Chapter 13: Clapham Common to Lavender Hill

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

St Mary's Hall, St Alphonsus Road, Clapham, London Sw4

ST MARY’S HALL, ST ALPHONSUS ROAD, CLAPHAM, LONDON SW4 7AP CHURCH HALL DEVELOPMENT OPPORTUNITY IN A HIGHLY DESIRABLE LOCATION geraldeve.com 1 ST MARY’S HALL, ST ALPHONSUS ROAD, CLAPHAM, LONDON SW4 7AP The Opportunity • Prominent three-storey detached former church hall (F1 Use Class) • Situated close-by to Clapham Common Underground Station and Clapham High Street • Double-height worship hall with ancillary facilities and self-contained three bedroom flat • Gross internal floor area of approximately 702 sq m (7,560 sq ft) on a site of circa 0.17 acre • Suitable for a variety of community uses, with scope for redevelopment to residential, subject to planning permission • The vendors are seeking a development partner to obtain planning permission and build a new Parish facility of approximately 177 sq m (1,650 sq ft GIA) on the site to replace the existing facility as part of any redevelopment of the site • Alternatively, the vendors would consider sharing the use of the existing hall with an owner occupier, if a new Parish facility could be provided as part of any conversion • Offered leasehold for a minimum term of 150 years ST MARY’S HALL, ST ALPHONSUS ROAD, CLAPHAM, LONDON SW4 7AP 3 Alperton King’s Cross St Pancras Location Greenford Paddington Euston Angel Euston Old Street The property is conveniently located on St Alphonsus Baker Street Square Farringdon Road within 150 metres of Clapham Common Underground Bayswater Aldgate Station and Clapham High Street in a predominantly Oxford Bond Street East Circus Moorgate Liverpool Street residential area in the London Borough of Lambeth. -

Download Network

Milton Keynes, London Birmingham and the North Victoria Watford Junction London Brentford Waterloo Syon Lane Windsor & Shepherd’s Bush Eton Riverside Isleworth Hounslow Kew Bridge Kensington (Olympia) Datchet Heathrow Chiswick Vauxhall Airport Virginia Water Sunnymeads Egham Barnes Bridge Queenstown Wraysbury Road Longcross Sunningdale Whitton TwickenhamSt. MargaretsRichmondNorth Sheen BarnesPutneyWandsworthTown Clapham Junction Staines Ashford Feltham Mortlake Wimbledon Martins Heron Strawberry Earlsfield Ascot Hill Croydon Tramlink Raynes Park Bracknell Winnersh Triangle Wokingham SheppertonUpper HallifordSunbury Kempton HamptonPark Fulwell Teddington Hampton KingstonWick Norbiton New Oxford, Birmingham Winnersh and the North Hampton Court Malden Thames Ditton Berrylands Chertsey Surbiton Malden Motspur Reading to Gatwick Airport Chessington Earley Bagshot Esher TolworthManor Park Hersham Crowthorne Addlestone Walton-on- Bath, Bristol, South Wales Reading Thames North and the West Country Camberley Hinchley Worcester Beckenham Oldfield Park Wood Park Junction South Wales, Keynsham Trowbridge Byfleet & Bradford- Westbury Brookwood Birmingham Bath Spaon-Avon Newbury Sandhurst New Haw Weybridge Stoneleigh and the North Reading West Frimley Elmers End Claygate Farnborough Chessington Ewell West Byfleet South New Bristol Mortimer Blackwater West Woking West East Addington Temple Meads Bramley (Main) Oxshott Croydon Croydon Frome Epsom Taunton, Farnborough North Exeter and the Warminster Worplesdon West Country Bristol Airport Bruton Templecombe -

