Wilderness Stewardship Performance: Guidance for Developing an Indigenous Fish and Wildlife Management Strategy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wildlife Management in the National Parks

wildlife management IN THE NATIONAL PARKS wildlife management IN IHE NATIONAL PARKS 1969 REPRINT FROM ADMINISTRATIVE POLICIES FOR NATURAL AREAS OF THE NATIONAL PARK SYSTEM U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR • NATIONAL PARK SERVICE For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington, D.C. 20402 - Price 15 cents WILDLIFE MANAGEMENT IN THE NATIONAL PARKS ADVISORY BOARD ON WILDLIFE MANAGEMENT, APPOINTED BY SECRETARY OF THE INTERIOR UDALL A. S. Leopold (Chairman), S. A. Cain, C. M. Cottam, I. N. Gabrielson, T. L. Kimball March 4, 1963 Historical In the Congressional Act of 1916 which created the National Park Service, preservation of native animal' life was clearly specified as one of the pur poses of the parks. A frequently quoted passage of the Act states "... which purpose is to conserve the scenery and the natural and historic objects and the wild life therein and to provide for the enjoyment of the same in such manner and by such means as will leave them unimpaired for the enjoy ment of future generations." In implementing this Act, the newly formed Park Service developed a philosophy of wildlife protection, which in that era was indeed the most obvious and immediate need in wildlife conservation. Thus the parks were established as refuges, the animal populations were protected from wildfire. For a time predators were controlled to protect the "good" ani mals from the "bad" ones, but this endeavor mercifully ceased in the 1930's. On the whole, there was little major change in the Park Service practice of wildlife management during the first 40 years of its existence. -

Wilderness Visitors and Recreation Impacts: Baseline Data Available for Twentieth Century Conditions

United States Department of Agriculture Wilderness Visitors and Forest Service Recreation Impacts: Baseline Rocky Mountain Research Station Data Available for Twentieth General Technical Report RMRS-GTR-117 Century Conditions September 2003 David N. Cole Vita Wright Abstract __________________________________________ Cole, David N.; Wright, Vita. 2003. Wilderness visitors and recreation impacts: baseline data available for twentieth century conditions. Gen. Tech. Rep. RMRS-GTR-117. Ogden, UT: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. 52 p. This report provides an assessment and compilation of recreation-related monitoring data sources across the National Wilderness Preservation System (NWPS). Telephone interviews with managers of all units of the NWPS and a literature search were conducted to locate studies that provide campsite impact data, trail impact data, and information about visitor characteristics. Of the 628 wildernesses that comprised the NWPS in January 2000, 51 percent had baseline campsite data, 9 percent had trail condition data and 24 percent had data on visitor characteristics. Wildernesses managed by the Forest Service and National Park Service were much more likely to have data than wildernesses managed by the Bureau of Land Management and Fish and Wildlife Service. Both unpublished data collected by the management agencies and data published in reports are included. Extensive appendices provide detailed information about available data for every study that we located. These have been organized by wilderness so that it is easy to locate all the information available for each wilderness in the NWPS. Keywords: campsite condition, monitoring, National Wilderness Preservation System, trail condition, visitor characteristics The Authors _______________________________________ David N. -

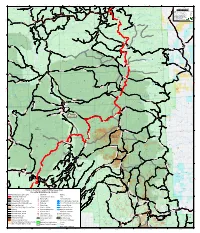

Trails in the Aldo Leopold Wilderness Area Recently Maintained & Cleared

l y R. 13 W. R. 12 W. R. 11 W. r l R. 10 W. t R. 9 W. R. 8 W. i r e t e 108°0'W m 107°45'W a v w o W a P S S le 11 Sawmill t Boundary Tank F t 6 40 10 i 1 6 Peak L 5 6 7M 10 11 9 1:63,360 0 0 8 9 12 8 8350 anyon Houghton Spring 4 7 40 7 5 7 T e C 1 in = 1 miles 11 12 4 71 7 7 0 Klin e C 10 0 C H 6 0 7 in Water anyon 8 9 6 a 4 0 Ranch P 4065A 7 Do 6 n 4 073Q (printed on 36" x 42" portrait layout) Houghton ag Z y 4 Well 12 Corduroy Corral y Doagy o 66 11 n 5 aska 10 Spr. Spr. Tank K Al 0 0.25 0.5 1 1.5 2 9 Corduroy Tank 1 1 14 13 7 2 15 5 0 4 Miles 5 Doagie Spr. 5 16 9 Beechnut Tank 4 0 17 6 13 18 n 8 14 yo 1 15 an Q C Deadman Tank 16 D Coordinate System: NAD 1983 UTM Zone 12NTransverse Mercator 3 3 3 17 0 r C 2 Sawmill 1 0 Rock 7 18 a Alamosa 13 w 6 1 Spr. Core 14 Attention: Reilly 6 Dirt Tank 8 15 0 Peak 14 Dev. Tank 3 Clay 4 15 59 16 Gila National Forest uses the most current n 0 16 S o 17 13 Santana 8163 1 17 3 y Doubleheader #2 Tank 18 Fence Tank Cr. -

