Trauma Team Activation for Geriatric Trauma at a Level II Trauma Center: Are the Elderly Under-Triaged?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Title: ED Trauma: Trauma Nurse Clinical Resuscitation

Title: ED Trauma: Trauma Nurse Clinical Resuscitation Document Category: Clinical Document Type: Policy Department/Committee Owner: Practice Council Original Date: Approved By (last review): Director of Emergency Services, Approval Date: 07/28/2014 Trauma Medical Director, Medical Director Emergency (Complete history at end of document.) Services POLICY: To provide immediate, effective and efficient patient care to the trauma patient, designated nursing staff will respond to the trauma room when a trauma page is received. TRAUMA CONTROL NURSE: 1) Role: a) The trauma control nurse (TCN) is a registered nurse (RN) with specialized training in the care of the traumatized patient, and who will function as the trauma team’s lead nurse. b) The TCN shall have successfully completed the Trauma Nurse Core Course (TNCC), Advanced Cardiac Life Support (ACLS), Emergency Nurse Pediatric Course (ENPC) or Pediatric Advanced Life Support (PALS), and role orientation with trauma services. c) Full-time employee or regularly scheduled part-time Emergency Department (ED) nurse. d) RN must have 6 months of LMH ED experience. 2) Trauma Control Duties: a) Inspects and stocks trauma room at beginning of each shift and after each trauma patient is discharged from the ED. b) Attempts to maintain trauma room temperature at 80-82 degrees Fahrenheit. c) Communicates with pre-hospital personnel to obtain patient information and prior field treatment and response. d) Makes determination that a patient meets Type I or Type II criteria and immediately notifies LMH’s Call System to initiate the Trauma Activation System. e) Assists physician with orders as directed. f) Acts as liaison with patient’s family/law enforcement/emergency medical services (EMS)/flight crews. -

Focus on Geriatric Trauma

European Journal of Trauma and Emergency Surgery (2019) 45:179–180 https://doi.org/10.1007/s00068-019-01107-3 EDITORIAL Focus on geriatric trauma Pol Maria Rommens1 Received: 15 February 2019 / Accepted: 26 February 2019 © Springer-Verlag GmbH Germany, part of Springer Nature 2019 Life expectancy is high and still growing in our societies. be minimal invasive; the implants use long bony corridors With higher age, the incidence of age-related diseases is for bridging or splinting. Conservative treatment is a valid increasing. Osteoporosis is a typical disease of the elderly, alternative in elderly patients with solitary lesions and low which is characterized by a decrease of bone mineral density. functional demands. Therefore, there is a higher risk of fractures due to low- Schmidt et al. [2] performed a logistic regression analysis energy trauma. The aged patient with a fracture is not com- on 1589 adult patients with isolated mild traumatic brain parable with an adolescent or adult with a musculoskeletal injury to assess the odds of any in-hospital adverse event by injury. Aged patients have a restricted physiological reserve age group, adjusted for gender and comorbidities. An expo- and do not afford long and invasive surgeries. In addition, nential increase of adverse events was observed after the age the strength of the fractured bone is lower. Consequently, of 75 years. Most important complications were urinary tract the prerequisites for fracture care are different. Conservative infection, delirium, respiratory complications and early com- management plays a more important role. However, surgical plications in trauma. These results demonstrate that geriat- treatment is obligatory in patients with unstable fractures ric trauma patients, who need surgical interventions, are at of the spine, pelvis, hip and lower extremities. -

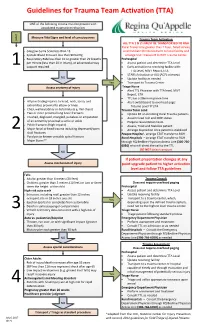

Guidelines for Trauma Team Activation (TTA)

