HUSBANDRY GUIDELINES Eurasian Lynx

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Cost of Migratory Prey: Seasonal Changes in Semi-Domestic Reindeer Distribution Influences Breeding Success of Eurasian Lynx in Northern Norway

The cost of migratory prey: seasonal changes in semi-domestic reindeer distribution influences breeding success of Eurasian lynx in northern Norway Zea Walton1, Jenny Mattisson2, John D. C. Linnell2, Audun Stien3 and John Odden2 1Dept of Forestry and Wilderness Management, Hedmark College, Koppang, Norway 2Norwegian Inst. for Nature Research (NINA), NO-7484 Trondheim, Norway 3Norwegian Inst. for Nature Research (NINA), Fram Centre, Tromsø, Norway Corresponding author: Zea Walton, Dept of Forestry and Wilderness Management, Hedmark College, Koppang, Norway. E-mail: [email protected] Decision date: 31-Aug-2016 This article has been accepted for publication and undergone full peer review but has not been through the copyediting, typesetting, pagination and proofreading process, which may lead to differences between this version and the Version of Record. Please cite this article as doi: [10.1111/oik.03374]. ‘This article is protected by copyright. All rights reserved.’ Accepted Article Accepted (Abstract) Migratory prey is a widespread phenomenon that has implications for predator–prey interactions. By creating large temporal variation in resource availability between seasons it becomes challenging for carnivores to secure a regular year-round supply of food. Some predators may respond by following their migratory prey, however, most predators are sedentary and experience strong seasonal variation in resource availability. Increased predation on alternative prey may dampen such seasonal resource fluctuations, but reduced reproduction rates in predators is a predicted consequence of migratory primary prey behavior that has received little empirical attention. We used data from 23 GPS collared Eurasian lynx Lynx lynx monitored during 2007–2013 in northern Norway, to examine how spatio-temporal variation in the migratory behavior of semi-domestic reindeer Rangifer tarandus influences lynx spatial organization and reproductive success using estimates of seasonal home range overlap and breeding success. -

Wildlife; Threatened and Endangered Species

2009 SNF Monitoring and Evaluation Report Wildlife; Threatened and Endangered Species Introduction The data described in this report outlines the history, actions, procedures, and direction that the Superior National Forest (aka the Forest or SNF) has implemented in support of the Gray Wolf Recovery Plan and Lynx Conservation Assessment and Strategy (LCAS). The Forest contributes towards the conservation and recovery of the two federally listed threatened and endangered species: Canada lynx and gray wolf, through habitat and access management practices, collaboration with other federal and state agencies, as well as researchers, tribal bands and non-governmental partners. Canada lynx On 24 March 2000, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service designated the Canada lynx a “Threatened” species in the lower 48 states. From 2004-2009 the main sources of information about Canada lynx for the SNF included the following: • Since 2003 the Canada lynx study has been investigating key questions needed to contribute to the recovery and conservation of Canada lynx in the Western Great Lakes. Study methods are described in detail in the annual study progress report available online at the following address: http://www.nrri.umn.edu/lynx/ . These methods have included collecting information on distribution, snow tracking lynx, tracking on the ground and in the air radio-collared lynx, studying habitat use, collecting and analyzing genetic samples (for example, from hair or scat) and conducting pellet counts of snowshoe hare (the primary prey). • In 2006 permanent snow tracking routes were established across the Forest. The main objective is to maintain a standardized, repeatable survey to monitor lynx population indices and trends. -

