Do You Support Changes in Provincial Policy That Would Enable Nurse

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Financial Reporting and Is Ultimately Responsible for Reviewing and Approving the Financial Statements

Treasury Board Secretariat ANNUAL REPORT OF ONTARIO Financial Statements of Government Organizations VOLUME 2B | 2015-2016 7$%/( 2)&217(176 9ROXPH% 3DJH *HQHUDO 5HVSRQVLEOH0LQLVWU\IRU*RYHUQPHQW$JHQFLHV LL $*XLGHWRWKHAnnual Report .. LY ),1$1&,$/ 67$7(0(176 6HFWLRQ ņ*RYHUQPHQW 2UJDQL]DWLRQV± &RQW¶G 1LDJDUD3DUNV&RPPLVVLRQ 0DUFK 1RUWKHUQ2QWDULR+HULWDJH)XQG&RUSRUDWLRQ 0DUFK 2QWDULR$JHQF\IRU+HDOWK 3URWHFWLRQDQG 3URPRWLRQ 3XEOLF+HDOWK2QWDULR 0DUFK 2QWDULR&DSLWDO*URZWK&RUSRUDWLRQ 0DUFK 2QWDULR&OHDQ :DWHU$JHQF\ 'HFHPEHU 2QWDULR(GXFDWLRQDO&RPPXQLFDWLRQV$XWKRULW\ 79 2QWDULR 0DUFK 2QWDULR(OHFWULFLW\)LQDQFLDO&RUSRUDWLRQ 0DUFK 2QWDULR(QHUJ\%RDUG 0DUFK 2QWDULR)LQDQFLQJ$XWKRULW\ 0DUFK 2QWDULR)UHQFK/DQJXDJH(GXFDWLRQDO&RPPXQLFDWLRQV$XWKRULW\ 0DUFK 2QWDULR,PPLJUDQW,QYHVWRU&RUSRUDWLRQ 0DUFK 2QWDULR,QIUDVWUXFWXUH DQG/DQGV&RUSRUDWLRQ ,QIUDVWUXFWXUH 2QWDULR 0DUFK 2QWDULR0RUWJDJH DQG+RXVLQJ&RUSRUDWLRQ 0DUFK 2QWDULR1RUWKODQG7UDQVSRUWDWLRQ&RPPLVVLRQ 0DUFK 2QWDULR3ODFH&RUSRUDWLRQ 'HFHPEHU 2QWDULR5DFLQJ&RPPLVVLRQ 0DUFK 2QWDULR6HFXULWLHV&RPPLVVLRQ 0DUFK 2QWDULR7RXULVP0DUNHWLQJ3DUWQHUVKLS&RUSRUDWLRQ 0DUFK 2QWDULR7ULOOLXP)RXQGDWLRQ 0DUFK 2UQJH 0DUFK 2WWDZD&RQYHQWLRQ&HQWUH &RUSRUDWLRQ 0DUFK 3URYLQFH RI2QWDULR&RXQFLOIRUWKH$UWV 2QWDULR$UWV&RXQFLO 0DUFK 7KH 5R\DO2QWDULR0XVHXP 0DUFK 7RURQWR 2UJDQL]LQJ&RPPLWWHHIRUWKH 3DQ $PHULFDQ DQG3DUDSDQ$PHULFDQ*DPHV 7RURQWR 0DUFK 7RURQWR :DWHUIURQW5HYLWDOL]DWLRQ&RUSRUDWLRQ :DWHUIURQW7RURQWR 0DUFK L ANNUAL REPORT 5(63216,%/(0,1,675<)25*29(510(17%86,1(66(17(535,6(6 25*$1,=$7,216758676 0,6&(//$1(286),1$1&,$/67$7(0(176 -

