Journal of Wilderness

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wilderness Visitors and Recreation Impacts: Baseline Data Available for Twentieth Century Conditions

United States Department of Agriculture Wilderness Visitors and Forest Service Recreation Impacts: Baseline Rocky Mountain Research Station Data Available for Twentieth General Technical Report RMRS-GTR-117 Century Conditions September 2003 David N. Cole Vita Wright Abstract __________________________________________ Cole, David N.; Wright, Vita. 2003. Wilderness visitors and recreation impacts: baseline data available for twentieth century conditions. Gen. Tech. Rep. RMRS-GTR-117. Ogden, UT: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. 52 p. This report provides an assessment and compilation of recreation-related monitoring data sources across the National Wilderness Preservation System (NWPS). Telephone interviews with managers of all units of the NWPS and a literature search were conducted to locate studies that provide campsite impact data, trail impact data, and information about visitor characteristics. Of the 628 wildernesses that comprised the NWPS in January 2000, 51 percent had baseline campsite data, 9 percent had trail condition data and 24 percent had data on visitor characteristics. Wildernesses managed by the Forest Service and National Park Service were much more likely to have data than wildernesses managed by the Bureau of Land Management and Fish and Wildlife Service. Both unpublished data collected by the management agencies and data published in reports are included. Extensive appendices provide detailed information about available data for every study that we located. These have been organized by wilderness so that it is easy to locate all the information available for each wilderness in the NWPS. Keywords: campsite condition, monitoring, National Wilderness Preservation System, trail condition, visitor characteristics The Authors _______________________________________ David N. -

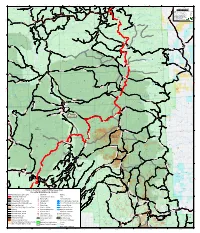

Trails in the Aldo Leopold Wilderness Area Recently Maintained & Cleared

l y R. 13 W. R. 12 W. R. 11 W. r l R. 10 W. t R. 9 W. R. 8 W. i r e t e 108°0'W m 107°45'W a v w o W a P S S le 11 Sawmill t Boundary Tank F t 6 40 10 i 1 6 Peak L 5 6 7M 10 11 9 1:63,360 0 0 8 9 12 8 8350 anyon Houghton Spring 4 7 40 7 5 7 T e C 1 in = 1 miles 11 12 4 71 7 7 0 Klin e C 10 0 C H 6 0 7 in Water anyon 8 9 6 a 4 0 Ranch P 4065A 7 Do 6 n 4 073Q (printed on 36" x 42" portrait layout) Houghton ag Z y 4 Well 12 Corduroy Corral y Doagy o 66 11 n 5 aska 10 Spr. Spr. Tank K Al 0 0.25 0.5 1 1.5 2 9 Corduroy Tank 1 1 14 13 7 2 15 5 0 4 Miles 5 Doagie Spr. 5 16 9 Beechnut Tank 4 0 17 6 13 18 n 8 14 yo 1 15 an Q C Deadman Tank 16 D Coordinate System: NAD 1983 UTM Zone 12NTransverse Mercator 3 3 3 17 0 r C 2 Sawmill 1 0 Rock 7 18 a Alamosa 13 w 6 1 Spr. Core 14 Attention: Reilly 6 Dirt Tank 8 15 0 Peak 14 Dev. Tank 3 Clay 4 15 59 16 Gila National Forest uses the most current n 0 16 S o 17 13 Santana 8163 1 17 3 y Doubleheader #2 Tank 18 Fence Tank Cr. -