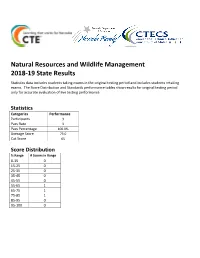

Natural Resources and Wildlife Management Statistics

Natural Resources and Wildlife Management 2018-19 State Results Statistics data includes students taking exams in the original testing period and includes students retaking exams. The Score Distribution and Standards performance tables show results for original testing period only for accurate evaluation of live testing performance. Statistics Categories Performance Participants 3 Pass Rate 3 Pass Percentage 100.0% Average Score 73.0 Cut Score 65 Score Distribution % Range # Scores in Range 0-15 0 15-25 0 25-35 0 35-45 0 45-55 0 55-65 1 65-75 1 75-85 1 85-95 0 95-100 0 Natural Resources and Wildlife Management 1) CONTENT STANDARD 1.0: EXPLORE NATURAL RESOURCE SCIENCE AND MANAGEMENT 75.93% 1) Performance Standard 1.1 : Investigate the Relationship Between Natural Resources and Society, Including Conflict Management 72.22% 1) 1.1.1 Define natural resource management 77.78% 3) 1.1.3 Describe human dependency and demands on natural resources 88.89% 4) 1.1.4 Explain natural resource conservation 66.67% 5) 1.1.5 Investigate the effects of multiple uses of natural resources (e.g., recreation, mining, agriculture, forestry, public lands grazing, etc.) 66.67% 6) 1.1.6 Analyze societal issues related to natural resource management 50% 2) Performance Standard 1.2 : Explain Interrelationships Between Natural Resources and Humans in Managing Natural Environments 86.67% 1) 1.2.1 Explain the effects and/or trade-off of population growth, greater energy consumption, and increased technology and development on natural resources and the environment 83.33% -

For-74: a Guide to Urban Habitat Conservation Planning

FOR-74 A Guide to Urban Habitat Conservation Planning Thomas G. Barnes, Extension Wildlife Specialist Lowell Adams, National Institute for Urban Wildlife entuckians value their forests and Kother natural resources for aes- Guidelines for Considering Wildlife in the Urban Development thetic, recreational, and economic Process significance, so over the past several Promote habitats that will have the food, cover, water, and living space that decades they have become increasingly all wildlife require by following these guidelines: concerned about the loss of wildlife • Before development, maximize open space and make an effort to protect the habitat and greenspace. Urban and most valuable wildlife habitat by placing buildings on less important portions suburban development is one of the of the site. Choosing cluster development, which is flexible, can help. leading causes of this loss: A recent • Provide water, and design stormwater control impoundments to benefit wildlife. study indicated that every day in • Use native plants that have value for wildlife as well as aesthetic appeal. Kentucky more than 100 acres of rural • Provide bird-feeding stations and nest boxes for cavity-nesting birds like land is being converted to urban house wrens and wood ducks. development. • Educate residents about wildlife conservation, using, for example, informa- Because concern for loss of tion packets or a nature trail through open space. greenspace is not new, we have for • Ensure a commitment to managing urban wildlife habitats. some time created attractive urban greenspace environments with our parks and backyards. These The publication can also be useful to A landscape is a large area com- greenspaces have been created not so the average homeowner in understand- posed of ecosystems (the plants, much for wildlife habitats as for people ing the complex issues involved in animals, other living organisms, and to enjoy, but the potential for wildlife landscape planning and wildlife their physical surroundings). -

Journal of Wilderness

INTERNATIONAL Journal of Wilderness DECEMBER 2005 VOLUME 11, NUMBER 3 FEATURES SCIENCE AND RESEARCH 3 Is Eastern Wilderness ”Real”? PERSPECTIVES FROM THE ALDO LEOPOLD WILDERNESS RESEARCH INSTITUTE BY REBECCA ORESKES 30 Social and Institutional Influences on SOUL OF THE WILDERNESS Wilderness Fire Stewardship 4 Florida Wilderness BY KATIE KNOTEK Working with Traditional Tools after a Hurricane BY SUSAN JENKINS 31 Wilderness In Whose Backyard? BY GARY T. GREEN, MICHAEL A. TARRANT, UTTIYO STEWARDSHIP RAYCHAUDHURI, and YANGJIAN ZHANG 7 A Truly National Wilderness Preservation System BY DOUGLAS W. SCOTT EDUCATION AND COMMUNICATION 39 Changes in the Aftermath of Natural Disasters 13 Keeping the Wild in Wilderness When Is Too Much Change Unacceptable to Visitors? Minimizing Nonconforming Uses in the National Wilderness Preservation System BY JOSEPH FLOOD and CRAIG COLISTRA BY GEORGE NICKAS and KEVIN PROESCHOLDT 19 Developing Wilderness Indicators on the INTERNATIONAL PERSPECTIVES White Mountain National Forest 42 Wilderness Conservation in a Biodiversity Hotspot BY DAVE NEELY BY RUSSELL A. MITTERMEIER, FRANK HAWKINS, SERGE RAJAOBELINA, and OLIVIER LANGRAND 22 Understanding the Cultural, Existence, and Bequest Values of Wilderness BY RUDY M. SCHUSTER, H. KEN CORDELL, and WILDERNESS DIGEST BRAD PHILLIPS 46 Announcements and Wilderness Calendar 26 8th World Wilderness Congress Generates Book Review Conservation Results 48 How Should America’s Wilderness Be Managed? BY VANCE G. MARTIN edited by Stuart A. Kallen REVIEWED BY JOHN SHULTIS FRONT COVER The magnificent El Carmen escaprment, one of the the “sky islands” of Coahuilo, Mexico. Photo by Patricio Robles Gil/Sierra Madre. INSET Ancient grain grinding site, Maderas del Carmen, Coahuilo, Mexico. Photo by Vance G. -

Biodiversity Conservation and Habitat Management

CONTENTS BIODIVERSITY CONSERVATION AND HABITAT MANAGEMENT Biodiversity Conservation and Habitat Management - Volume 1 No. of Pages: 458 ISBN: 978-1-905839-20-9 (eBook) ISBN: 978-1-84826-920-0 (Print Volume) Biodiversity Conservation and Habitat Management - Volume 2 No. of Pages: 428 ISBN: 978-1-905839-21-6 (eBook) ISBN: 978-1-84826-921-7 (Print Volume) For more information of e-book and Print Volume(s) order, please click here Or contact : [email protected] ©Encyclopedia of Life Support Systems (EOLSS) BIODIVERSITY CONSERVATION AND HABITAT MANAGEMENT CONTENTS Preface xv VOLUME I Biodiversity Conservation and Habitat Management : An Overview 1 Francesca Gherardi, Dipartimento di Biologia Animale e Genetica, Università di Firenze, Italy Claudia Corti, California Academy of Sciences, San Francisco CA, U.S.A. Manuela Gualtieri, Dipartimento di Scienze Zootecniche, Università di Firenze, Italy 1. Introduction: the amount of biological diversity 2. Diversity in ecosystems 2.1. African wildlife systems 2.2. Australian arid grazing systems 3. Measures of biodiversity 3.1. Species richness 3.2. Shortcuts to monitoring biodiversity: indicators, umbrellas, flagships, keystones, and functional groups 4. Biodiversity loss: the great extinction spasm 5. Causes of biodiversity loss: the “evil quartet” 5.1. Over-harvesting by humans 5.2. Habitat destruction and fragmentation 5.3. Impacts of introduced species 5.4. Chains of extinction 6. Why conserve biodiversity? 7. Conservation biology: the science of scarcity 8. Evaluating the status of a species: extinct until proven extant 9. What is to be done? Conservation options 9.1. Increasing our knowledge 9.2. Restore habitats and manage them 9.3. -

