Body Servants

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

General AP Hill at Gettysburg

Papers of the 2017 Gettysburg National Park Seminar General A.P. Hill at Gettysburg: A Study of Character and Command Matt Atkinson If not A. P. Hill, then who? May 2, 1863, Orange Plank Road, Chancellorsville, Virginia – In the darkness of the Wilderness, victory or defeat hung in the balance. The redoubtable man himself, Stonewall Jackson, had ridden out in front of his most advanced infantry line to reconnoiter the Federal position and was now returning with his staff. Nervous North Carolinians started to fire at the noises of the approaching horses. Voices cry out from the darkness, “Cease firing, you are firing into your own men!” “Who gave that order?” a muffled voice in the distance is heard to say. “It’s a lie! Pour it into them, boys!” Like chain lightning, a sudden volley of musketry flashes through the woods and the aftermath reveals Jackson struck by three bullets.1 Caught in the tempest also is one of Jackson’s division commanders, A. P. Hill. The two men had feuded for months but all that was forgotten as Hill rode to see about his commander’s welfare. “I have been trying to make the men cease firing,” said Hill as he dismounted. “Is the wound painful?” “Very painful, my arm is broken,” replied Jackson. Hill delicately removed Jackson’s gauntlets and then unhooked his sabre and sword belt. Hill then sat down on the ground and cradled Jackson’s head in his lap as he and an aide cut through the commander’s clothing to examine the wounds. -

The Rifle Clubs of Columbia, South Carolina

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Theses and Dissertations 8-9-2014 Before They Were Red Shirts: The Rifle lubC s of Columbia, South Carolina Andrew Abeyounis University of South Carolina - Columbia Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Abeyounis, A.(2014). Before They Were Red Shirts: The Rifle lC ubs of Columbia, South Carolina. (Master's thesis). Retrieved from https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd/2786 This Open Access Thesis is brought to you by Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Before They Were Red Shirts: The Rifle Clubs of Columbia, South Carolina By Andrew Abeyounis Bachelor of Arts College of William and Mary, 2012 ___________________________________________ Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts in Public History College of Arts and Sciences University of South Carolina 2014 Accepted by: Thomas Brown, Director of Thesis Lana Burgess, Reader Lacy Ford, Vice Provost and Dean of Graduate Studies © Copyright by Andrew Abeyounis, 2014 All Rights Reserved. ii DEDICATION This thesis is dedicated to my parents and family who have supported me throughout my time in graduate school. Thank you for reading multiple drafts and encouraging me to complete this project. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS As with every thesis, I would like to thank all the people who helped me finish. I would like to thank my academic advisors including Thomas Brown whose Hist. 800 class provided the foundation for my thesis. -

“Never Have I Seen Such a Charge”

The Army of Northern Virginia in the Gettysburg Campaign “Never Have I Seen Such a Charge” Pender’s Light Division at Gettysburg, July 1 D. Scott Hartwig It was July 1 at Gettysburg and the battle west of town had been raging furiously since 1:30 p.m. By dint of only the hardest fighting troops of Major General Henry Heth’s and Major General Robert E. Rodes’s divisions had driven elements of the Union 1st Corps from their positions along McPherson’s Ridge, back to Seminary Ridge. Here, the bloodied Union regiments and batteries hastily organized a defense to meet the storm they all knew would soon break upon them. This was the last possible line of defense beyond the town and the high ground south of it. It had to be held as long as possible. To break this last line of Union resistance, Confederate Third Corps commander, Lieutenant General Ambrose P. Hill, committed his last reserve, the division of Major General Dorsey Pender. They were the famed Light Division of the Army of Northern Virginia, boasting a battle record from the Seven Days battles to Chancellorsville unsurpassed by any other division in the army. Arguably, it may have been the best division in Lee’s army. Certainly no organization of the army could claim more combat experience. Now, Hill would call upon his old division once more to make a desperate assault to secure victory. In many ways their charge upon Seminary Ridge would be symbolic of why the Army of Northern Virginia had enjoyed an unbroken string of victories through 1862 and 1863, and why they would meet defeat at Gettysburg. -