America's Wilderness Trail

Trail Protecti n The Pacific Crest Trail: America’s Wilderness Trail By Mike Dawson, PCTA Trail Operations Director To maintain and defend for the enjoyment of nature lovers the PACIFIC CREST TRAILWAY as a primitive wilderness pathway in an environment of solitude, free “from the sights and sounds of a mechanically disturbed Nature. – PCT System Conference mission, appearing in many publications and at the bottom of correspondence in the 1940s Many of us make the mistake of believing that the notion of set- The concepts of preserving wilderness” and building long-distance ting aside land in its natural condition with minimal influence trails were linked from those earliest days and were seen by leaders by man’s hand or of creating long-distance trails in natural set- of the time as facets of the same grand scheme. It seems clear that Mtings began with the environmental movement of the 1960s and one of the entities developed in those days has always been the set into the national consciousness with the passage of the 1964 epitome of the connection between those movements – the Pacific Wilderness Act and the 1968 National Trails System Act. Crest National Scenic Trail. But the development of these preservation concepts predates In recent articles in the PCT Communicator, writers have talked these landmark congressional acts by 40 years. A group of revolu- about the current association between the PCT and wilderness in tionary thinkers planted the seeds of these big ideas in the 1920s, this, the 50th anniversary of the Wilderness Act. Few are aware 1930s and 1940s. -

A WILDERNESS-FOREVER FUTURE a Short History of the National Wilderness Preservation System

A WILDERNESS-FOREVER FUTURE A Short History of the National Wilderness Preservation System A PEW WILDERNESS CENTER RESEARCH REPORT A WILDERNESS-FOREVER FUTURE A Short History of the National Wilderness Preservation System DOUGLAS W. SCOTT Here is an American wilderness vision: the vision of “a wilderness- forever future.” This is not my phrase, it is Howard Zahniser’s. And it is not my vision, but the one that I inherited, and that you, too, have inherited, from the wilderness leaders who went before. A Wilderness-Forever Future. Think about that. It is It is a hazard in a movement such as ours that the core idea bound up in the Wilderness Act, which newer recruits, as we all once were, may know too holds out the promise of “an enduring resource of little about the wilderness work of earlier generations. wilderness.” It is the idea of saving wilderness forever Knowing something of the history of wilderness —in perpetuity. preservation—nationally and in your own state— is important for effective wilderness advocacy. In Perpetuity. Think of the boldness of that ambition! As Zahniser said: “The wilderness that has come to us The history of our wilderness movement and the char- from the eternity of the past we have the boldness to acter and methods of those who pioneered the work project into the eternity of the future.”1 we continue today offer powerful practical lessons. The ideas earlier leaders nurtured and the practical tools Today this goal may seem obvious and worthy, but and skills they developed are what have brought our the goal of preserving American wilderness in per- movement to its present state of achievement. -

Guide to the Microfilm Edition of the Papers of Ernest Oberholtzer

GUIDE TO THE MICROFILM EDITION of the PAPERS OF ERNEST OBERHOLTZER Gregory Kinney _~ Minnesota Historical Society '!&1l1 Division of Library and Archives 1989 Copyright © by Minnesota Historical Society The Oberholtzer Papers were microfilmed and this guide printed with funds provided by grants from the Ernest C. Oberholtzer Foundation and the Quetico-Superior Foundation. -.-- -- - --- ~?' ~:':'-;::::~. Ernest Oberholtzer in his Mallard Island house on Rainy Lake in the late 1930s. Photo by Virginia Roberts French. Courtesy Minnesota Historical Society. Map of Arrowhead Region L.a"(.e~se\"C ~ I o A' .---.....; ., ; , \~ -'\ ~ • ~ fI"" i Whitefish---- Lake Fowl Lake ~/ ~ '""'-- F . O)"~"~'t\ ~~ , .tV "" , I -r-- ~Rlucr~ v'" '" Reprinted from Saving Quetico-Superior: A Land Set Apart, by R. Newell Searle, copyright@ 1977 by the Minnesota Historical Society, Used with permission. TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE .•• INTRODUCTION. 1 BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH 2 ARRANGEMENT NOTE 5 SERIES DESCRIPTIONS: Biographical Information 8 Personal Correspondence and Related Papers 9 Short Stories, Essays, and Other Writings 14 Miscellaneous Notes. • • 19 Journals and Notebooks • 20 Flood Damage Lawsuit Files 34 Quetico-Superior Papers • 35 Wilderness Society Papers • 39 Andrews Family Papers •• 40 Personal and Family Memorabilia and Other Miscellany 43 ROLL CONTENTS LIST • 44 RELATED COLLECTIONS 48 PREFACE This micl'ofilm edition represents the culmination of twenty-five years of efforts to preserve the personal papers of Ernest Carl Oberholtzer, The acquisition, processing, conservation, and microfilming of the papers has been made possible through the dedicated work and generous support of the Ernest C, Oberholtzer Foundation and the members of its board. Additional grant support was received from the Quetico-Superior Foundation. -

