An Introduction to Late Mediaeval Logic and Semantic Theory

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AWARDS 3X PLATINUM ALBUM February // 2/1/17 - 2/28/17

RIAA GOLD & PLATINUM HAMILTON//BROADWAY CAST AWARDS 3X PLATINUM ALBUM February // 2/1/17 - 2/28/17 BRUNO MARS//24K MAGIC PLATINUM ALBUM In February 2017, RIAA certified 70 Digital Single Awards and 22 Album Awards. All RIAA DIERKS BENTLEY//BLACK GOLD ALBUM Awards dating back to 1958, plus #RIAATopCertified tallies for your favorite artists, are available at DAVID BOWIE//BLACKSTAR GOLD ALBUM riaa.com/gold-platinum! KENNY CHESNEY//THE BIG REVIVAL SONGS GOLD ALBUM www.riaa.com //// //// GOLD & PLATINUM AWARDS FEBRUARY // 2/1/17 - 2/28/17 MULTI PLATINUM SINGLE // 13 Cert Date// Title// Artist// Genre// Label// Plat Level// Rel. Date// X 21 Savage & Metro R&B/ 2/22/2017 Slaughter Gang, LLC 7/15/2016 (Feat. Future) Boomin Hip Hop R&B/ Waverecordings/Empire/ 2/3/2017 Broccoli D.R.A.M. 4/6/2016 Hip Hop Atlantic R&B/ Waverecordings/Empire/ 2/3/2017 Broccoli D.R.A.M. 4/6/2016 Hip Hop Atlantic 2/22/2017 This Is How We Roll Florida Georgia Line Country BMLG Records 12/4/2012 Jidenna Feat. Ro- R&B/ 2/2/2017 Classic Man Epic 2/3/2015 man Gianarthur Hip Hop Last Friday Night 2/10/2017 Katy Perry Pop Capitol Records 8/24/2010 (T.G.I.F) 2/3/2017 I Don’t Dance Lee Brice Country Curb Records 2/25/2014 Lil Wayne, Wiz Khal- ifa & Imagine Drag- R&B/ 2/1/2017 Sucker For Pain ons With Logic And Atlantic Records 6/24/2016 Hip Hop Ty Dolla $Ign (Feat. X Ambassadors) My Chemical 2/15/2017 Teenagers Alternative Reprise 10/20/2006 Romance 2/21/2017 Bad Blood Taylor Swift Pop Big Machine Records 10/27/2014 2/21/2017 Die A Happy Man Thomas Rhett Country Valory Music Group 9/18/2015 2/17/2017 Heathens Twenty One Pilots Alternative Atlantic Records 6/17/2016 Or Nah R&B/ 2/1/2017 (Feat. -

Power Gold: 2013’S Ins & Outs for the Second Consecutive Year, Country’S Top 100 Power Gold List Displays a Lot of Turnover from the Previous 12 Months

April 29, 2013, Issue 343 Power Gold: 2013’s Ins & Outs For the second consecutive year, Country’s Top 100 Power Gold list displays a lot of turnover from the previous 12 months. This year’s Top 100 boasts 22 new titles, compared to a whopping 33 in our April 2012 analysis and 13 new tunes in July 2011. This year’s Top 10 Power Gold is culled from Mediabase 24/7 and the Country Aircheck/Mediabase reporting panel for the week of April 21-27: 1. Kid Rock/All Summer Long 2. Zac Brown Band/Chicken Fried 3. Keith Urban/Somebody Like You 4. Alan Jackson & Jimmy Buffet/It’s Five O’Clock Somewhere 5. Dierks Bentley/What Was I Thinkin’ 6. Zac Brown Band/Toes 7. Rodney Atkins/Watching You Keith Urban Man, What Are You Doing Here? Rodeowave’s Phil Vassar (c) invites KSON/San Diego’s John & Tammy on stage while he 8. Rascal Flatts/Life Is A Highway plays “Piano Man” at the Stagecoach Country Music Festival in 9. Joe Nichols/Gimmie That Girl Indio, CA Saturday (4/27). 10. Rodney Atkins/If You’re Goin’ Through Hell New to the Top 10 are the ZBB, Flatts and Atkins tunes. Pope Finds Her Voice Sliding out of the Top 10 were Darius Rucker’s “Alright” She brought a pop-rock background and sound to The (16); Carrie Underwood’s “Before He Cheats” (15) and Voice’s Team Blake, but Cassadee Pope is now readying James Otto’s “Just Got Started Lovin’ You” (20). her Republic Nashville country debut. -