Buses from Battersea Park

Buses from Battersea Park 452 Kensal Rise Ladbroke Grove Ladbroke Grove Notting Hill Gate High Street Kensington St Charles Square 344 Kensington Gore Marble Arch CITY OF Liverpool Street LADBROKE Royal Albert Hall 137 GROVE N137 LONDON Hyde Park Corner Aldwych Monument Knightsbridge for Covent Garden N44 Whitehall Victoria Street Horse Guards Parade Westminster City Hall Trafalgar Square Route fi nder Sloane Street Pont Street for Charing Cross Southwark Bridge Road Southwark Street 44 Victoria Street Day buses including 24-hour services Westminster Cathedral Sloane Square Victoria Elephant & Castle Bus route Towards Bus stops Lower Sloane Street Buckingham Palace Road Sloane Square Eccleston Bridge Tooting Lambeth Road 44 Victoria Coach Station CHELSEA Imperial War Museum Victoria Lower Sloane Street Royal Hospital Road Ebury Bridge Road Albert Embankment Lambeth Bridge 137 Marble Arch Albert Embankment Chelsea Bridge Road Prince Consort House Lister Hospital Streatham Hill 156 Albert Embankment Vauxhall Cross Vauxhall River Thames 156 Vauxhall Wimbledon Queenstown Road Nine Elms Lane VAUXHALL 24 hour Chelsea Bridge Wandsworth Road 344 service Clapham Junction Nine Elms Lane Liverpool Street CA Q Battersea Power Elm Quay Court R UE R Station (Disused) IA G EN Battersea Park Road E Kensal Rise D ST Cringle Street 452 R I OWN V E Battersea Park Road Wandsworth Road E A Sleaford Street XXX ROAD S T Battersea Gas Works Dogs and Cats Home D A Night buses O H F R T PRINCE O U DRIVE H O WALES A S K V Bus route Towards Bus stops E R E IV A L R Battersea P O D C E E A K G Park T A RIV QUEENST E E I D S R RR S R The yellow tinted area includes every Aldwych A E N44 C T TLOCKI bus stop up to about one-and-a-half F WALE BA miles from Battersea Park. -

1838 C London4 For

04 SPRING 2004 Changing London AN HISTORIC CITY FOR A MODERN WORLD ‘Successive generations of Londoners will judge us not only on how well we R IS FOR RESTORATION – conserve the past, but on AND MUCH MORE how well we build for Restoration is so much more than simply looking the future.’ to the past, as it can also bring fresh new life and exciting transformation. Philip Davies London Region Director, English Heritage Restoration of the historic environment is just as diverse. In this edition of Changing London,snapshots of projects involving English Heritage and its partners from across the capital demonstrate that ‘R’ is not just for ‘restoration’ but for ‘reinvention’ and ‘renewal’. Old buildings and places can be given back their dignity. Others are finding a new lease of life with completely different uses. Still more are being renewed by a combination of both reinvention and restoration. These projects are just a tiny proportion of the work that English Heritage is supporting and assisting across London to create a genuinely sustainable future for both buildings and places. ‘R’ truly stands for much more than just restoration. CONTENTS 4/5 6/7 2/3 R is for Restoration: Specialist R is for Renewal: Regenerating R is for Reinvention: skills nurture special places. London’s historic places. Unexpected new life for historic buildings. 04 SPRING 2004 R IS FOR REINVENTION Finding new uses for historic buildings can be fraught with Below, Roger Mascall charts the transformation of a difficulties. Balancing the need to preserve the character and redundant cinema into a vibrant new gym. -

No 424, February 2020

The Clapham Society Newsletter Issue 424 February 2020 We meet at Omnibus Theatre, 1 Clapham Common North Side, SW4 0QW. Our guests normally speak for about 45 minutes, followed by around 15 minutes for questions and discussion. The bar is open before and after. Meetings are free and open to non-members, who are strongly urged to make a donation. Please arrive in good time before the start to avoid disappointment. Gems of the London Underground Monday 17 February On 18 November, we were treated to a talk about the London Underground network, Sharing your personal data in the the oldest in the world, by architectural historian Edmund Bird, Heritage Manager of Health and Care System. Dr Jack Transport for London. He has just signed off on a project to record every heritage asset Barker, consultant physician at King’s and item of architectural and historic interest at its 270 stations. With photographs and College Hospital, is also the Chief back stories, he took us on a Tube ride like no other. Clinical Information Officer for the six One of his key tools is the London Underground Station Design Idiom, which boroughs of southeast London. He is groups the stations into 20 subsets, based on their era or architectural genre, and the driving force behind attempting to specifies the authentic historic colour schemes, tile/masonry repairs, etc, to be used improve the effectiveness and efficiency for station refurbishments. Another important tool is the London Underground Station of local health and care through the use of Heritage Register, which is an inventory of everything from signs, clocks, station information technology, and he will tell us benches, ticket offices and tiling to station histories. -

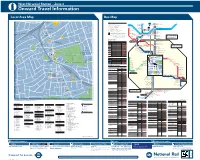

Local Area Map Bus Map

West Norwood Station – Zone 3 i Onward Travel Information Local Area Map Bus Map 64 145 P A P G E A L A 99 PALACE ROAD 1 O 59 C E R Tulse Hill D CARSON ROAD O 1 A D 123 A 12 U 80 G R O N ROSENDALE ROAD Key 136 V E 18 The Elmgreen E 92 School V N68 68 Euston A 111 2 Day buses in black Marylebone 2 Tottenham R ELMCOURT ROAD E DALMORE ROAD N68 Night buses in blue Court Road X68 Russell Square for British Museum T 1 Gloucester Place S 2 TULSEMERE ROAD 2 Ø— KINGSMEAD ROAD 1 218 415 A Connections with London Underground C for Baker Street 121 120 N LAVENGRO ROAD River Thames Holborn 72 u Connections with London Overground A 51 44 33 L Marble Arch KINFAUNS ROAD 2 HEXHAM ROAD NORTHSTEAD ROAD R Connections with National Rail N2 Aldwych for Covent Garden 11 114 PENRITH PLACE ARDLUI ROAD 2 ELMWORTH GROVE 322 and London Transport Museum 18 Hyde Park Corner Trafalgar Square LEIGHAM VALE The Salvation h Connections with Tramlink N Orford Court VE RO Army 56 H G Clapham Common for Buckingham Palace for Charing Cross OR T River Thames O ELMW Connections with river boats 1 Â Old Town Westminster ELMWORTH GROVE R 100 EASTMEARN ROAD Waterloo Bridge for Southbank Centre, W x Mondays to Fridays morning peaks only, limited stop 14 IMAX Cinema and London Eye 48 KINGSMEAD ROAD 1 HARPENDEN ROAD 61 31 O 68 Clapham Common Victoria 13 93 w Mondays to Fridays evening peaks only Waterloo O E 51 59 U L West Norwood U 40 V 1 D E N R 43 4 S 445 Fire Station E Vauxhall Bridge Road T 1 St GeorgeÕs Circus O V D O V E A N A G R 14 E R A R O T H for Pimlico 12 1 TOWTON ROAD O R 196 R O N 1 L M W Clapham North O O S T E Red discs show the bus stop you need for your chosen bus A R M I D E I D for Clapham High Street D A T 37 service. -

The Clapham Sect : an Investigation Into the Effects of Deep Faith in a Personal God on a Change Effort

University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository Honors Theses Student Research 2000 The lC apham Sect : an investigation into the effects of deep faith in a personal God on a change effort Victoria Marple Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.richmond.edu/honors-theses Part of the Leadership Studies Commons Recommended Citation Marple, Victoria, "The lC apham Sect : an investigation into the effects of deep faith in a personal God on a change effort" (2000). Honors Theses. 1286. https://scholarship.richmond.edu/honors-theses/1286 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. UNIVERSITYOFRICHMOND UBRARIES iIll IllI Ill Ill II IllII IIIII IIll II IllIll I Ill I Ill 111111111111111 ! 3 3082 00741 4278 The Clapham Sect: · An Investigation into the Effects of a Deep Faith in a Personal God on a Change Effort By Victoria Marple Senior Project Jepson School of Leadership Studies University of Richmond Richmond, Virginia May,2000 The Clapham Sect: An Investigation into the Effects of a Deep Faith in a Personal God on a Change Effort Senior Project By: Victoria Marple Jepson School of Leadership Studies University of Richmond Richmond, VA 2 INTRODUCTION Throughout history, Christians, those who have followed the ways and teachings of Christ, have sought to ameliorate a myriad of inequalities including poverty, poor treatment of people with physical disabilities and slavery. For Christians, these efforts are directly taken from the conduct of Jesus Christ between 30-33 ad. -

Winterville 2021, Clapham Common

WINTERVILLE 2021, CLAPHAM COMMON • Event Dates: 18th November – 23rd December 2021 • Venue: Clapham Common Funfair Site • Maximum Capacity: 4,999 persons • Age Restrictions: The event is open to all ages WINTERVILLE 2021 EVENT OVERVIEW • Winterville is a community taking place on the hardstanding funfair site to the West side of Clapham Common with a maximum capacity of 4,999, • The event showcases music, films, plays, interactive games, food, drink and markets • Free entry and discounts for neighbours • Job opportunities for the local community, with roles including: o Performers o Traders o Sound & Lighting engineers o Event Staff o Construction An alternative destination for the festive season - a community and family focused friendly cultural hub Maximum 4,999 patrons on site at bringing together great any point entertainment, food and drink. The event will Family friendly live cater for those entertainment, immersive with accessible theatre shows, children’s needs film screenings, ice curling, funfair rides, crazy golf and more. Free to enter at all times for children under 16. A small entry fee for adults will be charged at Free tickets and peak times, likely Fri nights, discounts for Saturdays & Sundays. Wandsworth Residents WINTERVILLE 2021 CONTENT • Spiegeltent Entertainment Spaces • Children’s Performances • Enchanted Winter Themed Cinema • Ice Curling • Crazy Golf • Fairground • Indoor heated food court • Independent Craft Market • Brew Camp Real Ale Bar • Themed Bars • Axe Throwing • Tejo Game WINTERVILLE 2018 COMMUNITY BENEFITS OVERVIEW Park Investment Levy • In 2018, £70,000 was levied from Winterville for the Clapham Common Park Investment Levy. This money was spent on projects such as: more bins, replacing perimeter fencing, restoring the paddling pool, upgrading Battersea Rise Playground. -

Buses from Upper Norwood (Beulah Hill) X68 Russell Square Tottenham for British Museum Court Road N68 Holborn Route Finder Aldwych for Covent Garden Day Buses

Buses from Upper Norwood (Beulah Hill) X68 Russell Square Tottenham for British Museum Court Road N68 Holborn Route finder Aldwych for Covent Garden Day buses Bus route Towards Bus stops River Thames Elephant & Castle Ǩ ǫ ǭ Ǯ Waterloo Westwood Hill Lower Sydenham 196 VAUXHALL for IMAX Theatre, London Eye & South Bank Arts Centre Sydenham Bell Green 450 Norwood Junction ɧ ɨ ɩ ɰ Sydenham Lower Sydenham Vauxhall 196 468 Sainsburys Elephant & Castle Fountain Drive Kennington 249 Anerley ɧ ɨ ɩ ɰ Lansdowne Way Lane Route X68 runs non-stop between West Norwood and Walworth Road Waterloo during the Monday-Friday morning peak only. Kingswood Drive SYDENHAM Clapham Common Ǩ ǫ ǭ Ǯ College Road Stockwell Passengers cannot alight before Waterloo. Ā ā 249 Camberwell Green 450 Lower Sydenham Clapham Common Stockwell Green Kingswood Drive Old Town Bowen Drive West Croydon ˓ ˗ Brixton Effra Denmark Hill Road Kings College Hospital Dulwich Wood Park Kingswood Drive 468 Elephant & Castle Ǩ ǫ ǭ Ǯ Brixton Herne Hill Clapham Common South BRIXTON Lambeth Town Hall Dulwich Wood Park CRYSTAL South Croydon ɧ ɨ ɩ ɰ Norwood Road College Road Deronda Road HERNE PALACE Clapham South Norwood Road Crystal Palace Parade HILL College Road Night buses Thurlow Park Road Anerley Road Thicket Road BALHAM Tulse Hill Crystal Palace Anerley Road Bus route Towards Bus stops TULSE Parade Ridsdale Road Balham Anerley Road Norwood Road Hamlet Road Old Coulsdon ɧ ɨ ɩ ɰ HILL Lancaster Avenue N68 Norwood Road Crystal Palace for National Sports Centre Anerley Tottenham Court Road Ǩ ǫ -

Brixton and Clapham Park PCN Patient Group Meeting

Brixton and Clapham Park PCN Patient group meeting Notes of meeting held on Zoom 14 April 2021. Present: Nicola Kingston (Chair), Dr Jennie Parker (Chair of PCN, Hetherington), Dave Ball, Ros Borley, Pippa Cardale, Jenny Cobley, Mr & Mrs Day, Craig Givens, Lucy Ismail, Christine Jacobs, Ernestine Montgomerie, Chris Newman (Managing Partner, Clapham Park), Rebecca McNair, Liz Dunbar, Rev Funke Ogbede, Esigbemi Osoba, Martin Pratt, David Ritchie, Maureen Simpson, Sara Taffinder, Peter Woodward. Apologies: Dr Andrew Boyd (Clapham Park), Barbara Wilson, Paulina Tamborrel Signoret (Citizens UK Lambeth). 1. Welcome and introductions. Nicola welcomed everyone and introductions were made. Jenny Cobley agreed to take the notes. 2. Update on the Covid Vaccination programme and surge testing for Covid variants. Dr Jennie Parker reported on the vaccination programme, which is going smoothly at Hetherington Group Practice (HGP), where they now have cover over the waiting area outside. The final delivery of Pfizer vaccine for second doses was due this weekend . The Oxford Astra Zeneca (OAZ) vaccine would also be available for second doses next week, and for those in groups 1-9 who have not yet had the vaccine and for those 45+ years. Chris Newman is organising the vaccination team, they are training more staff, St John’s ambulance personnel and medical students as vaccinators, as the vaccination programme is likely to continue for some months. There is always a lead GP on duty. An increase in uptake among ethnic minority groups has been seen in our area. Uptake of vaccines is 77% overall, with 89% among white, 81% Asian and 65% black patients. -

London Underground Route

Epping London Theydon Bois Underground Route map Debden Chesham LastUpdate Jan.20.2019 Watford Junction Cheshunt Loughton Amersham Chalfont & Latimer Watford High Street Cockfosters Enfield Town Theobalds Grove Watford Chorleywood Turkey Street Buckhurst Hill Bushey Oakwood Bush Hill Park Roding Valley Chingwell Rickmansworth Croxley High Barnet Southbury Carpenders Park Southgate Totteridge & Whetstone Woodford Grange Hill Moor Park Hatch End Arnos Grove Edmonton Green West Ruislip Woodside Park Chingford Hainault Shenfield Northwood Headstone Lane Mill Hill East Bounds Green Silver Street South Woodford Fairlop Ruislip Stanmore Edgware West Finchley Brentwood Northwood Hills Wood Green White Hart Lane Highams Park Barkingside Harrow & Wealdstone Snaresbrook Harold Wood Canons Park Burnt Oak Newbury Park Uxbridge Ickenham Ruislip Manor Pinner Finchley Central Turnpike Lane Bruce Grove Gidea Park Wanstead Gants Hill Kenton Queensbury Colindale South Tottenham Wood Street Romford Eastcote North Harrow East Finchley Redbridge Northwick Park Preston Road Kingsbury Hendon Central Harringay Green Lanes Blackhorse Road Chadwell Heath Ruislip Gardens Rayners Lane Highgate Crouch Hill Seven Sisters Walthamstow Central Goodmayes West Harrow Harrow on the Hill Brent Cross Manor House Tottenham Hale Leytonstone Emerson Park South Kenton Archway Walthamstow Queen’s Road Seven Kings Wembley Park Golders Green Upper Holloway Stamford Hill Gospel Oak Leytonstone High Ilford North Wembley Hampstead Finsbury Park St. James Street Road Wanstead Park Hampstead -

No 336, April 2011

The Clapham Society Newsletter Issue 336 April 2011 A VISIT TO WANDSWORTH MUSEUM Camping on Clapham Common? Lambeth Council have lifted their self-imposed restrictions on Wednesday 20 April the size, length and frequency of events on Clapham Common. This meeting will be at Wandsworth Museum, 38 West The impact of this change in policy is about to be felt. Hill, SW18 1RZ. The 37 bus goes direct from Clapham The first event, which is causing great concern locally, is Common to Wandsworth Museum. Routes 337 and 170 scheduled to take place from 28 April to 1 May. This will involve from Clapham Junction also go past the Museum. There is a screening of the royal wedding and ‘family’ events. There free parking in nearby streets after 6.30 pm. Admission to will be a campsite with 1800 tents to accommodate up to 4000 the museum is FREE on this evening. people, and food outlets on site. For full details of the event go to www.camproyale.co,uk. Surprisingly, there was no consultation The Museum café, which sells delicious cakes and snacks as about this event with either the Clapham Common Management well as coffee, tea, soft drinks and wine will be open from Advisory Committee (CCMAC) or the Clapham Common Ward 7.30 pm. At 8 pm the Director of the Museum, Ken Barbour, Councillors. will tell us about the history and formation of the museum News of the proposed event led to a Press Statement from and introduce the permanent collection which tells the story Lambeth Council to the effect that final approval had not been of Wandsworth from 25,000 years ago to the present.