Consensus Comments on the San Gabriel National Monument Plan and Draft Environmental Analysis (October 31, 2016)

SAN GABRIEL MOUNTAINS COMMUNITY COLLABORATIVE Comments to the Angeles National Forest Contents San Gabriel Mountains Community Collaborative Unified Comments (August 11, 2015) .................................................................................... 2 San Gabriel Mountains Community Collaborative Consensus Comments on the San Gabriel National Monument Plan and Draft Environmental Analysis (October 31, 2016) .................................................................. 11 Press Release on Consensus Comments (November 2, 2016)............... 60 San Gabriel Mountains Community Collaborative Unified Comments August 11, 2015 Angeles National Forest ATTN: Justin Seastrand 701 North Santa Anita Avenue Arcadia, CA 91006 Dear Mr. Seastrand, The San Gabriel Mountains Community Collaborative (SGMCC) is pleased to provide to the U.S. Forest Service (USFS) our joint comments regarding the San Gabriel Mountains National Monument (Monument) “Need to Change” Analysis. The SGMCC consists of approximately 45 members representing a full range of interests (academic, business, civil rights, community, conservancies, cultural, environmental, environmental justice, ethnic diversity, education, youth, state and local government, Native American, public safety, recreation, special use permit holders, land lease holders, transportation, utilities, and water rights holders) associated with the Monument. The mission of the SGMCC is to: “Represent the general public by integrating diverse perspectives to identify, analyze, prioritize and advocate -

Data Set Listing (May 1997)

USDA Forest Service Air Resource Monitoring System Existing Data Set Listing (May 1997) Air Resource Monitoring System (ARMS) Data Set Listing May 1997 Contact Steve Boutcher USDA Forest Service National Air Program Information Manager Portland, OR (503) 808-2960 2 Table of Contents INTRODUCTION ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 9 DATA SET DESCRIPTIONS -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------10 National & Multi-Regional Data Sets EPA’S EASTERN LAKES SURVEY ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------11 EPA’S NATIONAL STREAM SURVEY ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------12 EPA WESTERN LAKES SURVEY------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------13 FOREST HEALTH MONITORING (FHM) LICHEN MONITORING-------------------------------------------------14 FOREST HEALTH MONITORING (FHM) OZONE BIOINDICATOR PLANTS ----------------------------------15 IMPROVE AEROSOL MONITORING--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------16 IMPROVE NEPHELOMETER ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------17 IMPROVE TRANSMISSOMETER ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------18 NATIONAL ATMOSPHERIC DEPOSITION PROGRAM/ NATIONAL TRENDS NETWORK----------------19 NATIONAL -

