

ȀȊȆȇǿǹȀǾ ǻǾȂȅȀȇǹȉǿǹ REPUBLIC OF CYPRUS ȈȉǹȉǿȈȉǿȀȅǿ ȀȍǻǿȀȅǿ ǻǾȂȍȃ, ȀȅǿȃȅȉǾȉȍȃ Ȁǹǿ Ǽȃȅȇǿȍȃ ȉǾȈ ȀȊȆȇȅȊ STATISTICAL CODES OF MUNICIPALITIES, COMMUNITIES AND QUARTERS OF CYPRUS 2010 ȈȉǹȉǿȈȉǿȀǾ ȊȆǾȇǼȈǿǹ STATISTICAL SERVICE ȈIJĮIJȚıIJȚțȠȓ ȀȦįȚțȠȓ: x ȈİȚȡȐ ǿ x ǹȡ. DzțșİıȘȢ 6 Statistical Codes: x ȈİȚȡȐ ǿ x Report No 6 - 3 - ȆȇȅȁȅīȅȈ PREFACE ǹȣIJȒ İȓȞĮȚ Ș ȑțIJȘ ȑțįȠıȘ IJȠȣ įȘµȠıȚİȪµĮIJȠȢ This is the sixth edition of the publication “Statistical «ȈIJĮIJȚıIJȚțȠȓ ȀȦįȚțȠȓ ǻȒµȦȞ, ȀȠȚȞȠIJȒIJȦȞ țĮȚ ǼȞȠȡȚȫȞ Codes of Municipalities, Communities and Quarters of IJȘȢ ȀȪʌȡȠȣ» țĮȚ ʌĮȡȠȣıȚȐȗİȚ IJȠ ĮȞĮșİȦȡȘµȑȞȠ Cyprus” and it presents the updated statistical coding ıIJĮIJȚıIJȚțȩ țȦįȚțȩ ıȪıIJȘµĮ IJȦȞ IJȠʌȚțȫȞ İįĮijȚțȫȞ system of the local territorial units (municipalities, µȠȞȐįȦȞ (įȒµȦȞ, țȠȚȞȠIJȒIJȦȞ țĮȚ İȞȠȡȚȫȞ) IJȘȢ ȀȪʌȡȠȣ. communities and quarters) of Cyprus. The revised ȉȠ ĮȞĮșİȦȡȘµȑȞȠ ıȪıIJȘµĮ ȖİȦȖȡĮijȚțȫȞ țȦįȚțȫȞ geographical coding system was prepared in ȑȖȚȞİ ıİ ıȣȞİȡȖĮıȓĮ µİ ȐȜȜİȢ ĮȡµȩįȚİȢ ȊʌȘȡİıȓİȢ țĮȚ collaboration with other competent Services and ȉµȒµĮIJĮ țĮȚ ıIJȠȤİȪİȚ ıIJȘȞ İȣȡȪIJİȡȘ įȣȞĮIJȒ ȤȡȒıȘ. Departments and aims at its broadest possible use. Ǿ ȖİȦȖȡĮijȚțȒ IJĮȟȚȞȩµȘıȘ ʌİȡȚȜĮµȕȐȞİȚ IJȚȢ įȚȠȚțȘIJȚțȑȢ The geographical classification pertains to the İʌĮȡȤȓİȢ, IJȠȣȢ įȒµȠȣȢ, IJȚȢ țȠȚȞȩIJȘIJİȢ țĮȚ IJȚȢ İȞȠȡȓİȢ. administrative districts, the municipalities, the ȉĮ ȠȞȩµĮIJĮ IJȦȞ įȒµȦȞ/țȠȚȞȠIJȒIJȦȞ țĮȚ İȞȠȡȚȫȞ İȓȞĮȚ IJĮ communities and the quarters. The names of İʌȓıȘµĮ ȠȞȩµĮIJĮ µİ IJȘ ȖȡĮijȒ ȩʌȦȢ țĮșȠȡȓıIJȘțİ Įʌȩ municipalities/communities and quarters are the official IJȘ ȂȩȞȚµȘ ȀȣʌȡȚĮțȒ ǼʌȚIJȡȠʌȒ ȉȣʌȠʌȠȓȘıȘȢ names which have been determined by the Cyprus īİȦȖȡĮijȚțȫȞ ȅȞȠµȐIJȦȞ ıIJȘȞ ǼȜȜȘȞȚțȒ ȖȜȫııĮ țĮȚ IJȘ Permanent Committee for the Standardization of µİIJĮȖȡĮijȒ IJȠȣȢ ıIJȠ ȇȦµĮȞȚțȩ ĮȜijȐȕȘIJȠ. Geographical Names in the Greek language and transliterated in Roman characters. ĬĮ ʌȡȑʌİȚ ȞĮ ıȘµİȚȦșİȓ ȩIJȚ IJȠ țȦįȚțȩ ıȪıIJȘµĮ It should be noted that the coding system covers the țĮȜȪʌIJİȚ ȠȜȩțȜȘȡȘ IJȘȞ ȀȪʌȡȠ, įȘȜ. -

