A Path Through the Wilderness: the Story of Forest Road

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The AILING GILA WILDERNESS

The AILING GILA WILDERNESS A PICTORIAL REVIEW The AILING GILA WILDERNESS A PICTORIAL REVIEW ~ Gila Wilderness by RONALD J. WHITE Division Director M.S. Wildlife Science, B.S. Range Science Certified Wildlife Biologist Division of Agricultural Programs and Resources New Mexico Department of Agriculture December 1995 ACknoWledgments Many people who live in the vicinity of the Gila National Forest are concerned about the degraded condition of its resources. This document resulted from my discussions with some of them, and the conclusion that something must be started to address the complex situation. Appreciation is extended to the participants in this project, who chose to get involved, and whose assistance and knowledge contributed significantly to the project. Their knowledge ofthe country, keen observations, and perceptive interpretations of the situation are unsurpassed. As a bonus, they are a pleasure to be around. Kit Laney - President, Gila Permittee's Association, and lifetime area rancher, Diamond Bar Cattle Co. Matt Schneberger - Vice President, Gila Permittee's Association, and lifetime area rancher, Rafter Spear Ranch. Becky Campbell Snow and David Snow - Gila Hot Springs Ranch. Becky is a lifetime area guide and outfitter. The Snows provided the livestock and equipment for both trips to review and photograph the Glenn Allotment in the Gila Wilderness. Wray Schildknecht - ArrowSun Associates, B.S. Wildlife Science, Reserve, NM. D. A. "Doc" and Ida Campbell, Gila Hot Springs Ranch, provided the precipitation data. They have served as volunteer weather reporters for the National Weather Service Forecast Office since 1957, and they are longtime area ranchers, guides, and outfitters. Their gracious hospitality at headquarters was appreciated by everyone. -

Wilderness Visitors and Recreation Impacts: Baseline Data Available for Twentieth Century Conditions

United States Department of Agriculture Wilderness Visitors and Forest Service Recreation Impacts: Baseline Rocky Mountain Research Station Data Available for Twentieth General Technical Report RMRS-GTR-117 Century Conditions September 2003 David N. Cole Vita Wright Abstract __________________________________________ Cole, David N.; Wright, Vita. 2003. Wilderness visitors and recreation impacts: baseline data available for twentieth century conditions. Gen. Tech. Rep. RMRS-GTR-117. Ogden, UT: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. 52 p. This report provides an assessment and compilation of recreation-related monitoring data sources across the National Wilderness Preservation System (NWPS). Telephone interviews with managers of all units of the NWPS and a literature search were conducted to locate studies that provide campsite impact data, trail impact data, and information about visitor characteristics. Of the 628 wildernesses that comprised the NWPS in January 2000, 51 percent had baseline campsite data, 9 percent had trail condition data and 24 percent had data on visitor characteristics. Wildernesses managed by the Forest Service and National Park Service were much more likely to have data than wildernesses managed by the Bureau of Land Management and Fish and Wildlife Service. Both unpublished data collected by the management agencies and data published in reports are included. Extensive appendices provide detailed information about available data for every study that we located. These have been organized by wilderness so that it is easy to locate all the information available for each wilderness in the NWPS. Keywords: campsite condition, monitoring, National Wilderness Preservation System, trail condition, visitor characteristics The Authors _______________________________________ David N. -

Gila National Forest Fact Sheet

CENTER FOR BIOLOGICAL DIVERSITY Because life is good. GILA NATIONAL FOREST The Gila National Forest occupies 3.3 million acres in southwestern New Mexico and is home to the Mexican spotted owl, Mexican gray wolf, Gila chub, southwestern willow flycatcher, loach minnow, and spikedace. The forest also encompasses the San Francisco, Gila, and Mimbres Rivers, and the scenic Burros Mountains. In the 1920s, conservation pioneer Aldo Leopold persuaded the Forest Service to set aside more than half a million acres of the Gila River’s headwaters as wilderness. This wild land became the nation’s first designated wilderness Photo © Robin Silver — the Gila Wilderness Area — in 1924. The Gila National Forest is home to threatened Mexican spotted owls and many other imperiled species. n establishing the Gila Wilderness Area, the Gila The Gila National Forest’s plan by the numbers: National Forest set a precedent for protection Iof our public lands. Sadly, it appears that • 114,000: number of acres of land open to safeguarding the Gila for the enjoyment of future continued destruction; generations is no longer management’s top priority. • 4,764: number of miles of proposed motorized On September 11, 2009, the Gila National Forest roads and trails in the Gila National Forest, equal to released its travel-management plan, one of the worst the distance from Hawaii to the North Pole; plans developed for southwestern forests. Pressure • $7 million: road maintenance backlog accumulated from vocal off-road vehicle users has overwhelmed the by the Gila National Forest; Forest Service, which has lost sight of its duty to protect • less than 3 percent: proportion of forest visitors this land for future generations. -