Table 7 - National Wilderness Areas by State

Table 7 - National Wilderness Areas by State * Unit is in two or more States ** Acres estimated pending final boundary determination + Special Area that is part of a proclaimed National Forest State National Wilderness Area NFS Other Total Unit Name Acreage Acreage Acreage Alabama Cheaha Wilderness Talladega National Forest 7,400 0 7,400 Dugger Mountain Wilderness** Talladega National Forest 9,048 0 9,048 Sipsey Wilderness William B. Bankhead National Forest 25,770 83 25,853 Alabama Totals 42,218 83 42,301 Alaska Chuck River Wilderness 74,876 520 75,396 Coronation Island Wilderness Tongass National Forest 19,118 0 19,118 Endicott River Wilderness Tongass National Forest 98,396 0 98,396 Karta River Wilderness Tongass National Forest 39,917 7 39,924 Kootznoowoo Wilderness Tongass National Forest 979,079 21,741 1,000,820 FS-administered, outside NFS bdy 0 654 654 Kuiu Wilderness Tongass National Forest 60,183 15 60,198 Maurille Islands Wilderness Tongass National Forest 4,814 0 4,814 Misty Fiords National Monument Wilderness Tongass National Forest 2,144,010 235 2,144,245 FS-administered, outside NFS bdy 0 15 15 Petersburg Creek-Duncan Salt Chuck Wilderness Tongass National Forest 46,758 0 46,758 Pleasant/Lemusurier/Inian Islands Wilderness Tongass National Forest 23,083 41 23,124 FS-administered, outside NFS bdy 0 15 15 Russell Fjord Wilderness Tongass National Forest 348,626 63 348,689 South Baranof Wilderness Tongass National Forest 315,833 0 315,833 South Etolin Wilderness Tongass National Forest 82,593 834 83,427 Refresh Date: 10/14/2017 -

Fiscal Impact Reports (Firs) Are Prepared by the Legislative Finance Committee (LFC) for Standing Finance Committees of the NM Legislature

Fiscal impact reports (FIRs) are prepared by the Legislative Finance Committee (LFC) for standing finance committees of the NM Legislature. The LFC does not assume responsibility for the accuracy of these reports if they are used for other purposes. Current FIRs (in HTML & Adobe PDF formats) are available on the NM Legislative Website (www.nmlegis.gov). Adobe PDF versions include all attachments, whereas HTML versions may not. Previously issued FIRs and attachments may be obtained from the LFC in Suite 101 of the State Capitol Building North. F I S C A L I M P A C T R E P O R T ORIGINAL DATE 02/07/13 SPONSOR Herrell/Martinez LAST UPDATED 02/18/13 HB 292 SHORT TITLE Transfer of Public Land Act SB ANALYST Weber REVENUE (dollars in thousands) Recurring Estimated Revenue Fund or Affected FY13 FY14 FY15 Nonrecurring (See Narrative) There (See Narrative) There may be additional may be additional Recurring General Fund revenue in future years. revenue in future years. (Parenthesis ( ) Indicate Revenue Decrease ESTIMATED ADDITIONAL OPERATING BUDGET IMPACT (dollars in thousands) 3 Year Recurring or Fund FY13 FY14 FY15 Total Cost Nonrecurring Affected General Total $100.0 $100.0 $200.0 Recurring Fund (Parenthesis ( ) Indicate Expenditure Decreases) Duplicate to SB 404 SOURCES OF INFORMATION LFC Files Responses Received From Administrative Office of the Courts (AOC) General Services Department (GSD) Economic Development Department (EDD) Department of Cultural Affairs (DCA) Energy, Minerals and Natural Resources Department (EMNRD) State Land Office (SLO) Department of Transportation (DOT) Department of Finance and Administration (DFA) House Bill 292 – Page 2 SUMMARY Synopsis of Bill House Bill 292 (HB 292) is the Transfer of Public Lands Act. -

A Path Through the Wilderness: the Story of Forest Road

A Path Through the Wilderness: The Story of Forest Road 150 Gila National Forest Erin Knolles Assistant Forest Archeologist March 2016 1 National Forest System Road 150 [commonly referred to as Forest Road (FR) 150], begins within the confines of the Gila National Forest and stretches north about 55 miles from NM 35 near Mimbres past Beaverhead Work Center to NM 163 north of the Gila National Forest boundary. FR 150 is the main road accessing this area of the Gila National Forest. Its location between two Wilderness Areas, Aldo Leopold and the Gila, makes it an important corridor for public access, as well as, administrative access for the Gila National Forest. Forest Road 150: The Name and a Brief History FR150 has been known by several names. The road was first called the North Star Road by the residents of Grant County and the U.S. Military when it was constructed in the 1870s.1 Today, the route is still called the North Star Road and used interchangeably with FR 150. Through most of the 20th century, FR 150 was under New Mexico state jurisdiction and named New Mexico (NM) 61.2 Of interest is that topographical maps dating to at least 1980, list the road as both NM 61 and FR 150.3 This is interesting because, today, it is common practice not to give roads Forest Service names unless they are under the jurisdiction of the Forest Service. In addition, the 1974 Gila National Forest Map refers to the route as FR 150.4 There is still some question when the North Star Road and NM 61 became known as FR 150. -