Freedom Liberty

2013 ACCESS AND PRIVACY Office of the Information and Privacy Commissioner Ontario, Canada FREEDOM & LIBERTY 2013 STATISTICS In free and open societies, governments must be accessible and transparent to their citizens. TABLE OF CONTENTS Requests by the Public ...................................... 1 Provincial Compliance ..................................... 3 Municipal Compliance ................................... 12 Appeals .............................................................. 26 Privacy Complaints .......................................... 38 Personal Health Information Protection Act (PHIPA) .................................. 41 As I look back on the past years of the IPC, I feel that Ontarians can be assured that this office has grown into a first-class agency, known around the world for demonstrating innovation and leadership, in the fields of both access and privacy. STATISTICS 4 1 REQUESTS BY THE PUBLIC UNDER FIPPA/MFIPPA There were 55,760 freedom of information (FOI) requests filed across Ontario in 2013, nearly a 6% increase over 2012 where 52,831 were filed TOTAL FOI REQUESTS FILED BY JURISDICTION AND RECORDS TYPE Personal Information General Records Total Municipal 16,995 17,334 34,329 Provincial 7,029 14,402 21,431 Total 24,024 31,736 55,760 TOTAL FOI REQUESTS COMPLETED BY JURISDICTION AND RECORDS TYPE Personal Information General Records Total Municipal 16,726 17,304 34,030 Provincial 6,825 13,996 20,821 Total 23,551 31,300 54,851 TOTAL FOI REQUESTS COMPLETED BY SOURCE AND JURISDICTION Municipal Provincial Total -

Redesigning Care Through Digital Health Implementation

Redesigning Care through Digital Health Implementation Lessons Learned from Ontario Hospitals Acknowledgements The Ontario Hospital Association (OHA) would like to thank all the member hospitals and provincial partners who contributed to this resource. Individual contributing authors are noted at the end of each story. The OHA also acknowledges the ongoing and valuable work of all health care professionals who embrace change as hospitals innovate to improve care delivery and patient experiences. Disclaimer This publication is a collection of hospital submissions The Ontario Hospital Association (OHA) assumes no showcasing digital health implementation initiatives responsibility or liability for any harm, damage or other across the province. It has been created for general losses, direct or indirect, resulting from any reliance on information purposes only and implementation the use or the misuse of any information contained in suggestions should be adapted to the circumstances of this resource. Facts, figures and resources mentioned each hospital. Hospitals should seek their own legal and/ throughout the document have not been validated by or professional advice and opinion when developing the OHA. For details on sources of information, readers their organization’s approach and plans for digital health are encouraged to contact the hospital directly using the implementation. contact information cited in each submission. I Introduction Digital technologies have, and will continue to, These factors point to what may be the key ingredient -

ITAC Health PHIPA Modernization Feedback to ONTARIO MOHLTC FEBRUARY 21, 2020 Summary 2

ITAC Health PHIPA Modernization Feedback TO ONTARIO MOHLTC FEBRUARY 21, 2020 Summary 2 At the conclusion of November 20, 2019 meeting hosted by the MOHLTC privacy policy team that included representatives from ITAC Health Board and members, an action opportunity was requested and permission received to share the Ministry’s PHIPA Modernization document with select privacy subject matter experts within the ITAC Health membership. ITAC Health members, including SME members, have provided input that has been collected and summarized in this document. Our goal is to provide timely and in-depth feedback beyond the November meeting’s initial reflections on the PHIPA Modernization policies. We appreciate the opportunity to contribute to the Ministry our summary that includes five sections in companion to this executive summary: thematic topics related to PHIPA Modernization; beyond PHIPA, privacy (and security) contextual discussion; and general comments, recommendations and questions on PHIPA Modernization; direct references to slide content in Ministry’s PHIPHA Modernization deck; bibliography of external documents relevant to PHIPA Modernization effort 1. PHIPA Privacy Themes 3 Roles and responsibilities under the new PHIPA Penalties Under the New PHIPA Consent – aligned with GDPR Patient access to information De-identification and secondary use Right to portability Right to be forgotten Breach notification Research Ethic Boards harmonization Governance operating model Levers for change to enable data sharing Roles and responsibilities under the 4 new PHIPA Patient - a natural person whose personal data is processed by a controller or processor Health information custodian (HIC) - a person who determines the purposes for which and the manner in which any personal data are, or are to be, processed. -

