National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Appomattox Court House

GPO 1979 281-357/43 Repiint 1979 Here on April 9, 1865, Gen. Robert E. Lee surren cause. Nor could Lee, in conscience, disband his FOR YOUR SAFETY Appomattox dered the Confederacy's largest and most success army to allow the survivors to carry on guerrilla ful field army to Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant. The warfare. Early on Palm Sunday, April 9, the Con Please do not pet or feed the animals in the park. Court House surrender of the rest of the Confederate com federates ran head-on into the blue-coated infantry Structures, plants, and animals may all pose a mands followed within weeks. and were stopped. Grant had closed the gate. danger to the unwary. Be careful. "There is nothing left for me to do but to go and Lee's ragged and starving army had begun its long see General Grant," Lee concluded, "and I would march to Appomattox on Passion Sunday, April 2, ADMINISTRATION rather die a thousand deaths." when Grant's Federal armies finally cracked the Appomattox Court House National Historical Park Richmond and Petersburg defense lines after 10 The two generals met in the home of Wilmer is administered by the National Park Service, U.S. months of siege. The march had been an exhaust McLean at Appomattox Court House. Lee's face Department of the Interior. A superintendent, ing one, filled with frustration and lost hopes. revealed nothing of his feelings and Grant could whose address is Box 218, Appomattox, VA 24522, Deprived of their supply depots and rapidly losing not decide whether the Confederate commander is in immediate charge. -

Appomattox Court House Is on the Crest of a 770-Foot High Ridge

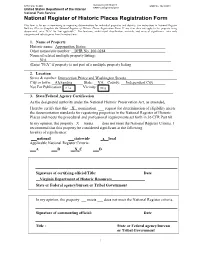

NFS Form 1MOO OWB No. 1024-O01S United States Department of the Interior National Park Service I 9 /98g National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations of eligibility for individual properties or districts. See instructions in Guidelines for Completing National Register Forms (National Register Bulletin 16). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the requested information. If an item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, styles, materials, and areas of significance, enter only the categories and subcategories listed in the instructions. For additional space use continuation sheets (Form 10-900a). Type all entries. 1. Name of Property historic name APPnMATTnY rnriPT unn^F other names/site number APPOM ATTnY ^HITBT HHTTC;P MATTDMAT HISTOPICAT. PARK 2. Location , : _ | not for publication street & nurnberAPPOMATTOX COUPT" HOUSE NATIONAL HISTO RICAL PAR city, town APPOMATTOX v| vicinity code " ~ "* state TrrnrrxTTA code CH county APPnMATTnY Q I T_ zip code 2^579 3. Classification Ownership of Property Category of Property Number of Resources within Property a private n building(s) Contributing Noncontributing public-local B district 31 3 buildings 1 1 public-State site Q sites f_xl public-Federal 1 1 structure lit 1 fl structures CH object 1 objects Name of related multiple property listing: Number of contributing resources previously None_________ listed in the National Register 0_____ 4. State/Federal Agency Certification Asjhe designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this Sd nomination I I request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. -

List of Staff Officers of the Confederate States Army. 1861-1865

QJurttell itttiuetsity Hibrary Stliaca, xV'cni tUu-k THE JAMES VERNER SCAIFE COLLECTION CIVIL WAR LITERATURE THE GIFT OF JAMES VERNER SCAIFE CLASS OF 1889 1919 Cornell University Library E545 .U58 List of staff officers of the Confederat 3 1924 030 921 096 olin The original of this book is in the Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924030921096 LIST OF STAFF OFFICERS OF THE CONFEDERATE STATES ARMY 1861-1865. WASHINGTON: GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE. 1891. LIST OF STAFF OFFICERS OF THE CONFEDERATE ARMY. Abercrombie, R. S., lieut., A. D. C. to Gen. J. H. Olanton, November 16, 1863. Abercrombie, Wiley, lieut., A. D. C. to Brig. Gen. S. G. French, August 11, 1864. Abernathy, John T., special volunteer commissary in department com- manded by Brig. Gen. G. J. Pillow, November 22, 1861. Abrams, W. D., capt., I. F. T. to Lieut. Gen. Lee, June 11, 1864. Adair, Walter T., surg. 2d Cherokee Begt., staff of Col. Wm. P. Adair. Adams, , lieut., to Gen. Gauo, 1862. Adams, B. C, capt., A. G. S., April 27, 1862; maj., 0. S., staff General Bodes, July, 1863 ; ordered to report to Lieut. Col. R. G. Cole, June 15, 1864. Adams, C, lieut., O. O. to Gen. R. V. Richardson, March, 1864. Adams, Carter, maj., C. S., staff Gen. Bryan Grimes, 1865. Adams, Charles W., col., A. I. G. to Maj. Gen. T. C. Hiudman, Octo- ber 6, 1862, to March 4, 1863. Adams, James M., capt., A. -