Butch Cassidy Roamed Incognito in Southwest New Mexico

Nancy Coggeshall I For The New Mexican Hideout in the Gila Butch Cassidy roamed incognito in southwest New Mexico. Hideout in the Gila utch Cassidy’s presence in southwestern New Mexico is barely noted today. Notorious for his successful bank Butch Cassidy roamed and train robberies at the turn of the 20th century, incognito in southwest Cassidy was idealized and idolized as a “gentleman out- New Mexico wilderness Blaw” and leader of the Wild Bunch. He and various members of the • gang worked incognito at the WS Ranch — set between Arizona’s Blue Range and San Carlos Apache Reservation to the west and the Nancy Coggeshall rugged Mogollon Mountains to the east — from February 1899 For The New Mexican until May 1900. Descendants of pioneers and ranchers acquainted with Cassidy tell stories about the man their ancestors knew as “Jim Lowe.” Nancy Thomas grew up hearing from her grandfather Clarence Tipton and others that Cassidy was a “man of his word.” Tipton was the foreman at the WS immediately before Cassidy’s arrival. The ranch sits at the southern end of the Outlaw Trail, a string of accommodating ranches and Wild Bunch hideouts stretching from Montana and the Canadian border into Mexico. The country surrounding the WS Ranch is forbidding; volcanic terrain cleft with precipitously angled, crenelated canyon walls defies access. A “pretty hard layout,” local old-timer Robert Bell told Lou Blachly, whose collection of interviews with pioneers — conducted PROMIENT PLACES - between 1942 and 1953 — are housed at the University of New OUTLAW TRAIL Mexico. What better place to dodge the law? 1. -

LIGHTNING FIRES in SOUTHWESTERN FORESTS T

This file was created by scanning the printed publication. Errors identified by the software have been corrected; however, some errors may remain. LIGHTNING FIRES IN SOUTHWESTERN FORESTS t . I I LIGHT~ING FIRES IN SOUTHWESTERN FORESTS (l) by Jack S. Barrows Department of Forest and Wood Sciences College of Forestry and Natural Resources Colorado State University Fort Collins, CO 80523 (1) Research performed for Northern Forest Fire Laboratory, Intermountain Forest and Range Experiment Station under cooperative agreement 16-568 CA with Rocky Mountain For est and Range Experiment Station. Final Report May 1978 n LIB RARY COPY. ROCKY MT. FO i-< t:S'f :.. R.l.N~ EX?f.lt!M SN T ST.A.1101'1 . - ... Acknowledgementd r This research of lightning fires in Sop thwestern forests has been ? erformed with the assistan~e and cooperation of many individuals and agencies. The idea for the research was suggested by Dr. Donald M. Fuquay and Robert G. Baughman of the Northern Forest Fire Laboratory. The Fire Management Staff of U. S. Forest Service Region Three provided fire data, maps, rep~rts and briefings on fire p~enomena. Special thanks are expressed to James F. Mann for his continuing assistance in these a ctivities. Several members of national forest staffs assisted in correcting fire report errors. At CSU Joel Hart was the principal graduate 'research assistant in organizing the data, writing computer programs and handling the extensive computer operations. The initial checking of fire data tapes and com puter programming was performed by research technician Russell Lewis. Graduate Research Assistant Rick Yancik and Research Associate Lee Bal- ::. -

General Vertical Files Anderson Reading Room Center for Southwest Research Zimmerman Library