Country Superstar Kenny Chesney to Rock the 4Th of July at the 2013 Greenbrier Classic Concert Series

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE FEBRUARY 20, 2013 COUNTRY SUPERSTAR KENNY CHESNEY TO ROCK THE 4TH OF JULY AT THE 2013 GREENBRIER CLASSIC CONCERT SERIES [White Sulphur Springs, WV] The Greenbrier, the classic American resort in White Sulphur Springs, WV, has announced that country music superstar Kenny Chesney will top a star-studded musical lineup at The Greenbrier Classic Concert Series, July 1-7, 2013, coinciding with the resort's fourth annual PGA TOUR FedExCup Event, The Greenbrier Classic. Kenny Chesney, a four-time Country Music Association and four-consecutive Academy of Country Music Entertainer of the Year, as well as the fan-voted American Music Awards Favorite Artist, is known for his high-energy concerts that regularly sell out NFL stadiums. Having recorded 19 #1s, including the multiple week chart-toppers "There Goes My Life," "Summertime," "Living in Fast Forward," "You & Tequila" and "When the Sun Goes Down," the man who's sold almost 30 million albums has become the sound of summer, good times and good friends for the 21st century. "This country is an amazing place," says Chesney. "I can see it every night at my shows: all the heart, the passion and the fun I can see out in the crowd. And to be able to spend the 4th of July somewhere as historic as The Greenbrier, that's a pretty incredible place to celebrate our nation's birthday!" "We couldn't be happier to have an American superstar like Kenny Chesney to top the bill at our Greenbrier Classic concert series," says Jim Justice, owner of The Greenbrier. -

Přírůstkový Seznam

aktualizace Rok Př. číslo Autor, interpret Název alba, kompilace ©℗ CDs X domů od: 31 873 5 Seconds of Summer 5 Seconds of Summer 2014 CD 31 512 Accept Eat the heat 2002 CD 31 473 ACDC Ballbreaker 1995 CD 31 472 ACDC Powerage 1978 CD 31 279 Adair, Beegie (+Pat Coil) Cocktail party jazz 2011 CD 31 954 Adamec, Radek Bubákov 2015 CD 5.8.2016 31 954 Adamec, Radek Bubákov 2015 CD 5.8.2016 31 571 Adamec, Radek Veselé mašinky : pohádky z depa a kolejí 2013 CD 32 109 Adele 25 2015 CD 20.8.2016 32 103 Adler-Olsen, Jussi Vzkaz v láhvi 2015 CD 2 21.9.2016 31 751 Adler-Olsen, Jussi Zabijáci : předloha filmového thrilleru 2015 CD 12.1.2016 31 280 Aiken, Clay A thousand different ways 2006 CD 31 281 Aiken, Clay Measure of a man 2003 CD 31 675 Albarn, Damon Everyday robots 2014 CD 31 391 Aldort, Naomi Vychováváme děti a rosteme s nimi 2014 CD 31 967 Aleš Brichta Project Anebo taky datel 2015 CD 11.3.2016 31 130 Aleš Brichta Project Údolí sviní 2013 CD 31 397 Allen, Lily Sheezus 2014 CD 32 110 Allison, Bernard In the mix 2015 CD 16.10.2015 32 263 Allman, Gregg All my friends : celebrating the songs & 2014 CD 2 voice of Gregg Allman 32 206 Allman, Gregg Laid back 1973 CD 32 264 Allman, Gregg Low country blues 2011 CD 31 513 Alter Bridge Fortress 2013 CD 31 155 Al-Yaman Insanyya 2009 CD 31 851 Anderson, Jon The Promise ring 1997 CD 31 715 Anderson-Lopez, Kristen Frozen : Ledové království 2013 CD 31 633 Andrews, Troy Backatown 2010 CD 31 634 Andrews, Troy For true 2011 CD 31 635 Andrews, Troy Say that to say this 2013 CD 31 240 Anna K. -