Appomattox Statue Other Names/Site Number: DHR No

NPS Form 10-900 VLR Listing 03/16/2017 OMB No. 1024-0018 United States Department of the Interior NRHP Listing 06/12/2017 National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in National Register Bulletin, How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. 1. Name of Property Historic name: Appomattox Statue Other names/site number: DHR No. 100-0284 Name of related multiple property listing: N/A (Enter "N/A" if property is not part of a multiple property listing ____________________________________________________________________________ 2. Location Street & number: Intersection Prince and Washington Streets City or town: Alexandria State: VA County: Independent City Not For Publication: N/A Vicinity: N/A ____________________________________________________________________________ 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this X nomination ___ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements -

James Longstreet and the Retreat from Gettysburg

“Such a night is seldom experienced…” James Longstreet and the Retreat from Gettysburg Karlton Smith, Gettysburg NMP After the repulse of Lt. Gen. James Longstreet’s Assault on July 3, 1863, Gen. Robert E. Lee, commanding the Army of Northern Virginia, knew that the only option left for him at Gettysburg was to try to disengage from his lines and return with his army to Virginia. Longstreet, commander of the army’s First Corps and Lee’s chief lieutenant, would play a significant role in this retrograde movement. As a preliminary to the general withdrawal, Longstreet decided to pull his troops back from the forward positions gained during the fighting on July 2. Lt. Col. G. Moxley Sorrel, Longstreet’s adjutant general, delivered the necessary orders to Maj. Gen. Lafayette McLaws, commanding one of Longstreet’s divisions. Sorrel offered to carry the order to Brig. Gen. Evander M. Law, commanding John B. Hood’s division, on McLaws’s right. McLaws raised objections to this order. He felt that his advanced position was important and “had been won after a deadly struggle; that the order was given no doubt because of [George] Pickett’s repulse, but as there was no pursuit there was no necessity of it.” Sorrel interrupted saying: “General, there is no discretion allowed, the order is for you to retire at once.” Gen. James Longstreet, C.S.A. (LOC) As McLaws’s forward line was withdrawing to Warfield and Seminary ridges, the Federal batteries on Little Round Top opened fire, “but by quickening the pace the aim was so disturbed that no damage was done.” McLaws’s line was followed by “clouds of skirmishers” from the Federal Army of the Potomac; however, after reinforcing his own skirmish line they were driven back from the Peach Orchard area. -

“Never Was I So Depressed”

The Army of Northern Virginia in the Gettysburg Campaign “Never Was I So Depressed” James Longstreet and Pickett’s Charge Karlton D. Smith On July 24, 1863, Lt. Gen. James Longstreet wrote a private letter to his uncle, Augusts Baldwin Longstreet. In discussing his role in the Gettysburg Campaign, the general stated: General Lee chose the plan adopted, and he is the person appointed to chose and to order. I consider it a part of my duty to express my views to the commanding general. If he approves and adopts them it is well; if he does not, it is my duty to adopt his views, and to execute his orders as faithfully as if they were my own. While clearly not approving Lee’s plan of attack on July 3, Longstreet did everything he could, both before and during the attack, to ensure its success.1 Born in 1821, James Longstreet was an 1842 graduate of West Point. An “Old Army” regular, Longstreet saw extensive front line combat service in the Mexican War in both the northern and southern theaters of operations. Longstreet led detachments that helped to capture two of the Mexican forts guarding Monterey and was involved in the street fighting in the city. At Churubusco, Longstreet planted the regimental colors on the walls of the fort and saw action at Casa Marta, near Molino del Ray. On August 13, 1847, Longstreet was wounded during the assault on Chapaltepec while “in the act of discharging the piece of a wounded man." The same report noted that during the action, "He was always in front with the colors. -

The Knapsack Raleigh Civil War Round Table the Same Rain Falls on Both Friend and Foe