Guidelines for Trauma Team Activation (TTA) ONE of the following criteria must be present with associated traumatic mechanism L e v e Measure Vital Signs and level of consciousness l Trauma Team Activation ALL TTA 1 & 2's MUST BE TRANSPORTED TO RGH Rural Travel time greater than 1 hour, failed airway · Glasgow Coma Scale less than 13 or immediate life threat divert to local facility and · Systolic Blood Pressure less than 90mmHg arrange STAT transport to RGH Trauma Center · Respiratory Rate less than 10 or greater then 29 breaths Prehospital per minute (less than 20 in infant), or advanced airway · Assess patient and determine TTA Level 1 support required · Early activation to receiving facility with: TTA Level, MIVT Report, ETA · STARS Activation or ALS (ACP) intercept NO · Update facility as needed Yes · Transport to Trauma Center Assess anatomy of injury Triage Nurse · Alert TTL Physician with TTA level, MIVT Report, ETA · TTL has a 20min response time · All penetrating injuries to head, neck, torso, and · Alert switchboard to overhead page: extremities proximal to elbow or knee Trauma Level ‘#’ ETA · Chest wall instability or deformity (e.g. flail chest) Trauma Team Lead · Two or more proximal long-bone fractures · Update ER on incoming Rural Trauma patients · Crushed, degloved, mangled, pulseless or amputation · Assume lead role and MRP status of an extremity proximal to wrist or ankle · Prepare resuscitation team · Pelvic fractures (high impact) · Assess, Treat and Stabilize patient 2 · Major facial or head trauma including depressed/open -

Evaluation and Management of Geriatric Trauma: an Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma Practice Management Guideline

GUIDELINE Evaluation and management of geriatric trauma: An Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma practice management guideline James Forrest Calland, MD, Angela M. Ingraham, MD, Niels Martin, MD, Gary T. Marshall, MD, Carl I. Schulman, MD, PhD, MSPH, Tristan Stapleton, and Robert D. Barraco, MD, MPH BACKGROUND: Aging patients constitute an increasing proportion of patients treated at trauma centers. Previous and existing guidelines addressing care of the injured elder have not adequately addressed emerging data regarding optimal means for undertaking triage decisions, correcting coagulopathy, and the limitations of supraphysiologic resuscitation. METHODS: More than 400 MEDLINE citations published between the years 2000 and 2008 were identified and screened. A total of 90 references were selected for the evidentiary table followed by consensus-based discussions regarding the level of evidence and the strength of recommendations that could be derived from the related findings of the individual studies. RESULTS: In general, a lower threshold for trauma activation should be used for injured patients aged 65 years or older who are evaluated at trauma centers. Furthermore, elderly patients with at least one body system with an AIS score of 3 or higher or a base deficit of j6or less should be treated at trauma centers, preferably in intensive care units staffed by surgeon-intensivists. In addition, all elderly patients who receive daily therapeutic anticoagulation should have appropriate assessment of their coagulation profile and cross- sectional imaging of the brain as soon as possible after admission where appropriate. In patients aged 65 years or older with a Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score less than 8, if substantial improvement in GCS is not realized within 72 hours of injury, consideration should be given to limiting further aggressive therapeutic interventions. -

Geriatric Trauma Care

Washington State Department of Health Office of Community Health Systems Emergency Medical Services & Trauma Section Trauma Clinical Guideline: Geriatric Trauma Care The Trauma Medical Directors and Program Managers Workgroup is an open forum for designated trauma services in Washington State to share ideas and concerns regarding the provision of trauma care. The workgroup meets regularly to encourage communication between services so that they may share information and improve quality of care. On occasion, at the request of the Emergency Medical Services and Trauma Care Steering Committee, the group discusses the value of specific clinical management guidelines for trauma care. This guideline is distributed by the Washington State Department of Health on behalf of the Emergency Medical Services and Trauma Care Steering Committee to assist trauma care services with developing their trauma patient care guidelines. The workgroup has categorized the type of guideline, the sponsoring organization, how it was developed, and whether it has been tested or validated. This information will assist physicians in evaluating the content of this guideline and its potential benefits for their practice and patients. The Department of Health does not mandate the use of this guideline. The department recognizes the varying resources of different services, and that approaches that work for one trauma service may not be suitable for others. The decision to use this guideline in any particular situation always depends on the independent medical judgment of the physician. We recommend that trauma services and physicians who choose to use this guideline consult with the department regularly for any updates to its content. The department appreciates receiving any information regarding practitioners’ experiences with this guideline. -