Eurasian Lynx – Your Essential Brief

Eurasian lynx – Your essential brief Background Q: Are lynx native to Britain? A: Based on archaeological evidence, the range of the Eurasian lynx (Lynx lynx) included Britain until at least 1,300 years ago. It is difficult to be precise about when or why lynx became extinct here, but it was almost certainly related to human activity – deforestation removed their preferred habitat, and also that of their prey, thus reducing prey availability. These declines in prey species may have been exacerbated by human hunting. Q: Where do they live now? A: Across Europe, Scandinavia, Russia, northern China and Southeast Asia. The range used to include other areas of Western Europe, including Britain, where they are no longer present. Q: How many are there? A: There are thought to be around 50,000 in the world, of which 9,000 – 10,000 live in Europe. They are considered to be a species of least concern by the IUCN. Modern range of the Eurasian lynx Q: How big are they? A: Lynx are on average around 1m in length, 75cm tall and around 20kg, with the males being slightly larger than the females. They can live to 15 years old, but this is rare in the wild. Q: What do they eat? A: The preferred prey of the lynx are the smaller deer species, primarily the roe deer. Lynx may also prey upon other deer species, including chamois, sika deer, smaller red deer, muntjac and fallow deer. Q: Do they eat other things? A: Yes. Lynx prey on many other species when their preferred prey is scarce, including rabbits, hares, foxes, wildcats, squirrel, pine marten, domestic pets, sheep, goats and reared gamebirds. -

Status of Large Carnivores in Serbia

Status of large carnivores in Serbia Duško Ćirović Faculty of Biology University of Belgrade, Belgrade Status and threats of large carnivores in Serbia LC have differend distribution, status and population trends Gray wolf Eurasian Linx Brown Bear (Canis lupus) (Lynx lynx ) (Ursus arctos) Distribution of Brown Bear in Serbia Carpathian Dinaric-Pindos East Balkan Population status of Brown Bear in Serbia Dinaric-Pindos: Distribution 10000 km2 N=100-120 Population increase Range expansion Carpathian East Balkan: Distribution 1400 km2 Dinaric-Pindos N= a few East Balkan Population trend: unknown Carpathian: Distribution 8200 km2 N=8±2 Population stable Legal status of Brown Bear in Serbia According Law on Protection of Nature and the Law on Game and Hunting brown bear in Serbia is strictly protected species. He is under the centralized jurisdiction of the Ministry of Environmental Protection Treats of Brown Bear in Serbia Intensive forestry practice and infrastructure development . Illegal killing Low acceptance due to fear for personal safety Distribution of Gray wolf in Serbia Carpathian Dinaric-Pindos East Balkan Population status of Gray wolf in Serbia Dinaric-Balkan: 2 Carpathian Distribution cca 43500 km N=800-900 Population - stabile/slight increasingly Dinaric Range - slight expansion Carpathian: Distribution 480 km2 (was) Population – a few Population status of Gray wolf in Serbia Carpathian population is still undefined Carpathian Peri-Carpathian Legal status of Gray wolf in Serbia According the Law on Game and Hunting the gray wolf in majority pars of its distribution (south from Sava and Danube rivers) is game species with closing season from April 15th to July 1st. -

Black Bear Ecology Life Systems – Interactions Within Ecosystems a Guide for Grade 7 Teachers

BEAR WISE Black Bear Ecology Life Systems – Interactions Within Ecosystems A Guide for Grade 7 Teachers Ministry of Natural Resources BEAR WISE Introduction Welcome to Black Bear Ecology, Life Systems – Interactions Within Ecosystems, a Guide for Grade 7 Teachers. With a focus on the fascinating world of black bears, this program provides teachers with a classroom ready resource. Linked to the current Science and Technology curriculum (Life Systems strand), the Black Bear Ecology Guide for teachers includes: I background readings on habitats, ecosystems and the species within; food chains and food webs; ecosystem change; black bear habitat needs and ecology and bear-human interactions; I unit at a glance; I four lesson plans and suggested activities; I resources including a glossary; list of books and web sites and information sheets about black bears. At the back of this booklet, you will find a compact disk. It includes in Portable Document Format (PDF) the English and French versions of this Grade 7 unit; the Grades 2 and 4 units; the information sheets and the Are You Bear Wise? eBook (2005). This program aims to generate awareness about black bears – their biological needs; their behaviour and how human action influences bears. It is an initiative of the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources. BEAR WISE Acknowledgements The Ministry of Natural Resources would like to thank the following people for their help in developing the Black Bear Ecology Education Program. This education program would not have been possible without their contributions -