Local VFR Chart Larnaka

LOCAL VFR CHART TWR 130.2 MHz GMC 119.4 MHz LARNAKA APP 130.2 MHz ATIS 126.55 MHz E03310 E03320 E03330 E033 40 E03350 T Mousoulita LEGEND Argaki MasariFilia 860 T Pyrga Katokopia Gerolakkos T Mora Mammari Prastio N35 Avlona T N35 Dheneia Strongylos Gaidouras 10 Kato Zodia (92) 10 AfaneiaAssia Sinta NBD T Kokkinotrimithia T Astromeritis T LEFKOSIA 0 T 9 7 T Akaki 2 T Tymvou T Vatili VOR/DME ROSE T Peristerona BUFFER 18 T T T T T Paliometocho T ZONE T T LCR 01 T 19 Meniko T T Agioi TrimithiasT 6 GROUP OF OBSTACLES LIGHTED 4 T T G T Agios Nikolaos LCD 18 Geri Kouklia Latsia Lysi Orounda T 27 Kontea Koutrafas T T WIND TURBINE GROUP T Kalopsida G T 1130 T T 34 LC TRA08 Deftera Arsos 1235 Tremetousia Tseri VFR REPORTING POINT Vyzakia Anageia 54 1145 1772 LCD 20 Makrasyka G Athienou RESERVOIR Kato Moni VYZAKIA DAM Agios Panteleimon T Ergates Psimolofou ACHNA DAM DANGER AREA 1760 T Agia Marina Xyliatou Pergamos 2110 Agrokipia LCD 6 Achna (633) 2025 Arediou LC TSA06 T Petrofani TEMPORARY SEGREGATED AREA T Potamia Mitsero KLIROU DAM LC TSA07 Achna Malounta Marki G&M Props T 2225 Politiko Pera KL and Gears RC Models Troulloi Xyliatos Agios AL IRO T Marki T LCD 43 ER U Xylotympou Iraklidios NA TE TEMPORARY RESERVED AREA Klirou Marki Microlight Dali LC TSA02 1605 Agios Ioannis 1195 Marki Air Model Kalo Chorio 1465 Strip LC TRA02 3120 TAMASOS DAM LCD 7 G Analiontas XYLIATOS DAM Kotsiatis T 2165 Kampia T T T Agios Epiphanios Lympia T N35 G N35 1850 TRAINING AREA (CLASS G) BOUNDARIES T T TPyla T 00 3300 T 1130 T 331 00 KLIROU Agia Varvara T LC TSA08 -

