Grasslands Ecosystems, Endangered Species, and Sustainable Ranching

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wilderness Visitors and Recreation Impacts: Baseline Data Available for Twentieth Century Conditions

United States Department of Agriculture Wilderness Visitors and Forest Service Recreation Impacts: Baseline Rocky Mountain Research Station Data Available for Twentieth General Technical Report RMRS-GTR-117 Century Conditions September 2003 David N. Cole Vita Wright Abstract __________________________________________ Cole, David N.; Wright, Vita. 2003. Wilderness visitors and recreation impacts: baseline data available for twentieth century conditions. Gen. Tech. Rep. RMRS-GTR-117. Ogden, UT: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. 52 p. This report provides an assessment and compilation of recreation-related monitoring data sources across the National Wilderness Preservation System (NWPS). Telephone interviews with managers of all units of the NWPS and a literature search were conducted to locate studies that provide campsite impact data, trail impact data, and information about visitor characteristics. Of the 628 wildernesses that comprised the NWPS in January 2000, 51 percent had baseline campsite data, 9 percent had trail condition data and 24 percent had data on visitor characteristics. Wildernesses managed by the Forest Service and National Park Service were much more likely to have data than wildernesses managed by the Bureau of Land Management and Fish and Wildlife Service. Both unpublished data collected by the management agencies and data published in reports are included. Extensive appendices provide detailed information about available data for every study that we located. These have been organized by wilderness so that it is easy to locate all the information available for each wilderness in the NWPS. Keywords: campsite condition, monitoring, National Wilderness Preservation System, trail condition, visitor characteristics The Authors _______________________________________ David N. -

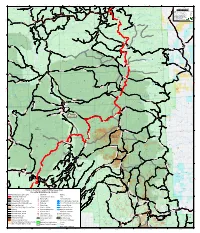

Trails in the Aldo Leopold Wilderness Area Recently Maintained & Cleared

l y R. 13 W. R. 12 W. R. 11 W. r l R. 10 W. t R. 9 W. R. 8 W. i r e t e 108°0'W m 107°45'W a v w o W a P S S le 11 Sawmill t Boundary Tank F t 6 40 10 i 1 6 Peak L 5 6 7M 10 11 9 1:63,360 0 0 8 9 12 8 8350 anyon Houghton Spring 4 7 40 7 5 7 T e C 1 in = 1 miles 11 12 4 71 7 7 0 Klin e C 10 0 C H 6 0 7 in Water anyon 8 9 6 a 4 0 Ranch P 4065A 7 Do 6 n 4 073Q (printed on 36" x 42" portrait layout) Houghton ag Z y 4 Well 12 Corduroy Corral y Doagy o 66 11 n 5 aska 10 Spr. Spr. Tank K Al 0 0.25 0.5 1 1.5 2 9 Corduroy Tank 1 1 14 13 7 2 15 5 0 4 Miles 5 Doagie Spr. 5 16 9 Beechnut Tank 4 0 17 6 13 18 n 8 14 yo 1 15 an Q C Deadman Tank 16 D Coordinate System: NAD 1983 UTM Zone 12NTransverse Mercator 3 3 3 17 0 r C 2 Sawmill 1 0 Rock 7 18 a Alamosa 13 w 6 1 Spr. Core 14 Attention: Reilly 6 Dirt Tank 8 15 0 Peak 14 Dev. Tank 3 Clay 4 15 59 16 Gila National Forest uses the most current n 0 16 S o 17 13 Santana 8163 1 17 3 y Doubleheader #2 Tank 18 Fence Tank Cr. -