“A” – biographical Abiquiu, NM GUIDE TO THE GENERAL VERTICAL FILES ANDERSON READING ROOM CENTER FOR SOUTHWEST RESEARCH ZIMMERMAN LIBRARY (See UNM Archives Vertical Files http://rmoa.unm.edu/docviewer.php?docId=nmuunmverticalfiles.xml) FOLDER HEADINGS “A” – biographical Alpha folders contain clippings about various misc. individuals, artists, writers, etc, whose names begin with “A.” Alpha folders exist for most letters of the alphabet. Abbey, Edward – author Abeita, Jim – artist – Navajo Abell, Bertha M. – first Anglo born near Albuquerque Abeyta / Abeita – biographical information of people with this surname Abeyta, Tony – painter - Navajo Abiquiu, NM – General – Catholic – Christ in the Desert Monastery – Dam and Reservoir Abo Pass - history. See also Salinas National Monument Abousleman – biographical information of people with this surname Afghanistan War – NM – See also Iraq War Abousleman – biographical information of people with this surname Abrams, Jonathan – art collector Abreu, Margaret Silva – author: Hispanic, folklore, foods Abruzzo, Ben – balloonist. See also Ballooning, Albuquerque Balloon Fiesta Acequias – ditches (canoas, ground wáter, surface wáter, puming, water rights (See also Land Grants; Rio Grande Valley; Water; and Santa Fe - Acequia Madre) Acequias – Albuquerque, map 2005-2006 – ditch system in city Acequias – Colorado (San Luis) Ackerman, Mae N. – Masonic leader Acoma Pueblo - Sky City. See also Indian gaming. See also Pueblos – General; and Onate, Juan de Acuff, Mark – newspaper editor – NM Independent and -

Trails in the Aldo Leopold Wilderness Area Recently Maintained & Cleared

l y R. 13 W. R. 12 W. R. 11 W. r l R. 10 W. t R. 9 W. R. 8 W. i r e t e 108°0'W m 107°45'W a v w o W a P S S le 11 Sawmill t Boundary Tank F t 6 40 10 i 1 6 Peak L 5 6 7M 10 11 9 1:63,360 0 0 8 9 12 8 8350 anyon Houghton Spring 4 7 40 7 5 7 T e C 1 in = 1 miles 11 12 4 71 7 7 0 Klin e C 10 0 C H 6 0 7 in Water anyon 8 9 6 a 4 0 Ranch P 4065A 7 Do 6 n 4 073Q (printed on 36" x 42" portrait layout) Houghton ag Z y 4 Well 12 Corduroy Corral y Doagy o 66 11 n 5 aska 10 Spr. Spr. Tank K Al 0 0.25 0.5 1 1.5 2 9 Corduroy Tank 1 1 14 13 7 2 15 5 0 4 Miles 5 Doagie Spr. 5 16 9 Beechnut Tank 4 0 17 6 13 18 n 8 14 yo 1 15 an Q C Deadman Tank 16 D Coordinate System: NAD 1983 UTM Zone 12NTransverse Mercator 3 3 3 17 0 r C 2 Sawmill 1 0 Rock 7 18 a Alamosa 13 w 6 1 Spr. Core 14 Attention: Reilly 6 Dirt Tank 8 15 0 Peak 14 Dev. Tank 3 Clay 4 15 59 16 Gila National Forest uses the most current n 0 16 S o 17 13 Santana 8163 1 17 3 y Doubleheader #2 Tank 18 Fence Tank Cr. -

Gila Cliff Dwellings National Monument Foundation Document

NATIONAL PARK SERVICE • U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Foundation Document Overview Gila Cliff Dwellings National Monument New Mexico Contact Information For more information about the Gila Cliff Dwellings National Monument Foundation Document, contact: [email protected] or (575) 536-9461 or write to: Superintendent, Gila Cliff Dwellings National Monument, HC 68 Box 100, Silver City, NM 88061 Purpose Significance Significance statements express why Gila Cliff Dwellings National Monument resources and values are important enough to merit national park unit designation. Statements of significance describe why an area is important within a global, national, regional, and systemwide context. These statements are linked to the purpose of the park unit, and are supported by data, research, and consensus. Significance statements describe the distinctive nature of the park and inform management decisions, focusing efforts on preserving and protecting the most important resources and values of the park unit. As the only unit of the national park system dedicated to the Mogollon • Gila Cliff Dwellings National Monument protects the largest culture, the purpose of GILA CLIFF known Mogollon cliff dwellings site and interprets for the DWELLINGS NATIONAL MONUMENT is to public well-preserved structures built more than 700 years protect, preserve, and interpret the ago. Architectural features and associated artifacts are cliff dwellings and associated sites and exceptionally preserved within the natural caves of Cliff artifacts of that culture, set apart for Dweller Canyon. its educational and scientific interest • The TJ site of the monument includes one of the last and public enjoyment within a remote, unexcavated, large Mimbres Mogollon pueblo settlements pristine natural setting. -