The Knapsack Raleigh Civil War Round Table The same rain falls on both friend and foe. June 24, 2017 Volume 17 Our 196th Meeting Number 6 http://www.raleighcwrt.org June 24 Meeting Features Symposium On Reconstruction in North Carolina The Raleigh Civil War Round Table’s June 2017 NOTE: The symposium will be held at our usual meeting will be a special weekend event featuring meeting place at the N.C. Museum of History but will four well-known authors and historians speaking on run from 9 a.m. until 4 p.m. on Sat., June 24. The reconstruction in North Carolina. event also will cost $30 per person. Federal Occupation of North Carolina Women’s Role in Reconstruction Mark Bradley, staff historian at the Angela Robbins, assistant professor of U.S. Army Center of Military History in history at Meredith College in Raleigh, Washington, D.C., will speak on the will speak on the women’s role in re- federal occupation. Mark is nationally construction. She has also taught at known for his knowledge of the Battle UNC-Greensboro and Wake Forest of Bentonville and the surrender at University. She received her Ph.D. in Bennett Place. He also is an award- U.S. History from UNC-Greensboro in winning author, having written This 2010. Her dissertation research looked Astounding Close: The Road to Bennett Place, Last at strategies used by women in the North Carolina Stand in the Carolinas: The Battle of Bentonville, Piedmont to support themselves and their families in and Bluecoats and Tar Heels: Soldiers and Civilians the unstable post-Civil War economy. -

Stonewall Jackson

AMERICAN CRISIS BIOGRAPHIES STONEWALL JACKSON HENRY ALEXANDER WHITE. A.M.. Ph.D. Author of " Robert E. Lee and the Southern Confederacy," "A History of the United States," etc. PHILADELPHIA GEORGE W. JACOBS & COMPANY PUBLISHERS COPYRIGHT, 1908, BY GEORGE W. JACOBS & COMPANY Published January, 1909 This volume is dedicated to My Wife Fanny Beverley Wellford White PREFACE THE present biography of Stonewall Jackson is based upon an examination of original sources, as far as these are available. The accounts of Jack son s early life and of the development of his per sonal character are drawn, for the most part, from Doctor Eobert L. Dabney s biography and from Jackson s Life and Letters, by Mrs. Jackson. The Official Eecords of the war, of course, constitute the main source of the account here given of Jackson s military operations. Colonel G. F. E. Henderson s Life is an admirable of his career study military ; Doctor Dabney s biography, however, must remain the chief source of our knowledge concerning the personality of the Confederate leader. Written accounts by eye-witnesses, and oral statements made to the writer by participants in Jackson s campaigns, have been of great service in the preparation of this volume. Some of these are mentioned in the partial list of sources given in the bibliography. HENRY ALEXANDER WHITE. Columbia, S. C. CONTENTS CHRONOLOGY 11 I. EARLY YEARS 15 II. AT WEST POINT .... 25 III. THE MEXICAN WAR ... 34 IV. THE VIRGINIA MILITARY INSTITUTE 47 V. THE BEGINNING OF WAR . 63 VI. COMMANDER OF VOLUNTEERS AT HARPER S FERRY .. -

STONEWALL JACKSON in FAYETTE COUNTY

STONEWALL JACKSON in FAYETTE COUNTY Larry Spurgeon1 (2019) ***** … the history of Jackson’s boyhood has become “an oft told tale,” so much so that one’s natural inclination is to pass over this period in silence. Yet under the circumstances this should not be done, for it is due Jackson’s memory, as well as his admirers, that the facts, as far as known, of that part of his life be at least accurately if but briefly narrated. Thomas Jackson Arnold2 __________ Thomas Jonathan “Stonewall” Jackson is one of the most iconic figures in American history. While most research has understandably focused on the Civil War, his early life in western Virginia, now West Virginia, has been the subject of some fascination. We are drawn to stories about someone who rises from humble circumstances to the pinnacle of success. A consensus narrative about his childhood evolved over time, an “oft told tale,” to be sure, but one that has gaps, errors, and even myths. An excerpt from the historical marker at Westlake Cemetery in Ansted, Fayette County, West Virginia, where Jackson’s mother Julia is buried, is a good example: On November 4, 1830, Julia Jackson married Blake G. Woodson, a man fifteen years her senior, who in 1831 became the court clerk of newly created Fayette County. Mired in poverty despite his position, he resented his stepchildren. When Julia Woodson’s health began to fail in 1831, she sent her children to live with relatives, and Thomas J. Jackson moved to Jackson’s Mill in Lewis County. He returned here once, in autumn 1831, to see his mother shortly before she died. -