Journal of Wilderness

INTERNATIONAL Journal of Wilderness DECEMBER 2005 VOLUME 11, NUMBER 3 FEATURES SCIENCE AND RESEARCH 3 Is Eastern Wilderness ”Real”? PERSPECTIVES FROM THE ALDO LEOPOLD WILDERNESS RESEARCH INSTITUTE BY REBECCA ORESKES 30 Social and Institutional Influences on SOUL OF THE WILDERNESS Wilderness Fire Stewardship 4 Florida Wilderness BY KATIE KNOTEK Working with Traditional Tools after a Hurricane BY SUSAN JENKINS 31 Wilderness In Whose Backyard? BY GARY T. GREEN, MICHAEL A. TARRANT, UTTIYO STEWARDSHIP RAYCHAUDHURI, and YANGJIAN ZHANG 7 A Truly National Wilderness Preservation System BY DOUGLAS W. SCOTT EDUCATION AND COMMUNICATION 39 Changes in the Aftermath of Natural Disasters 13 Keeping the Wild in Wilderness When Is Too Much Change Unacceptable to Visitors? Minimizing Nonconforming Uses in the National Wilderness Preservation System BY JOSEPH FLOOD and CRAIG COLISTRA BY GEORGE NICKAS and KEVIN PROESCHOLDT 19 Developing Wilderness Indicators on the INTERNATIONAL PERSPECTIVES White Mountain National Forest 42 Wilderness Conservation in a Biodiversity Hotspot BY DAVE NEELY BY RUSSELL A. MITTERMEIER, FRANK HAWKINS, SERGE RAJAOBELINA, and OLIVIER LANGRAND 22 Understanding the Cultural, Existence, and Bequest Values of Wilderness BY RUDY M. SCHUSTER, H. KEN CORDELL, and WILDERNESS DIGEST BRAD PHILLIPS 46 Announcements and Wilderness Calendar 26 8th World Wilderness Congress Generates Book Review Conservation Results 48 How Should America’s Wilderness Be Managed? BY VANCE G. MARTIN edited by Stuart A. Kallen REVIEWED BY JOHN SHULTIS FRONT COVER The magnificent El Carmen escaprment, one of the the “sky islands” of Coahuilo, Mexico. Photo by Patricio Robles Gil/Sierra Madre. INSET Ancient grain grinding site, Maderas del Carmen, Coahuilo, Mexico. Photo by Vance G. -

Fiscal Impact Reports (Firs) Are Prepared by the Legislative Finance Committee (LFC) for Standing Finance Committees of the NM Legislature

Fiscal impact reports (FIRs) are prepared by the Legislative Finance Committee (LFC) for standing finance committees of the NM Legislature. The LFC does not assume responsibility for the accuracy of these reports if they are used for other purposes. Current FIRs (in HTML & Adobe PDF formats) are available on the NM Legislative Website (www.nmlegis.gov). Adobe PDF versions include all attachments, whereas HTML versions may not. Previously issued FIRs and attachments may be obtained from the LFC in Suite 101 of the State Capitol Building North. F I S C A L I M P A C T R E P O R T ORIGINAL DATE 02/07/13 SPONSOR Herrell/Martinez LAST UPDATED 02/18/13 HB 292 SHORT TITLE Transfer of Public Land Act SB ANALYST Weber REVENUE (dollars in thousands) Recurring Estimated Revenue Fund or Affected FY13 FY14 FY15 Nonrecurring (See Narrative) There (See Narrative) There may be additional may be additional Recurring General Fund revenue in future years. revenue in future years. (Parenthesis ( ) Indicate Revenue Decrease ESTIMATED ADDITIONAL OPERATING BUDGET IMPACT (dollars in thousands) 3 Year Recurring or Fund FY13 FY14 FY15 Total Cost Nonrecurring Affected General Total $100.0 $100.0 $200.0 Recurring Fund (Parenthesis ( ) Indicate Expenditure Decreases) Duplicate to SB 404 SOURCES OF INFORMATION LFC Files Responses Received From Administrative Office of the Courts (AOC) General Services Department (GSD) Economic Development Department (EDD) Department of Cultural Affairs (DCA) Energy, Minerals and Natural Resources Department (EMNRD) State Land Office (SLO) Department of Transportation (DOT) Department of Finance and Administration (DFA) House Bill 292 – Page 2 SUMMARY Synopsis of Bill House Bill 292 (HB 292) is the Transfer of Public Lands Act. -

