The Clapham Sect : an Investigation Into the Effects of Deep Faith in a Personal God on a Change Effort

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

St Mary's Hall, St Alphonsus Road, Clapham, London Sw4

ST MARY’S HALL, ST ALPHONSUS ROAD, CLAPHAM, LONDON SW4 7AP CHURCH HALL DEVELOPMENT OPPORTUNITY IN A HIGHLY DESIRABLE LOCATION geraldeve.com 1 ST MARY’S HALL, ST ALPHONSUS ROAD, CLAPHAM, LONDON SW4 7AP The Opportunity • Prominent three-storey detached former church hall (F1 Use Class) • Situated close-by to Clapham Common Underground Station and Clapham High Street • Double-height worship hall with ancillary facilities and self-contained three bedroom flat • Gross internal floor area of approximately 702 sq m (7,560 sq ft) on a site of circa 0.17 acre • Suitable for a variety of community uses, with scope for redevelopment to residential, subject to planning permission • The vendors are seeking a development partner to obtain planning permission and build a new Parish facility of approximately 177 sq m (1,650 sq ft GIA) on the site to replace the existing facility as part of any redevelopment of the site • Alternatively, the vendors would consider sharing the use of the existing hall with an owner occupier, if a new Parish facility could be provided as part of any conversion • Offered leasehold for a minimum term of 150 years ST MARY’S HALL, ST ALPHONSUS ROAD, CLAPHAM, LONDON SW4 7AP 3 Alperton King’s Cross St Pancras Location Greenford Paddington Euston Angel Euston Old Street The property is conveniently located on St Alphonsus Baker Street Square Farringdon Road within 150 metres of Clapham Common Underground Bayswater Aldgate Station and Clapham High Street in a predominantly Oxford Bond Street East Circus Moorgate Liverpool Street residential area in the London Borough of Lambeth. -

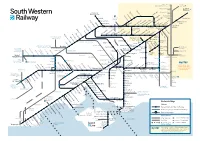

Download Network

Milton Keynes, London Birmingham and the North Victoria Watford Junction London Brentford Waterloo Syon Lane Windsor & Shepherd’s Bush Eton Riverside Isleworth Hounslow Kew Bridge Kensington (Olympia) Datchet Heathrow Chiswick Vauxhall Airport Virginia Water Sunnymeads Egham Barnes Bridge Queenstown Wraysbury Road Longcross Sunningdale Whitton TwickenhamSt. MargaretsRichmondNorth Sheen BarnesPutneyWandsworthTown Clapham Junction Staines Ashford Feltham Mortlake Wimbledon Martins Heron Strawberry Earlsfield Ascot Hill Croydon Tramlink Raynes Park Bracknell Winnersh Triangle Wokingham SheppertonUpper HallifordSunbury Kempton HamptonPark Fulwell Teddington Hampton KingstonWick Norbiton New Oxford, Birmingham Winnersh and the North Hampton Court Malden Thames Ditton Berrylands Chertsey Surbiton Malden Motspur Reading to Gatwick Airport Chessington Earley Bagshot Esher TolworthManor Park Hersham Crowthorne Addlestone Walton-on- Bath, Bristol, South Wales Reading Thames North and the West Country Camberley Hinchley Worcester Beckenham Oldfield Park Wood Park Junction South Wales, Keynsham Trowbridge Byfleet & Bradford- Westbury Brookwood Birmingham Bath Spaon-Avon Newbury Sandhurst New Haw Weybridge Stoneleigh and the North Reading West Frimley Elmers End Claygate Farnborough Chessington Ewell West Byfleet South New Bristol Mortimer Blackwater West Woking West East Addington Temple Meads Bramley (Main) Oxshott Croydon Croydon Frome Epsom Taunton, Farnborough North Exeter and the Warminster Worplesdon West Country Bristol Airport Bruton Templecombe -