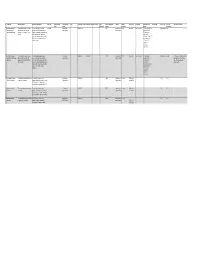

Copy of Data Inventory

Copy of Data Inventory # Public Title Short Description Long Description (Body) Other Title Data Custodian Data Custodian Tags Date Range ‐ Start Date Range ‐ End Date Created Date Contains Geographic Publisher Update Access Level Exemption Rationale not to Dataset URL License Type File Types Additional Comments Email Branch published Markers Frequency Release (extensions) 1 Consent and Capacity This dataset contains case‐related The case management system CaseLoad Consent and 2014‐03‐15 TRUE Consent and Daily Restricted Confidentiality The case management Other Licence DBF Board (CCB) Case data and information for CCB provides case‐related data such as Capacity Board Capacity Board system contains Management System applications from March 15 2014 contact information of the parties that private contact onward. come before the CCB, information information, about the hearing scheduling process, reference to personal file status, hearing information and health information case disposition. and sensitive, confidential party/case information. 2 Consent and Capacity This dataset contains case‐related The scheduling database provides Consent and 2006‐04‐01 2014‐03‐14 TRUE Consent and Other Restricted Confidentiality The scheduling Other Licence ACCDB This dataset is no longer updated. Board (CCB) Scheduling data and information for CCB case‐related data such as contact Capacity Board Capacity Board database contains Data not used for day‐to‐day Database applications from April 1 2006 to information of the parties that come private contact business. Occasional use for March 14 2014. before the CCB, information about the information, reference only. hearing scheduling process, file status, reference to personal hearing information and case health information disposition. and sensitive, confidential party/case information. -

Ontario's Electronic Health Record (EHR

Ontario’s Electronic Health Record (EHR) Conceptual Information Model (CIM) Digital Health Enabled VERSION 2.0 Version History Version Number Date Summary of Change Changed By 1.0 November 2014 Initial version part of Ontario’s Ehealth Blueprint eHealth Ontario, Architecture & Standards Division 2.0 June 26, 2019 Updated to align with HL7 Electronic Health Record eHealth Ontario, Architecture & System Functional Model (EHR-S FM) [Draft Standards Division Release 2.1] CIM 2.0 Page 1 Table of Contents Introduction ...................................................................................................................................................................... 3 Overview ............................................................................................................................................................................ 4 Information Architecture .................................................................................................................................................................................................... 6 EHR Information Principles ............................................................................................................................................................................................... 6 Modelling References .......................................................................................................................................................................................................... 7 Conceptual Information -

Exhibit 2 Crown-Controlled Corporations

Exhibit 2 Crown-Controlled Corporations Corporations whose accounts are audited by an auditor other than the Auditor General, with full access by the Auditor General to audit reports, working papers and other related documents as required Alcohol and Gaming Commission of Ontario North West Local Health Integration Network Agricultural Research Institute of Ontario Ontario Capital Growth Corporation Central East Local Health Integration Network Ontario College of Trades Central Local Health Integration Network Ontario French-language Educational Central West Local Health Integration Network Communications Authority (TFO) Champlain Local Health Intgration Network Ontario Health Quality Council Education Quality and Accountability Office Ontario Infrastructure and Lands Corporation eHealth Ontario (Infrastructure Ontario) Erie St. Clair Local Health Integration Network Ontario Lottery and Gaming Corporation Forest Renewal Trust Ontario Pension Board (Dec 31)* General Real Estate Portfolio Ontario Power Generation Inc. (Dec 31)* Hamilton Niagara Haldimand Brant Local Health Ontario Tourism Marketing Partnership Corporation Integration Network Ontario Trillium Foundation HealthForceOntario Marketing and Recruitment Ottawa Convention Centre Corporation Agency Owen Sound Transportation Company Limited Health Shared Services Ontario (HSSOntario) Ontario Agency for Health Protection and Higher Education Quality Council of Ontario Promotion (Public Health Ontario) Human Rights Legal Support Centre Royal Ontario Museum Hydro One Inc. (Dec 31)* Science -