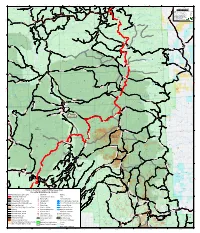

Trails in the Gila Wilderness Area Recently

R. 20 W. R. 19 W. R. 18 W. R. 17 W. R. 16 W. R. 15 W. R. 14 W. R. 13 W. R. 12 W. R. 11 W. 108°45'W 108°30'W 108°15'W 108°0'W E I D G Spring Upper R 10 C Negrito A R B Canyon 9 a n 5 Black 9J Long Cyn. Burnt 12 B Pine 4065A 7 8 Doagy n Barlow Tank 23 o T 4 l Houghton F y 4 1 e Pasture 0 a 1 n y 6 1:63,360 2 6 Reserve Ranger District RD anyo 12 o Steer 1 k Quaking Aspen Cr. 6 C 6 3 949 97 5 3 Corduroy Tank 4 Tank D n Gooseb Cabin Tank I 4 J c Tank 4 0 Doagy Spr. n ea a erry 1 11 99 5 dm a Tank 6 1 4 Arroyo Well 1 6 X an L 40 k 10 1 in = 1 miles C Tank 6 t 40 9 Houghton Corduroy Corral Spr. 5 s Barlow 6 Negrito R 8 (printed on 36" x 54" landscapeDoagie Spr. layout) 0 Dead Man Spr. o S 0 M 7 S 4 L a C U a 12 Water Well Beechnut Tank Basin Hogan Spr. va a Mountain 12 1 10 11 406 Bill Lewis S Deadman 6 Barlow ep g n 11 6 South n 9 Z De e n B 10 0 7 8 n Pine 4 C anyo y 9 r 12 0 0.25 0.5 1 1.5 2 Tank anyo Cabin 9 o 9 Tank 8 8583 4 B 11 g Bonus Basin C 1 n 12 7 Fork Spr. -

Lincoln National Forest

Chapter 1: Introduction In Ecological and Biological Diversity of National Forests in Region 3 Bruce Vander Lee, Ruth Smith, and Joanna Bate The Nature Conservancy EXECUTIVE SUMMARY We summarized existing regional-scale biological and ecological assessment information from Arizona and New Mexico for use in the development of Forest Plans for the eleven National Forests in USDA Forest Service Region 3 (Region 3). Under the current Planning Rule, Forest Plans are to be strategic documents focusing on ecological, economic, and social sustainability. In addition, Region 3 has identified restoration of the functionality of fire-adapted systems as a central priority to address forest health issues. Assessments were selected for inclusion in this report based on (1) relevance to Forest Planning needs with emphasis on the need to address ecosystem diversity and ecological sustainability, (2) suitability to address restoration of Region 3’s major vegetation systems, and (3) suitability to address ecological conditions at regional scales. We identified five assessments that addressed the distribution and current condition of ecological and biological diversity within Region 3. We summarized each of these assessments to highlight important ecological resources that exist on National Forests in Arizona and New Mexico: • Extent and distribution of potential natural vegetation types in Arizona and New Mexico • Distribution and condition of low-elevation grasslands in Arizona • Distribution of stream reaches with native fish occurrences in Arizona • Species richness and conservation status attributes for all species on National Forests in Arizona and New Mexico • Identification of priority areas for biodiversity conservation from Ecoregional Assessments from Arizona and New Mexico Analyses of available assessments were completed across all management jurisdictions for Arizona and New Mexico, providing a regional context to illustrate the biological and ecological importance of National Forests in Region 3. -