William Wilberforce: Triumph Over Britain’S Slave Trade

William Wilberforce: Triumph Over Britain’s Slave Trade Abigail Rahn Senior Division Historical Paper Words: 2499 Rahn 1 History has shown that the road to societal change is often paved with hardship and sorrow. The fight to end the British slave trade was a poignant example of the struggles to reach that change. The British slave trade thrived for over two centuries and was responsible for transporting 3.4 million slaves, mainly to Spanish, Portuguese, and British colonies.1 This horrific institution was permeated with misery, corruption, and cruelty. The conditions on the ships were abhorrent. The male captives were shackled together below deck, unable to move, and forced to lie in their own filth.2 The women were allowed some mobility and stayed on deck but were exposed to sexual harassment.3 Yet the appalling trade was “as accepted as birth and marriage and death.”4 It was not until William Wilberforce decided to combat slavery within Parliament that slaves had true hope of freedom. William Wilberforce’s campaign against the British slave trade, beginning in 1789, was a seemingly-endless battle against the trade’s relentless supporters. His faith propelled him through many personal tragedies for nearly two decades before he finally triumphed over the horrific trade. Because of Wilberforce’s faith-fueled determination, the slave trade was eradicated in the most powerful empire in the world. After the trade was abolished, Wilberforce fought for emancipation of all slaves in the British empire. He died just days after the House of Commons passed the act to free all slaves, an act that owed its existence to Wilberforce’s relentless fight against the slave trade.5 1Clarkson, Thomas. -

Buses from Battersea Park

Buses from Battersea Park 452 Kensal Rise Ladbroke Grove Ladbroke Grove Notting Hill Gate High Street Kensington St Charles Square 344 Kensington Gore Marble Arch CITY OF Liverpool Street LADBROKE Royal Albert Hall 137 GROVE N137 LONDON Hyde Park Corner Aldwych Monument Knightsbridge for Covent Garden N44 Whitehall Victoria Street Horse Guards Parade Westminster City Hall Trafalgar Square Route fi nder Sloane Street Pont Street for Charing Cross Southwark Bridge Road Southwark Street 44 Victoria Street Day buses including 24-hour services Westminster Cathedral Sloane Square Victoria Elephant & Castle Bus route Towards Bus stops Lower Sloane Street Buckingham Palace Road Sloane Square Eccleston Bridge Tooting Lambeth Road 44 Victoria Coach Station CHELSEA Imperial War Museum Victoria Lower Sloane Street Royal Hospital Road Ebury Bridge Road Albert Embankment Lambeth Bridge 137 Marble Arch Albert Embankment Chelsea Bridge Road Prince Consort House Lister Hospital Streatham Hill 156 Albert Embankment Vauxhall Cross Vauxhall River Thames 156 Vauxhall Wimbledon Queenstown Road Nine Elms Lane VAUXHALL 24 hour Chelsea Bridge Wandsworth Road 344 service Clapham Junction Nine Elms Lane Liverpool Street CA Q Battersea Power Elm Quay Court R UE R Station (Disused) IA G EN Battersea Park Road E Kensal Rise D ST Cringle Street 452 R I OWN V E Battersea Park Road Wandsworth Road E A Sleaford Street XXX ROAD S T Battersea Gas Works Dogs and Cats Home D A Night buses O H F R T PRINCE O U DRIVE H O WALES A S K V Bus route Towards Bus stops E R E IV A L R Battersea P O D C E E A K G Park T A RIV QUEENST E E I D S R RR S R The yellow tinted area includes every Aldwych A E N44 C T TLOCKI bus stop up to about one-and-a-half F WALE BA miles from Battersea Park. -