Wardlaw Family

GENEALOGY OF THE WARDLAW FAMILY WITH SOME ACCOUNT OF OTHER FAMILIES WITH WHICH IT IS CONNECTED DATE MICROFILM GENEALOGICAL DEPARTMENT ITEM ON ROLL CAMERA NO CHURCH OF JESUS CHRIST OF LATTER-DAY SAINTS CATALOGUE NO. iKJJr/? 7-/02 ^s<m BY JOSEPH G. WARDLAW EXPLANATION OF CHARACTERS The letters A, B, C, D, E, F, G, H denote the generations beginning with Robert (Al). The large figures indicate the heads of families, or those especially mentioned in their generation. Each generation begins with 1 and continues in regular sequence. The small figures show number, according to birth, in each particular family. Children dying in infancy or early youth are not mentioned again in line with their brothers and sisters. As the work progressed, new material was received, which, in some measure, interfered with the plan above outlined. Many families named in the early generations have been lost in subsequent tracing, no information being available. By a little examination or study of the system, it will be found possible to trace the lineage of any person named in the book, through all generations back to Robert (Al). PREFACE For a number of years I mave been collecting data con cerning the Wardlaw and allied families. The work was un dertaken for my own satisfaction and pleasure, without thought of publication, but others learning of the material in my hands have urged that it be put into book form. I have had access to MSS. of my father and his brothers, Lewis, Frank and Robert, all practically one account, and presumably obtained from their father, James Wardlaw, who in turn doubtless received it from his father, Hugh. -

Colonel Thomas T. Munford and the Last Cavalry Operations

COLONEL THOMAS T. MUNFORD AND THE LAST CAVALRY OPERATIONS OF THE CIVIL WAR IN VIRGINIA by Anne Trice Thompson Akers Thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in History APPROVED: l%mes I. Robertson, Jr., Chiirmin Thomas Al"/o Adriance Lar;b R. Morrison December, 1981 Blacksburg, Virginia ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I acknowledge, with great respect and admiration, Dr. James I. Robertson, Jr., Chairman of my thesis committee, mentor and friend. He rekindled my ardor for history. With unstinting encouragement, guidance, support and enthusiasm, he kept me in perspective and on course. I also thank Drs. Thomas Adriance and Larry Morrison who served on my committee for their unselfish expense of time and energy and their invaluable criticisms of my work. Special thanks to , Assistant Park Historian, Petersburg National Battlefield, for the map of the Battle of Five Forks, and to , Photographer with the Ohio Agricultural Research and Development Center, who reproduced the map and the photograph. To ., Indian fighter par excellence, I extend warmest regard and appreciation. Simply, I could not have done it without him. I further acknowledge with love my husband who thought I would never do it and my mother who never doubted that I would. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDG}fENTS. • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • . • . • • • • • . • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • . • • • • • • ii Chapter I. MtJNFORD: THE YOUNG MA.N'. • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 2 II. MUNFORD: THE SOLDIER. • • . • . • . • . • • • . • . • • 13 III. FIVE FORKS: WATERLOO OF THE CONFEDERACY .....•...•..•....•• 31 IV. LAST DAYS OF FITZ LEE'S CAVALRY DIVISION .....••..•.••.••... 82 V. MUNFORD: THE RETIRED CAVALRYMAN •.....•......•.......••..•. -

CIVIL WAR HERITAGE TRAILS℠ Alabama April 2017 NEWSLETTER Issue No.57 Southgeorgia Carolina

CIVIL WAR HERITAGE TRAILS℠ Alabama April 2017 NEWSLETTER Issue No.57 www.CivilWarHeritageTrails.org SouthGeorgia Carolina Samuel McGowan Along the Trails April Events Forever Faithful… Samuel McGowan Samuel McGowan was born on October 9, 1819 in Laurens, South Carolina to Irish- immigrant Presbyterian parents. After graduating from South Carolina College (University of South Carolina) in 1841 he studied law at Abbeville, South Carolina and was licensed to practice law in 1842. Continued on Page 2 Along the Trails… Samuel McGowan: Forever Faithful to South Carolina Now nearly 700 Civil War Heritage “trailblazer” signs are installed throughout Georgia along the historic driving routes of the Atlanta Campaign, March to the Sea and Jefferson Davis Heritage Trails. Continued on Page 3 Civil Events in “Along the Trails…” April Events Alabama, Georgia, South Carolina AL – Park Day Atlanta Campaign GA – Leading From the Front and March to the SC – Firing on Fort Sumter: Sea Brochures “The Opening Ball” Continued on Page 4 Follow the Civil War Heritage Trails * www.CivilWarHeritageTrails.org * Facebook * Twitter * YouTube * Pinterest CIVILCIVIL WARWAR HERITAGEHERITAGE TRAILSTRAILS PAGE PAGE 2 2 Samuel McGowan Forever Faithful to South Carolina Copyrighted, All Rights Reserved Samuel McGowan was born on October 9, 1819 in Laurens, South Carolina to Irish-immigrant Presbyterian parents. After graduating from South Carolina College (University of South Carolina) in 1841 he studied law at Abbeville, South Carolina and was licensed to practice law in 1842. Between 1842 and 1861 McGowan spent 13 years in the South Carolina General Assembly. He also served in the U.S. Army during the War with Mexico. -