Highways in Harmony Grant Siijui: Y Muiiniiiinz I Jaiiau&L Fart

The Asheville, North Carolina Chamber of Commerce NATIONAL PARK SERVICE AS In an effort to appease both wilderness advocates and DESIGN AND CONSTRUCTION OF promoted construction of a "Skyway" along the crest of road proponents, GRSM Superintendent George Fry Highways in Harmony the Smokies in 1932. The proposed road would run along MEDIATOR proposed six smaller wilderness areas rather than the two GREAT SMOKY MOUNTAINS Q 1 US 5 Si^tS § < -s sit J the ridge of the mountains much like Shenandoah's The debate between road proponents and wilderness larger ones promoted by the Smoky Mountains Hiking ROADS & BRIDGES Skyline Drive. In July of that year GRSM officials advocates continued to influence road building in GRSM Club. Most importantly, Fry situated these six tracts so as Thousand of years of geological change and erosion have Grant Siijui: y announced that the Park would go ahead with this project, during the post World War II era. This is most evident in to leave a swath of undesignated land running up and over shaped the Great Smoky Mountains, which are and in November and December the Bureau of Public the controversy over the proposed Northshore Road that the crest of the Smokies to allow construction of a 32-mile characterized by high mountain peaks, steep hillsides, Muiiniiiinz Roads inspected the proposed route. was to run along Fontana Lake from Bryson City to motor road connecting Townsend, Tennessee with Bryson deep river valleys, and fertile coves. This difficult terrain Fontana Dam. According to a 1943 agreement, the City, North Carolina. This "Transmountain Highway," and underlying bedrock presented numerous challenges i Jaiiau&l Fart In response to such actions, in 1934 a local lawyer named National Park Service agreed to construct a new road Fry believed, would not only relieve congestion along for the designer of the roads in Great Smoky Mountains Harvey Broome invited Marshall and McKaye to within park boundaries along the north shore of Fontana Newfound Gap Road but would also appeal to North North Carolina, Tennessee National Park. -

Jaguar Critical Habitat Comments in Response to 71 FR 50214-50242 (Aug

October 19, 2012 Submitted on-line via www.regulations.gov, Docket No. FWS-R2-ES-2012-0042. Re: Jaguar critical habitat comments in response to 71 FR 50214-50242 (Aug. 20, 2012). To Whom it May Concern, The Center for Biological Diversity supports the designation of the entirety of the areas that the Fish and Wildlife Service proposes as critical habitat. However, these areas are not sufficient to conserve the jaguar in the United States. Nor does the Service’s itemization of threats to critical habitat areas cover the array of actions that would in fact destroy or adversely modify them. As we explain in detail in the comments below and through evidence presented in our appended letter of 10/1/2012 on the Recovery Outline for the Jaguar, we request seven principal changes in the final critical habitat designation rule, as follows: 1. The following additional mountain ranges within the current boundary of the Northwestern Recovery Unit (as described in the April 2012 Recovery Outline for the Jaguar) should be designated as critical habitat: in Arizona, the Chiricahua, Dos Cabezas, Dragoon and Mule mountains, and in New Mexico the Animas and adjoining Pyramid mountains. 2. The following additional “sky island” mountain ranges outside of the current boundaries of the Northwestern Recovery Unit should be designated as critical habitat: In New Mexico, the Alama Hueco, Big Hatchet, Little Hatchet, Florida, West and East Potrillo, Cedar and Big Burro mountains; in Arizona, the Galiuro, Santa Teresa, Pinaleno, Whitlock, Santa Catalina and Rincon mountains. Straddling both states, the Peloncillo Mountains north of the current boundaries of the Northwestern Recovery Unit should also be designated 3.