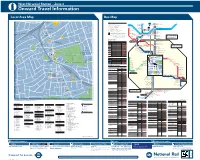

Local Area Map Bus Map

West Norwood Station – Zone 3 i Onward Travel Information Local Area Map Bus Map 64 145 P A P G E A L A 99 PALACE ROAD 1 O 59 C E R Tulse Hill D CARSON ROAD O 1 A D 123 A 12 U 80 G R O N ROSENDALE ROAD Key 136 V E 18 The Elmgreen E 92 School V N68 68 Euston A 111 2 Day buses in black Marylebone 2 Tottenham R ELMCOURT ROAD E DALMORE ROAD N68 Night buses in blue Court Road X68 Russell Square for British Museum T 1 Gloucester Place S 2 TULSEMERE ROAD 2 Ø— KINGSMEAD ROAD 1 218 415 A Connections with London Underground C for Baker Street 121 120 N LAVENGRO ROAD River Thames Holborn 72 u Connections with London Overground A 51 44 33 L Marble Arch KINFAUNS ROAD 2 HEXHAM ROAD NORTHSTEAD ROAD R Connections with National Rail N2 Aldwych for Covent Garden 11 114 PENRITH PLACE ARDLUI ROAD 2 ELMWORTH GROVE 322 and London Transport Museum 18 Hyde Park Corner Trafalgar Square LEIGHAM VALE The Salvation h Connections with Tramlink N Orford Court VE RO Army 56 H G Clapham Common for Buckingham Palace for Charing Cross OR T River Thames O ELMW Connections with river boats 1 Â Old Town Westminster ELMWORTH GROVE R 100 EASTMEARN ROAD Waterloo Bridge for Southbank Centre, W x Mondays to Fridays morning peaks only, limited stop 14 IMAX Cinema and London Eye 48 KINGSMEAD ROAD 1 HARPENDEN ROAD 61 31 O 68 Clapham Common Victoria 13 93 w Mondays to Fridays evening peaks only Waterloo O E 51 59 U L West Norwood U 40 V 1 D E N R 43 4 S 445 Fire Station E Vauxhall Bridge Road T 1 St GeorgeÕs Circus O V D O V E A N A G R 14 E R A R O T H for Pimlico 12 1 TOWTON ROAD O R 196 R O N 1 L M W Clapham North O O S T E Red discs show the bus stop you need for your chosen bus A R M I D E I D for Clapham High Street D A T 37 service. -

Vital Christianity

VITAL CHRISTIANITY THE LIFE AND SPIRITUALITY OF WILLIAM WILBERFORCE MURRAY ANDREW PURA CLEMENTS PUBLISHING Toronto CFP Additonal Pages.p651 12/09/2003, 12:45 ISBN 1 85792 916 0 Copyright © 2003 by Murray Andrew Pura Published in 2003 by Christian Focus Publications Ltd., Geanies House, Fearn By Tain, Ross-Shire, Scotland, UK, IV20 1TW www.christianfocus.com and Clements Publishing Box 213, 6021 Yonge Street Toronto, Ontario M2M 3W2 Canada www.clementspublishing.com . Cover Design by Alister MacInnes Printed and Bound by Cox & Wyman, Reading, Berkshire All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical,photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written per- mission of the author, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articlesand reviews. CFP Additonal Pages.p652 12/09/2003, 12:45 v00_1894667107_vital_int.qxd 9/11/03 7:44 AM Page 7 For Donald Munro Lewis teacher, scholar, friend non verba sed tonitrua v00_1894667107_vital_int.qxd 9/11/03 7:44 AM Page 8 v00_1894667107_vital_int.qxd 9/11/03 7:44 AM Page 9 Foreword Little William Wilberforce, like little John Wesley, his older contemporary, was a great man who impacted the Western world as few others have done. Blessed with brains, charm, influence and initiative, much wealth and fair health (though slightly crippled and with chronic digestive difficulties), he put evangelicalism on Britain’s map as a power for social change, first by overthrowing the slave trade almost single-handed and then by generating a stream of societies for doing good and reducing evil in national life. -

THE CLAPHAM SECT LESSON Kanayo N

WEALTH AND POLITICAL INFLUENCE IN THE EXPANSION OF CHRISTIAN FRONTIERS IN CONTEMPORARY NIGERIA: THE CLAPHAM SECT LESSON Kanayo Nwadialor & Chinedu Emmanuel Nnatuanya http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/og.v12i s1.9 Abstract The business of the expansion of any religious frontier is highly demanding. It is a business that has both spiritual and physical components for its effectiveness in the society. Spiritually, it demands prayers while physically; material possessions like money and political influence become veritable tools in enhancing its effectiveness in the world. Historically, the declaration of the Christian faith as legal religion in the Roman Empire by Constantine in the fourth century played a major role in the expansion and the subsequent consolidation of the Church. Likewise, the Clapham sect of the 18 th and 19 th centuries played a significant role in the expansion of the Church beyond the shores of Europe. Their role shows that money and political influence are good vehicles for expanding the gospel of Christ in every part of the world. This work is aimed at a espousing the role of the Clapham sect in the expansion of Christianity in the 19 th century. The aim is to use it as a guide on the best way for Christians to use their wealth and influence towards the expansion of Christianity in contemporary Nigeria. Hence, the work will apply historical method in its evaluation and interpretation. Introduction It is now history that the 18 th century Europe witnesses a rise in the evangelization zeal of Christians in fulfilling the mandate of the great commission, - to take the gospel to the end of the world. -