Management of Geriatric Trauma: General Overview Geriyatrik Travma Yönetimi: Genel Bakış

Anatolian Journal of Emergency Medicine 2019;2(4); 32-36 REVİEW / DERLEME Management of Geriatric Trauma: General Overview Geriyatrik Travma Yönetimi: Genel Bakış Abdullah Algın1 , Serkan Emre Eroğlu1 ÖZ ABSTRACT Türkiye İstatistik Kurumu (TÜİK) verilerine göre; 2012 According to the Turkish Statistical Institute (TSI), the yılında 5 milyon 682 bin olan yaşlı nüfus (65 yaş ve yukarı yaş) Turkish geriatric population (aged 65 and above) increased 2016 yılına kadarki süreçte %17,1 artarak 6 milyon 651 bin from 5,682,000 in 2012 to 6,651,000 in 2016. This represents olmuştur. Bu bilgiler ışığında, yaşlanmakta olan ülkemizde an increase of 17.1%. With respect to this information, daha fazla oranda geriatrik travma örnekleri ile geriatric trauma cases in Turkey are likely to increase over karşılaşacağımızı öngörebiliriz. Bu durum ise, travmaya genel the coming years. Though this is unlikely to transform yaklaşım açısından, diğer yaş gruplarıyla aralarında belirgin conventional medical approaches to trauma in geriatric fark yaratmasa da, azalmış fizyolojik rezerv, ikincil sorunlar patients, extra attention must be paid to this population’s ve olası gizli travmalar açısından dikkati gerektirir. Travma hidden trauma and complications secondary to reduced yönetiminin temellerinde yatan birincil ve ikincil bakıya ait physiological reserves. When applying the basic principles of kurallar aynen uygulanırken sergilenmesi gereken bu dikkat primary and secondary assessment in trauma management, gereksinimini ortaya çıkaran pek çok faktör vardır. myriad factors contribute to this need for additional caution Kullanılan ilaçlar, alerji öyküsü olup olmaması, eşlik eden when treating the elderly. bir kronik hastalıkların bilinmesi, bu hastaların yönetimi Medications, history of allergies, and the identification of sırasında gözönüne alınan faktörlerden sadece birkaçıdır. -

Anytown Trauma Center Trauma Protocols

ANYTOWN TRAUMA CENTER TRAUMA PROTOCOLS TITLE: TRAUMA TEAM ACTIVATION PROTOCOL PURPOSE: The purpose of the protocol is to establish guidelines for trauma team activation and define the members of the responding trauma team to facilitate the resuscitation and management of critical or seriously injured patients who require rapid, organized resuscitation, evaluation and stabilization to promote optimal outcomes. It also serves to provide triage guidelines for adult and pediatric patients. PROCESS: 1. TRAUMA TEAM ACTIVATION PROTCOL A. The criteria for activation of the trauma team is clearly defined and posted at the Emergency Department triage desk, by the EMS communication station and in the resuscitation rooms. B. The trauma team may be activated prior to arrival based on the EMS communication and their assessment. C. The trauma surgeon, emergency medicine physician, emergency department charge nurse/ house supervisor, emergency department nurses and the Trauma Program Manager may activate the trauma team. D. The person calling the trauma activation will initiate the trauma page to group page the trauma team and will specify the MOI, BP, HR, ETA and level of activation required and age if available. E. If the trauma team members are present in the emergency department and alert is still communicated to ensure everyone is notified. F. Trauma team member notification and arrival times will be documented on the trauma flow sheet (paper or electronic). G. Trauma team members will sign-in when they arrive. H. Trauma team members will be activated for all patients who meet the following criteria: 1. Level 1 trauma activation (major): life threatening injuries and/or unstable vital signs, limb-threating or disability threatening injury 2. -