Obligations, Sophisms and Insolubles∗

Obligations, Sophisms and Insolubles∗ Stephen Read University of St Andrews Scotland, U.K. March 23, 2012 1 Medieval Logic Medieval logic inherited the legacy of Aristotle: first, the logica vetus, Aristo- tle's Categories and De Interpretatione, which together with some of Boethius' works were all the logic the Latin West had to go on around 1100. Subse- quently, over the following century, came the recovery of the logica nova: the rest of Aristotle's Organon, all of which was available in Latin by 1200. The medievals' own original contribution began to be formulated from around 1150 and came to be known as the logica modernorum. It consisted of a theory of properties of terms (signification, supposition, appellation, ampli- ation, restriction etc.); a theory of consequences; a theory of insolubles; and a theory of obligations. This development was arguably stimulated by the theory of fallacy, following recovery of De Sophisticis Elenchis around 1140.1 It reached fulfilment in the 14th century, the most productive century for logic before the 20th. In this paper, I will concentrate for the most part on the theory of obligations|logical obligations. My focus will be on some logicians at the University of Oxford, mostly at Merton College, in the early fourteenth century, in particular, Walter Burley (or Burleigh), Richard Kilvington, Roger Swyneshed and William Heytesbury. I will contrast three different approaches to the theory of obli- gations found in these authors, and some of the reasons for these contrasts. The standard theory of obligations, the responsio antiqua, was codified by Burley in a treatise composed in Oxford in 1302. -

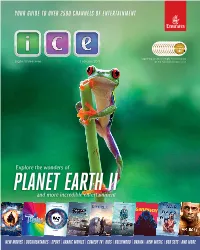

Your Guide to Over 2500 Channels of Entertainment

YOUR GUIDE TO OVER 2500 CHANNELS OF ENTERTAINMENT Voted World’s Best Infl ight Entertainment Digital Widescreen February 2017 for the 12th consecutive year! PLANET Explore the wonders ofEARTH II and more incredible entertainment NEW MOVIES | DOCUMENTARIES | SPORT | ARABIC MOVIES | COMEDY TV | KIDS | BOLLYWOOD | DRAMA | NEW MUSIC | BOX SETS | AND MORE ENTERTAINMENT An extraordinary experience... Wherever you’re going, whatever your mood, you’ll find over 2500 channels of the world’s best inflight entertainment to explore on today’s flight. 496 movies Information… Communication… Entertainment… THE LATEST MOVIES Track the progress of your Stay connected with in-seat* phone, Experience Emirates’ award- flight, keep up with news SMS and email, plus Wi-Fi and mobile winning selection of movies, you can’t miss and other useful features. roaming on select flights. TV, music and games. from page 16 STAY CONNECTED ...AT YOUR FINGERTIPS Connect to the OnAir Wi-Fi 4 103 network on all A380s and most Boeing 777s Move around 1 Choose a channel using the games Go straight to your chosen controller pad programme by typing the on your handset channel number into your and select using 2 3 handset, or use the onscreen the green game channel entry pad button 4 1 3 Swipe left and right like Search for movies, a tablet. Tap the arrows TV shows, music and ĒĬĩĦĦĭ onscreen to scroll system features ÊÉÏ 2 4 Create and access Tap Settings to Português, Español, Deutsch, 日本語, Français, ̷͚͑͘͘͏͐, Polski, 中文, your own playlist adjust volume and using Favourites brightness Many movies are available in up to eight languages. -

Logica Vetus in Medieval France Jacob Archambault

Contributions to a Codicological History of the Logica Vetus in Medieval France Jacob Archambault Abstract: In this paper, I provide a brief outline of shifts in the teaching of the texts of the Old Logic, or Logica Vetus, in France and its surrounding regions from the 10th to the mid-14th century, primarily relying on codicological evidence. The following shows: 1a) that prior to the 13th century, the teaching of the old logic was dominated by the reading of commentaries, primarily those of Boethius, and 1b) that during this same period, there are no clear signs of a systematic approach to teaching logic; 2) that during the 13th century, Boethius’ commentaries cease to be widely read, and the beginnings of a curriculum in logic develop; and 3) that the major development from the 13th to the 14th century in the organization of the Logica Vetus is the decreased presence of the Latin auctores, and a corresponding Hellenization of the study of logic more generally. Keywords: Aristoteles Latinus; Logic in Medieval France, history of; Ars Antiqua; Logica Vetus; Aristotle; Boethius; Medieval education, history of. Introduction This paper aims to outline the general features of the shift in the study of the Aristotelian logical corpus in the Gallican region from the 10th to the mid-14th century. The reason for this undertaking is in part a need to supplement more standard attempts at tracing the history of Medieval logic. Such accounts tend to be guided by, it seems to me, at least one of following three tendencies. The first is to focus heavily on the contributions of singular individuals, prodigies like Abelard or Ockham, who often attracted a number of followers.1 Though there certainly were major thinkers of this kind, the tendency to focus almost exclusively on them – trying, for instance, to determine whether one thinker is or is not directly acquainted with the thought of another – has arisen not so much because of the evidence itself as because of a certain romantic ideal governing much of our historiography of the middle ages, viz., that of the solitary genius. -