Information Security and Privacy Policy IM-002 May 2018

Information Security and Privacy Policy IM-002 May 2018 1. Purpose: Patient Ombudsman will be collecting Sensitive Information that includes personal information (PI) and personal health information (PHI) in order to carry out its business functions described in the Excellent Care for All Act, 2010, S.O. 2010, c. 14 (ECFAA). This document sets out Patient Ombudsman’s policies regarding the management of information security and privacy protection. Information security refers to methodologies that protect information from unauthorized access, use, disclosure, disruption or destruction regardless of how the information is formatted or whether it is being processed or stored. Included in this document is the protection of privacy, managing security-related risks and limiting potential breach of privacy. The security of information and the protection of privacy is critical to the success of Patient Ombudsman to provide effective customer service and maintain public trust. Patient Ombudsman shall act as a responsible conservator of information assets entrusted to its care and shall promote a culture of information security and privacy. Loss of confidentiality, integrity, or availability of information and possible breach could adversely affect the achievement of Patient Ombudsman’s mandate and ability to store Sensitive Information. 2. Scope: This policy applies to all Employees of Patient Ombudsman. 3. Definitions: Business Owner: means any program director or equivalent having authority and accountability under legislation or policy for particular business activities and related business records. Employee: means a person employed by, or on contract with the Ontario Health Quality Council to work exclusively for Patient Ombudsman, and a person employed by or on contract to the Ontario Health Quality Council, operating as Health Quality Ontario, and assigned to provide Information Technology support to Patient Ombudsman. -

Download Brochure

Best Practices and Lessons Learned in Data Analytics for the Public Sector DATA ANALYTICS for the PUBLIC SECTOR SUMMIT Canada June 17-18, 2021 • Virtually everywhere North America’s Top Community for Big Data Innovation in the Public Sector. Join us for 2 days of Groundbreaking Content! Meet + Network + Learn From: Take Away Key Strategies To Utilize data analytics to make your organization more citizen-centric Create efficiencies using data, Amanda Carr Andre Loranger and improve service delivery CEO Assistant Chief Statistician Ontario Cannabis Store & Chief Data Officer Leverage data to influence Statistics Canada policy choices Transform your insights into actionable plans for better use of tax dollars James Capotosto Dorman Bazzle Build organizational support Chief Economist Chief Data Officer Government of Saskatchewan State of North Dakota for new digital initiatives Retrain your current workforce to “speak data,” and create a data-driven culture Harness open source data Vik Pant Tara Mulroney Chief Scientist and Vice President Technology Chief Science Advisor Edmonton International Airport Natural Resources Canada Gold Sponsor DataAnalyticsPublicSectorSummit.com Acquire Critical Insight From These Big Data Analytics Leaders: DATA ANALYTICS for the PUBLIC SECTOR SUMMIT Canada Welcome to the 2nd Annual Data Analytics for the Public Sector Summit. We are proud of our long history as the largest and most established big data community across the entire public sector. Immerse yourself in new ways of thinking as a big data leader within the public sector. Join us and experience a fast-paced deep dive into interactive discussions, intimate group chats and knowledge sharing. Generate innovative ideas with other leading public sector professionals who are passionate about sharing their perspective and expertise. -