General AP Hill at Gettysburg

Papers of the 2017 Gettysburg National Park Seminar General A.P. Hill at Gettysburg: A Study of Character and Command Matt Atkinson If not A. P. Hill, then who? May 2, 1863, Orange Plank Road, Chancellorsville, Virginia – In the darkness of the Wilderness, victory or defeat hung in the balance. The redoubtable man himself, Stonewall Jackson, had ridden out in front of his most advanced infantry line to reconnoiter the Federal position and was now returning with his staff. Nervous North Carolinians started to fire at the noises of the approaching horses. Voices cry out from the darkness, “Cease firing, you are firing into your own men!” “Who gave that order?” a muffled voice in the distance is heard to say. “It’s a lie! Pour it into them, boys!” Like chain lightning, a sudden volley of musketry flashes through the woods and the aftermath reveals Jackson struck by three bullets.1 Caught in the tempest also is one of Jackson’s division commanders, A. P. Hill. The two men had feuded for months but all that was forgotten as Hill rode to see about his commander’s welfare. “I have been trying to make the men cease firing,” said Hill as he dismounted. “Is the wound painful?” “Very painful, my arm is broken,” replied Jackson. Hill delicately removed Jackson’s gauntlets and then unhooked his sabre and sword belt. Hill then sat down on the ground and cradled Jackson’s head in his lap as he and an aide cut through the commander’s clothing to examine the wounds. -

The Rifle Clubs of Columbia, South Carolina

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Theses and Dissertations 8-9-2014 Before They Were Red Shirts: The Rifle lubC s of Columbia, South Carolina Andrew Abeyounis University of South Carolina - Columbia Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Abeyounis, A.(2014). Before They Were Red Shirts: The Rifle lC ubs of Columbia, South Carolina. (Master's thesis). Retrieved from https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd/2786 This Open Access Thesis is brought to you by Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Before They Were Red Shirts: The Rifle Clubs of Columbia, South Carolina By Andrew Abeyounis Bachelor of Arts College of William and Mary, 2012 ___________________________________________ Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts in Public History College of Arts and Sciences University of South Carolina 2014 Accepted by: Thomas Brown, Director of Thesis Lana Burgess, Reader Lacy Ford, Vice Provost and Dean of Graduate Studies © Copyright by Andrew Abeyounis, 2014 All Rights Reserved. ii DEDICATION This thesis is dedicated to my parents and family who have supported me throughout my time in graduate school. Thank you for reading multiple drafts and encouraging me to complete this project. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS As with every thesis, I would like to thank all the people who helped me finish. I would like to thank my academic advisors including Thomas Brown whose Hist. 800 class provided the foundation for my thesis. -

Historic Cabarrus Newsmagazine 5

THE NEWSMAGAZINE OF HISTORIC CABARRUS ASSOCIATION, INC. HISTORIC CABARRUS ASSOCIATION,PAST INC. TIMES P.O. Box 966 Winter 2011 Issue No. 5 historiccabarrus.org Concord, NC 28026 TELEPHONE (704) 782-3688 FIND US ON FACEBOOK! This issue’s Cabarrus County During Wartime: highlights The War Between the States include... SPECIAL EXHIBIT OBSERVES THE 150TH ANNIVERSARY OF THE CIVIL WAR VISIT OUR TWO MUSEUMS IN DOWNTOWN CONCORD: CONCORD MUSEUM Union Street Square Confederate hand grenades among items on display at Concord Museum. 11 Union Street South, Suite 104 Concord, NC 28025 Open Tuesdays through Saturdays, 11 AM until 3 PM CABARRUS COUNTY VETERANS MUSEUM Historic Courthouse New curator gives Concord Museum a 65 Union Street South, First Floor New Concord book, pg. 4. Concord, NC 28025 makeover, pg. 7. Open Mondays through Fridays, 10 AM until 4 PM Free admission. Group tours by appointment. Donations warmly appreciated. Past Times No. 5, Winter 2011 PAST TIMES! PAGE2 Grand opening of the Concord Museum’s “War Between the States” special exhibit, Friday, February Michael Eury, Editor. 11, 2011. Approximately 200 people visited the museum that evening. One hundred and fifty years ago, in early Presented therein is an array of Civil 1861, tensions smoldered between the War-era weapons, uniforms, flags, northern and southern United States over photographs, oil paintings, and other artifacts BOARD OF states’ rights versus federal jurisdiction, revisiting this important era of Southern DIRECTORS westward expansion, and slavery. These history. For a limited time, visitors will be able disagreements gave way to The War to see original Confederate regiment banners R.