Buses from Upper Norwood (Beulah Hill) X68 Russell Square Tottenham for British Museum Court Road N68 Holborn Route Finder Aldwych for Covent Garden Day Buses

Buses from Upper Norwood (Beulah Hill) X68 Russell Square Tottenham for British Museum Court Road N68 Holborn Route finder Aldwych for Covent Garden Day buses Bus route Towards Bus stops River Thames Elephant & Castle Ǩ ǫ ǭ Ǯ Waterloo Westwood Hill Lower Sydenham 196 VAUXHALL for IMAX Theatre, London Eye & South Bank Arts Centre Sydenham Bell Green 450 Norwood Junction ɧ ɨ ɩ ɰ Sydenham Lower Sydenham Vauxhall 196 468 Sainsburys Elephant & Castle Fountain Drive Kennington 249 Anerley ɧ ɨ ɩ ɰ Lansdowne Way Lane Route X68 runs non-stop between West Norwood and Walworth Road Waterloo during the Monday-Friday morning peak only. Kingswood Drive SYDENHAM Clapham Common Ǩ ǫ ǭ Ǯ College Road Stockwell Passengers cannot alight before Waterloo. Ā ā 249 Camberwell Green 450 Lower Sydenham Clapham Common Stockwell Green Kingswood Drive Old Town Bowen Drive West Croydon ˓ ˗ Brixton Effra Denmark Hill Road Kings College Hospital Dulwich Wood Park Kingswood Drive 468 Elephant & Castle Ǩ ǫ ǭ Ǯ Brixton Herne Hill Clapham Common South BRIXTON Lambeth Town Hall Dulwich Wood Park CRYSTAL South Croydon ɧ ɨ ɩ ɰ Norwood Road College Road Deronda Road HERNE PALACE Clapham South Norwood Road Crystal Palace Parade HILL College Road Night buses Thurlow Park Road Anerley Road Thicket Road BALHAM Tulse Hill Crystal Palace Anerley Road Bus route Towards Bus stops TULSE Parade Ridsdale Road Balham Anerley Road Norwood Road Hamlet Road Old Coulsdon ɧ ɨ ɩ ɰ HILL Lancaster Avenue N68 Norwood Road Crystal Palace for National Sports Centre Anerley Tottenham Court Road Ǩ ǫ -

The Royalist Maroons of Jamaica in the British Atlantic World, 1740-1800

Os Quilombolas Monarquistas da Jamaica no Mundo Atlântico Britânico, 1740-1800 Th e Royalist Maroons of Jamaica in the British Atlantic World, 1740-1800 Ruma CHOPRA1 https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4838-4678 1 San Jose State University One Washington Square, San Jose, California, 95192, USA [email protected] Resumo Este artigo investiga como uma comunidade de ex-escravos, os quilombolas de Trelawney Town, do norte da Jamaica, sobreviveu à escravidão e ao exílio, aliando-se aos interesses do Império Britânico. A Jamaica, como outras sociedades escravistas do Novo Mundo, produziu fugitivos, e quando esses escravos fugidos estabeleceram comunidades separadas e autônomas de longa duração foram chamados, em inglês, de Maroons e, em português, de quilombolas. O isolamento protegeu os quilombolas jamaicanos da escravidão, mas também os impediu de participar da prosperidade do Império Britânico em expansão. Em 1740, após anos de guerrilha contra a elite colonial, seis grupos quilombolas da ilha assinaram tratados nos quais aceitavam o regime da plantation, optando por usar sua experiência de guerrilha em benefício dos grandes proprietários, e não contra eles. Em troca de sua própria autonomia, tor- naram-se caçadores de escravos e impediram outros escravos de estabe- lecer novas comunidades quilombolas. Porém, décadas de lealdade não evitaram que o maior grupo de quilombolas, o de Trelawney Town, fosse banido. Em 1796, após uma guerra violenta, o governo colonial depor- tou-os sumariamente para a Nova Escócia britânica. Depois de quatro Recebido: 25 abr. 2018 | Revisto: 31 jul. 2018 | Aceito: 15 ago. de 2018 http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/0104-87752019000100008 Varia Historia, Belo Horizonte, vol. -