The Consolidated Financial Statements

Treasury Board Secretariat Public Accounts of Ontario Please address your comments on this report to: Annual Report The Honourable Peter Bethlenfalvy President of the Treasury Board Room 4320, Fourth Floor, Whitney Block and Consolidated 99 Wellesley Street West, Toronto, Ontario M7A 1W3 Financial Statements You can also send your comments to the Minister by electronic mail 2018–2019 to: [email protected] To access this document online, visit Ontario.ca/publicaccounts © Queen’s Printer for Ontario, 2019 | ISSN 0381-2375 (Print) | ISSN 1913-5556 (Online) Treasury Board Secretariat Ministry of Finance Secrétariat du Conseil du Ministère des Finances Office of the Minister Office of the Minister Trésor Bureau du ministre Bureau du ministre 99 Wellesley Street West 7th Floor, Frost Building South 7 étage, Édifice Frost Sud Room 4320, Whitney Block 7 Queen’s Park Crescent 99, rue Wellesley Ouest 7 Queen’s Park Crescent Toronto, ON M7A 1W3 Toronto ON M7A 1Y7 Édifice Whitney, bureau 4320 Toronto ON M7A 1Y7 Tel.: 416-327-2333 Telephone: 416-325-0400 Toronto (Ontario) M7A 1W3 Téléphone: 416-325-0400 Fax: 416-327-3790 Facsimile: 416-325-0374 Tél. : 416 327-2333 Télécopieur:416-325-0374 Téléc. : 416 327-3790 The Honourable Elizabeth Dowdeswell, OC, OOnt Lieutenant Governor of Ontario Legislative Building Queen’s Park Toronto, ON M7A 1A1 May It Please Your Honour: The undersigned have the privilege to present the Public Accounts of the Province of Ontario for the fiscal year ended March 31, 2019, in accordance with the requirements of the Financial Administration Act. Respectfully submitted, Original signed by Original signed by The Honourable Peter Bethlenfalvy The Honourable Rod A. -

Ontario's Ehealth Strategy and Implications

ATHABASCA UNIVERSITY – CENTRE FOR INNOVATIVE MANAGEMENT Ontario’s eHealth Strategy AU MBA Applied Project APRJ-699 Ontario’s eHealth Strategy and Implications in Primary Care: Does the Strategy Have the Necessary Components to Succeed? Frances Murphy, Student No. 2500137 May 31, 2010 Applied Project Supervisor: Teresa Rose, PhD Word Count: 24,237 MurphyF-APRJ-Final 2 Table of Contents Abstract......................................................................................................................................................4 1.0Introduction ......................................................................................................................................6 1.1HealthcareExpenditures.........................................................................................................................7 1.2InformationTechnology:anEnablertoHealthOutcomesandEfficiency .............................9 1.3OntariosHealthcareITEnvironment.............................................................................................. 11 1.4TheRoleofPrimaryCareinOntariosHealthcareSystem....................................................... 12 1.5OntarioseHealthStrategy ................................................................................................................... 13 1.6WillOntarioseHealthStrategyBeSuccessfulInfluencingAdoptionofHealth InformationTechnologyinPrimaryCare?............................................................................................ 13 2.0ResearchPurpose,ResearchQuestionsandAssumptions........................................... -

Toward Better Accountability

Chapter 5 Toward Better Accountability Each year, our Annual Report addresses issues that provides a formal record of the relationship of accountability—and initiatives to help between the agency and the responsible minister. improve accountability—in government and It clarifies expectations and policies set out in the Chapter 5 across the broader public sector. This year, in statute that established the agency.) Most provin- addition to issues of accountability raised in cial agencies are required to produce annual reports our value-for-money audits, we have examined and submit them to their responsible minister the timeliness of provincial agencies in publicly within a specified time period. Ministers are then to reporting on their activities through their annual review these reports and make them public, either reports. Thorough and accurate disclosure of such by “tabling” them (officially presenting them) in information is essential to accountability, and is a the Legislature or by approving them for posting mandated requirement for provincial entities. As on an agency or government website. Although the this chapter highlights, there is considerable room intent of these requirements is to promote agency for improvement by some provincial agencies and transparency and accountability, we have found their responsible ministries in meeting the required that some aspects of a new directive issued by Man- timelines for reporting. agement Board of Cabinet in February 2015 instead conflict with this intent. We also noted: • Fewer than a quarter of agencies sampled had specific timeframes legislated for submitting 1.0 Main Points and/or tabling their annual reports. Despite the legislated requirement for their 2014 A provincial agency’s annual report, including annual reports, these timeframes were often its audited financial statements, provides details not met.