Chapter 1 - Trauma Team from Prehospital Through the Emergency Department Test Questions

Chapter 1 - Trauma Team from Prehospital through the Emergency Department Test Questions 1. As the prehospital provider approaches the scene of a trauma call, they perform a. a radio transmission to the hospital b. a scene size up c. an estimate of neck size for c-collar d. an estimate of victim’s height and weight 2. Field intubation has been proven to improve outcome in a. patients with BP less than 90 mm Hg b. patients with GCS less than 9 c. patients with acute respiratory distress d. none of the above 3. A proven technique of hemorrhage control is a. Direct pressure b. Elevate above the heart c. Pressure points d. Cold application 4. Prehospital care for apparent pelvic fractures includes a. DO NOT ROCK or palpate the pelvis in the prehospital arena b. Avoid log rolling as much as possible c. Apply splint if in your area protocols d. All of the above 5. Most preventable deaths in trauma care are due to a. Delay in CPR b. Cardiac tamponade c. Airway obstruction d. Tension pneumothorax STN 2012 Electronic Library: Chapter 1 - Trauma Team from Prehospital Through the Emergency Department Test Questions 2 6. For resuscitation to occur, there must be a. Cellular perfusion and tissue oxygenation b. Restoration of a blood pressure greater than 90mm Hg c. A hemoglobin greater than 9g/dL d. A PaO2 greater than 80 mm Hg 7. The Trauma Triad of Death is a. Hypotension, tachycardia and decreased urine output b. Infection, inadequate nutrition, DVT’s c. Hypothermia, acidosis and coagulopathy d. -

Basic Trauma Overview - ABC

Basic Trauma Overview - ABC Dale Dangleben, MD, FACS 1 2 Team 3 Extended Team 4 Team Leader Decrease chaos / optimize care. – Remains calm – Maintains control and provides direction – Stays decisive – Sees the big picture (situational awareness) – Is open to other team members input – Directs resuscitation – Makes early decision to transfer the patients that exceed the local capabilities 5 Team Members − Know your roles in the trauma team − Remain calm − Be responsive to team leader −Voice suggestions or concerns 6 Responsibilities – Perform the Primary and secondary survey – Verbalize patient care – Report completed tasks 7 Responsibilities – Monitors the patient – Manual BP – Obtains IV access – Administers medications – Dresses wounds – Performs or assists in resuscitative procedures 8 Responsibilities Records data Ensures documentation accompanies patient upon transfer Assists team members as needed 9 Responsibilities – Obtains needed supplies – Coordinates communication with local and external resources – Assists team members as needed 10 Responsibilities • Place Oxygen on patient • Manage airway • Hold C spine • Manage ventilator if • Manage rapid infuser line patient intubated where indicated • Assists team members as needed 11 Organization of trauma resuscitation area – Basic adult and pediatric equipment for: • Airway management (cart) • IV access with warm fluids • Chest tube insertion • Hemorrhage control (tourniquets, pelvic binders) • Immobilization • Medications • Pediatric length/weight based tape (Broselow Tape) – Warming -