Journal of Wilderness

INTERNATIONAL Journal of Wilderness DECEMBER 2005 VOLUME 11, NUMBER 3 FEATURES SCIENCE AND RESEARCH 3 Is Eastern Wilderness ”Real”? PERSPECTIVES FROM THE ALDO LEOPOLD WILDERNESS RESEARCH INSTITUTE BY REBECCA ORESKES 30 Social and Institutional Influences on SOUL OF THE WILDERNESS Wilderness Fire Stewardship 4 Florida Wilderness BY KATIE KNOTEK Working with Traditional Tools after a Hurricane BY SUSAN JENKINS 31 Wilderness In Whose Backyard? BY GARY T. GREEN, MICHAEL A. TARRANT, UTTIYO STEWARDSHIP RAYCHAUDHURI, and YANGJIAN ZHANG 7 A Truly National Wilderness Preservation System BY DOUGLAS W. SCOTT EDUCATION AND COMMUNICATION 39 Changes in the Aftermath of Natural Disasters 13 Keeping the Wild in Wilderness When Is Too Much Change Unacceptable to Visitors? Minimizing Nonconforming Uses in the National Wilderness Preservation System BY JOSEPH FLOOD and CRAIG COLISTRA BY GEORGE NICKAS and KEVIN PROESCHOLDT 19 Developing Wilderness Indicators on the INTERNATIONAL PERSPECTIVES White Mountain National Forest 42 Wilderness Conservation in a Biodiversity Hotspot BY DAVE NEELY BY RUSSELL A. MITTERMEIER, FRANK HAWKINS, SERGE RAJAOBELINA, and OLIVIER LANGRAND 22 Understanding the Cultural, Existence, and Bequest Values of Wilderness BY RUDY M. SCHUSTER, H. KEN CORDELL, and WILDERNESS DIGEST BRAD PHILLIPS 46 Announcements and Wilderness Calendar 26 8th World Wilderness Congress Generates Book Review Conservation Results 48 How Should America’s Wilderness Be Managed? BY VANCE G. MARTIN edited by Stuart A. Kallen REVIEWED BY JOHN SHULTIS FRONT COVER The magnificent El Carmen escaprment, one of the the “sky islands” of Coahuilo, Mexico. Photo by Patricio Robles Gil/Sierra Madre. INSET Ancient grain grinding site, Maderas del Carmen, Coahuilo, Mexico. Photo by Vance G. -

State No. Description Size in Cm Date Location

Maps State No. Description Size in cm Date Location National Forests in Alabama. Washington: ALABAMA AL-1 49x28 1989 Map Case US Dept. of Agriculture, Forest Service. Bankhead National Forest (Bankhead and Alabama AL-2 66x59 1981 Map Case Blackwater Districts). Washington: US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service. Side A : Coronado National Forest (Nogales A: 67x72 ARIZONA AZ-1 1984 Map Case Ranger District). Washington: US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service. B: 67x63 Side B : Coronado National Forest (Sierra Vista Ranger District). Side A : Coconino National Forest (North A:69x88 Arizona AZ-2 1976 Map Case Half). Washington: US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service. B:69x92 Side B : Coconino National Forest (South Half). Side A : Coronado National Forest (Sierra A:67x72 Arizona AZ-3 1976 Map Case Vista Ranger District. Washington: US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service. B:67x72 Side B : Coronado National Forest (Nogales Ranger District). Prescott National Forest. Washington: US Arizona AZ-4 28x28 1992 Map Case Department of Agriculture, Forest Service. Kaibab National Forest (North Unit). Arizona AZ-5 68x97 1967 Map Case Washington: US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service. Prescott National Forest- Granite Mountain Arizona AZ-6 67x48.5 1993 Map Case Wilderness. Washington: US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service. Side A : Prescott National Forest (East Half). A:111x75 Arizona AZ-7 1993 Map Case Washington: US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service. B:111x75 Side B : Prescott National Forest (West Half). Arizona AZ-8 Superstition Wilderness: Tonto National 55.5x78.5 1994 Map Case Forest. Washington: US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service. Arizona AZ-9 Kaibab National Forest, Gila and Salt River 80x96 1994 Map Case Meridian.