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in National Register Bulletin, How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. 1. Name of Property Historic name: _Appomattox Court House ______________ _____ Other names/site number: _ Appomattox Court House National Historical Park __________ Name of related multiple property listing : __N/A_________________________________________________________ (Enter "N/A" if property is not part of a multiple property listing ____________________________________________________________________________ 2. Location Street & number: _ Appomattox Court House National Historical Park ________________ City or town: _Appomattox________ State: _Virginia______ County: _Appomattox_____ Not For Publication: Vicinity: ___________________________________________________ _________________________ 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this X nomination ___ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation -

The Making of South Carolina

STORIES OFTHE STATES A THE MAKING OF SOUTH CAROLINA BY HENRY ALEXANDER WHITE, M.A., Ph.D., D.D PROFESSOR IN COLUMBIA. THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY, COLUMBIA, SOUTH CAROLINA; AUTHOR OF "LIFE OF- ROBERT E. LEE," AND "A SCHOOL HISTORY OF THE UNITED STATES." WITH MANY ILLUSTRATIONS AND MAPS SILVER, BURDETT AND COMPANY NEW YORK ATLANTA BOSTON DALLAS CHICAGO r\ Checked it inn * From the portrait by Healy JOHN C. CALHOUN PUBLIC LIBRARY 373782 ASTOR, LENOX AND TILDE.N FOUNDATIONS. R 1906 L Copyright, 1900, by SILVER, BURDETT AND COMPANY This Book is Dedicated to Mi] MiU Fanny Beverley Wellford White PREFACE. This book attempts to give a short, simple history of South Carolina from the first settlement to the present day. Biographical sketches of rulers and leaders are arranged in close connection in order to furnish a con- tinuous historical narrative. The story of the lives of many great and good men of the state is of necessity left out; the boys and girls of South Carolina must read about them in larger books than this. Many worthy and noble women have also helped to build up and strengthen the state of South Carolina. In Colonial and Revolutionary days, and most of all during the period of the Southern Confederacy, they toiled and suffered in behalf of their people. It is not possible, however, in these brief pages to give the story of their deeds of devotion and self-sacrifice. The statements made in this book are based through- out on public records and on the original writings of those who had a share in the events and deeds herein described. -

Collection 1805.060.021: Photographs of Union and Confederate Officers in the Civil War in America – Collection of Brevet Lieutenant Colonel George Meade U.S.A

Collection 1805.060.021: Photographs of Union and Confederate Officers in the Civil War in America – Collection of Brevet Lieutenant Colonel George Meade U.S.A. Alphabetical Index The Heritage Center of The Union League of Philadelphia 140 South Broad Street Philadelphia, PA 19102 www.ulheritagecenter.org [email protected] (215) 587-6455 Collection 1805.060.021 Photographs of Union and Confederate Officers - Collection of Bvt. Lt. Col. George Meade U.S.A. Alphabetical Index Middle Last Name First Name Name Object ID Description Notes Portrait of Major Henry L. Abbott of the 20th Abbott was killed on May 6, 1864, at the Battle Abbott Henry L. 1805.060.021.22AP Massachusetts Infantry. of the Wilderness in Virginia. Portrait of Colonel Ira C. Abbott of the 1st Abbott Ira C. 1805.060.021.24AD Michigan Volunteers. Portrait of Colonel of the 7th United States Infantry and Brigadier General of Volunteers, Abercrombie John J. 1805.060.021.16BN John J. Abercrombie. Portrait of Brigadier General Geo. (George) Stoneman Chief of Cavalry, Army of the Potomac, and staff, including Assistant Surgeon J. Sol. Smith and Lieutenant and Assistant J. Adjutant General A.J. (Andrew Jonathan) Alexander A. (Andrew) (Jonathan) 1805.060.021.11AG Alexander. Portrait of Brigadier General Geo. (George) Stoneman Chief of Cavalry, Army of the Potomac, and staff, including Assistant Surgeon J. Sol. Smith and Lieutenant and Assistant J. Adjutant General A.J. (Andrew Jonathan) Alexander A. (Andrew) (Jonathan) 1805.060.021.11AG Alexander. Portrait of Captain of the 3rd United States Cavalry, Lieutenant Colonel, Assistant Adjutant General of the Volunteers, and Brevet Brigadier Alexander Andrew J. -

