Volume 11 Hijmoer 38 Copiapoa Sh

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University of Florida Thesis Or Dissertation Formatting

SYSTEMATICS OF TRIBE TRICHOCEREEAE AND POPULATION GENETICS OF Haageocereus (CACTACEAE) By MÓNICA ARAKAKI MAKISHI A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2008 1 © 2008 Mónica Arakaki Makishi 2 To my parents, Bunzo and Cristina, and to my sisters and brother. 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I want to express my deepest appreciation to my advisors, Douglas Soltis and Pamela Soltis, for their consistent support, encouragement and generosity of time. I would also like to thank Norris Williams and Michael Miyamoto, members of my committee, for their guidance, good disposition and positive feedback. Special thanks go to Carlos Ostolaza and Fátima Cáceres, for sharing their knowledge on Peruvian Cactaceae, and for providing essential plant material, confirmation of identifications, and their detailed observations of cacti in the field. I am indebted to the many individuals that have directly or indirectly supported me during the fieldwork: Carlos Ostolaza, Fátima Cáceres, Asunción Cano, Blanca León, José Roque, María La Torre, Richard Aguilar, Nestor Cieza, Olivier Klopfenstein, Martha Vargas, Natalia Calderón, Freddy Peláez, Yammil Ramírez, Eric Rodríguez, Percy Sandoval, and Kenneth Young (Peru); Stephan Beck, Noemí Quispe, Lorena Rey, Rosa Meneses, Alejandro Apaza, Esther Valenzuela, Mónica Zeballos, Freddy Centeno, Alfredo Fuentes, and Ramiro Lopez (Bolivia); María E. Ramírez, Mélica Muñoz, and Raquel Pinto (Chile). I thank the curators and staff of the herbaria B, F, FLAS, LPB, MO, USM, U, TEX, UNSA and ZSS, who kindly loaned specimens or made information available through electronic means. Thanks to Carlos Ostolaza for providing seeds of Haageocereus tenuis, to Graham Charles for seeds of Blossfeldia sucrensis and Acanthocalycium spiniflorum, to Donald Henne for specimens of Haageocereus lanugispinus; and to Bernard Hauser and Kent Vliet for aid with microscopy. -

South American Cacti in Time and Space: Studies on the Diversification of the Tribe Cereeae, with Particular Focus on Subtribe Trichocereinae (Cactaceae)

Zurich Open Repository and Archive University of Zurich Main Library Strickhofstrasse 39 CH-8057 Zurich www.zora.uzh.ch Year: 2013 South American Cacti in time and space: studies on the diversification of the tribe Cereeae, with particular focus on subtribe Trichocereinae (Cactaceae) Lendel, Anita Posted at the Zurich Open Repository and Archive, University of Zurich ZORA URL: https://doi.org/10.5167/uzh-93287 Dissertation Published Version Originally published at: Lendel, Anita. South American Cacti in time and space: studies on the diversification of the tribe Cereeae, with particular focus on subtribe Trichocereinae (Cactaceae). 2013, University of Zurich, Faculty of Science. South American Cacti in Time and Space: Studies on the Diversification of the Tribe Cereeae, with Particular Focus on Subtribe Trichocereinae (Cactaceae) _________________________________________________________________________________ Dissertation zur Erlangung der naturwissenschaftlichen Doktorwürde (Dr.sc.nat.) vorgelegt der Mathematisch-naturwissenschaftlichen Fakultät der Universität Zürich von Anita Lendel aus Kroatien Promotionskomitee: Prof. Dr. H. Peter Linder (Vorsitz) PD. Dr. Reto Nyffeler Prof. Dr. Elena Conti Zürich, 2013 Table of Contents Acknowledgments 1 Introduction 3 Chapter 1. Phylogenetics and taxonomy of the tribe Cereeae s.l., with particular focus 15 on the subtribe Trichocereinae (Cactaceae – Cactoideae) Chapter 2. Floral evolution in the South American tribe Cereeae s.l. (Cactaceae: 53 Cactoideae): Pollination syndromes in a comparative phylogenetic context Chapter 3. Contemporaneous and recent radiations of the world’s major succulent 86 plant lineages Chapter 4. Tackling the molecular dating paradox: underestimated pitfalls and best 121 strategies when fossils are scarce Outlook and Future Research 207 Curriculum Vitae 209 Summary 211 Zusammenfassung 213 Acknowledgments I really believe that no one can go through the process of doing a PhD and come out without being changed at a very profound level. -