A Path Through the Wilderness: the Story of Forest Road

A Path Through the Wilderness: The Story of Forest Road 150 Gila National Forest Erin Knolles Assistant Forest Archeologist March 2016 1 National Forest System Road 150 [commonly referred to as Forest Road (FR) 150], begins within the confines of the Gila National Forest and stretches north about 55 miles from NM 35 near Mimbres past Beaverhead Work Center to NM 163 north of the Gila National Forest boundary. FR 150 is the main road accessing this area of the Gila National Forest. Its location between two Wilderness Areas, Aldo Leopold and the Gila, makes it an important corridor for public access, as well as, administrative access for the Gila National Forest. Forest Road 150: The Name and a Brief History FR150 has been known by several names. The road was first called the North Star Road by the residents of Grant County and the U.S. Military when it was constructed in the 1870s.1 Today, the route is still called the North Star Road and used interchangeably with FR 150. Through most of the 20th century, FR 150 was under New Mexico state jurisdiction and named New Mexico (NM) 61.2 Of interest is that topographical maps dating to at least 1980, list the road as both NM 61 and FR 150.3 This is interesting because, today, it is common practice not to give roads Forest Service names unless they are under the jurisdiction of the Forest Service. In addition, the 1974 Gila National Forest Map refers to the route as FR 150.4 There is still some question when the North Star Road and NM 61 became known as FR 150. -

Jaguar Critical Habitat Comments in Response to 71 FR 50214-50242 (Aug

October 19, 2012 Submitted on-line via www.regulations.gov, Docket No. FWS-R2-ES-2012-0042. Re: Jaguar critical habitat comments in response to 71 FR 50214-50242 (Aug. 20, 2012). To Whom it May Concern, The Center for Biological Diversity supports the designation of the entirety of the areas that the Fish and Wildlife Service proposes as critical habitat. However, these areas are not sufficient to conserve the jaguar in the United States. Nor does the Service’s itemization of threats to critical habitat areas cover the array of actions that would in fact destroy or adversely modify them. As we explain in detail in the comments below and through evidence presented in our appended letter of 10/1/2012 on the Recovery Outline for the Jaguar, we request seven principal changes in the final critical habitat designation rule, as follows: 1. The following additional mountain ranges within the current boundary of the Northwestern Recovery Unit (as described in the April 2012 Recovery Outline for the Jaguar) should be designated as critical habitat: in Arizona, the Chiricahua, Dos Cabezas, Dragoon and Mule mountains, and in New Mexico the Animas and adjoining Pyramid mountains. 2. The following additional “sky island” mountain ranges outside of the current boundaries of the Northwestern Recovery Unit should be designated as critical habitat: In New Mexico, the Alama Hueco, Big Hatchet, Little Hatchet, Florida, West and East Potrillo, Cedar and Big Burro mountains; in Arizona, the Galiuro, Santa Teresa, Pinaleno, Whitlock, Santa Catalina and Rincon mountains. Straddling both states, the Peloncillo Mountains north of the current boundaries of the Northwestern Recovery Unit should also be designated 3. -

Trails in the Aldo Leopold Wilderness Area C

l y R. 13 W. R. 12 W. R. 11 W. r l R. 10 W. t R. 9 W. R. 8 W. i r e t e 108°0'W m 107°45'W a v w o W a P S 4 S le 0 11 Sawmill t 6 t F 7 10 i 150 6 66Z M 3 Peak L 1:63,360 6 40 10 11 0 9 Boundary 0 8 9 12 1 8 8350 4 4 Canyon 7 0 7 8 T 1 in = 1 miles Spring 11 12 71 70 Kline C Tank 10 C H 677 anyon 9 a 4075 0 Ranch Pine 4065A 7 8 Corduroy Doagy n 4 73Q (printed on 36" x 42" portrait layout) Houghton y 40 12 o 665 Doagy n a 11 Tank 7 lask 0 0.25 0.5 1 1.5 2 10 Spr. Tank K 1 A 13 9 Houghton Corduroy Corral Spr. 1 0 14 5 Beechnut 7 3 15 Miles 95 Doagie Spr. 0 521 4 16 Water Well Deadman Tank 4 0 18 17 6 14 13 yon Tank 8 15 an Q C Draw Coordinate System: NAD 1983 UTM Zone 12NTransverse Mercator 17 16 C 13 18 6 14 Attention: Reilly 6 231 Doagy Sawmill 15 0 14 Fence Peak Clay 4 15 59 16 Gila National Forest uses the most current n Alamosa Tank 16 13 Spr. Dev. Tank 8163 o 17 Rock Core S Santana Grafton y 18 17 r. Tank 3 n Doubleheader #2 Slash 14 13 Dirt Tank 18 y C and complete data available. -

94 Stat. 3228 Public Law 96-550—Dec

PUBLIC LAW 96-550—DEC. 19, 1980 94 STAT. 3221 Public Law 96-550 96th Congress An Act To designate certein National Forest System lands in the State of New Mexico for Dec. 19, 1980 inclusion in the National Wilderness Preservation System, and for other [H.R. 8298] purposes. Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled, National Forest System lands, N. Mex. TITLE I Designation. SEC. 101. The purposes of this Act are to— (1) designate certain National Forest System lands in New Mexico for inclusion in the National Wilderness Preservation System in order to promote, perpetuate, and preserve the wilder ness character of the land, to protect watersheds and wildlife habitat, preserve scenic and historic resources, and to promote scientific research, primitive recreation, solitude, physical and mental challenge, and inspiration for the benefit of all the American people; (2) insure that certain other National Forest System lands in New Mexico be promptly available for nonwilderness uses including, but not limited to, campground and other recreation site development, timber harvesting, intensive range manage ment, mineral development, and watershed and vegetation manipulation; and (3) designate certain other National Forest System land in New Mexico for further study in furtherance of the purposes of the Wilderness Act. 16 use 1131 SEC. 102. (a) In furtherance of the purposes of the Wilderness Act, note. the following National Forest System lands in the State of New Mexico are hereby designated as wilderness, and therefore, as compo nents of the National Wilderness Preservation System— (1) certain lands in the Gila National Forest, New Mexico, 16 use 1132 which comprise approximately two hundred and eleven thou note. -

Montana, and the Gila/Aldo Leopold Wilderness Complex, New Mexico

Twentieth-Century Fire Patterns in the Selway-Bitterroot Wilderness Area, Idaho/ Montana, and the Gila/Aldo Leopold Wilderness Complex, New Mexico Matthew Rollins Tom Swetnam Penelope Morgan Abstract—Twentieth century fire patterns were analyzed for two The objectives of our research were to characterize the large, disparate wilderness areas in the Rocky Mountains. Spatial interrelationships among fire, topography, and vegetation and temporal patterns of fires were represented as GIS-based across two major Rocky Mountain Wilderness ecosystems: digital fire atlases compiled from archival Forest Service data. We the Selway-Bitterroot Wilderness Area in Idaho and Mon- find that spatial and temporal fire patterns are related to landscape tana and the Gila/Aldo Leopold Wilderness Complex in New features and changes in land use. The rate and extent of burning are Mexico. Comparing results between two distinct regions, the interpreted in the context of changing fire management strategies northern and southern Rocky Mountains, provides a re- in each wilderness area. This research provides contextual informa- gional perspective. Fire-climate relationships may be stud- tion to guide fire management in these (and similar) areas in the ied at these scales. Differences and similarities in our results future and forms the basis for future research involving the empiri- enable us to determine whether fire-landscape relationships cal definition of fire regimes based on spatially explicit time-series are determined by constraints at local or regional scales. of fire occurrence. This paper describes the acquisition and compilation of GIS databases for each wilderness area, a graphical analysis of spatial and temporal fire patterns, and a comparison of patterns found in each wilderness. -

Wilderness Ecosystems, Threats, and Management; 1999 May 23– Lasiocarpa) (Var

Twentieth-Century Fire Patterns in the Selway-Bitterroot Wilderness Area, Idaho/ Montana, and the Gila/Aldo Leopold Wilderness Complex, New Mexico Matthew Rollins Tom Swetnam Penelope Morgan Abstract—Twentieth century fire patterns were analyzed for two The objectives of our research were to characterize the large, disparate wilderness areas in the Rocky Mountains. Spatial interrelationships among fire, topography, and vegetation and temporal patterns of fires were represented as GIS-based across two major Rocky Mountain Wilderness ecosystems: digital fire atlases compiled from archival Forest Service data. We the Selway-Bitterroot Wilderness Area in Idaho and Mon- find that spatial and temporal fire patterns are related to landscape tana and the Gila/Aldo Leopold Wilderness Complex in New features and changes in land use. The rate and extent of burning are Mexico. Comparing results between two distinct regions, the interpreted in the context of changing fire management strategies northern and southern Rocky Mountains, provides a re- in each wilderness area. This research provides contextual informa- gional perspective. Fire-climate relationships may be stud- tion to guide fire management in these (and similar) areas in the ied at these scales. Differences and similarities in our results future and forms the basis for future research involving the empiri- enable us to determine whether fire-landscape relationships cal definition of fire regimes based on spatially explicit time-series are determined by constraints at local or regional scales. of fire occurrence. This paper describes the acquisition and compilation of GIS databases for each wilderness area, a graphical analysis of spatial and temporal fire patterns, and a comparison of patterns found in each wilderness. -

Preliminary Draft Land Management Plan for the Gila National Forest Catron, Grant, Hidalgo, and Sierra Counties, New Mexico

United States Department of Agriculture Preliminary Draft Land Management Plan for the Gila National Forest Catron, Grant, Hidalgo, and Sierra Counties, New Mexico U.S. Forest Service Southwestern Region March 2018 Cover Photo: Woodland Park In accordance with Federal civil rights law and U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) civil rights regulations and policies, the USDA, its Agencies, offices, and employees, and institutions participating in or administering USDA programs are prohibited from discriminating based on race, color, national origin, religion, sex, gender identity (including gender expression), sexual orientation, disability, age, marital status, family/parental status, income derived from a public assistance program, political beliefs, or reprisal or retaliation for prior civil rights activity, in any program or activity conducted or funded by USDA (not all bases apply to all programs). Remedies and complaint filing deadlines vary by program or incident. Persons with disabilities who require alternative means of communication for program information (e.g., Braille, large print, audiotape, American Sign Language, etc.) should contact the responsible Agency or USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TTY) or contact USDA through the Federal Relay Service at (800) 877-8339. Additionally, program information may be made available in languages other than English. To file a program discrimination complaint, complete the USDA Program Discrimination Complaint Form, AD-3027, found online at http://www.ascr.usda.gov/complaint_filing_cust.html and at any USDA office or write a letter addressed to USDA and provide in the letter all of the information requested in the form. To request a copy of the complaint form, call (866) 632-9992. -

The Gila Example

2012 Wilderness Designation and Livestock Grazing: The Gila Example RITF Report 83 Nick Ashcroft Extension Range Management Specialist Cooperative Extension Service John M. Fowler Chair/Director, Linebery Policy Center Agricultural Experiment Station Sylvia Beuhler, Student Dawn VanLeeuwen, Professor Wilderness Designation and Livestock Grazing: The Gila Example Nick Ashcroft, John M. Fowler, Sylvia Beuhler, and Dawn VanLeeuwen1 INTRODUCTION Wilderness negatively impacts local economic The concept of a “wilderness” can stir conditions....the Wilderness designation is conflicting emotions, from wonder at the significantly associated with lower per capita tranquility and untrammeled beauty to income, lower total payroll, and lower tax the terror of a wild, untamed environment receipts in counties” (pp. 1, 3). where Mother Nature acts via spectacular The uncertainty of economic impacts and uncontrolled events. There are many stretches from local economies down views between these two extremes, and each to individual ranch units’ profitability. view is based on the individual’s intrinsic Alternative viewpoints range from adverse value system. impacts due to increased restrictions and The potential impacts on local high opportunity costs because of the economies due to wilderness designation are wilderness designation to positive impacts equally uncertain. The Sonoran Institute due to enhanced property values and in 2006 concluded “that protecting a increased local tourism revenues. This portion of [Doña Ana County, NM’s] paper examines the actual changes—due public lands as Wilderness (and a related to wilderness designation—in livestock National Conservation Area) is likely to numbers on an animal unit month per acre have positive effects on future prosperity— (AUM/acre)2 basis in the Gila Wilderness, and that the more public lands afforded the oldest wilderness area in the United these protections the better for the area States.