Addressing Traumatic Injury in Older Adults

2.6 HOURS Continuing Education By Christine L. Cutugno, PhD, RN THE ‘GRAYING’ OF TRAUMA CARE: ADDRESSING TRAUMATIC INJURY IN OLDER ADULTS Evidence-based strategies for managing trauma and its complications in this population. OVERVIEW: Trauma is the seventh leading cause of death in older adults. Factors that contribute to the higher rates of morbidity and mortality in geri- atric trauma victims include age-related physio- logic changes, a high prevalence of comorbidities, and poor physiologic reserves. Existing assessment and management standards for the care of older adults haven’t been evaluated for efficacy in geriat- ric trauma patients, and standardized protocols for trauma management haven’t been tested in older adults. Until such specific standards are developed, nurses must be guided by the relevant literature in various areas. The author reviews the mechanisms of traumatic injury in older adults, discusses the effects of aging and comorbidities, reviews assess- ment guidelines and prevention strategies for trauma-related complications, and outlines some evidence-based approaches for improving out- comes. An illustrative case is also provided. KEYWORDS: geriatric trauma, hospitalized older adults, older adults, trauma, traumatic injury Photo by Keith Brofsky. 40 AJN ▼ November 2011 ▼ Vol. 111, No. 11 ajnonline.com he “graying” of America is no secret; most of for hospitalized older adults. They are so common in us have heard some version of the statisti- this population that they’re becoming known as “geri- cal projections. In -

Pleural Effusion Following Rib Fractures in the Elderly

y olog & G nt er o ia r tr e i c G f R o e l s Journal of e a a n r r Mangram, et al., J Gerontol Geriatr Res 2016, 5:5 c u h o J Gerontology & Geriatric Research DOI: 10.4172/2167-7182.1000341 ISSN: 2167-7182 Research Article Open Access Pleural Effusion Following Rib Fractures in the Elderly: Are We Being Aggressive Enough? Alicia J Mangram1*, Nicolas Zhou1,2, Jacqueline Sohn1,2, Phillip Moeser1, Joseph F Sucher1, Alexzandra Hollingworth1, Francis R Ali-Osman1, Melissa Moyer1, Van A Johnson Jr1 and James K Dzandu1 1Honor Health John C. Lincoln Medical Center, USA 2Midwestern University-Arizona College of Osteopathic Medicine, USA *Corresponding author: Alicia J Mangram, Honor Health John C. Lincoln Medical Center, 250 E Dunlap Ave, Phoenix, AZ 85020, USA, Tel: 602-633-3721; Fax: 602-995-3795; E-mail: [email protected] Rec date: Apr 20, 2016; Acc date: Sep 06, 2016; Pub date: Sep 09, 2016 Copyright: © 2016 Mangram AJ, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. Abstract Background: Delayed pleural effusion (DPF) is an understudied complication of rib fractures. Many DPF are not treated unless symptomatic, however, the consequences of DPF in the elderly has not been discussed in current literature. We sought to investigate the characteristics of rib fracture DPF, its associated outcomes, and implications for management in geriatric trauma patients. -

Early Acute Management in Adults with Spinal Cord Injury: a Clinical Practice Guideline for Health-Care Professionals

SPINAL CORD MEDICINE EARLY ACUTE EARLY MANAGEMENT Early Acute Management in Adults with Spinal Cord Injury: A Clinical Practice Guideline for Health-Care Professionals Administrative and financial support provided by Paralyzed Veterans of America CLINICAL PRACTICE GUIDELINE: Consortium for Spinal Cord Medicine Member Organizations American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons American Academy of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation American Association of Neurological Surgeons American Association of Spinal Cord Injury Nurses American Association of Spinal Cord Injury Psychologists and Social Workers American College of Emergency Physicians American Congress of Rehabilitation Medicine American Occupational Therapy Association American Paraplegia Society American Physical Therapy Association American Psychological Association American Spinal Injury Association Association of Academic Physiatrists Association of Rehabilitation Nurses Christopher and Dana Reeve Foundation Congress of Neurological Surgeons Insurance Rehabilitation Study Group International Spinal Cord Society Paralyzed Veterans of America Society of Critical Care Medicine U. S. Department of Veterans Affairs United Spinal Association CLINICAL PRACTICE GUIDELINE Spinal Cord Medicine Early Acute Management in Adults with Spinal Cord Injury: A Clinical Practice Guideline for Health-Care Providers Consortium for Spinal Cord Medicine Administrative and financial support provided by Paralyzed Veterans of America © Copyright 2008, Paralyzed Veterans of America No copyright ownership