Preliminary Draft Land Management Plan for the Gila National Forest Catron, Grant, Hidalgo, and Sierra Counties, New Mexico

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wilderness Visitors and Recreation Impacts: Baseline Data Available for Twentieth Century Conditions

United States Department of Agriculture Wilderness Visitors and Forest Service Recreation Impacts: Baseline Rocky Mountain Research Station Data Available for Twentieth General Technical Report RMRS-GTR-117 Century Conditions September 2003 David N. Cole Vita Wright Abstract __________________________________________ Cole, David N.; Wright, Vita. 2003. Wilderness visitors and recreation impacts: baseline data available for twentieth century conditions. Gen. Tech. Rep. RMRS-GTR-117. Ogden, UT: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. 52 p. This report provides an assessment and compilation of recreation-related monitoring data sources across the National Wilderness Preservation System (NWPS). Telephone interviews with managers of all units of the NWPS and a literature search were conducted to locate studies that provide campsite impact data, trail impact data, and information about visitor characteristics. Of the 628 wildernesses that comprised the NWPS in January 2000, 51 percent had baseline campsite data, 9 percent had trail condition data and 24 percent had data on visitor characteristics. Wildernesses managed by the Forest Service and National Park Service were much more likely to have data than wildernesses managed by the Bureau of Land Management and Fish and Wildlife Service. Both unpublished data collected by the management agencies and data published in reports are included. Extensive appendices provide detailed information about available data for every study that we located. These have been organized by wilderness so that it is easy to locate all the information available for each wilderness in the NWPS. Keywords: campsite condition, monitoring, National Wilderness Preservation System, trail condition, visitor characteristics The Authors _______________________________________ David N. -

Gila National Forest Fact Sheet

CENTER FOR BIOLOGICAL DIVERSITY Because life is good. GILA NATIONAL FOREST The Gila National Forest occupies 3.3 million acres in southwestern New Mexico and is home to the Mexican spotted owl, Mexican gray wolf, Gila chub, southwestern willow flycatcher, loach minnow, and spikedace. The forest also encompasses the San Francisco, Gila, and Mimbres Rivers, and the scenic Burros Mountains. In the 1920s, conservation pioneer Aldo Leopold persuaded the Forest Service to set aside more than half a million acres of the Gila River’s headwaters as wilderness. This wild land became the nation’s first designated wilderness Photo © Robin Silver — the Gila Wilderness Area — in 1924. The Gila National Forest is home to threatened Mexican spotted owls and many other imperiled species. n establishing the Gila Wilderness Area, the Gila The Gila National Forest’s plan by the numbers: National Forest set a precedent for protection Iof our public lands. Sadly, it appears that • 114,000: number of acres of land open to safeguarding the Gila for the enjoyment of future continued destruction; generations is no longer management’s top priority. • 4,764: number of miles of proposed motorized On September 11, 2009, the Gila National Forest roads and trails in the Gila National Forest, equal to released its travel-management plan, one of the worst the distance from Hawaii to the North Pole; plans developed for southwestern forests. Pressure • $7 million: road maintenance backlog accumulated from vocal off-road vehicle users has overwhelmed the by the Gila National Forest; Forest Service, which has lost sight of its duty to protect • less than 3 percent: proportion of forest visitors this land for future generations. -

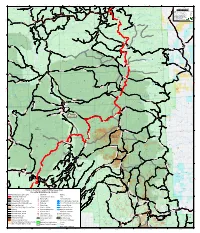

Nm Report 4-2-13.Indd

New Mexico TIM PALMER Rio Chama. Cover: Rio Grande. Letter from the President ivers are the great treasury of noted scientists and other experts reviewed the survey design, and biological diversity in the western state-specifi c experts reviewed the results for each state. RUnited States. As evidence mounts The result is a state-by-state list of more than 250 of the West’s that climate is changing even faster than we outstanding streams, some protected, some still vulnerable. The feared, it becomes essential that we create Great Rivers of the West is a new type of inventory to serve the sanctuaries on our best, most natural rivers modern needs of river conservation—a list that Western Rivers that will harbor viable populations of at-risk Conservancy can use to strategically inform its work. species—not only charismatic species like salmon, but a broad range of aquatic and This is one of 11 state chapters in the report. Also available are a terrestrial species. summary of the entire report, as well as the full report text. That is what we do at Western Rivers Conservancy. We buy land With the right tools in hand, Western Rivers Conservancy is to create sanctuaries along the most outstanding rivers in the West seizing once-in-a-lifetime opportunities to acquire and protect – places where fi sh, wildlife and people can fl ourish. precious streamside lands on some of America’s fi nest rivers. With a talented team in place, combining more than 150 years This is a time when investment in conservation can yield huge of land acquisition experience and offi ces in Oregon, Colorado, dividends for the future. -