0111 2011.Pdf

SULCOREBUTIA, FOOD FOR TAXONOMISTS ? Johan Pot Many cactus lovers seem to have an opinion about the nomenclature of their plants. But do they really know the right name? Who will determine this and in particular, how is it done ? We haven’t heard the last word on this subject. Creation of the image this from the name. And I heard it perso- My cactus hobby was scarcely born, when nally from Backeberg. He cannot be I met Karel. He presented himself as a wrong, as he found them himself. You say very experienced collector. He invited me Echinopsis? You mean Echinocactus? But emphatically to visit him. And not to hesi- these plants are lobivias and there is an tate in asking any question. As I was eager end to it !” to learn, I accepted the invitation gladly. I didn’t understand much of it. Had Jaap Within a week I had entered his sanctum. really had contact with the famous Backe- It was indeed a paradise. Many plants berg ? On the other hand Gijs didn’t look were in bloom. In every flowerpot there stupid. I chose to keep silent as I didn’t was a label with a name on it. This was want to be thought a dummy. A few mi- quite a different experience to “120 cacti nutes later the guests left. Karel muttered in colour”. to me in offended tones “This Jaap, he Shortly before the visit somebody asked must always know better! The only thing me, if I already had the “hand of the ne- that really matters is that you understand gro” (Maihuenopsis clavarioides). -

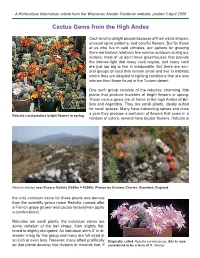

Cactus Gems from the High Andes

A Horticulture Information article from the Wisconsin Master Gardener website, posted 3 April 2009 Cactus Gems from the High Andes Cacti tend to delight people because of their weird shapes, unusual spine patterns, and colorful fl owers. But for those of us who live in cold climates, our options for growing them are limited: relatively few survive outdoors during our winters; most of us don’t have greenhouses that provide the intense light that many cacti require; and many cacti are just too big to live in windowsills. But there are sev- eral groups of cacti that remain small and live in habitats where they are adapted to lighting conditions that are less intense than those found in the Tucson desert. One such group consists of the rebutias, charming little plants that produce bunches of bright fl owers in spring. These cactus gems are at home in the high Andes of Bo- livia and Argentina. They are small plants, ideally suited for small spaces. Many have interesting spines and once a year they produce a profusion of fl owers that come in a Rebutia cacti produce bright fl owers in spring. rainbow of colors; several have bicolor fl owers. Rebutia is Rebutia fi ebrigii near Pucara, Bolivia (2850m = 9350ft). Photos by Graham Charles, Stamford, England. the only common name for these plants and derives from the scientifi c genus name Rebutia, named after a French grape grower and cactus nurseryman (quite a combination!). Rebutias are small plants, the individual stems are some variation of the ball shape, from slightly fl at- tened to slightly elongated. -

Phylogenetic Relationships in the Cactus Family (Cactaceae) Based on Evidence from Trnk/Matk and Trnl-Trnf Sequences

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: http://www.researchgate.net/publication/51215925 Phylogenetic relationships in the cactus family (Cactaceae) based on evidence from trnK/matK and trnL-trnF sequences ARTICLE in AMERICAN JOURNAL OF BOTANY · FEBRUARY 2002 Impact Factor: 2.46 · DOI: 10.3732/ajb.89.2.312 · Source: PubMed CITATIONS DOWNLOADS VIEWS 115 180 188 1 AUTHOR: Reto Nyffeler University of Zurich 31 PUBLICATIONS 712 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE Available from: Reto Nyffeler Retrieved on: 15 September 2015 American Journal of Botany 89(2): 312±326. 2002. PHYLOGENETIC RELATIONSHIPS IN THE CACTUS FAMILY (CACTACEAE) BASED ON EVIDENCE FROM TRNK/ MATK AND TRNL-TRNF SEQUENCES1 RETO NYFFELER2 Department of Organismic and Evolutionary Biology, Harvard University Herbaria, 22 Divinity Avenue, Cambridge, Massachusetts 02138 USA Cacti are a large and diverse group of stem succulents predominantly occurring in warm and arid North and South America. Chloroplast DNA sequences of the trnK intron, including the matK gene, were sequenced for 70 ingroup taxa and two outgroups from the Portulacaceae. In order to improve resolution in three major groups of Cactoideae, trnL-trnF sequences from members of these clades were added to a combined analysis. The three exemplars of Pereskia did not form a monophyletic group but a basal grade. The well-supported subfamilies Cactoideae and Opuntioideae and the genus Maihuenia formed a weakly supported clade sister to Pereskia. The parsimony analysis supported a sister group relationship of Maihuenia and Opuntioideae, although the likelihood analysis did not. Blossfeldia, a monotypic genus of morphologically modi®ed and ecologically specialized cacti, was identi®ed as the sister group to all other Cactoideae. -