Wildlife Management Activities and Practices

WILDLIFE MANAGEMENT ACTIVITIES AND PRACTICES COMPREHENSIVE WILDLIFE MANAGEMENT PLANNING GUIDELINES for the Edwards Plateau and Cross Timbers & Prairies Ecological Regions Revised April 2010 The following Texas Parks & Wildlife Department staff have contributed to this document: Mike Krueger, Technical Guidance Biologist – Lampasas Mike Reagan, Technical Guidance Biologist -- Wimberley Jim Dillard, Technical Guidance Biologist -- Mineral Wells (Retired) Kirby Brown, Private Lands and Habitat Program Director (Retired) Linda Campbell, Program Director, Private Lands & Public Hunting Program--Austin Linda McMurry, Private Lands and Public Hunting Program Assistant -- Austin With Additional Contributions From: Kevin Schwausch, Private Lands Biologist -- Burnet Terry Turney, Rare Species Biologist--San Marcos Trey Carpenter, Manager, Granger Wildlife Management Area Dale Prochaska, Private Lands Biologist – Kerr Wildlife Management Area Nathan Rains, Private Lands Biologist – Cleburne TABLE OF CONTENTS Comprehensive Wildlife Management Planning Guidelines Edwards Plateau and Cross Timbers & Prairies Ecological Regions Introduction Specific Habitat Management Practices HABITAT CONTROL EROSION CONTROL PREDATOR CONTROL PROVIDING SUPPLEMENTAL WATER PROVIDING SUPPLEMENTAL FOOD PROVIDING SUPPLEMENTAL SHELTER CENSUS APPENDICES APPENDIX A: General Habitat Management Considerations, Recommendations, and Intensity Levels APPENDIX B: Determining Qualification for Wildlife Management Use APPENDIX C: Wildlife Management Plan Overview APPENDIX D: Livestock -

Forest Conservation and Management in The

Management in a Changing Climate Policy Challenges for Wildlife Abstract: Try as it might, wildlife management cannot make wild living things adapt to climate change. Management can, Mark L. Shaffer however, make adaptation more or less likely. Given that pol- Office of the Science Advisor, icy is a rule set for action, policy will play a critical role in U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service society’s efforts to help wildlife cope with the challenge of cli- mate change. To be effective, policy must provide clear goals and be based on a clear understanding of the problem it seeks to affect. The “National Fish, Wildlife, and Plants Climate Ad- aptation Strategy” provides seven major goals and numerous policy related actions for wildlife management in a period of climate change. The underlying themes of these recommenda- tions and the major challenges to their achievement are identi- fied and discussed. INTRODUCTION As one of the major biome types on Earth, forests are of fundamental importance to wildlife. (Note: the term “wildlife” when used alone is meant as short hand for all species living in an undomesticated state: both plant and animal.) From the standpoint of species diversity, the most diverse terrestrial habitats on Earth are the great tropical rainforests. From the standpoint of sheer stand- ing biomass, the great temperate rainforest of the Pacific Northwest may be unequalled. In terms of charismatic megafauna, which for most people are the face of wild- life, many signature North American species (e.g., deer, bear, elk, wolf, moose, cougar) are principally forest spe- cies. A large fraction of the lands American society has chosen to devote to conservation are forested lands. -

Tech Rev 03-1 for PDF.Qxd

The Relationship of Economic Growth to Wildlife Conservation Gross National Product Gross Time THE WILDLIFE SOCIETY Technical Review 03-1 2003 THE RELATIONSHIP OF ECONOMIC GROWTH TO WILDLIFE CONSERVATION The Wildlife Society Members of the Economic Growth Technical Review Committee David L. Trauger (Chair) Pamela R. Garrettson Natural Resources Program Division of Migratory Bird Management Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Northern Virginia Center 11500 American Holly Drive 7054 Haycock Road Laurel, MD 20708 Falls Church, VA 22043 Brian J. Kernohan Brian Czech Boise Cascade Corporation National Wildlife Refuge System 2010 South Curtis Circle U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Boise, ID 83705 4401 North Fairfax Drive, MS 670 Arlington, VA 22203 Craig A. Miller Human Dimensions Research Program Jon D. Erickson Illinois Natural History Survey School of Natural Resources 607 East Peabody Drive Aiken Center Champaign, IL 61820 University of Vermont Burlington, VT 05405 Edited by Krista E. M. Galley The Wildlife Society Technical Review 03-1 5410 Grosvenor Lane, Suite 200 March 2003 Bethesda, Maryland 20814 Foreword Presidents of The Wildlife Society occasionally appoint ad hoc committees to study and report on select conservation issues. The reports ordinarily appear as either a Technical Review or a Position Statement. Review papers present technical information and the views of the appointed committee members, but not necessarily the views of their employers. Position statements are based on the review papers, and the preliminary versions are published in The Wildlifer for comment by Society members. Following the comment period, revision, and Council's approval, the statements are published as official positions of The Wildlife Society. -