Wildlife Research Reports

MAMMALS - JULY 2005 WILDLIFE RESEARCH REPORTS JULY 2004 – JUNE 2005 MAMMALS PROGRAM COLORADO DIVISION OF WILDLIFE Research Center, 317 W. Prospect, Fort Collins, CO 80526 The Wildlife Reports contained herein represent preliminary analyses and are subject to change. For this reason, information MAY NOT BE PUBLISHED OR QUOTED without permission of the Author. STATE OF COLORADO Bill Owens, Governor DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES Russell George, Executive Director WILDLIFE COMMISSION Jeffrey Crawford, Chair …………………………………………………………………….…..… Denver Tom Burke, Vice Chair ………………………………….…………...………….…........…Grand Junction Ken Torres, Secretary ……………………………………...…………….……………..……….... Weston Robert Bray………………………………………………….......................................................…Redvale Rick Enstrom………………………………………………………………….………….……...Lakewood Philip James …………………………………………………………………..….………….…Fort Collins Claire M. O’Neal………………………………………………..…………….………..…………..Holyoke Richard Ray ………………………………………………………………………………...Pagosa Springs Robert T. Shoemaker…………………………………………………………….………..…….Canon City Don Ament, Dept. of Ag, Ex-officio…………………………………………………….…….....Lakewood Russell George, Executive Director, Ex-officio……………………………………………..………Denver DIRECTOR’S STAFF Bruce McCloskey, Director Mark Konishi, Deputy Director-Education and Public Affairs Steve Cassin, Chief Financial Officer Jeff Ver Steeg, Assistant Director-Wildlife Programs John Bredehoft, Assistant Director-Field Operations Marilyn Salazar, Assistant Director-Support Services MAMMALS RESEARCH STAFF David Freddy, -

Prey Density, Environmental Productivity and Home-Range Size in the Eurasian Lynx (Lynx Lynx)

J. Zool., Lond. (2005) 265, 63–71 C 2005 The Zoological Society of London Printed in the United Kingdom DOI:10.1017/S0952836904006053 Prey density, environmental productivity and home-range size in the Eurasian lynx (Lynx lynx) Ivar Herfindal1, John D. C. Linnell2*, John Odden2, Erlend Birkeland Nilsen1 and Reidar Andersen1,2 1 Department of Biology, Norwegian University of Science and Technology, N-7491 Trondheim, Norway 2 Norwegian Institute for Nature Research, Tungasletta 2, N-7485 Trondheim, Norway (Accepted 19 May 2004) Abstract Variation in size of home range is among the most important parameters required for effective conservation and management of a species. However, the fact that home ranges can vary widely within a species makes data transfer between study areas difficult. Home ranges of Eurasian lynx Lynx lynx vary by a factor of 10 between different study areas in Europe. This study aims to try and explain this variation in terms of readily available indices of prey density and environmental productivity. On an individual scale we related the sizes of 52 home ranges, derived from 23 (9:14 male:female) individual resident lynx obtained from south-eastern Norway, with an index of density of roe deer Capreolus capreolus. This index was obtained from the density of harvested roe deer within the municipalities covered by the lynx home ranges. We found a significant negative relationship between harvest density and home- range size for both sexes. On a European level we related the sizes of 111 lynx (48:63 male: female) from 10 study sites to estimates derived from remote sensing of environmental productivity and seasonality. -

Lynx, Felis Lynx, Predation on Red Foxes, Vulpes Vulpes, Caribou

Lynx, Fe/is lynx, predation on Red Foxes, Vulpes vulpes, Caribou, Rangifer tarandus, and Dall Sheep, Ovis dalli, in Alaska ROBERT 0. STEPHENSON, 1 DANIEL V. GRANGAARD,2 and JOHN BURCH3 1Alaska Department of Fish and Game, 1300 College Road, Fairbanks, Alaska, 99701 2Alaska Department of Fish and Game, P.O. Box 305, Tok, Alaska 99780 JNational Park Service, P.O. Box 9, Denali National Park, Alaska 99755 Stephenson, Robert 0., Daniel Y. Grangaard, and John Burch. 1991. Lynx, Fe/is lynx, predation on Red Foxes, Vulpes vulpes, Caribou, Rangifer tarandus, and Dall Sheep, Ovis dalli, in Alaska. Canadian Field-Naturalist 105(2): 255- 262. Observations of Canada Lynx (Fe/is lynx) predation on Red Foxes ( Vulpes vulpes) and medium-sized ungulates during winter are reviewed. Characteristics of I 3 successful attacks on Red Foxes and 16 cases of predation on Caribou (Rangifer tarandus) and Dall Sheep (Ovis dalli) suggest that Lynx are capable of killing even adults of these species, with foxes being killed most easily. The occurrence of Lynx predation on these relatively large prey appears to be greatest when Snowshoe Hares (Lepus americanus) are scarce. Key Words: Canada Lynx, Fe/is lynx, Red Fox, Vulpes vulpes, Caribou, Rangifer tarandus, Dall Sheep, Ovis dalli, predation, Alaska. Although the European Lynx (Felis lynx lynx) quently reach 25° C in summer and -10 to -40° C in regularly kills large prey (Haglund 1966; Pullianen winter. Snow depths are generally below 80 cm, 1981), the Canada Lynx (Felis lynx canadensis) and snow usually remains loosely packed except at relies largely on small game, primarily Snowshoe high elevations. -

Current Status of the Eurasian Lynx. Cat News. (2016)

ISSN 1027-2992 I Special Issue I N° 10 | Autumn 2016 CatsCAT in Iran news 02 CATnews is the newsletter of the Cat Specialist Group, a component Editors: Christine & Urs Breitenmoser of the Species Survival Commission SSC of the International Union Co-chairs IUCN/SSC for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). It is published twice a year, and is Cat Specialist Group available to members and the Friends of the Cat Group. KORA, Thunstrasse 31, 3074 Muri, Switzerland For joining the Friends of the Cat Group please contact Tel ++41(31) 951 90 20 Christine Breitenmoser at [email protected] Fax ++41(31) 951 90 40 <[email protected]> Original contributions and short notes about wild cats are welcome Send <[email protected]> contributions and observations to [email protected]. Guidelines for authors are available at www.catsg.org/catnews Cover Photo: From top left to bottom right: Caspian tiger (K. Rudloff) This Special Issue of CATnews has been produced with support Asiatic lion (P. Meier) from the Wild Cat Club and Zoo Leipzig. Asiatic cheetah (ICS/DoE/CACP/ Panthera) Design: barbara surber, werk’sdesign gmbh caracal (M. Eslami Dehkordi) Layout: Christine Breitenmoser & Tabea Lanz Eurasian lynx (F. Heidari) Print: Stämpfli Publikationen AG, Bern, Switzerland Pallas’s cat (F. Esfandiari) Persian leopard (S. B. Mousavi) ISSN 1027-2992 © IUCN/SSC Cat Specialist Group Asiatic wildcat (S. B. Mousavi) sand cat (M. R. Besmeli) jungle cat (B. Farahanchi) The designation of the geographical entities in this publication, and the representation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the IUCN concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. -

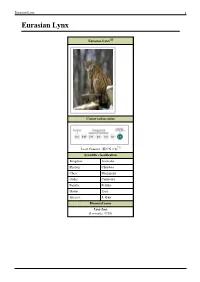

Eurasian Lynx 1 Eurasian Lynx

Eurasian Lynx 1 Eurasian Lynx Eurasian Lynx[1] Conservation status [2] Least Concern (IUCN 3.1) Scientific classification Kingdom: Animalia Phylum: Chordata Class: Mammalia Order: Carnivora Family: Felidae Genus: Lynx Species: L. lynx Binomial name Lynx lynx (Linnaeus, 1758) Eurasian Lynx 2 Eurasian Lynx range Synonyms Felis lynx (Linnaeus, 1758) The Eurasian lynx (Lynx lynx) is a medium-sized cat native to European and Siberian forests, South Asia and East Asia. It is also known as the European lynx, common lynx, the northern lynx, and the Siberian or Russian lynx. While its conservation status has been classified as "Least Concern", populations of Eurasian lynx have been reduced or extirpated from western Europe, where it is now being reintroduced. Physical characteristics The Eurasian lynx is the largest lynx species, ranging in length from 80 to 130 cm (31 to 51 in) and standing about 70 cm (28 in) at the shoulder. The tail measures 11 to 25 cm (4.3 to 9.8 in) in length. Males usually weigh from 18 to 30 kg (40 to 66 lb) and females weigh 10 to 21 kg (22 to 46 lb).[3] [4] [5] Male lynxes from Siberia, where the species reaches the largest body size, can weigh up to 38 kg (84 lb) or reportedly even 45 kg (99 lb).[6] [7] It has powerful legs, with large webbed and furred paws that act like snowshoes. It also possesses a short "bobbed" tail with an all-black tip, black tufts of hair on its ears, and a long grey-and-white ruff. -

Revealed Via Genomic Assessment of Felid Cansines

Evolutionary and Functional Impacts of Short Interspersed Nuclear Elements (SINEs) Revealed via Genomic Assessment of Felid CanSINEs By Kathryn B. Walters-Conte B. S., May 2000, University of Maryland, College Park M. S., May 2002, The George Washington University A Dissertation Submitted to The Faculty of Columbian College of Arts and Sciences of The George Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 15 th , 2011 Dissertation Directed By Diana L.E. Johnson Associate Professor of Biology Jill Pecon-Slattery Staff Scientist, National Cancer Institute . The Columbian College of Arts and Sciences of The George Washington University certifies that Kathryn Walters-Conte has passed the Final Examination for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy as of March 24 th , 2011. This is the final and approved form of the dissertation. Evolutionary and Functional Impacts of Short Interspersed Nuclear Elements (SINEs) Revealed via Genomic Assessment of Felid CanSINEs Kathryn Walters-Conte Dissertation Research Committee: Diana L.E. Johnson, Associate Professor of Biology, Dissertation Co-Director Jill Pecon-Slattery, Staff Scientist, National Cancer Institute, Dissertation Co-Director Diana Lipscomb, Ronald Weintraub Chair and Professor, Committee Member Marc W. Allard, Research Microbiologist, U.S. Food and Drug Administration, Committee Member ii Acknowledgements I would like to first thank my advisor and collaborator, Dr. Jill Pecon-Slattery, at the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health, for generously permitting me to join her research group. Without her mentorship this dissertation would never have been possible. I would also like to express gratitude to my advisor at the George Washington University, Dr. -

The IUCN Red List of Threatened Speciestm

Species 2014 Annual ReportSpecies the Species of 2014 Survival Commission and the Global Species Programme Species ISSUE 56 2014 Annual Report of the Species Survival Commission and the Global Species Programme • 2014 Spotlight on High-level Interventions IUCN SSC • IUCN Red List at 50 • Specialist Group Reports Ethiopian Wolf (Canis simensis), Endangered. © Martin Harvey Muhammad Yazid Muhammad © Amazing Species: Bleeding Toad The Bleeding Toad, Leptophryne cruentata, is listed as Critically Endangered on The IUCN Red List of Threatened SpeciesTM. It is endemic to West Java, Indonesia, specifically around Mount Gede, Mount Pangaro and south of Sukabumi. The Bleeding Toad’s scientific name, cruentata, is from the Latin word meaning “bleeding” because of the frog’s overall reddish-purple appearance and blood-red and yellow marbling on its back. Geographical range The population declined drastically after the eruption of Mount Galunggung in 1987. It is Knowledge believed that other declining factors may be habitat alteration, loss, and fragmentation. Experts Although the lethal chytrid fungus, responsible for devastating declines (and possible Get Involved extinctions) in amphibian populations globally, has not been recorded in this area, the sudden decline in a creekside population is reminiscent of declines in similar amphibian species due to the presence of this pathogen. Only one individual Bleeding Toad was sighted from 1990 to 2003. Part of the range of Bleeding Toad is located in Gunung Gede Pangrango National Park. Future conservation actions should include population surveys and possible captive breeding plans. The production of the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species™ is made possible through the IUCN Red List Partnership.