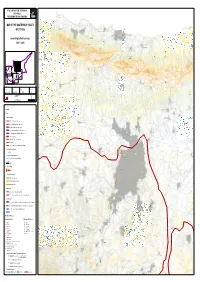

MAP of the QUATERNARY FAULTS of CYPRUS According to Field

STUDY OF ACTIVE TECTONICS IN CYPRUS FOR SEISMIC RISK MITIGATION VAVYLAS MAP OF THE QUATERNARY FAULTS OF CYPRUS VASILEIA AGIOS GEORGIOS KERYNEIAS KARAVAS LAPITHOS KARAKOUMI TEMPLOS KERYNEIA MOTIDES ELIA KERYNEIAS according to field surveys PANAGRA TRIMINTHI 2001 - 2005 THERMEIA PALAIOSOFOS FTERICHA AGIOS EPIKTITOS CHARKEIA KARMI KAZAFANI LARNAKAS LAPITHOU MYRTOU KLEPINI TRAPEZA AGRIDAKI BELAPAIS DIORIOS KAMPYLI SYSKLIPOS KARPASEIA AGIRTA CENTRAL MESAORIA KIOMOURTZOU PILERI NORTH-WESTERN CYPRUS KRINI SOUTH-EASTERN CYPRUS CENTRAL CYPRUS PANO DIKOMON SOUTH-WESTERN CYPRUS ASOMATOS KERYNEIAS AGIOS ERMOLAOS SINCHARI VOUNON KONTEMENOS KATO DIKOMON KOUTSOVENTIS FOTA Version: Report: Scale: Format: September 14, 2005 GTR/CYP/0905-170 1/ 50 000 A0 KALYVAKIA 3, rue Jean Monnet 34830 Clapiers ^ Tél : (33) 04 67 59 18 11 0 500 1 000 1 500 2 000 Fax : (33) 04 67 59 18 24 Mètres KYTHREA CHRYSIDA BEYKOY Legend NEON CHORION KYTHREAS PETRA TOU DIGENI SKILLOURA Faults VONI Quaternary faults EPICHO TRACHONI LEFKOSIAS AGIA MARINA SKILLOURAS KOUROU MONASTIRI Fault with Quaternary displacement AGIOS VASILEIOS KANLI Inferred fault with Quaternary displacement EXO METOCHI Older fault with Quaternary displacement MANDRES LEFKOSIAS Older fault with inferred Quaternary displacement GONYELI MIA MILIA PALAIKYTHRON ORTAKOY Inferred fault with inferred Quaternary displacement KYRA Fault scarp, scarplet MIA MILIA INDUSTRIAL AREA ### Faulting within Plio quaternary deposits TRACHONAS #### Reverse fault FYLLIA *# !( *# Frontal evidence of uplift, produced by blind thrusting -

CHRISTIAN MONUMENTS of CYPRUS Under Turkish Military Occupation Map Sections

CHRISTIAN MONUMENTS OF CYPRUS Under Turkish Military Occupation “ And when they had gone through the isle unto Paphos, they found a certain sorcerer, a false prophet, a Jew, whose name was Bar-jesus: which was with the deputy of the country, Sergius Paulus, a prudent man; who called for Barnabas and Saul, and desired to hear the word of God. But Elymas the sorcerer (for so is his name by interpretation) withstood them, seeking to turn away the deputy from the faith. Then Saul (who is also called Paul), filled with the Holy Ghost, set his eyes on him, And said, O full of all subtlety and all mischief, thou child of the devil, thou enemy of all righteousness, wilt thou not cease to pervert the right ways of the Lord? And now, behold, the hand of the Lord is upon thee, and thou shalt be blind, not seeing the sun for a season. And immediately there fell on him a mist and a darkness; and he went about seeking some to lead him by the hand. Then the deputy, when he saw what was done, believed, being astonished at the doctrine of the Lord. “ Acts 13:6-12 The Conversion of the Proconsul – Raphael, 1515-16 CONTENTS Monastery of Profitis Elias, Ayia Marina Skilloura. Church of Chrysopolitissa, Kyrenia Town. Map Sections 06 About the Project 07 Section A’ 08 Section B’ 10 Section C’ 12 Section D’ 14 Section E’ 16 Section F’ 18 Section G’ 20 The entrance of the church Agios Andronikos, in Kythrea. Monastery of Agios Panteleimon in Myrtou.