Brixton and Clapham Park PCN Patient Group Meeting

Brixton and Clapham Park PCN Patient group meeting Notes of meeting held on Zoom 14 April 2021. Present: Nicola Kingston (Chair), Dr Jennie Parker (Chair of PCN, Hetherington), Dave Ball, Ros Borley, Pippa Cardale, Jenny Cobley, Mr & Mrs Day, Craig Givens, Lucy Ismail, Christine Jacobs, Ernestine Montgomerie, Chris Newman (Managing Partner, Clapham Park), Rebecca McNair, Liz Dunbar, Rev Funke Ogbede, Esigbemi Osoba, Martin Pratt, David Ritchie, Maureen Simpson, Sara Taffinder, Peter Woodward. Apologies: Dr Andrew Boyd (Clapham Park), Barbara Wilson, Paulina Tamborrel Signoret (Citizens UK Lambeth). 1. Welcome and introductions. Nicola welcomed everyone and introductions were made. Jenny Cobley agreed to take the notes. 2. Update on the Covid Vaccination programme and surge testing for Covid variants. Dr Jennie Parker reported on the vaccination programme, which is going smoothly at Hetherington Group Practice (HGP), where they now have cover over the waiting area outside. The final delivery of Pfizer vaccine for second doses was due this weekend . The Oxford Astra Zeneca (OAZ) vaccine would also be available for second doses next week, and for those in groups 1-9 who have not yet had the vaccine and for those 45+ years. Chris Newman is organising the vaccination team, they are training more staff, St John’s ambulance personnel and medical students as vaccinators, as the vaccination programme is likely to continue for some months. There is always a lead GP on duty. An increase in uptake among ethnic minority groups has been seen in our area. Uptake of vaccines is 77% overall, with 89% among white, 81% Asian and 65% black patients. -

The Abolition of the British Slave Trade Sofía Muñoz Valdivieso (Málaga, Spain)

The Abolition of the British Slave Trade Sofía Muñoz Valdivieso (Málaga, Spain) 2007 marks the bicentenary of the Abolition of individual protagonists of the abolitionist cause, the Slave Trade in the British Empire. On 25 the most visible in the 2007 commemorations March 1807 Parliament passed an Act that put will probably be the Yorkshire MP William an end to the legal transportation of Africans Wilberforce, whose heroic fight for abolition in across the Atlantic, and although the institution Parliament is depicted in the film production of of slavery was not abolished until 1834, the 1807 Amazing Grace, appropriately released in Act itself was indeed a historic landmark. Britain on Friday, 23 March, the weekend of Conferences, exhibitions and educational the bicentenary. The film reflects the traditional projects are taking place in 2007 to view that places Wilberforce at the centre of commemorate the anniversary, and many the antislavery process as the man who came different British institutions are getting involved to personify the abolition campaign (Walvin in an array of events that bring to public view 157), to the detriment of other less visible but two hundred years later not only the equally crucial figures in the abolitionist parliamentary process whereby the trading in movement, such as Thomas Clarkson, Granville human flesh was made illegal (and the Sharp and many others, including the black antislavery campaign that made it possible), but voices who in their first-person accounts also what the Victoria and Albert Museum revealed to British readers the cruelty of the exhibition calls the Uncomfortable Truths of slave system. -

William Wilberforce

William Wilberforce We may think that Black History Month has little to do with Hull, but it's easy for us to forget that in the 18th Century there was a white man from this city who has come to hold an important place in black history. William Wilberforce was the son of a wealthy Hull merchant. He was born in 1759 in the house that is now the Museum that bears his name in High Street. His grandfather had made the family fortune in the maritime trade with the Baltic countries. William was a small, sickly and delicate child, with poor eyesight. He attended Hull Grammar School but, when he was 9 years old, his father died and, with his mother struggling to cope, William was sent to stay with his uncle and aunt in Wimbledon. Influenced by them, he becam interested in evangelical Christianity. This did not please his mother and grandfather who brought him back to Hull when he was 12 years old and sent him to complete his schooling at Pocklington. At the age of 17, William went to Cambridge University. Shortly afterwards, the deaths of his grandfather and uncle left him independently wealthy and, as a result, he had little inclination or need to apply himself to serious study. Instead, he immersed himself in the social side of student life, with plenty of drinking and gambling. Witty, generous, and an excellent conversationalist, he was a popular figure. He made many friends, including the future Prime Minister William Pitt. Despite his lifestyle and lack of studying he managed to pass his examinations! William began to consider a political career while still at university and was encouraged by William Pitt to join him in obtaining a parliamentary seat.