Technical Review 12-04 December 2012

The North American Model of Wildlife Conservation Technical Review 12-04 December 2012 1 The North American Model of Wildlife Conservation The Wildlife Society and The Boone and Crockett Club Technical Review 12-04 - December 2012 Citation Organ, J.F., V. Geist, S.P. Mahoney, S. Williams, P.R. Krausman, G.R. Batcheller, T.A. Decker, R. Carmichael, P. Nanjappa, R. Regan, R.A. Medellin, R. Cantu, R.E. McCabe, S. Craven, G.M. Vecellio, and D.J. Decker. 2012. The North American Model of Wildlife Conservation. The Wildlife Society Technical Review 12-04. The Wildlife Society, Bethesda, Maryland, USA. Series Edited by Theodore A. Bookhout Copy Edit and Design Terra Rentz (AWB®), Managing Editor, The Wildlife Society Lisa Moore, Associate Editor, The Wildlife Society Maja Smith, Graphic Designer, MajaDesign, Inc. Cover Images Front cover, clockwise from upper left: 1) Canada lynx (Lynx canadensis) kittens removed from den for marking and data collection as part of a long-term research study. Credit: John F. Organ; 2) A mixed flock of ducks and geese fly from a wetland area. Credit: Steve Hillebrand/USFWS; 3) A researcher attaches a radio transmitter to a short-horned lizard (Phrynosoma hernandesi) in Colorado’s Pawnee National Grassland. Credit: Laura Martin; 4) Rifle hunter Ron Jolly admires a mature white-tailed buck harvested by his wife on the family’s farm in Alabama. Credit: Tes Randle Jolly; 5) Caribou running along a northern peninsula of Newfoundland are part of a herd compositional survey. Credit: John F. Organ; 6) Wildlife veterinarian Lisa Wolfe assesses a captive mule deer during studies of density dependence in Colorado. -

Fiscal Impact Reports (Firs) Are Prepared by the Legislative Finance Committee (LFC) for Standing Finance Committees of the NM Legislature

Fiscal impact reports (FIRs) are prepared by the Legislative Finance Committee (LFC) for standing finance committees of the NM Legislature. The LFC does not assume responsibility for the accuracy of these reports if they are used for other purposes. Current FIRs (in HTML & Adobe PDF formats) are available on the NM Legislative Website (www.nmlegis.gov). Adobe PDF versions include all attachments, whereas HTML versions may not. Previously issued FIRs and attachments may be obtained from the LFC in Suite 101 of the State Capitol Building North. F I S C A L I M P A C T R E P O R T ORIGINAL DATE 02/07/13 SPONSOR Herrell/Martinez LAST UPDATED 02/18/13 HB 292 SHORT TITLE Transfer of Public Land Act SB ANALYST Weber REVENUE (dollars in thousands) Recurring Estimated Revenue Fund or Affected FY13 FY14 FY15 Nonrecurring (See Narrative) There (See Narrative) There may be additional may be additional Recurring General Fund revenue in future years. revenue in future years. (Parenthesis ( ) Indicate Revenue Decrease ESTIMATED ADDITIONAL OPERATING BUDGET IMPACT (dollars in thousands) 3 Year Recurring or Fund FY13 FY14 FY15 Total Cost Nonrecurring Affected General Total $100.0 $100.0 $200.0 Recurring Fund (Parenthesis ( ) Indicate Expenditure Decreases) Duplicate to SB 404 SOURCES OF INFORMATION LFC Files Responses Received From Administrative Office of the Courts (AOC) General Services Department (GSD) Economic Development Department (EDD) Department of Cultural Affairs (DCA) Energy, Minerals and Natural Resources Department (EMNRD) State Land Office (SLO) Department of Transportation (DOT) Department of Finance and Administration (DFA) House Bill 292 – Page 2 SUMMARY Synopsis of Bill House Bill 292 (HB 292) is the Transfer of Public Lands Act.