LIGHTNING FIRES in SOUTHWESTERN FORESTS T

This file was created by scanning the printed publication. Errors identified by the software have been corrected; however, some errors may remain. LIGHTNING FIRES IN SOUTHWESTERN FORESTS t . I I LIGHT~ING FIRES IN SOUTHWESTERN FORESTS (l) by Jack S. Barrows Department of Forest and Wood Sciences College of Forestry and Natural Resources Colorado State University Fort Collins, CO 80523 (1) Research performed for Northern Forest Fire Laboratory, Intermountain Forest and Range Experiment Station under cooperative agreement 16-568 CA with Rocky Mountain For est and Range Experiment Station. Final Report May 1978 n LIB RARY COPY. ROCKY MT. FO i-< t:S'f :.. R.l.N~ EX?f.lt!M SN T ST.A.1101'1 . - ... Acknowledgementd r This research of lightning fires in Sop thwestern forests has been ? erformed with the assistan~e and cooperation of many individuals and agencies. The idea for the research was suggested by Dr. Donald M. Fuquay and Robert G. Baughman of the Northern Forest Fire Laboratory. The Fire Management Staff of U. S. Forest Service Region Three provided fire data, maps, rep~rts and briefings on fire p~enomena. Special thanks are expressed to James F. Mann for his continuing assistance in these a ctivities. Several members of national forest staffs assisted in correcting fire report errors. At CSU Joel Hart was the principal graduate 'research assistant in organizing the data, writing computer programs and handling the extensive computer operations. The initial checking of fire data tapes and com puter programming was performed by research technician Russell Lewis. Graduate Research Assistant Rick Yancik and Research Associate Lee Bal- ::. -

Trails in the Aldo Leopold Wilderness Area Recently Maintained & Cleared

l y R. 13 W. R. 12 W. R. 11 W. r l R. 10 W. t R. 9 W. R. 8 W. i r e t e 108°0'W m 107°45'W a v w o W a P S S le 11 Sawmill t Boundary Tank F t 6 40 10 i 1 6 Peak L 5 6 7M 10 11 9 1:63,360 0 0 8 9 12 8 8350 anyon Houghton Spring 4 7 40 7 5 7 T e C 1 in = 1 miles 11 12 4 71 7 7 0 Klin e C 10 0 C H 6 0 7 in Water anyon 8 9 6 a 4 0 Ranch P 4065A 7 Do 6 n 4 073Q (printed on 36" x 42" portrait layout) Houghton ag Z y 4 Well 12 Corduroy Corral y Doagy o 66 11 n 5 aska 10 Spr. Spr. Tank K Al 0 0.25 0.5 1 1.5 2 9 Corduroy Tank 1 1 14 13 7 2 15 5 0 4 Miles 5 Doagie Spr. 5 16 9 Beechnut Tank 4 0 17 6 13 18 n 8 14 yo 1 15 an Q C Deadman Tank 16 D Coordinate System: NAD 1983 UTM Zone 12NTransverse Mercator 3 3 3 17 0 r C 2 Sawmill 1 0 Rock 7 18 a Alamosa 13 w 6 1 Spr. Core 14 Attention: Reilly 6 Dirt Tank 8 15 0 Peak 14 Dev. Tank 3 Clay 4 15 59 16 Gila National Forest uses the most current n 0 16 S o 17 13 Santana 8163 1 17 3 y Doubleheader #2 Tank 18 Fence Tank Cr. -

Lincoln National Forest

Chapter 1: Introduction In Ecological and Biological Diversity of National Forests in Region 3 Bruce Vander Lee, Ruth Smith, and Joanna Bate The Nature Conservancy EXECUTIVE SUMMARY We summarized existing regional-scale biological and ecological assessment information from Arizona and New Mexico for use in the development of Forest Plans for the eleven National Forests in USDA Forest Service Region 3 (Region 3). Under the current Planning Rule, Forest Plans are to be strategic documents focusing on ecological, economic, and social sustainability. In addition, Region 3 has identified restoration of the functionality of fire-adapted systems as a central priority to address forest health issues. Assessments were selected for inclusion in this report based on (1) relevance to Forest Planning needs with emphasis on the need to address ecosystem diversity and ecological sustainability, (2) suitability to address restoration of Region 3’s major vegetation systems, and (3) suitability to address ecological conditions at regional scales. We identified five assessments that addressed the distribution and current condition of ecological and biological diversity within Region 3. We summarized each of these assessments to highlight important ecological resources that exist on National Forests in Arizona and New Mexico: • Extent and distribution of potential natural vegetation types in Arizona and New Mexico • Distribution and condition of low-elevation grasslands in Arizona • Distribution of stream reaches with native fish occurrences in Arizona • Species richness and conservation status attributes for all species on National Forests in Arizona and New Mexico • Identification of priority areas for biodiversity conservation from Ecoregional Assessments from Arizona and New Mexico Analyses of available assessments were completed across all management jurisdictions for Arizona and New Mexico, providing a regional context to illustrate the biological and ecological importance of National Forests in Region 3. -

Southwest NM Publication List

Southwest New Mexico Publication Inventory Draft Source of Document/Search Purchase Topic Category Keywords County Title Author Date Publication/Journal/Publisher Type of Document Method Price Geology 1 Geology geology, seismic Southwestern NM Six regionally extensive upper-crustal Ackermann, H.D., L.W. 1994 U.S. Geological Survey, Open-File Report 94- Electronic file USGS publication search refraction profiles, seismic refraction profiles in Southwest New Pankratz, D.P. Klein 695 (DJVU) http://pubs.er.usgs.gov/usgspubs/ southwestern New Mexico ofr/ofr94695 Mexico, 2 Geology Geology, Southwestern NM Magmatism and metamorphism at 1.46 Ga in Amato, J.M., A.O. 2008 In New Mexico Geological Society Fall Field Paper in Book http://nmgs.nmt.edu/publications/g $45.00 magmatism, the Burro Mountains, southwestern New Boullion, and A.E. Conference Guidebook - 59, Geology of the Gila uidebooks/59/ metamorphism, Mexico Sanders Wilderness-Silver City area, 107-116. Burro Mountains, southwestern New Mexico 3 Geology Geology, mineral Catron County Geology and mineral resources of York Anderson, O.J. 1986 New Mexico Bureau of Mines and Mineral Electronic file (PDF) NMBGMR search $10.00 for resources, York Ranch SE quadrangle, Cibola and Catron Resources Open File Report 220A, 22 pages. <http://geoinfo.nmt.edu/publicatio CD Ranch, Fence Counties, New Mexico ns/openfile/details.cfml?Volume=2 Lake, Catron, 20A> Cibola 4 Geology Geology, Zuni Salt Catron County Geology of the Zuni Salt Lake 7 1/2 Minute Anderson, O.J. 1994 New Mexico Bureau of Mines and -

Journal of Wilderness

INTERNATIONAL Journal of Wilderness DECEMBER 2005 VOLUME 11, NUMBER 3 FEATURES SCIENCE AND RESEARCH 3 Is Eastern Wilderness ”Real”? PERSPECTIVES FROM THE ALDO LEOPOLD WILDERNESS RESEARCH INSTITUTE BY REBECCA ORESKES 30 Social and Institutional Influences on SOUL OF THE WILDERNESS Wilderness Fire Stewardship 4 Florida Wilderness BY KATIE KNOTEK Working with Traditional Tools after a Hurricane BY SUSAN JENKINS 31 Wilderness In Whose Backyard? BY GARY T. GREEN, MICHAEL A. TARRANT, UTTIYO STEWARDSHIP RAYCHAUDHURI, and YANGJIAN ZHANG 7 A Truly National Wilderness Preservation System BY DOUGLAS W. SCOTT EDUCATION AND COMMUNICATION 39 Changes in the Aftermath of Natural Disasters 13 Keeping the Wild in Wilderness When Is Too Much Change Unacceptable to Visitors? Minimizing Nonconforming Uses in the National Wilderness Preservation System BY JOSEPH FLOOD and CRAIG COLISTRA BY GEORGE NICKAS and KEVIN PROESCHOLDT 19 Developing Wilderness Indicators on the INTERNATIONAL PERSPECTIVES White Mountain National Forest 42 Wilderness Conservation in a Biodiversity Hotspot BY DAVE NEELY BY RUSSELL A. MITTERMEIER, FRANK HAWKINS, SERGE RAJAOBELINA, and OLIVIER LANGRAND 22 Understanding the Cultural, Existence, and Bequest Values of Wilderness BY RUDY M. SCHUSTER, H. KEN CORDELL, and WILDERNESS DIGEST BRAD PHILLIPS 46 Announcements and Wilderness Calendar 26 8th World Wilderness Congress Generates Book Review Conservation Results 48 How Should America’s Wilderness Be Managed? BY VANCE G. MARTIN edited by Stuart A. Kallen REVIEWED BY JOHN SHULTIS FRONT COVER The magnificent El Carmen escaprment, one of the the “sky islands” of Coahuilo, Mexico. Photo by Patricio Robles Gil/Sierra Madre. INSET Ancient grain grinding site, Maderas del Carmen, Coahuilo, Mexico. Photo by Vance G. -

U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Prepared in cooperation with New Mexico Bureau of Mines and Mineral Resources 1997 MINERAL AND ENERGY RESOURCES OF THE MIMBRES RESOURCE AREA IN SOUTHWESTERN NEW MEXICO This report is preliminary and has not been reviewed for conformity with U.S. Geological Survey editorial standards or with the North American Stratigraphic Code. Any use of trade, product, or firm names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Cover: View looking south to the east side of the northeastern Organ Mountains near Augustin Pass, White Sands Missile Range, New Mexico. Town of White Sands in distance. (Photo by Susan Bartsch-Winkler, 1995.) MINERAL AND ENERGY RESOURCES OF THE MIMBRES RESOURCE AREA IN SOUTHWESTERN NEW MEXICO By SUSAN BARTSCH-WINKLER, Editor ____________________________________________________ U. S GEOLOGICAL SURVEY OPEN-FILE REPORT 97-521 U.S. Geological Survey Prepared in cooperation with New Mexico Bureau of Mines and Mineral Resources, Socorro U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR BRUCE BABBITT, Secretary U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Mark Shaefer, Interim Director For sale by U.S. Geological Survey, Information Service Center Box 25286, Federal Center Denver, CO 80225 Any use of trade, product, or firm names in this publication is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government MINERAL AND ENERGY RESOURCES OF THE MIMBRES RESOURCE AREA IN SOUTHWESTERN NEW MEXICO Susan Bartsch-Winkler, Editor Summary Mimbres Resource Area is within the Basin and Range physiographic province of southwestern New Mexico that includes generally north- to northwest-trending mountain ranges composed of uplifted, faulted, and intruded strata ranging in age from Precambrian to Recent. -

Description of the Silver City Quadrangle

DESCRIPTION OF THE SILVER CITY QUADRANGLE. By Sidney Paige. INTRODUCTION. The individual ranges, such as the Dragoon, Chiricahua, Pinalino, Mountain ranges of northern New Mexico. Its appearance is that of Galiuro, Santa Catalina, Tortilla, Final, Superstition, Ancha, and an upthrust of pre-Cambrian rocks, flanked on both sides by Paleozoic GENERAL RELATIONS OF THE QUADRANGLE. Mazatzal mountains, rarely exceed 50 miles in length or 8,000 rocks dipping away from the core. The extreme southwest corner of New Mexico embraces a part of a The Silver City quadrangle is bounded by meridians 108° feet in altitude. * * * Their general trend * * * near the Mexican border * * * becomes more nearly north and south, province foreign to the Territory as a whole that of the Arizona and 108° 30' and parallels 32° 30' and 33° and includes one- and the mountain zone as a whole coalesces with a belt of north-south desert ranges, numerous and small, trending northward and separated fourth of a "square degree" of the earth's surface, an area, in ranges which extends northward through New Mexico and borders by desert basins. That these ranges are post-Cretaceous admits of that latitude, of 1,003 square miles. It is in southwestern New the Plateau region on the east. little doubt. Probably they were outlined during the same early Mexico (see fig. 1) and almost wholly in Grant County, but Tertiary deformation that produced the ranges of the Rio Grande along the east half of its south side it includes a narrow strip The northward-trending ranges, such as the Peloncillo, valley. -

State No. Description Size in Cm Date Location

Maps State No. Description Size in cm Date Location National Forests in Alabama. Washington: ALABAMA AL-1 49x28 1989 Map Case US Dept. of Agriculture, Forest Service. Bankhead National Forest (Bankhead and Alabama AL-2 66x59 1981 Map Case Blackwater Districts). Washington: US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service. Side A : Coronado National Forest (Nogales A: 67x72 ARIZONA AZ-1 1984 Map Case Ranger District). Washington: US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service. B: 67x63 Side B : Coronado National Forest (Sierra Vista Ranger District). Side A : Coconino National Forest (North A:69x88 Arizona AZ-2 1976 Map Case Half). Washington: US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service. B:69x92 Side B : Coconino National Forest (South Half). Side A : Coronado National Forest (Sierra A:67x72 Arizona AZ-3 1976 Map Case Vista Ranger District. Washington: US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service. B:67x72 Side B : Coronado National Forest (Nogales Ranger District). Prescott National Forest. Washington: US Arizona AZ-4 28x28 1992 Map Case Department of Agriculture, Forest Service. Kaibab National Forest (North Unit). Arizona AZ-5 68x97 1967 Map Case Washington: US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service. Prescott National Forest- Granite Mountain Arizona AZ-6 67x48.5 1993 Map Case Wilderness. Washington: US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service. Side A : Prescott National Forest (East Half). A:111x75 Arizona AZ-7 1993 Map Case Washington: US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service. B:111x75 Side B : Prescott National Forest (West Half). Arizona AZ-8 Superstition Wilderness: Tonto National 55.5x78.5 1994 Map Case Forest. Washington: US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service. Arizona AZ-9 Kaibab National Forest, Gila and Salt River 80x96 1994 Map Case Meridian. -

Fiscal Impact Reports (Firs) Are Prepared by the Legislative Finance Committee (LFC) for Standing Finance Committees of the NM Legislature

Fiscal impact reports (FIRs) are prepared by the Legislative Finance Committee (LFC) for standing finance committees of the NM Legislature. The LFC does not assume responsibility for the accuracy of these reports if they are used for other purposes. Current FIRs (in HTML & Adobe PDF formats) are available on the NM Legislative Website (www.nmlegis.gov). Adobe PDF versions include all attachments, whereas HTML versions may not. Previously issued FIRs and attachments may be obtained from the LFC in Suite 101 of the State Capitol Building North. F I S C A L I M P A C T R E P O R T ORIGINAL DATE 02/07/13 SPONSOR Herrell/Martinez LAST UPDATED 02/18/13 HB 292 SHORT TITLE Transfer of Public Land Act SB ANALYST Weber REVENUE (dollars in thousands) Recurring Estimated Revenue Fund or Affected FY13 FY14 FY15 Nonrecurring (See Narrative) There (See Narrative) There may be additional may be additional Recurring General Fund revenue in future years. revenue in future years. (Parenthesis ( ) Indicate Revenue Decrease ESTIMATED ADDITIONAL OPERATING BUDGET IMPACT (dollars in thousands) 3 Year Recurring or Fund FY13 FY14 FY15 Total Cost Nonrecurring Affected General Total $100.0 $100.0 $200.0 Recurring Fund (Parenthesis ( ) Indicate Expenditure Decreases) Duplicate to SB 404 SOURCES OF INFORMATION LFC Files Responses Received From Administrative Office of the Courts (AOC) General Services Department (GSD) Economic Development Department (EDD) Department of Cultural Affairs (DCA) Energy, Minerals and Natural Resources Department (EMNRD) State Land Office (SLO) Department of Transportation (DOT) Department of Finance and Administration (DFA) House Bill 292 – Page 2 SUMMARY Synopsis of Bill House Bill 292 (HB 292) is the Transfer of Public Lands Act.