Thorny Issues DATES & DETAILS —

FEBRUARY — 2012 ThornySACRAMENTO CACTUS & SUCCULENT Issues SOCIETY Volume 53, #2 Peru; Land of the Inca, Land of Cacti — February 27th, 7pm Inside this issue: This month we're going on a trip Mini Show—February 2 to Peru with our speaker, Mark Mini-Show Winners 2 Muradian. Starting in Chiclayo, and Dates & Details 3 ending in Cuzco, we will travel by bus to Calendar — MARCH 4 many habitats, sometimes on roads no bus should ever attempt to drive! Mark's video presentation, with all the sounds and motion helps us feel as if we are right there. With the fly over the Nazca lines and visit to Machu Picchu, this will be an exciting trip for us to take on a 'Rainy' Monday evening. Mark, also a fantastic potter, will bring a great selection of pots for us to Tephrocactus molinensis, purchase. So remember, bring some courtesy Elton Roberts extra money and/or your checkbook, especially since this is a great time to Sacramento Cactus & buy a unique pot to 'stage' your plant[s] for our Annual Show and Sale in Succulent Society May. —Sandy Waters, Program Chair Meetings are held the 4th Monday of each month at 7pm Location: Shepard Garden & Arts Center in Sacramento. 3330 McKinley Blvd Center’s phone number — 916/808-8800 No official meeting in December The public is warmly invited to attend meetings MINI SHOW — February, 2012 Cactus — Rebutia/Sulcorebutia Succulent — Sansevieria After the recent incorporation of the genera Aylostera, Sansevieria whose common names include: mother-in- Mediolobivia, Rebutia, Sulcorebutia, and Weingartia into law's tongue, devil's tongue, jinn's tongue, and snake the genus Rebutia, there are now around 60 species of plant, is a genus of about 70 species of flowering plants in cactus native to the eastern side of the Andes Mountains the family Ruscaceae, native to tropical and subtropical in Bolivia and Northern Argentina. -

ON the TAXONOMY of CACTACEAE JUSS by the EVIDENCE of SEED MICROMORPHOLOGY and SDS-PAGE ANALYSIS Lamiaa F

European Journal of Botany, Plant Sciences and Phytology Vol.2, No.3, pp.1-15, October 2015 ___Published by European Centre for Research Training and Development UK (www.eajournals.org) ON THE TAXONOMY OF CACTACEAE JUSS BY THE EVIDENCE OF SEED MICROMORPHOLOGY AND SDS-PAGE ANALYSIS Lamiaa F. Shalabi Department of Biological and Geological Sciences, Faculty of Education, Ain Shams University, Cairo, Egypt. Biology Department, Faculty of Sciences, Jazan University, Jazan, Saudi Arabia. ABSTRACT Numerical classification of 16 taxa of Cactaceae was studied using combination of micromorphological characters of seeds (using L.M and SEM) and SDS- PAGE analysis. Aspects of seed micromorphology and seed protein variation as defined were recorded and scored comparatively for the OTU's into a data matrix. Phenetic relationships of these taxa were established based on UPGMA-clustering method by using Jaccard coefficient of the NTSYS-pc 2.2 program. The results were compatible with the traditional relationships of some taxa as the split-off of Opuntia humifusa and Astrophytum myriostigma, at separate lines, these results are compatible with their placement in tribes Opuntieae (subfamily Opuntioideae) and Cacteae (Subfamily cactoideae) respectively, at the time, the placement of three taxa Pseudorhipsalis ramulosa, Rhipsalis baccifera Accession 1, and Rhipsalis baccifera Accession 2 together, the clustering of Hylocereus triangularis and Neobuxbaumia euphorbioides together at a unique tribe Phyllocacteae. The findings contradict in a number of cases the traditional studies, as the grouping of Trichocereus vasquezii with the two represents of genus Parodia despite of their placement in different tribes. KEYWORDS: Cactaceae, SDS-PAGE, Seed micromorpgology, SEM INTRODUCTION The Cactaceae are an exciting and problematic group of plants because of their varied morphology, succulence, and their showy flowers (Barthlott and Hunt 1993). -

Pollen Morphology of Cactaceae in Northern Chile

Gayana Bot. 72(2):72(2), 258-271,2015 2015 ISSN 0016-5301 Pollen morphology of Cactaceae in Northern Chile Morfología polínica de Cactáceas en el norte de Chile FLOREANA MIESEN1*, MARÍA EUGENIA DE PORRAS2 & ANTONIO MALDONADO2,3 1Department of Geography, Rheinische Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität Bonn, Meckenheimer Allee 166, 53115 Bonn, Germany. 2Centro de Estudios Avanzados en Zonas Áridas, Universidad de La Serena, Raúl Bitrán 1305, La Serena, Chile. 3Departamento de Biología Marina, Universidad Católica del Norte, Larrondo 1281, Coquimbo, Chile. *[email protected] ABSTRACT Chile is habitat to over 140 species of cactus of which 45% are endemic and most of them grow in the arid northernmost part of the country between 18°-32°S. As the Cactaceae family plants are quite well adapted to arid environments, their fossil pollen may serve as a tool to reconstruct past environmental dynamics as well as to trace some issues regarding the family evolution or even some autoecological aspects. Aiming to create a reference atlas to be applied to some of these purposes, the pollen morphology of the following 14 different species of the Cactaceae family from Northern Chile was studied under optical microscopy: Cumulopuntia sphaerica, Maihueniopsis camachoi, Tunilla soehrensii, Echinopsis atacamensis, Echinopsis coquimbana, Haageocereus chilensis, Oreocereus hempelianus, Oreocereus leucotrichus, Copiapoa coquimbana, Eriosyce aurata, Eriosyce subgibbosa, Eulychnia breviflora, Browningia candelaris and Corryocactus brevistylus. Pollen grains of species of the subfamily Opuntioideae are spheroidal, apolar and periporate whereas grains of the subfamily Cactoideae are subspheroidal, bipolar and tricolpate and can be taxonomically differentiated between tribes. The results show that it is possible to identify pollen from the Cactaceae family at the genus level but pollen taxonomic resolution may be complicated to identify up to a specific level. -

Prickly News 2017 November

P r i c k l y N e w s South Coast Cactus & Succulent Society Newsletter November 2017 Click here to visit our web site: PRESIDENT'S MESSAGE http://www.southcoastcss.org really enjoyed having Tom Glavitch visit Ius last month and learned a lot about Click here to visit cultivation of Euphorbias. A summary of his our Facebook page talk, included in this month’s Newsletter, shares many of his tips on growing Euphorbias including soil mix and how to NEXT MEETING handle the plants. I hope you find this as useful as I did. Ernesto Sandoval: "Propagation of Cacti It’s always interesting to hear the many variations on soil and Succulents" mix. I personally like to use more soil than pumice, but I am Sunday November 12, at 1:00 pm increasingly seeing some growers using mostly pumice in their (Program starts at 1:30pm) mix. For the inland growers, this means more frequent watering in the hot months. For those of us at the coast, the marine layer gives us a dose of daily moisture and a mostly pumice mix may REFRESHMENTS FOR NOVEMBER be advisable. Everyone has their own successful method and trial and error with some types of plants will prove the best for Thanks to those who helped in October: you. Carol Causey Jim Hanna For landscaping, another recommendation is the use of Isabel Cerda Carol Knight rocks. I recommend looking at this website for some ideas on Phyllis DeCrescenzo Ana MacKensie use of rocks in your succulent garden. https:// Art & Kitty Guzman Clif Wong southwestboulder.com/blog/7bestrockstopairwith Volunteers for November refreshments are: succulents. -