The North Carolina Historical Review

" The North Carolina Historical Review Volume XVIII October, 1941 Number 4 GOVERNOR VANCE AND THE END OF THE WAR IN NORTH CAROLINA By Richard E. Yates When Zebulon B. Vance was reelected to the governorship of North Carolina in August, 1864, he had ample reason to be proud of his achievement. By an overwhelming majority he had defeated William W. Holden, the " peace candidate, and the ominous peace movement which he led. "I have beaten him," Vance said proudly, worse than any man was rn ever beaten in North Carolina. But as the popular young governor surveyed the condition of the Southern cause, he found much to depress him. By little more than a mere skirmish line, Lee was holding Grant's large army before Petersburg ; and the Army of the Tennessee under Hood was being pressed back to Atlanta by the persistent Sherman. Before the well trained, fully equipped armies of the United States, the Confederate forces were quickly wasting away. Death and disease took thousands who could not be re- placed; and thousands more, despairing for the cause and sick of the war, deserted from the armies and nocked to the mountains, where many of them lived a life of robbery and murder. Realizing that the South's only chance for success lay in increasing its armed forces, Governor Vance made energetic efforts to fill the rapidly dwindling North Carolina regiments. On the basis of orders issued by General Lee, he published a proclamation in August, 1864, promising that all deserters who returned voluntarily within thirty days would receive only a nominal punishment. -

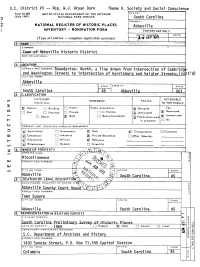

S.C. District #3 Rep. W.J. Bryan Dorn Theme 9

S.C. District #3 Rep. W.J. Bryan Dorn Theme 9. Society and Social Conscience Form 10-300 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR STATE: (July 1969) NATIONAL PARK SERVICE South Carolina COUNTY: NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES Abbeville INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM FOR NPS USE ONLY (Type all entries — complete applicable sections) Abbeville Historic District AND/OR HISTORIC: NUMBER: Boundaries: North, a line drawn from intersection of Cambridge and Washington Streets to intersection of Harrisburg and Haigler Streets;(coit 1 d) CITY OR TOWN: Abbeville South Carolina 45 Abbevilie 3- CLASSIFICATION CATEGORY ACCESSIBLE OWNERSHIP STATUS (Check One) TO THE PUBLIC District Q Building Public Public Acquisition: Occupied Yes: O Restricted Site Q Structure Private || In Process Unoccupied jj^l Unrestricted D Object Both [~~] Being Considered Preservation work in progress a NO PRESENT USE (Check One or More as Appropriate) Agricultural | | Government Transportation I I Comments Commercial | | Industrial Kl Private Residence Other (Specify) Educational [^] Military QQ Religious Entertainment Q Museum I I Scientific K'OWNER'OF PROPERTY COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS, E Abbe vi lie County Court STREET AND NUMBER: Town Square Cl TY OR TOWN: Abbeville South Carolina 45 IN EXISTtNG SURVEYS TITLE OF SURVEY: South Carolina Preliminary Survey of Historic Places DATE OF SURVEY: 1969 Federol State I | County | | Local DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS: S.C. Department of Archives and History STREET AND NUMBER: 1430 Senate Street, P.O. Box 11,188 Capitol Station CITY OR TOWN: STATE: Columbia South Carolina 45 (Check One) [XJ Excellent G °°d Fai ] Deteriorated Q Ruins Unexposed CONDITION (Check One) (Check One) Altered [X Unaltered Moved (XJ Origin^, Slfe, ; ' f? DESCRIBE TJ4P.• PRESENT' AND ORIGINAL (if known) PHYSICAL. -

Wade Hampton and the Rhetoric of Race: a Study of the Speaking of Wade Hampton on the Race Issue in South Carolina, 1865-1878

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1988 Wade Hampton and the Rhetoric of Race: A Study of the Speaking of Wade Hampton on the Race Issue in South Carolina, 1865-1878. Dewitt Grant Jones Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Jones, Dewitt Grant, "Wade Hampton and the Rhetoric of Race: A Study of the Speaking of Wade Hampton on the Race Issue in South Carolina, 1865-1878." (1988). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 4510. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/4510 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS The most advanced technology has been used to photo graph and reproduce this manuscript from the microfilm master. UMI films the original text directly from the copy submitted. Thus, some dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from a computer printer. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyrighted material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are re produced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps.