Lone Survivor” Mission 13 Mar 2018

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

"Batman Returns", Unproduced Draft, by Sam Hamm

"Batman Returns", unproduced draft, by Sam Hamm BATMAN 2 Screenplay By Sam Hamm FIRST DRAFT NOTE: THE HARD COPY OF THIS SCRIPT CONTAINED SCENE NUMBERS. THEY HAVE BEEN REMOVED FOR THIS SOFT COPY. NOTE ALSO: THE HARD COPY OF THIS SCRIPT WAS IN THE NON- PREFORMAT FONT "BOOKMAN OLD". THIS HAS BEEN CHANGED TO PREFORMATTED TEXT FOR THIS SOFT COPY. EXT. GOTHAM SQUARE - DUSK It's finally happened. Hell's frozen over. Christmas is two weeks off, arid SNOW is falling in Gotham. Beneath its pristine white blanket, the city looks uncharacteristically serene -- almost inviting. Peace has been miraculously restored: strangers wave hello. Salvation Army Santas ring their bells on streetcorners. And now, as night falls, an ILLUMINATED SIGN winks on above Broad Avenue: "JOYEUX NOEL GOTHAM -- Only 16 Shopping Days Left Till Christmas." The streets are bustling with jolly shoppers. At a souvenir store, we find an exasperated MOM squabbling with her seven- year old. Like many other storefronts in Gotham, this one is overflowing with bootleg BATMAN MERCHANDISE: t-shirts, key chains, ceramic figurines. The kid is already wearing a Batman baseball cap and a little black cape, but he obviously wants more. Mom drags him off past another store window, this one full of SCRAP METAL, with a sign reading "AUTHENTIC FRAGMENTS OF THE BATWING -- $19.95 and up." A PANHANDLER is perched at the entrance. Beneath his array jacket is a grubby sweatshirt with the familiar yellow-and-black logo. In Gotham this winter, Batmania is everywhere... EXT. GOTHAM SQUARE - LATER THAT NIGHT Two hours later, the SNOWSTORM's grown into a full-fledged blizzard. -

Sundance Institute Presents Institute Sundance U.S

1 Check website or mobile app for full description and content information. description app for full Check website or mobile #sundance • sundance.org/festival sundance.org/festival Sundance Institute Presents Institute Sundance The U.S. Dramatic Competition Films As You Are The Birth of a Nation U.S. Dramatic Competition Dramatic U.S. Many of these films have not yet been rated by the Motion Picture Association of America. Read the full descriptions online and choose responsibly. Films are generally followed by a Q&A with the director and selected members of the cast and crew. All films are shown in 35mm, DCP, or HDCAM. Special thanks to Dolby Laboratories, Inc., for its support of our U.S.A., 2016, 110 min., color U.S.A., 2016, 117 min., color digital cinema projection. As You Are is a telling and retelling of a Set against the antebellum South, this story relationship between three teenagers as it follows Nat Turner, a literate slave and traces the course of their friendship through preacher whose financially strained owner, PROGRAMMERS a construction of disparate memories Samuel Turner, accepts an offer to use prompted by a police investigation. Nat’s preaching to subdue unruly slaves. Director, Associate Programmers Sundance Film Festival Lauren Cioffi, Adam Montgomery, After witnessing countless atrocities against 2 John Cooper Harry Vaughn fellow slaves, Nat devises a plan to lead his DIRECTOR: Miles Joris-Peyrafitte people to freedom. Director of Programming Shorts Programmers SCREENWRITERS: Miles Joris-Peyrafitte, Trevor Groth Dilcia Barrera, Emily Doe, Madison Harrison Ernesto Foronda, Jon Korn, PRINCIPAL CAST: Owen Campbell, DIRECTOR/SCREENWRITER: Nate Parker Senior Programmers Katie Metcalfe, Lisa Ogdie, Charlie Heaton, Amandla Stenberg, PRINCIPAL CAST: Nate Parker, David Courier, Shari Frilot, Adam Piron, Mike Plante, Kim Yutani, John Scurti, Scott Cohen, Armie Hammer, Aja Naomi King, Caroline Libresco, John Nein, Landon Zakheim Mary Stuart Masterson Jackie Earle Haley, Gabrielle Union, Mike Plante, Charlie Reff, Kim Yutani Mark Boone Jr. -

Next Update – April 5, 2016)

COMMUNITY CALENDAR (Next Update – April 5, 2016) Saturday, March 26, 2016, 8:00AM to Noon University of Houston’s Frontier Fiesta March for Marrow 5K Run & Walk at 126 Fred J. Heyne Building, Ste. 104, University of Houston, Houston, TX 77204. Help U of H raise funds to aid the Aplastic Anemia & MDS International Foundation, Inc.’s mission to educate the public about these rare diseases, and to recruit 20 marrow donor candidates for the National Marrow Donor Program. Participants run a 5K on a beautifully designed course that is flat, fast and ideal to beat one’s personal best. Plus, a 1-mile walk for patients and family members going through bone marrow failure diseases and our Brave Little Soles, a Bunny Hop Sack Race for children ages 6 and younger. Log on to www.AAMDS.org/walk or https://friendraising.donorpro.com/campaigns/303 for more information. Friday - Sunday, April 1, 2 & 3, 2016 University of Houston School of Theatre & Dance presents Ensemble Dance Works at the Wortham Theatre, 3351 Cullen Blvd., Houston, TX 77204. Don’t miss this evening of vibrant contemporary works, focusing on themes of humor, mystery, relationship, and movement exploration performed by the pre-professional company, the UH Dance Ensemble, and featuring premiere works by contemporary choreographers John Beasant III, Teresa Chapman, Jaqueline Nalett, Karen Stokes, Toni Valle, Rebecca Valls, and Jane Weiner. Call 713-403-2838 or log on to www.uhtdance.info/ for details. Thursday, April 7, 2016, 11:30AM – 1:00PM Houston Technology Center presents Cyber Attacks: Is Your Business at Risk? at The Woodlands Resort & Conference Center, 2301 North Millbend Drive, The Woodlands, TX 77380. -

Twisted Trails of the Wold West by Matthew Baugh © 2006

Twisted Trails of the Wold West By Matthew Baugh © 2006 The Old West was an interesting place, and even more so in the Wold- Newton Universe. Until fairly recently only a few of the heroes and villains who inhabited the early western United States had been confirmed through crossover stories as existing in the WNU. Several comic book miniseries have done a lot to change this, and though there are some problems fitting each into the tapestry of the WNU, it has been worth the effort. Marvel Comics’ miniseries, Rawhide Kid: Slap Leather was a humorous storyline, parodying the Kid’s established image and lampooning westerns in general. It is best known for ‘outing’ the Kid as a homosexual. While that assertion remains an open issue with fans, it isn’t what causes the problems with incorporating the story into the WNU. What is of more concern are the blatant anachronisms and impossibilities the story offers. We can accept it, but only with the caveat that some of the details have been distorted for comic effect. When the Rawhide Kid is established as a character in the Wold-Newton Universe he provides links to a number of other western characters, both from the Marvel Universe and from classic western novels and movies. It draws in the Marvel Comics series’ Blaze of Glory, Apache Skies, and Sunset Riders as wall as DC Comics’ The Kents. As with most Marvel and DC characters there is the problem with bringing in the mammoth superhero continuities of the Marvel and DC universes, though this is not insurmountable. -

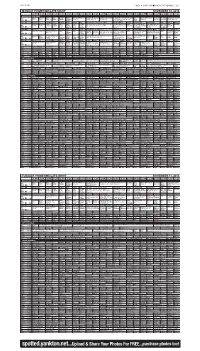

Spotted.Yankton.Net...Upload & Share Your Photos For

PAGE 10B PRESS & DAKOTAN n FRIDAY, NOVEMBER 7, 2014 MONDAY PRIMETIME/LATE NIGHT NOVEMBER 10, 2014 3:00 3:30 4:00 4:30 5:00 5:30 6:00 6:30 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 12:00 12:30 1:00 1:30 BROADCAST STATIONS Arthur Å Arthur Å Wild Wild Martha Nightly PBS NewsHour (N) (In Antiques Roadshow Antiques Roadshow Ice Warriors -- USA Sled Hockey BBC Charlie Rose (N) (In Tavis Smi- The Mind Antiques Roadshow PBS (DVS) (DVS) Kratts Å Kratts Å Speaks Business Stereo) Å “Miami Beach” Å “Madison” Å The U.S. sled hockey team. (In World Stereo) Å ley (N) Å of a Chef “Miami Beach” Å KUSD ^ 8 ^ Report Stereo) Å (DVS) News Å KTIV $ 4 $ Queen Latifah Ellen DeGeneres News 4 News News 4 Ent The Voice The artists perform. (N) Å The Blacklist (N) News 4 Tonight Show Seth Meyers Daly News 4 Extra (N) Hot Bench Hot Bench Judge Judge KDLT NBC KDLT The Big The Voice “The Live Playoffs, Night 1” The art- The Blacklist Red and KDLT The Tonight Show Late Night With Seth Last Call KDLT (Off Air) NBC (N) Å (N) Å Judy (N) Judy (N) News Nightly News Bang ists perform. (N) (In Stereo Live) Å Berlin head to Moscow. News Å Starring Jimmy Fallon Meyers (N) (In Ste- With Car- News Å KDLT % 5 % Å Å (N) Å News (N) (N) Å Theory (N) Å (In Stereo) Å reo) Å son Daly KCAU ) 6 ) Dr. -

The Patriot Tour Featuring Marcus Lutrell, Taya Kyle, Chad Fleming & David Goggins Comes to the Kimmel Center’S Merriam Theater October 20, 2017

Tweet it! Patriot Tour brings @marcusluttrell, @tayakyle, Chad Fleming & @davidgoggins to the @KimmelCenter to discuss military hardships, 10/20. Press Contact: Monica Robinson 215-790-5847 [email protected] THE PATRIOT TOUR FEATURING MARCUS LUTRELL, TAYA KYLE, CHAD FLEMING & DAVID GOGGINS COMES TO THE KIMMEL CENTER’S MERRIAM THEATER OCTOBER 20, 2017 Four well-known patriots visit the Kimmel Center to talk about service, sacrifice, family, community, and their incredible life stories FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE (Philadelphia, PA, August 31, 2017) –– The Kimmel Center, in partnership with Team Never Quits and Mills Entertainment, presents The Patriot Tour featuring retired Navy SEAL Marcus Luttrell, Taya Kyle, retired U.S. Army Capt. Chad Fleming and retired Navy SEAL David Goggins at the Merriam Theater on Friday, October 20, 2017 at 7:30 p.m. This emotional live stage experience highlights incredible stories of perseverance from four remarkable patriots who have had their lives profoundly changed by their service and sacrifice. Tickets are currently on sale and can be purchased at kimmelcenter.org, by phone at 215-893-1999 or at the Kimmel Center Box Office. “The Kimmel Center is incredibly honored to host these four men and women who are brave enough to share the hardships and tragedies they have encountered in their lifetime,” said Anne Ewers, President and CEO of the Kimmel Center for the Performing Arts. “Their stories, marked by service and perseverance, create an emotional experience.” Below is more information about the individual speakers: Featured speaker Marcus Luttrell is the recipient of the Navy Cross for combat heroism and founder of the Lone Survivor Foundation. -

Analisa Pencapaian Objektif Politik AS Dalam Perang Di Afganistan Pada Tahun 2001-2009

Universitas Katolik Parahyangan Fakultas Ilmu Sosial dan Ilmu Politik Program Studi Ilmu Hubungan Internasional Terakreditasi A SK BAN –PT NO: 451/SK/BAN-PT/Akred/S/XI/2014 Analisa Pencapaian Objektif Politik AS Dalam Perang di Afganistan Pada Tahun 2001-2009 Skripsi Oleh Indri Pertami Mullia 2015330009 Bandung 2019 Universitas Katolik Parahyangan Fakultas Ilmu Sosial dan Ilmu Politik Program Studi Ilmu Hubungan Internasional Terakreditasi A SK BAN –PT NO: 451/SK/BAN-PT/Akred/S/XI/2014 Analisa Pencapaian Objektif Politik AS Dalam Perang di Afganistan Pada Tahun 2001-2009 Skripsi Oleh Indri Pertami Mullia 2015330009 Pembimbing Idil Syawfi S.Ip., M.Si. Bandung 2019 Tanda Pengesahan Skripsi Nama : Indri Pertami Mullia Nomor Pokok : 2015330009 Judul : Analisa Pencapaian Objektif Politik AS Dalam Perang di Afganistan Pada Tahun 2001-2009 Telah diuji dalam Ujian Sidang jenjang Sarjana Pada Senin, 22 Juli 2019 Dan dinyatakan LULUS Tim Penguji Ketua sidang merangkap anggota Adrianus Harsawaskita, S.IP., M.A. : ________________________ Sekretaris Idil Syawfi, S.IP., M.Si. : ________________________ Anggota Dr. I Nyoman Sudira : ________________________ Mengesahkan, Dekan Fakultas Ilmu Sosial dan Ilmu Politik Dr. Pius Sugeng Prasetyo, M.Si SURAT PERNYATAAN Saya yang bertandatangan di bawah ini : Nama : Indri Pertami Mullia NPM : 2015330009 Jurusan/Program Studi : Ilmu Hubungan Internasional Judul : Analisa Pencapaian Objektif Politik AS Dalam Perang di Afganistan Pada Tahun 2001-2009 Dengan ini menyatakan bahwa segala konten dalam skripsi ini merupakan hasil karya tulis ilmiah sendiri dan bukan merupakan karya yang pernah diajukan untuk memperoleh gelar akademik oleh pihak lain. Adapun karya atau pendapat pihak lain yang dikutip, telah ditulis sesuai dengan kaidah penulisan ilmiah yang berlaku. -

Inconvenient Truths

Inconvenient Truths Moral Challenges to Combat Leadership Dr. George R. Lucas, Jr. Stockdale Center for Ethical Leadership U.S. Naval Academy (Annapolis) 2 20th Annual Joseph Reich, Sr. Memorial Lecture U.S. Air Force Academy (Colorado Springs) November 7, 2007 “Inconvenient Truths” -Moral Challenges to Combat Leadership in the New Millennium- G. R. Lucas U.S. Naval Academy (Annapolis) General Born, General & Mrs. Wakin, Mr. Joseph Reich, Jr and members of the Reich family, honored guests, and most of all, to the members of the Cadet Wing of the USAFA in attendance here tonight: good evening, and thank you for inviting me to be with you. I represent an organization at the Naval Academy, the Stockdale Center for Ethical Leadership. Don’t be put off that our Center is named after “some Navy guy.” In fact, Vice Admiral Stockdale was – as many of you will also one day be – an accomplished aviator and combat leader. He was, as you no doubt also know, a decorated war hero, including the award of the Congressional Medal of Honor. In his many writings, and in a book with an intriguing title, Philosophical Reflections of a Fighter Pilot, Admiral Stockdale taught, in essence, that the true combat 3 leader and warrior is a teacher, a steward, a jurist, a moralist, and. a philosopher. A “Combat Leader” is . • A Teacher • A Steward •A Jurist • A Moralist • A Philosopher We might pause to reflect upon what Stockdale meant by each of these terms. But regardless of the meaning associated with each, I suspect that this unusual list of traits appears nowhere else in the leadership material you have both studied and learned by example during your time at the Air Force Academy. -

Självständigt Arbete (15 Hp)

Namn Engström, Joel 2021-05-14 Kurs Självständigt arbete (15 hp) Författare Program/Kurs Engström, Joel OP SA 18-21 Handledare Antal ord: 11986 Mariam Bjarnesen Beteckning Kurskod 1OP415 A LONE SEAL – WHAT FAILURE CAN TELL US. ABSTRACT: Special operations are conducted more than ever in modern warfare. Since the 1980s they have developed and grown in numbers. But with more attempts of operations and bigger numbers, comes failures. One of these failures is operation Red Wings where a unit of US Navy SEALs at- tempted a recognisance and raid operation in the Hindu Kush. The purpose of this paper was to see how that failure could be analysed from an existing theory of Special operations. This was to ensure that other failures can be avoided but mainly to understand what really happened on that mountain in 2005. The method used was a case study of a single case to give an answer with quality and depth. The study found that Mcravens theory and principles of how to succeed a special operation was not applied during the operation. The case of operation Red Wings showed remarkable valour and motivation, but also lacked severely when it came to simplicity, surprise, and speed. Nyckelord: T.ex.: Specialoperationer, McRaven, Operation Red Wings, Specialförband. Sida 1 av 41 Namn Engström, Joel 2021-05-14 Kurs Innehållsförteckning 1. INLEDNING ...................................................................................................................................... 3 1.1 PROBLEMFORMULERING .............................................................................................................. -

Among Heroes

Among Heroes A U.S. Navy SEAL’s True Story of Friendship, Heroism, and the Ultimate Sacrifice Brandon Webb with John David Mann Editorial contact: Brent Howard (212) 366-2507 [email protected] Publication date: May 2015 NAL Caliber Published by the Penguin Group Penguin Group (USA) LLC, 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014 USA | Canada | UK | Ireland | Australia | New Zealand | India | South Africa | China penguin.com A Penguin Random House Company First published by NAL Caliber, an imprint of New American Library, a division of Penguin Group (USA) LLC First Printing, June 2015 Copyright Ó 2015 by Brandon Webb Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader. NAL CALIBER and the “C” logo are trademarks of Penguin Group (USA) LLC. LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA: Printed in the United States of America 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Set in Sabon LT Std Designed by Spring Hoteling PUBLISHER’S NOTE Penguin is committed to publishing works of quality and integrity. In that spirit, we are proud to offer this book to our readers; however, the story, the experiences, and the words are the author’s alone. 2 of 169 | Among Heroes, Webb and Mann (12-6-14) To the families 3 of 169 | Among Heroes, Webb and Mann (12-6-14) In thinking back on the days of Easy Company, I’m treasuring my remark to a grandson who asked, “Grandpa, were you a hero in the war?” “No,” I answered, “but I served in a company of heroes.” ― Mike Ranney, quoted in Band of Brothers, by Stephen E. -

Movie Titles List, Genre

ALLEGHENY COLLEGE GAME ROOM MOVIE LIST SORTED BY GENRE As of December 2020 TITLE TYPE GENRE ACTION 300 DVD Action 12 Years a Slave DVD Action 2 Guns DVD Action 21 Jump Street DVD Action 28 Days Later DVD Action 3 Days to Kill DVD Action Abraham Lincoln Vampire Hunter DVD Action Accountant, The DVD Action Act of Valor DVD Action Aliens DVD Action Allegiant (The Divergent Series) DVD Action Allied DVD Action American Made DVD Action Apocalypse Now Redux DVD Action Army Of Darkness DVD Action Avatar DVD Action Avengers, The DVD Action Avengers, End Game DVD Action Aviator DVD Action Back To The Future I DVD Action Bad Boys DVD Action Bad Boys II DVD Action Batman Begins DVD Action Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice DVD Action Black Hawk Down DVD Action Black Panther DVD Action Blood Father DVD Action Body of Lies DVD Action Boondock Saints DVD Action Bourne Identity, The DVD Action Bourne Legacy, The DVD Action Bourne Supremacy, The DVD Action Bourne Ultimatum, The DVD Action Braveheart DVD Action Brooklyn's Finest DVD Action Captain America: Civil War DVD Action Captain America: The First Avenger DVD Action Casino Royale DVD Action Catwoman DVD Action Central Intelligence DVD Action Commuter, The DVD Action Dark Knight Rises, The DVD Action Dark Knight, The DVD Action Day After Tomorrow, The DVD Action Deadpool DVD Action Die Hard DVD Action District 9 DVD Action Divergent DVD Action Doctor Strange (Marvel) DVD Action Dragon Blade DVD Action Elysium DVD Action Ender's Game DVD Action Equalizer DVD Action Equalizer 2, The DVD Action Eragon -

Lone Survivor

UNIVERSAL PICTURES e EMMETT/FURLA FILMS Presentano Una Produzione FILM 44 / EMMETT/FURLA FILMS / HERRICK ENTERTAINMENT / ENVISION ENTERTAINMENT / SPIKINGS ENTERTAINMENT / SINGLE BERRY / CLOSEST TO THE HOLE / LEVERAGE Un Film Scritto e Diretto da PETER BERG MARK WAHLBERG in con TAYLOR KITSCH EMILE HIRSCH BEN FOSTER e ERIC BANA Produttori Esecutivi GEORGE FURLA SIMON FAWCETT BRADEN AFTERGOOD LOUIS G. FRIEDMAN STEPAN MARTIROSYAN REMINGTON CHASE ADI SHANKAR SPENCER SILNA MARK DAMON BRANDT ANDERSEN JEFF RICE Prodotto da PETER BERG SARAH AUBREY RANDALL EMMETT NORTON HERRICK BARRY SPIKINGS AKIVA GOLDSMAN MARK WAHLBERG STEPHEN LEVINSON VITALY GRIGORIANTS Tratto dal Libro di MARCUS LUTTRELL con PATRICK ROBINSON Uscita Italiana: 20 Febbraio 2014 Durata del Film: 121 minuti Il materiale fotografico è disponibile sul sito www.upimedia.com Ufficio Stampa Universal Pictures International Italy: Cristina Casati – [email protected] Marina Caprioli – [email protected] Matilde Marinai – [email protected] Note di Produzione “Non importa quante volte io abbia raccontato questa storia, o quante persone abbiano letto il libro, non è nulla in confronto a quante persone vedranno il film. Ho fatto il mio dovere. Missione compiuta.” —Marcus Luttrell Basato su fatti realmente accaduti descritti nell’omonimo romanzo best seller del New York Times, in tema di eroismo, coraggio e sopravvivenza, Lone Survivor racconta l'incredibile storia di quattro Navy SEAL in missione segreta per neutralizzare un nucleo operativo ad alto rischio di al-Qaeda, finiti in un'imboscata nemica sulle montagne Afghane. Di fronte ad una decisione morale impossibile, il piccolo gruppo rimane isolato dai soccorsi, e circondato da una milizia talebana numericamente più grande e pronta alla guerra.