(Cactaceae Juss.) Species

Acta Agrobotanica DOI: 10.5586/aa.1697 ORIGINAL RESEARCH PAPER Publication history Received: 2016-05-24 Accepted: 2016-10-03 Anatomical and morphological features Published: 2016-12-20 of seedlings of some Cactoideae Eaton Handling editor Barbara Łotocka, Faculty of Agriculture and Biology, Warsaw (Cactaceae Juss.) species University of Life Sciences – SGGW, Poland Halyna Kalashnyk1*, Nataliia Nuzhyna2, Maryna Gaidarzhy2 Authors’ contributions 1 HK: carried out the experiments Department of Botany, Educational and Scientific Center “Institute of Biology and Medicine”, and wrote the manuscript; Taras Shevchenko National University of Kyiv, S. Petlyury 1, Kyiv 01032, Ukraine 2 NN: designed the anatomical Scientific laboratory “Introduced and natural phytodiversity”, Educational and Scientific Center experiment and contributed “Institute of Biology and Medicine”, Taras Shevchenko National University of Kyiv, S. Petlyury 1, to data interpretation; MG: Kyiv 01032, Ukraine designed the experiment, * Corresponding author. Email: [email protected] critically read the manuscript and contributed to data interpretation Abstract Funding Three-month-old seedlings of 11 species of the subfamily Cactoideae Melocac( - This study was financed from the research project tus bahiensis, Melocactus curvispinus, Echinopsis eyriesii, E. mirablis, E. peruviana, No. 14БП036-01 at the Taras Oreocereus celsianus, Rebutia flavistyla, Rebutia minuscula, Astrophytum myrios- Shevchenko National University tigma, Mamillaria columbiana, and M. prolifera) have been studied. These plants of Kyiv. exhibit a uniseriate epidermis, covered by a thin cuticle. Except for E. peruviana Competing interests and A. myriostigma, no hypodermis could be detected. The shoots of all studied No competing interests have specimens consist mainly of cortex parenchyma with large thin-walled cells. The been declared. -

Communique February 2006

COMMUNIQUE SAN GABRIEL VALLEY CACTUS & SUCCULENT SOCIETY An Affiliate of the Cactus & Succulent Society of America, Inc. Meetings are held at 7:30 PM on the 2nd Thursday of the month in the Lecture Hall, Los Angeles County Arboretum, Arcadia February 2006 Volume 39 Number 2 Monthly Meeting: Thursday, February 9th Join us for our regular meeting. Don’t forget to bring your Plant of the Month entries! Browse our collection of books in our Library. Buy a couple of raffle tickets. Talk with other members and enjoy our Mystery Presentation. _________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Plants of the Month: (see the attached write ups) CACTI – Weingartia and Sulcorebutia SUCCULENT – Sansevieria Bring your specimens in for our monthly mini-show. It will help you prepare for the real shows and give you an additional opportunity to show others your pride & joy. If you don’t have any of this type of plant you can learn about them at the meeting. Study Group: Join us on Wednesday, February 15, when our topic will be Photo and Digital. This is a don’t miss if you have a digital camera and are interested in taking pictures of your plants. As usual, the meeting will be held in the Grapevine room of the San Gabriel Adult Center, 324 South Mission Dr. (between the San Gabriel Mission and Civic Auditorium) at 7:30 pm. Also, we usually have a large selection of cuttings and other plants donated by members that are given away by lottery at the end of meeting. Anso Borrego Field Trip - Date Change: The Anso Borrego field trip is now scheduled for the week-end of April 22nd and 23rd. -

Plant Geography of Chile PLANT and VEGETATION

Plant Geography of Chile PLANT AND VEGETATION Volume 5 Series Editor: M.J.A. Werger For further volumes: http://www.springer.com/series/7549 Plant Geography of Chile by Andrés Moreira-Muñoz Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, Santiago, Chile 123 Dr. Andrés Moreira-Muñoz Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile Instituto de Geografia Av. Vicuña Mackenna 4860, Santiago Chile [email protected] ISSN 1875-1318 e-ISSN 1875-1326 ISBN 978-90-481-8747-8 e-ISBN 978-90-481-8748-5 DOI 10.1007/978-90-481-8748-5 Springer Dordrecht Heidelberg London New York © Springer Science+Business Media B.V. 2011 No part of this work may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, microfilming, recording or otherwise, without written permission from the Publisher, with the exception of any material supplied specifically for the purpose of being entered and executed on a computer system, for exclusive use by the purchaser of the work. ◦ ◦ Cover illustration: High-Andean vegetation at Laguna Miscanti (23 43 S, 67 47 W, 4350 m asl) Printed on acid-free paper Springer is part of Springer Science+Business Media (www.springer.com) Carlos Reiche (1860–1929) In Memoriam Foreword It is not just the brilliant and dramatic scenery that makes Chile such an attractive part of the world. No, that country has so very much more! And certainly it has a rich and beautiful flora. Chile’s plant world is strongly diversified and shows inter- esting geographical and evolutionary patterns. This is due to several factors: The geographical position of the country on the edge of a continental plate and stretch- ing along an extremely long latitudinal gradient from the tropics to the cold, barren rocks of Cape Horn, opposite Antarctica; the strong differences in altitude from sea level to the icy peaks of the Andes; the inclusion of distant islands in the country’s territory; the long geological and evolutionary history of the biota; and the mixture of tropical and temperate floras.