1 - Radio’S Place in the Media Landscape I

1 - Radio’s Place in the Media Landscape I ARBITRON: "RADIO LISTENING IS UP" 6-12-13 Arbitron released another RADAR National Radio Listening Report today. The report says radio’s audience increased year over year, adding more than 430,000 weekly listeners. Arbitron says radio now reaches 242.5 million listeners, or 92 percent of persons 12 and older, on an average weekly basis. Additionally, daily time spent listening to radio among persons age 12 and older held steady versus the June 2012 RADAR report. People 12 and older spend approximately 2 hours and 36 minutes a day with radio. Why Gen Y We can throw the 93% number around all we like, but the bottom line is that radio listening levels vary depending on the group you’re looking at. In a recent series of posts, we’ve talked about the concerning radio problem centering on lost youth – specifically, the notion that the medium has lost a generation of listeners over the past decade or so. Some might argue that we’re actually talking about two generations that are simply not as engaged with radio as their parents. Gen Y – or Millennials – is a case in point. Here’s their Media Usage Pyramid from Techsurvey9. A look at the black bar below indicates that 86% of these twenty and thirtysomethings listen to radio an hour a day or more. That’s below the study average of 89%. And this pattern intensifies when we examine Gen Z – those 20 and younger. Only 78% of them listen to broadcast radio for that one hour minimum a day. -

History of Medieval Philosophy

Syllabus 1 HISTORY OF MEDIEVAL PHILOSOPHY TIME: TTh 5:00-6:15 INSTRUCTOR: Stephen D. Dumont CONTACT: Malloy 301 /1-3757/ [email protected] OFFICE HOURS: By appointment. · REQUIRED TEXTS (Note edition) Hyman- Arthur Hyman and James J. Walsh, Philosophy in the Middle Ages 2nd ed. Walsh (Hackett , 1983) Spade Paul V. Spade, Five Texts on Mediaeval Problem of Universals (Hackett, 1994) Wolter Allan B. Wolter, Duns Scotus Philosophical Writings (Hackett, 1987) · RECOMMENDED TEXT McGrade Steven A. McGrade, Cambridge Companion to Medieval Philosophy (Cam- bridge, 2003) · COURSE REQUIREMENTS Undergraduate Graduate 25% = Midterm (Take-home) 50% = Research Term paper (20 pages) 25% = Term Paper (10 pages) 50% = Final (Take-home) 50% = Take Home Final · SYLLABUS: [Note: The following syllabus is ambitious and may be modified as we progress through the course. Many readings will be supplied or on deposit for you to copy.] EARLY MEDIEVAL PHILOSOPHY · BOETHIUS 1. Universals: Second Commentary on the Isagoge of Porphyry (In Isagogen Porphyrii commenta) [Handout from Richard McKeon, Selections from Medieval Philosophers. (New York, 1930), 1:70-99; cf. Spade, 20-25] 2. Divine Foreknowledge and Future Contingents: Consolation of Philosophy V [Handout from John F Wippel and Allan B. Wolter. Medieval Philosophy: From St. Augustine to Nicholas of Cusa, Readings in the History of Philosophy. (New York: Free Press), 1969, pp. 84-99] · ANSELM 1. Existence of God: Proslogion 1-4; On Behalf of the Fool by Gaunilo; Reply to the Fool. [Hyman-Walsh, 149-62] Syllabus 2 · ABELARD, 1. Universals: Glosses on Porphyry in Logic for Beginners (Logica ingredientibus) [Spade, 26-56; cf. -

History of Renaissance and Modern Logic from 1400 to 1850

History of Renaissance and Modern Logic from 1400 to 1850 https://www.historyoflogic.com/logic-modern.htm History of Logic from Aristotle to Gödel by Raul Corazzon | e-mail: [email protected] History of Renaissance and Modern Logic from 1400 to 1850 INTRODUCTION: LOGIC IN CONTINENTAL EUROPE "At the end of the fourteenth century there were roughly three categories of work available to those studying logic. The first category is that of commentaries on Aristotle's 'Organon'. The most comprehensive of these focussed either on the books of the Logica Vetus, which included Porphyry's Isagoge along with the Categories and De Interpretatione; or on the books of the Logica Nova, the remaining works of the 'Organon' which had become known to the West only during the twelfth century. In addition there were, of course, numerous commentaries on individual books of the 'Organon'. The second category is that of works on non-Aristotelian topics. These include the so-called Parva logicalia, or treatises on supposition, relative terms, ampliation, appellation, restriction and distribution. To these could be added tracts on exponibles and on syncategorematic terms. Peter of Spain is now the best-known author of parva logicalia, but such authors as Thomas Maulvelt and Marsilius of Inghen were almost as influential in the late fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. Another group of works belonging to the second category consists of the so-called 'tracts of the moderns', namely treatises on consequences, obligations and insolubles. A third group includes treatises on sophisms, on the composite and divided senses, and on proofs of terms, especially the well-known Speculum puerorum by Richard Billingham. -

Kenny Chesney and Darius Rucker to Appear at 2014 Honors Gala

For Immediate Release Contact: Luke Arterburn The Andrews Agency 615-242-4400 [email protected] Tinti Moffat T.J. Martell Foundation [email protected] Kenny Chesney and Darius Rucker to appear at 2014 Honors Gala Chesney and Rucker will pay tribute to Honorees: Mark Bloom, Beth Dortch Franklin, Scott Hiebert, Mike Dungan and Dale Morris NASHVILLE, Tenn. – January 3, 2014 – The T.J. Martell Foundation announced today two of the stars that are slated to make special appearances at the sixth annual Nashville Honors Gala. Country music recording artists Kenny Chesney and Darius Rucker will make special appearances at the gala, which will be held at the Nashville Omni Hotel on March 10, 2014. This year’s high profile affair will recogniZe individuals who have made significant contributions to the music industry, the Nashville economy and medical research. Honorees are Nashville real estate visionary Mark Bloom, music industry icons Dale Morris and Mike Dungan, entrepreneur Beth Dortch Franklin and cancer research pioneer Scott Hiebert. The T.J. Martell Foundation’s Nashville Honors Gala is a high-profile festive affair, which brings together celebrities with business, medical, sports and entertainment industry leaders to raise awareness and funds for innovative cancer research at 11 top research hospitals in the United States including the Frances Williams Preston Laboratories at the Vanderbilt-Ingram Cancer Center. “We are so excited that Kenny Chesney and Darius Rucker will be appearing to pay tribute to our honorees and to help support the wonderful work of the T.J. Martell Foundation,” said T.J. Martell’s Director of Strategic Development, Tinti Moffat. -

Top 40 UPDATE BILLBOARD.COM/NEWSLETTERS BILLBOARD.BIZ/NEWSLETTER JUNE 6, 2013 | PAGE 1 of 9

MID WEEK Top 40 UPDATE BILLBOARD.COM/NEWSLETTERS BILLBOARD.BIZ/NEWSLETTER JUNE 6, 2013 | PAGE 1 OF 9 INSIDE Top 40 And Radio Geeks, Unite! The Connected Consumer PAGE 3 RICH APPEL [email protected] What’s With a multitude of entertainment options out there, it’s easy to YOUNGER = HIGHER, LONGER, MORE New At forget that in top 40’s long history, a listener’s favorite station has Who are top 40’s P1s, and how engaged are they in the digital uni- The New never been the only game in town. There was always something verse? According to Edison Research VP Jason Hollins, 60% are Music else a consumer could do. Not to mention there are only so many female, 50% are age 12-24 and 60% 12-34, with an average age of hours in a day, right? 28. This younger skew means a greater Seminar The good news suggested by the HOW TOP 40’S P1s COMPARE TO THE POPULATION level of connectivity compared with PAGE 4 PERSONS TOP 40 Infinite Dial’s study of the format’s 12+ P1s not just other formats but to the 12- P1s—released last week by Edi- AM/FM radio usage in car 84% 88% plus and 12-34 population in general. Macklemore son Research and Arbitron—is that Awareness of Pandora 69% 88% Nearly 80% of P1s have Internet ac- & Ryan Lewis there seems to be plenty of room— Having a profile on any social network 62% 82% cess and use Wi-Fi, and one-third own and time—for all players.